7.2 Levels of Socio-Cultural Integration

If cultures of various sizes and configurations are to be compared, there must be some common basis for defining political organization. In many small communities, the family unit functions as a political unit. As Julian Steward wrote about the Shoshone, a Native American group in the Nevada basin, “all features of the relatively simple culture were integrated and functioned on a family level. The family was the reproductive, economic, educational, political, and religious unit.”[1] In larger, more complex societies, however, the functions of the family are taken over by larger social institutions. The resources of the economy, for example, are managed by authority figures outside the family who demand taxes or other tribute. The educational function of the family may be taken over by schools constituted under the authority of a government, and the authority structure in the family is likely to be subsumed under the greater power of the state. Therefore, anthropologists need methods for assessing political organizations that can be applied to many different kinds of communities. This concept is called levels of socio-cultural integration.

Elman Service (1975) developed an influential scheme for categorizing the political character of societies that recognized four levels of socio-cultural integration: band, tribe, chiefdom, and state.[2] A band is the smallest unit of political organization, consisting of only a few families and no formal leadership positions. Tribes have larger populations but are organized around family ties and have fluid or shifting systems of temporary leadership. Chiefdoms are large political units in which the chief, who usually is determined by heredity, holds a formal position of power. States are the most complex form of political organization and are characterized by a central government that has a monopoly over legitimate uses of physical force, a sizable bureaucracy, a system of formal laws, and a standing military force.

Each type of political integration can be further categorized as egalitarian, ranked, or stratified. Band societies and tribal societies generally are considered egalitarian—there is no great difference in status or power between individuals, and there are as many valued status positions in the societies as there are persons able to fill them. Chiefdoms are ranked societies; there are substantial differences in the wealth and social status of individuals based on how closely related they are to the chief. In ranked societies, there are a limited number of positions of power or status, and only a few can occupy them. State societies are stratified. There are large differences in the wealth, status, and power of individuals based on unequal access to resources and positions of power. Socio-economic classes, for instance, are forms of stratification in many state societies.[3]

Quick Reading Check: Take one form of socio-cultural political organization – band, tribe, chiefdom, and state – and discuss how it functions including use of power and authority (defined earlier in reading) as well as their levels of (in)equity.

7.2.1 Egalitarian Societies

We humans are not equal in all things. Both gender and age along with other social identity markers have determined the amount of power and status people have within societies. The status of women is low relative to the status of men in many, if not most, societies, as we will see. In some societies, the aged enjoy greater prestige than the young; in others, the aged are subjected to discrimination in employment and other areas. Even in Japan, which has traditionally been known for its respect for elders, the prestige of the aged is in decline. Also, humans vary in terms of our abilities. Some are more eloquent or skilled technically than others; some are expert craft persons while others are not; some excel at conceptual thought, whereas for the rest of us, there is always the For Dummies book series to manage our computers, software, and other parts of our daily lives such as wine and sex.

In a complex society, it may seem that social classes—differences in wealth and status—are, like death and taxes, inevitable: that one is born into wealth, poverty, or somewhere in between and has no say in the matter, at least at the start of life, and that social class is an involuntary position in society that cannot be questioned or changed. But is this true? Is the concept of social class universal, ie. seen in every society across the world? Well, let’s look at the data found in ethnographic research. We find that among foragers, there is no advantage to hoarding food; in most climates, it will rot before one’s eyes. Nor is there much personal property and leadership. Where it exists, it is informal. In forager societies, the basic ingredients for social class do not exist. Foragers such as the !Kung, Inuit, and aboriginal Australians, are egalitarian societies in which there are few differences between members in wealth, status, and power. Highly skilled and less skilled hunters do not belong to different strata in the way that the captains of industry do from you and me. The less skilled hunters in egalitarian societies receive a share of the meat and have the right to be heard on important decisions. Egalitarian societies also lack a government or centralized leadership. Their leaders, known as headmen or big men, emerge by consensus of the group. Foraging societies are always egalitarian, but so are many societies that practice horticulture or pastoralism. In terms of political organization, egalitarian societies can be either bands or tribes.

Quick Reading Check: How do egalitarian societies deal with wealth?

