3.1 What Exactly Is Anthropological Fieldwork?

Fieldwork can take many forms depending on the perspective you are using and the “field(s)” you are visiting. The “field” can be anywhere the people are—a village in highland Papua, New Guinea or a supermarket in downtown Minneapolis. Just as marine biologists spend time in the ocean to learn about the behavior of marine animals and geologists travel to a mountain range to observe rock formations, anthropologists go to places where people are to learn about the research questions they are asking.

To get a basic understanding of what fieldwork can look like, we want you to watch Doing Anthropology, a short 8 minute film where Stefan Helmreich, Erica James, and Heather Paxson, three members of the Massachusetts Institute of Technology’s Anthropology Department, talk about their current work and the process of doing fieldwork. This film will provide you with an introductory understanding of some of the types of fieldwork done by cultural anthropologists and their importance for gaining an in-depth perspective on the research.

Fieldwork is the most important method by which cultural anthropologists gather data to answer their research questions. While interacting on a daily basis with a group of people, cultural anthropologists document their observations and perceptions and adjust the focus of their research as needed. They typically spend a few months to a few years living among the people they are studying.

Katie Nelson’s Story of Anthropological Fieldwork

My (Katie’s) first experience with fieldwork as a student anthropologist took place in a small indigenous community in northeastern Brazil studying the Jenipapo-Kanindé of Lagoa Encantada (Enchanted Lake). I had planned to conduct an independent research project on land tenure among members of the indige- nous tribe and had gotten permission to spend several months with the community. My Brazilian host family arranged for a relative to drive me to the rural community on the back of his motorcycle. After several hours navigating a series of bumpy roads in blazing equatorial heat, I was relieved to arrive at the edge of the reservation. He cut the motor and I removed my heavy backpack from my tired, sweaty back. Upon hearing us arrive, first children and then adults slowly and shyly began to approach us. I greeted the curious onlookers and briefly explained who I was. As a group of children ran to fetch the cacique (the chief/political leader), I began to explain my research agenda to several of the men who had gathered. I mentioned that I was interested in learning about how the tribe negotiated land use rights without any private land ownership. After hearing me use the colloquial term “índio” (Indian), a man who turned out to be the cacique’s cousin came forward and said to me, “Well, your work is going to be difficult because there are no Indians here; we are only Brazilians.” Then, abruptly, another man angrily replied to him, stating firmly that, in fact, they were Indians because the community was on an Indian reservation and the Brazilian government had recognized them as an indigenous tribe. A few women then entered the rapid-fire discussion. I took a step back, surprised by the intensity of my first interac- tion in the community. The debate subsided once the cacique arrived, but it left a strong impression in my mind. Eventually, I discarded my original research plan to focus instead on this disagreement within the community about who they were and were not. In anthropology, this type of conflict in beliefs is known as contested identity.

I soon learned that many among the Jeni- papo-Kanindé did not embrace the Indian identity label. The tribe members were all monolingual Portuguese-speakers who long ago had lost their original language and many of their traditions. Beginning in the 1980s, several local researchers had conducted studies in the community and had concluded that the community had indigenous origins. Those researchers lobbied on the community’s behalf for official state and federal status as an indige- nous reservation, and in 1997 the Funai (Fundação Nacional do Índio or National Foundation for the Indian) visited the community and agreed to officially demarcate the land as an indigenous reservation.

More than 20 years later, the community is still waiting for that demarcation. Some in the community embraced indigenous status because it came with a number of benefits. The state (Ceará), using partial funding from Funai, built a new road to improve access to the community. The government also constructed an elementary school and a common well and installed new electric lines. Despite those gains, some members of the community did not embrace indigenous status because being considered Indian had a pejorative connotation in Brazil. Many felt that the label stigmatized them by associating them with a poor and marginalized class of Brazilians. Others resisted the label because of long-standing family and interpersonal conflicts in the community.

3.1.2 How can we make the Strange Familiar and the Familiar Strange?

The cultural anthropologist’s goal during fieldwork is to describe a group of people to others in a way that makes strange or unusual features of the culture seem familiar and familiar traits seem extraordinary. The point is to help people think in new ways about aspects of their own culture by comparing them with other cultures.

Margaret Mead: A historical example of Defamiliarizing the Familiar

The anthropologist Margaret Mead describes a famous example of defamiliarizing the familiar in her monograph Coming of Age in Samoa (1928). In 1925, Mead went to American Samoa, where she conducted ethnographic research on adolescent girls and their experiences with sexuality and growing up. Mead’s mentor, anthropologist Franz Boas, was a strong proponent of cultural determinism, the idea that one’s cultural upbringing and social environment, rather than one’s biology, primarily determine behavior. Boas encouraged Mead to travel to Samoa to study adolescent behavior there and to compare their culture and behavior with that of adolescents in the United States to lend support to his hypothesis. In the foreword of Coming of Age in Samoa, Boas described what he saw as the key insight of her research: “The results of her painstaking investigation confirm the suspicion long held by anthropologists that much of what we ascribe to human nature is no more than a reaction to the restraints put upon us by our civilization.”[1]

Mead studied 25 young women in three villages in Samoa and found that the stress, anxiety, and tur- moil of American adolescence were not found among Samoan youth. Rather, young women in Samoa experienced a smooth transition to adulthood with relatively little stress or difficulty. She documented instances of socially accepted sexual experimentation, lack of sexual jealousy and rape, and a general sense of casualness that marked Samoan adolescence.

Coming of Age in Samoa quickly became popular, launching Mead’s career as one of the most well-known anthropologists in the United States and perhaps the world. The book encouraged American readers to reconsider their own cultural assumptions about what adolescence in the United States should be like, particularly in terms of the sexual repression and turmoil that seemed to characterize the teenage experience in mid-twentieth century America. Through her analysis of the differences between Samoan and American society, Mead also persuasively called for changes in education and parenting for U.S. children and adolescents. Now, almost a 100 years later, there is still a need for these changes.

