Chapter 9: Emotion and Affective Neuroscience

9.1: Affective Neuroscience: What is it?

Affect, in psychology, refers to the experience of emotions, moods, and feelings, so affective neuroscience examines how the brain creates emotional responses. Emotions are psychological phenomena that involve changes to the body (e.g., facial expression), changes in autonomic nervous system activity, feeling states (subjective responses), and urges to act in specific ways (motivations; Izard, 2010). Affective neuroscience aims to understand how matter (brain structures and chemicals) creates one of the most fascinating aspects of the mind—emotions. Affective neuroscience uses unbiased, observable measures that provide credible evidence to other scientists and laypersons on the importance of emotions. It also leads to biologically based treatments for affective disorders, such as depression and bipolar disorder.

The human brain and its emotional processes are complex and flexible. In order to study emotions in humans, human neuroscience must rely primarily on noninvasive techniques such as electroencephalography (EEG) and functional magnetic resonance imaging (fMRI) and on studies of individuals with brain lesions caused by accident or disease. Invasive neuroscience techniques, such as electrode implantation, lesioning, and hormone administration, are more powerful experimental tools but can only readily be used in nonhuman animals. While nonhuman animals possess simpler nervous systems and arguably more basic emotional responses than humans, affective circuits found in other species, particularly social mammals such as rats, dogs, and monkeys, function similarly to human affective networks. Thus, animal research serves as a valuable model for understanding affective processes in humans.

In humans, emotions and their associated neural systems have additional layers of complexity and flexibility. Compared to animals, humans experience a vast variety of nuanced and sometimes conflicting emotions. Humans also respond to these emotions in complex ways, such that conscious goals, values, and other cognitions influence behavior in addition to emotional responses. However, in this chapter, we focus on the similarities between organisms rather than the differences. We often use the term “organism” to refer to the individual who is experiencing an emotion or showing evidence of particular neural activations. An organism could be a rat, a monkey, or a human.

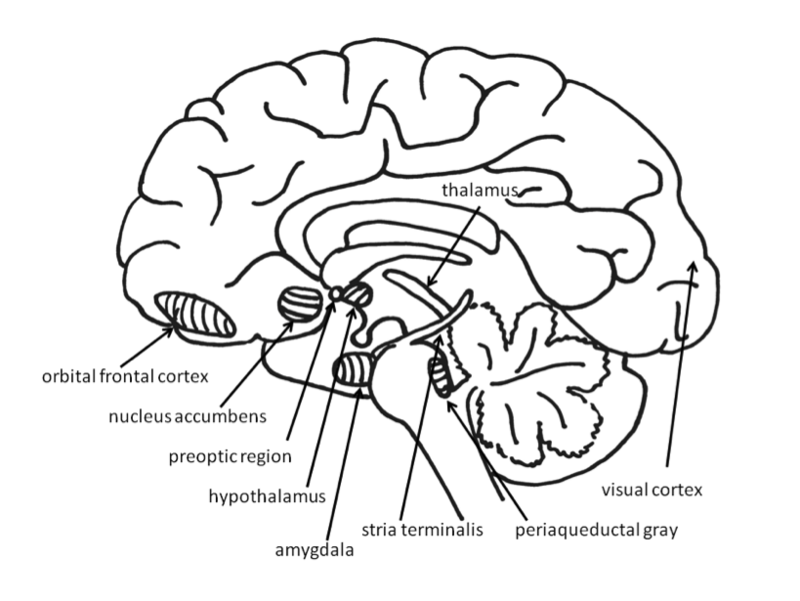

Across species, emotional responses are organized around the organism’s survival and reproductive needs. Emotions influence perception, cognition, and behavior to help organisms survive and thrive (Farb et al., 2013). Networks of structures in the brain respond to different needs, with some overlap between different emotions. Specific emotions are not located in a single structure of the brain. Instead, emotional responses involve networks of activation, with many parts of the brain activated during any emotional process. In fact, the brain circuits involved in emotional reactions include nearly the entire brain (Berridge & Kringelbach, 2013). Brain circuits located deep within the brain below the cerebral cortex are primarily responsible for generating basic emotions (Berridge & Kringelbach, 2013; Panksepp & Biven, 2012). In the past, research attention was focused on specific brain structures that will be reviewed here, but future research may find that additional areas of the brain are also important in these processes.

Media Attributions

- The cap © Flickr is licensed under a CC0 (Creative Commons Zero) license

- structure in the brain © Noba is licensed under a CC BY-NC-SA (Attribution NonCommercial ShareAlike) license

An emotional process that includes moods, subjective feelings, and discrete emotions.

The study of how the brain and nervous system process emotions