7.2.2 Band-Level Political Organization

Societies organized as a band typically comprise foragers who rely on hunting and gathering and are therefore nomadic, are few in number (rarely exceeding 100 persons), and form small groups consisting of a few families and a shifting population. Bands lack formal leadership. Richard Lee went so far as to say that the Dobe! Kung had no leaders. To quote one of his informants, “Of course we have headmen. Each one of us is headman over himself.”[4] At most, a band’s leader is primus inter pares or “first among equals” assuming anyone is first at all. Modesty is a valued trait; arrogance and competitiveness are not acceptable in societies characterized by reverse dominance. What leadership there is in band societies tends to be transient and subject to shifting circumstances. For example, among the Paiute in North America, “rabbit bosses” coordinated rabbit drives during the hunting season but played no leadership role otherwise. Some “leaders” are excellent mediators who are called on when individuals are involved in disputes while others are perceived as skilled shamans or future-seers who are consulted periodically. There are no formal offices or rules of succession.[5]

Bands were probably the first political unit to come into existence outside the family itself. There is some debate in anthropology about how the earliest bands were organized. Elman Service argued that patrilocal bands organized around groups of related men served as the prototype, reasoning that groups centered on male family relationships made sense because male cooperation was essential to hunting.[6] M. Kay Martin and Barbara Voorhies pointed out in rebuttal that gathering vegetable foods, which typically was viewed as women’s work, actually contributed a greater number of calories in most cultures and thus that matrilocal bands organized around groups of related women would be closer to the norm.[7] Indeed, in societies in which hunting is the primary source of food, such as the Inuit, women tend to be subordinate to men while men and women tend to have roughly equal status in societies that mainly gather plants for food.

Quick Reading Check

7.2.3 Law, Disputes and Warfare in Band Societies

Within bands of people, disputes are typically resolved informally and in social ways. There are no formal mediators or any organizational equivalent of a court of law. A good mediator may emerge—or may not. In some cultures, duels are employed. Among the Inuit, for example, disputants engage in a duel using songs in which, drum in hand, they chant insults at each other before an audience. The audience selects the better chanter and thereby the winner in the dispute.[8] The Mbuti of the African Congo, on the other hand, use ridicule; even children berate adults for laziness, quarreling, or selfishness. If ridicule fails, the Mbuti elders evaluate the dispute carefully, determine the cause, and, in extreme cases, walk to the center of the camp and criticize the individuals by name, using humor to soften their criticism—the group, after all, must get along.[9]

Nevertheless, conflict does sometimes break out into war between bands and, sometimes, within them. Such warfare is usually sporadic and short-lived since bands do not have formal leadership structures or enough warriors to sustain conflict for long. Most of the conflict arises from interpersonal arguments. Among the Tiwi of Australia, for example, failure of one band to reciprocate another band’s wife-giving with one of its own female relatives led to abduction of women by the aggrieved band, precipitating a “war” that involved some spear-throwing (many did not shoot straight and even some of the onlookers were wounded) but mostly violent talk and verbal abuse.[10] For the Dobe !Kung, Lee found 22 cases of homicide by males and other periodic episodes of violence, mostly in disputes over women—not quite the gentle souls Elizabeth Marshall Thomas depicted in her Harmless People (1959).[11]

Quick Reading Check: Describe two different ways in which conflicts can be settled in Band Societies.

7.2.4 Tribal Political Organization

Whereas bands involve small populations without structure, tribal societies involve at least two well- defined groups linked together in some way and range in population from about 100 to as many as 5,000 people. Though their social institutions can be fairly complex, there are no centralized political structures or offices in the strict sense of those terms. There may be headmen, but there are no rules of succession and sons do not necessarily succeed their fathers as is the case with chiefdoms. Tribal leadership roles are open to anyone—in practice, usually men, especially elder men who acquire leadership positions because of their personal abilities and qualities. Leaders in tribes do not have a means of coercing others or formal powers associated with their positions. Instead, they must persuade others to take actions they feel are needed. A Yanomami headsman, for instance, said that he would never issue an order unless he knew it would be obeyed. The headman Kaobawä exercised influence by example and by making suggestions and warning of the consequences of taking or not taking an action.[12]

Like bands, tribes are egalitarian societies. Some individuals in a tribe do sometimes accumulate personal property but not to the extent that other tribe members are deprived. And every (almost always male) person has the opportunity to become a headman or leader and, like bands, one’s leadership position can be situational. One man may be a good mediator, another an exemplary warrior, and a third capable of leading a hunt or finding a more ideal area for cultivation or grazing herds. An example illustrating this kind of leadership is the big man of New Guinea; the term is derived from the languages of New Guinean tribes (literally meaning “man of influence”). The big man is one who has acquired followers by doing favors they cannot possibly repay, such as settling their debts or providing bride-wealth. He might also acquire as many wives as possible to create alliances with his wives’ families. His wives could work to care for as many pigs as possible, for example, and in due course, he could sponsor a pig feast that would serve to put more tribe members in his debt and shame his rivals. It is worth noting that the followers, incapable of repaying the Big Man’s gifts, stand metaphorically as beggars to him.[13]

Still, a big man does not have the power of a monarch. His role is not hereditary. His son must demonstrate his worth and acquire his own following—he must become a big man in his own right. Furthermore, there usually are other big men in the village who are his potential rivals. Another man who proves himself capable of acquiring a following can displace the existing big man. The big man also has no power to coerce—no army or police force. He cannot prevent a follower from joining another big man, nor can he force the follower to pay any debt owed. There is no New Guinean equivalent of a U.S. marshal. Therefore, he can have his way only by diplomacy and persuasion—which do not always work.[14]

Quick Reading Check: How are tribes and bands alike? How are they different?