A pop culture video example of making the familiar strange can be seen in the Morning Routine title sequence of the mid-2000s show Dexter, an American crime drama. This show tells the story of a vigilante serial killer who kills murderers who have escaped the punishment of the criminal justice system. What is most interesting to this story for me, Vanessa, as an anthropologist is how the producers of the show created the Morning Routine title sequence.

See for Yourself:

This video highlights Dexter’s morning routine as both normal and unfamiliar. Like Horace Miner’s Body Ritual of the Nacirema, this video pushes the viewer to both see themselves in Dexter and feel a bit uneasy because what is a normal morning is shown with images that can be viewed in multiple ways.

Quick Reading Check: What does it mean to make the familiar strange and/or defamiliarize the familiar? Provide your own example.

3.1.3: Emic versus Etic Perspectives: How are both important to Anthropological Fieldwork?

When anthropologists conduct fieldwork, they gather data. An important tool for gathering anthropological data is ethnography—the in-depth study of everyday practices and lives of a people. Ethnography produces a detailed description of the studied group at a particular time and location, also known as a “thick description,” a term coined by anthropologist Clifford Geertz in his 1973 book The Interpretation of Cultures to describe this type of research and writing. A thick description explains not only the behavior or cultural event in question but also the context in which it occurs and anthropological interpretations of it. Such descriptions help readers better understand the internal logic of why people in a culture behave as they do and why the behaviors are meaningful to them. This is important because understanding the attitudes, perspectives, and motivations of cultural insiders is at the heart of anthropology.

Ethnographers gather data from many different sources. One source is the anthropologist’s own observations and thoughts. Ethnographers keep field notebooks that document their ideas and reflections as well as what they do and observe when participating in activities with the people they are studying, a research technique known as participant observation. Other sources of data include informal conversations and more-formal interviews that are recorded and transcribed. They also collect documents such as letters, photographs, artifacts, public records, books, and reports.

Different types of data produce different kinds of ethnographic descriptions, which also vary in terms of perspective—from the perspective of the studied culture (emic) or from the perspective of the observer (etic). Emic perspectives refer to descriptions of behaviors and beliefs in terms that are meaningful to people who belong to a specific culture, e.g., how people perceive and categorize their culture and experiences, why people believe they do what they do, how they imagine and explain things. To uncover emic perspectives, ethnographers talk to people, observe what they do, and participate in their daily activities with them. Emic perspectives are essential for anthropologists’ efforts to obtain a detailed understanding of a culture and to avoid interpreting others through their own cultural beliefs. Etic perspectives refer to explanations for behavior by an outside observer in ways that are meaningful to the observer. For an anthropologist, etic descriptions typically arise from conversations between the ethnographer and the anthropological community. These explanations tend to be based in science and are informed by historical, political, and economic studies and other types of research.

The etic approach acknowledges that members of a culture are unlikely to view the things they do as noteworthy or unusual. They cannot easily stand back and view their own behavior objectively or from another perspective. For example, you may have never thought twice about the way you brush your teeth and the practice of going to the dentist or how you experienced your teenage years. For you, these parts of your culture are so normal and “natural” you probably would never consider questioning them. An emic lens gives us an alternative perspective that is essential when constructing a comprehensive view of a people.

Most often, ethnographers include both emic and etic perspectives in their research and writing. They first uncover a studied people’s understanding of what they do and why and then develop additional explanations for the behavior based on anthropological theory and analysis. Both perspectives are important, and it can be challenging to move back and forth between the two. Nevertheless, that is exactly what good ethnographers must do.

Quick Reading Check: What is anthropological fieldwork and where can it be done?

Media Attributions

- Katie Nelson and host family © Missing Source is licensed under a All Rights Reserved license

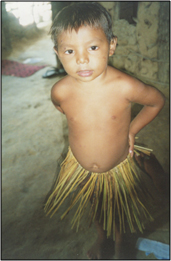

- Jenipapo Kanindé boy © Missing Source is licensed under a All Rights Reserved license

- Franz Boas, “Foreword,” in Coming of Age in Samoa by Margaret Mead (New York: William Morrow, 1928). ↵

people who have continually lived in a particular location for a long period of time (prior to the arrival of others) or who have historical ties to a location and who are culturally distinct from the dominant population surrounding them. Other terms used to refer to indigenous people are aboriginal, native, original, first nation, and first people. Some examples of indigenous people are Native Ameri- cans of North America, Australian Aborigines, and the Berber (or Amazigh) of North Africa.

how property rights to land are allocated within societies, including how permissions are granted to access, use, control, and transfer land.

a dispute within a group about the collective identity or identities of the group. Cultural relativism: the idea that we should seek to understand another person’s beliefs and behaviors from the perspective of their own culture and not our own.

a set of beliefs, practices, and symbols that are learned and shared. Together, they form an all-encompassing, integrated whole that binds people together and shapes their worldview and lifeways.

the idea that behavioral differences are a result of cultural, not racial or genetic causes.

the in-depth study of the everyday practices and lives of a people.

a term coined by anthropologist Clifford Geertz in his 1973 book The Interpretation of Cultures to describe a detailed description of the studied group that not only explains the behavior or cultural event in question but also the context in which it occurs and anthropological interpretations of it.

a type of observation in which anthropologists observe while participating in the same activities in which their informants are engaged.

a description of the studied culture from the perspective of a member of the culture or insider. Ethnocentrism: the tendency to view one’s own culture as most important and correct and as the stick by which to measure all other cultures.

a description of the studied culture from the perspective of an observer or outsider.