7.2.5 Tribal Systems of Social Integration

Tribal societies have much larger populations than bands and thus must have mechanisms for creating and maintaining connections between tribe members. The family ties that unite members of a band are not sufficient to maintain solidarity and cohesion in the larger population of a tribe. Some of the systems that knit tribes together are based on family (kin) relationships, including various kinds of marriage and family lineage systems, but there are also ways to foster tribal solidarity outside of family arrangements through systems that unite members of a tribe by age or gender.

Integration through Age Grades and Age Sets

Tribes use various systems to encourage solidarity or feelings of connectedness between people who are not related by family ties. These systems, sometimes known as sodalities, unite people across family groups. In one sense, all societies are divided into age categories. In the U.S. educational system, for instance, children are matched to grades in school according to their age—six-year-olds in first grade and thirteen-year-olds in eighth grade. Other cultures, however, have established complex age-based social structures. Many pastoralists in East Africa, for example, have age grades and age sets. Age sets are named categories to which men of a certain age are assigned at birth. Age grades are groups of men who are close to one another in age and share similar duties or responsibilities. All men cycle through each age grade over the course of their lifetimes. As the age sets advance, the men assume the duties associated with each age grade.

An example of this kind of tribal society is the Tiriki of Kenya. From birth to about fifteen years of age, boys become members of one of seven named age sets. When the last boy is recruited, that age set closes and a new one opens. For example, young and adult males who belonged to the “Juma” age set in 1939 became warriors by 1954. The “Mayima” were already warriors in 1939 and became elder warriors during that period. In precolonial times, men of the warrior age grade defended the herds of the Tiriki and conducted raids on other tribes while the elder warriors acquired cattle and houses and took on wives. There were recurring reports of husbands who were much older than their wives, who had married early in life, often as young as fifteen or sixteen. As solid citizens of the Tiriki, the elder warriors also handled decision-making functions of the tribe as a whole; their legislation affected the entire village while also representing their own kin groups. The other age sets also moved up through age grades in the fifteen-year period. The elder warriors in 1939, “Nyonje,” became the judicial elders by 1954. Their function was to resolve disputes that arose between individuals, families, and kin groups, of which some elders were a part. The “Jiminigayi,” judicial elders in 1939, became ritual elders in 1954, handling supernatural functions that involved the entire Tiriki community. During this period, the open age set was “Kabalach.” Its prior members had all grown old or died by 1939 and new boys joined it between 1939 and 1954. Thus, the Tiriki age sets moved in continuous 105-year cycles. This age grade and age set system encourages bonds between men of similar ages. Their loyalty to their families is tempered by their responsibilities to their fellows of the same age.[15]

| Traditional Duties of Age Grade | Age Sets 1939 | Age Sets 1954 | Age Sets 1979 | Age Sets 1994 |

| Retired or Deceased: 91-105 | Kabalach | Golongolo | Jiminigayi | Nyonje |

| Ritual Elders: 76-90 | Golongolo | Jiminigayi | Nyonje | Mayina |

| Judicial Elders: 61-750 | Jiminigayi | Nyonje | Mayina | Juma |

| Elder Warriors: 46-60 | Nyonje | Mayina | Juma | Sawe |

| Warriors: 31-45 | Mayina | Juma | Sawe | Kabalach |

| Initiated and Uninitiated Youths: 16-30 | Juma | Sawe | Kabalach | Golongolo |

| Small Boys: 0-15 | Sawe | Kabalach | Golongolo | Jiminigayi |

Quick Reading Check: What questions do you have about Figure 1 and the example of age sets and age grades from the Tiriki?

Integration Through Bachelor Associations and Men’s Houses

Among most, if not all, tribes of New Guinea, the existence of men’s houses serves to cut across family lineage groups in a village. Perhaps the most fastidious case of male association in New Guinea is the bachelor association of the Mae-Enga, who live in the northern highlands. In their culture, a boy becomes conscious of the distance between males and females before he leaves home at age five to live in the men’s house. Women are regarded as potentially unclean, and strict codes that minimize male- female relations are enforced. Sanggai festivals reinforce this division. During the festival, every youth of age 15 or 16 goes into seclusion in the forest and observes additional restrictions, such as avoiding pigs (which are cared for by women) and avoiding gazing at the ground lest he see female footprints or pig feces.[16] One can see, therefore, that every boy commits his loyalty to the men’s house early in life even though he remains a member of his birth family. Men’s houses are the center of male activities. There, they draw up strategies for warfare, conduct ritual activities involving magic and honoring of ancestral spirits, and plan and rehearse periodic pig feasts.

Integration through Gifts and Feasting

Exchanges and the informal obligations associated with them are primary devices by which bands and tribes maintain a degree of order and forestall armed conflict, which was viewed as the “state of nature” for tribal societies by Locke and Hobbes, in the absence of exercises of force by police or an army. Marcel Mauss, nephew and student of eminent French sociologist Emile Durkheim, attempted in 1925 to explain gift giving and its attendant obligations cross-culturally in his book, The Gift: Forms and Functions of Exchange in Archaic Societies. He started with the assumption that two groups have an imperative to establish a relationship of some kind. There are three options when they meet for the first time. They could pass each other by and never see each other again. They may resort to arms with an uncertain outcome. One could wipe the other out or, more likely, win at great cost of men and property or fight to a draw. The third option is to “come to terms” with each other by establishing a more or less permanent relationship.[17] Exchanging gifts is one way for groups to establish this relationship.

These gift exchanges are quite different from Western ideas about gifts. In societies that lack a central government, formal law enforcement powers, and collection agents, the gift exchanges are obligatory and have the force of law in the absence of law. Mauss referred to them as “total prestations.” Though no Dun and Bradstreet agents would come to collect, the potential for conflict that could break out at any time reinforced the obligations.[18] According to Mauss, the first obligation is to give; it must be met if a group is to extend social ties to others. The second obligation is to receive; refusal of a gift constitutes rejection of the offer of friendship as well. Conflicts can arise from the perceived insult of a rejected offer. The third obligation is to repay. One who fails to make a gift in return will be seen as in debt—in essence, a beggar. Mauss offered several ethnographic cases that illustrated these obligations. Every gift conferred power to the giver, expressed by the Polynesian terms mana (an intangible supernatural force) and hau (among the Maori, the “spirit of the gift,” which must be returned to its owner).[19] Marriage and its associated obligations also can be viewed as a form of gift-giving as one family “gives” a bride or groom to the other.

Integration through Marriage

Most tribal societies’ political organizations involve marriage, which is a logical vehicle for creating alliances between groups. One of the most well-documented types of marriage alliance is bilateral cross-cousin marriage in which a man marries his cross-cousin—one he is related to through two links, his father’s sister and his mother’s brother. These marriages have been documented among the Yanomami, an indigenous group living in Venezuela and Brazil. Yanomami villages are typically populated by two or more extended family groups also known as lineages. Disputes and disagreements are bound to occur, and these tensions can potentially escalate to open conflict or even physical violence. Bilateral cross-cousin marriage provides a means of linking lineage groups together over time through the exchange of brides. Because cross-cousin marriage links people together by both marriage and blood ties (kinship), these unions can reduce tension between the groups or at least provide an incentive for members of rival lineages to work together.

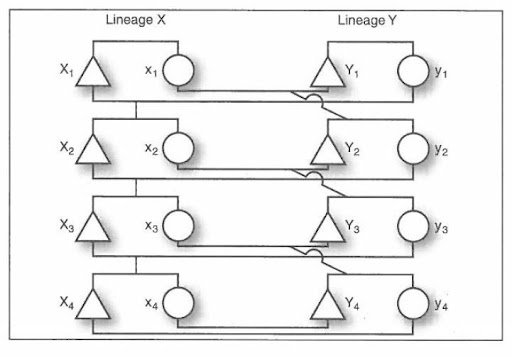

To get a more detailed picture of how marriages integrate family groups, consider the following family diagrams. In these diagrams, triangles represent males and circles represent females. Vertical lines represent a generational link connecting, say, a man to his father. Horizontal lines above two figures are sibling links; thus, a triangle connected to a circle by a horizontal line represents a brother and sister. Equal signs connect husbands and wives. In some diagrams in which use of an equal sign is not realistic, a horizontal line drawn below the two figures shows their marriage link.

Figure 7.3 depicts the alliance created by the bilateral cross-cousin marriage system. In this figure, uppercase letters represent males and lowercase letters represent females, Thus, X refers to all of the males of Lineage X and Y refers to all of the males of Lineage Y; likewise, x refers to all of the females of Lineage X and y refers to all of the females of Lineage Y.

Consider the third generation in the diagram. X3 has married y3 (the horizontal line below the fig- ures), creating an affinal link. Trace the relationship between X3 and y3 through their matrilateral links—the links between a mother and her brother. You can see from the diagram that X3’s mother is x2 and her brother is Y2 and his daughter is y3. Therefore, y3 is X3’s mother’s brother’s daughter.

Now trace the patrilateral links of this couple—the links between a father and his sister. X3’s father is X2 and X2’s sister is x2, who married Y2, which makes her daughter y3—his father’s sister’s daughter. Work your way through the description and diagram until you are comfortable understanding the connections.

Now do the same thing with Y3 by tracing his matrilateral ties with his wife x3. His mother is x2 and her brother is X2, which makes his mother’s brother’s daughter x3. On the patrilateral side, his father is Y2, and Y2’s sister is y2, who is married to X2 Therefore, their daughter is x3.

This example represents the ideal bilateral cross-cousin marriage: a man marries a woman who is both his mother’s brother’s daughter and his father’s sister’s daughter. The man’s matrilateral cross- cousin and patrilateral cross-cousin are the same woman! Thus, the two lineages have discharged their obligations to one another in the same generation. Lineage X provides a daughter to lineage Y and lineage Y reciprocates with a daughter. Each of the lineages therefore retains its potential to reproduce in the next generation. The obligation incurred by lineage Y from taking lineage X’s daughter in marriage has been repaid by giving a daughter in marriage to lineage X.

This type of marriage is what Robin Fox, following Claude Levi-Strauss, called restricted exchange.[20] Notice that only two extended families can engage in this exchange. Society remains relatively simple because it can expand only by splitting off. And, as we will see later, when daughter villages split off, the two lineages move together. Not all marriages can conform to this type of exchange. Often, the patrilateral cross-cousin is not the same person; there may be two or more persons. Furthermore, in some situations, a man can marry either a matrilateral or a patrilateral cross-cousin but not both. The example of the ideal type of cross- cousin marriage is used to demonstrate the logical outcome of such unions.

Quick Reading Check: How does (tribal) integration by marriage work? Ie, how can marriage create beneficial alliances?

Integration Through a Segmentary Lineage

Another type of kin-based integrative mechanism is a segmentary lineage. As previously noted, a lineage is a group of people who can trace or demonstrate their descent from a founding ancestor through a line of males or a line of females. A segmentary lineage is a hierarchy of lineages that contains both close and relatively distant family members. At the base are several minimal lineages whose members trace their descent from their founder back two or three generations. At the top is the founder of all of the lineages, and two or more maximal lineages can derive from the founder’s lineage. Between the maximal and the minimal lineages are several intermediate lineages. For purposes of simplicity, we will discuss only the maximal and minimal lineages.

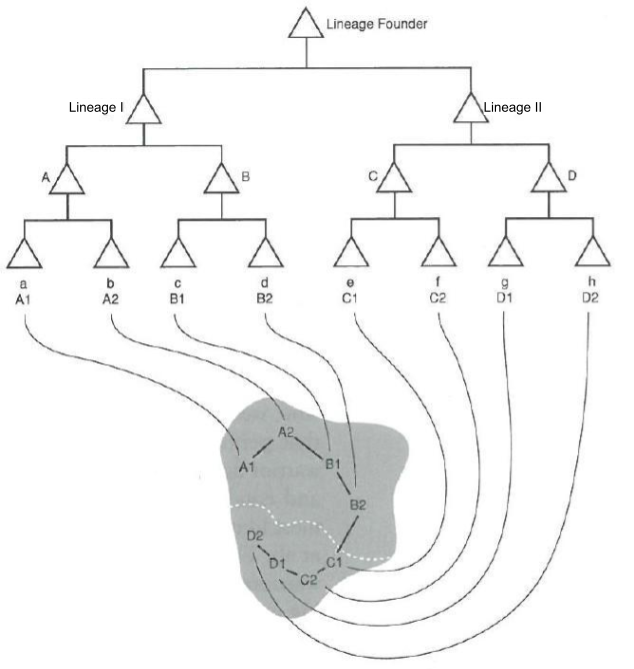

One characteristic of segmentary lineages is complementary opposition. To illustrate, consider the chart in Figure 3, which presents two maximal lineages, A and B, each having two minimal lineages: A1 and A2 for A and B1 and B2 for B.

Suppose A1 starts a feud with A2 over cattle theft. Since A1 and A2 are of the same maximal lineage, their feud is likely to be contained within that lineage, and B1 and B2 are likely to ignore the conflict since it is no concern of theirs. Now suppose A2 attacks B1 for cattle theft. In that case, A1 might unite with A2 to feud with B1, who B2 join in to defend. Thus, the feud would involve everyone in maximal lineage A against everyone in maximal lineage B. Finally, consider an attack by an outside tribe against A1. In response, both maximal lineages might rise up and defend A1.

The classic examples of segmentary lineages were described by E. E. Evans-Pritchard (1940) in his discussion of the Nuer, pastoralists who lived in southern Sudan.[21] Paul Bohannan (1989) also described this system among the Tiv, who were West African pastoralists, and Robert Murphy and Leonard Kasdan (1959) analyzed the importance of these lineages among the Bedouin of the Middle East.[22] Segmentary lineages often develop in environments in which a tribal society is surrounded by several other tribal societies. Hostility between the tribes induces their members to retain ties with their kin and to mobilize them when external conflicts arise. An example of this is ties maintained between the Nuer and the Dinka. Once a conflict is over, segmentary lineages typically dissolve into their constituent units. Another attribute of segmentary lineages is local genealogical segmentation, meaning close lineages dwell near each other, providing a physical reminder of their genealogy.[23] A Bedouin proverb summarizes the philosophy behind segmentary lineages:

I against my brother

I and my brother against my cousin

I, my brother, and my cousin against the world

Segmentary lineages regulate both warfare and inheritance and property rights. As noted by Sahlins (1961) in studies of the Nuer, tribes in which such lineages occur typically have relatively large populations of close to 100,000 persons.[24]

Quick Reading Check: Provide an example of how segmentary lineage works.

7.2.6 Law in Tribal Societies

Has anyone seen the movie Wedding Crashers? The main characters are divorced mediators. I always think about this when trying to wrap my mind about how “mediation” can resolve conflicts in our society? What could we learn from the Leopard Skin Chief system?

Tribal societies generally lack systems of codified law whereby damages, crimes, remedies, and punishments are specified. Only state-level political systems can determine, usually by writing formal laws, which behaviors are permissible and which are not (discussed later in this chapter). In tribes, there are no systems of law enforcement whereby an agency such as the police, the sheriff, or an army can enforce laws enacted by an appropriate authority. And, as already noted, headmen and big men cannot force their will on others.

In tribal societies, as in all societies, conflicts arise between individuals. Sometimes the issues are equivalent to crimes—taking of property or commision of violence—that are not considered legitimate in a given society. Other issues are civil disagreements—questions of ownership, damage to property, an accidental death. In tribal societies, the aim is not so much to determine guilt or innocence or to assign criminal or civil responsibility as it is to resolve conflict, which can be accomplished in various ways. The parties might choose to avoid each other. Bands, tribes, and kin groups often move away from each other geographically, which is much easier for them to do than for people living in complex societies.

One issue in tribal societies, as in all societies, is guilt or innocence. When no one witnesses an offense or an account is deemed unreliable, tribal societies sometimes rely on the supernatural. Oaths, for example, involve calling on a deity to bear witness to the truth of what one says; the oath given in court is a holdover from this practice. An ordeal is used to determine guilt or innocence by submitting the accused to dangerous, painful, or risky tests believed to be controlled by supernatural forces. The poison oracle used by the Azande of the Sudan and the Congo is an ordeal based on their belief that most misfortunes are induced by witchcraft (in this case, witchcraft refers to ill feeling of one person toward another). A chicken is force fed a strychnine concoction known as benge just as the name of the suspect is called out. If the chicken dies, the suspect is deemed guilty and is punished or goes through reconciliation.[25]

A more commonly exercised option is to find ways to resolve the dispute. In small groups, an unre- solved question can quickly escalate to violence and disrupt the group. The first step is often negotiation; the parties attempt to resolve the conflict by direct discussion in hope of arriving at an agreement. Offenders sometimes make a ritual apology, particularly if they are sensitive to community opinion. In Fiji, for example, offenders make ceremonial apologies called i soro, one of the meanings of which is “I surrender.” An intermediary speaks, offers a token gift to the offended party, and asks for forgiveness, and the request is rarely rejected.[26]

When negotiation or a ritual apology fails, often the next step is to recruit a third party to mediate a settlement as there is no official who has the power to enforce a settlement. A classic example in the anthropological literature is the Leopard Skin Chief among the Nuer, who is identified by a leopard skin wrap around his shoulders. He is not a chief but is a mediator. The position is hereditary, has religious overtones, and is responsible for the social well-being of the tribal segment. He typically is called on for serious matters such as murder. The culprit immediately goes to the residence of the Leopard Skin Chief, who cuts the culprit’s arm until blood flows. If the culprit fears vengeance by the dead man’s family, he remains at the residence, which is considered a sanctuary, and the Leopard Skin Chief then acts as a go-between for the families of the perpetrator and the dead man.

The Leopard Skin Chief cannot force the parties to settle and cannot enforce any settlement they reach. The source of his influence is the desire for the parties to avoid a feud that could escalate into an ever-widening conflict involving kin descended from different ancestors. He urges the aggrieved family to accept compensation, usually in the form of cattle. When such an agreement is reached, the chief collects the 40 to 50 head of cattle and takes them to the dead man’s home, where he performs various sacrifices of cleansing and atonement.[27]

This discussion demonstrates the preference most tribal societies have for mediation given the potentially serious consequences of a long-term feud. Even in societies organized as states, mediation is often preferred. In the agrarian town of Talea, Mexico, for example, even serious crimes are mediated in the interest of preserving a degree of local harmony. The national authorities often tolerate local settlements if they maintain the peace.[28]

Quick Reading Check: Think of your family or close friends as a social unit lacking a strict “codified law.” Describe a way that an individual may be punished and how those punishments are organized.

7.2.7 Warfare in Tribal Societies

What happens if mediation fails and the Leopard Skin Chief cannot convince the aggrieved clan to accept cattle in place of their loved one? War. In tribal societies, wars vary in cause, intensity, and duration, but they tend to be less deadly than those run by states because of tribes’ relatively small populations and limited technologies.

Tribes engage in warfare more often than bands, both internally and externally. Among pastoralists, both successful and attempted thefts of cattle frequently spark conflict. Among pre-state societies, pastoralists have a reputation for being the most prone to warfare. However, horticulturalists also engage in warfare, as the film Dead Birds, which describes warfare among the highland Dani of west New Guinea (Irian Jaya), attests. Among anthropologists, there is a “protein debate” regarding causes of warfare. Marvin Harris in a 1974 study of the Yanomami claimed that warfare arose there because of a protein deficiency associated with a scarcity of game, and Kenneth Good supported that thesis in finding that the game a Yanomami villager brought in barely supported the village.[29] He could not link this variable to warfare, however. In rebuttal, Napoleon Chagnon linked warfare among the Yanomami with abduction of women rather than disagreements over hunting territory, and findings from other cultures have tended to agree with Chagnon’s theory.[30]

Tribal wars vary in duration. Raids are short-term uses of physical force that are organized and planned to achieve a limited objective such as acquisition of cattle (pastoralists) or other forms of wealth and, often, abduction of women, usually from neighboring communities.[31] Feuds are longer in duration and represent a state of recurring hostilities between families, lineages, or other kin groups. In a feud, the responsibility to avenge rests with the entire group, and the murder of any kin member is considered appropriate because the kin group as a whole is considered responsible for the transgression. Among the Dani, for example, vengeance is an obligation; spirits are said to dog the victim’s clan until its members murder someone from the perpetrator’s clan.[32]

Quick Reading Check: Describe two different ways in which tribal societies engage in warfare.

Media Attributions

- Mbuti women © Wikipedia is licensed under a CC0 (Creative Commons Zero) license

- Bilateral cross-cousin marriage © Kendall Hunt Publishing Company is licensed under a All Rights Reserved license

- Segmentary lineage model © Kendall Hunt Publishing Company is licensed under a All Rights Reserved license

- Julian Steward, The Theory of Culture Change: The Methodology of Multilinear Evolution (Urbana: University of Illinois Press, 1955), 54. ↵

- Elman Service, Origins of the State and Civilization. ↵

- Morton Fried, The Evolution of Political Society. ↵

- Richard Lee, The Dobe Ju/’hoansi, 109–111. ↵

- Julian Steward, The Theory of Culture Change. ↵

- Elman Service, Primitive Social Organization: An Evolutionary Perspective (New York: Random House, 1962). ↵

- M. Kay Martin and Barbara Voorhies, Female of the Species (New York: Columbia University Press, 1975). ↵

- E. Adamson Hoebel, The Law of Primitive Man, 168. ↵

- See Colin Turnbull, The Forest People: A Study of the Pygmies of the Congo (New York: Simon and Schuster, 1963) and Colin Turnbull, The Mbuti Pygmies: Change and Adaptation (New York: Holt, Rinehart and Winston, 1983). ↵

- C.W. Merton Hart, Arnold R. Pilling, and Jane Goodale. The Tiwi of North Australia (New York: Holt, Rinehart and Winston, 1988). ↵

- Richard Lee, The Dobe Ju/’hoansi, 112–118. ↵

- Napoleon Chagnon, Yanomamo (New York: Holt, Rinehart and Winston, 1997), 133–137. ↵

- Marcel Mauss, The Gift: The Form and Reason for Exchange in Archaic Societies (London: Routledge, 2001 [1925]). ↵

- Douglas Oliver, A Solomon Island Society: Kinship and Leadership among the Siuai of Bougainville (Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 1955). For an account of Ongka, the big man in a Kawelka village, see Andrew Strathern and Pamela J. Stewart, Collaborations and Conflict: A Leader through Time (Belmont, CA: Wadsworth, 1999). ↵

- Walter Sangree, “The Bantu Tiriki of Western Kenya,” in Peoples of Africa, James Gibbs, ed. (New York: Holt, Rinehart and Winston, 1965), 71. The reader will notice the discrepancies between Sangree’s description of age grades and sets—15 year for each, totaling a cycle of 105 years—and his chart from which the one shown here is extrapolated to 1994. First, the age grade “small boys,” is 10 years, not 15. Second, the age grade “ritual elders” is 20 years, not 15. Why this discrepancy exists, Sangree does not answer. This discrepancy demonstrates the ques- tions raised when ideal types do not match all the ethnographic information. For example, if the Jiminigayi ranged 15 years in 1939, why did they suddenly expand to a range of 20 years in 1954? By the same token, why did the Sawe age set cover 10 years in 1939 and expand to 15 years in 1954? It is discrepancies such as this that raise questions and drive further research ↵

- Mervyn Meggitt, Blood Is Their Argument: Warfare among the Mae-Enga (Palo Alto, CA: Mayfield, 1977) 202–224. ↵

- Marcel Mauss, The Gift. ↵

- Ibid ↵

- Ibid ↵

- Claude Levi-Strauss’ concept is further described in Robin Fox, Kinship and Marriage (Harmondsworth, UK: Penguin, 1967), 182–187. ↵

- Evans-Pritchard, Edward E. The Nuer. Oxford, UK: Oxford University Press, 1940. ↵

- Paul Bohannan, Justice and Judgment among the Tiv. Prospect Heights, IL: Waveland Press, 1989. And Murphy, Robert F, and Leonard Kasdan. “The Structure of Parallel Cousin Marriage.” American Anthropologist 61 no. 1 (1959.):17–29. ↵

- Marshall Sahlins, “The Segmentary Lineage: An Organization of Predatory Expansion.” American Anthropologist 63 (1961):322–343. ↵

- Ibid ↵

- E.E. Evans-Pritchard, Witchcraft, Oracles, and Magic among the Azande (Oxford: Oxford University Press,1976). ↵

- Klaus-Friedrich Koch et al., “Ritual Reconciliation and the Obviation of Grievances: A Comparative Study in the Ethnography of Law.” Ethnology 16 (1977):269–270. ↵

- E.E. Evans-Pritchard, The Nuer (Oxford, UK: Oxford University Press, 1940), 291. ↵

- Laura Nader, Harmony Ideology: Justice and Control in a Zapotec Mountain Village. (Stanford: Stanford University Press, 1991). ↵

- Marvin Harris, Cows, Pigs, Wars, and Witches. New York: Vintage, 1974. Good, Kenneth. Into The Heart: One Man’s Pursuit of Love and Knowledge among the Yanomami. Upper Saddle River, NJ: Prentice-Hall, 1997 ↵

- Napoleon Chagnon, Yanomamo, 91–97. ↵

- Douglas White, “Rethinking Polygyny, Co-wives, Codes, and Cultural Systems,” Current Anthropology 29 no. 4 (1988): 529–533 ↵

- Karl Heider, The Dugum Dani: A Papuan Culture in the Highlands of West New Guinea (Chicago: Aldine, 1970). ↵

the smallest unit of political organization, consisting of only a few families and no formal leader- ship positions.

political units organized around family ties that have fluid or shifting systems of temporary leadership.

societies in which there are substantial differences in the wealth and social status of individuals; there are a limited number of positions of power or status, and only a few can occupy them.

societies in which there are large differences in the wealth, status, and power of individuals based on unequal access to resources and positions of power.

the division of society into groups based on wealth and status.

a form of temporary or situational leadership; influence results from acquiring followers. Bilateral cross-cousin marriage: a man marries a woman who is both his mother’s brother’s daughter and his father’s sister’s daughter.

individuals who can trace or demonstrate their descent through a line of males or females back to a founding ancestor.

named categories to which men of a certain age are assigned at birth.

groups of men who are close to one another in age and share similar duties or responsibilities.

short-term uses of physical force organized and planned to achieve a limited objective.

family relationships created through marriage.

a marriage system in which only two extended families can engage in this exchange.

formal legal systems in which damages, crimes, remedies, and punishments are specified. Egalitarian: societies in which there is no great difference in status or power between individuals and there are as many valued status positions in the societies as there are persons able to fill them.

the practice of calling on a deity to bear witness to the truth of what one says.

a test used to determine guilt or innocence by submitting the accused to dangerous, painful, or risky tests believed to be controlled by supernatural forces.

disputes of long duration characterized by a state of recurring hostilities between families, lineages, or other kin groups.