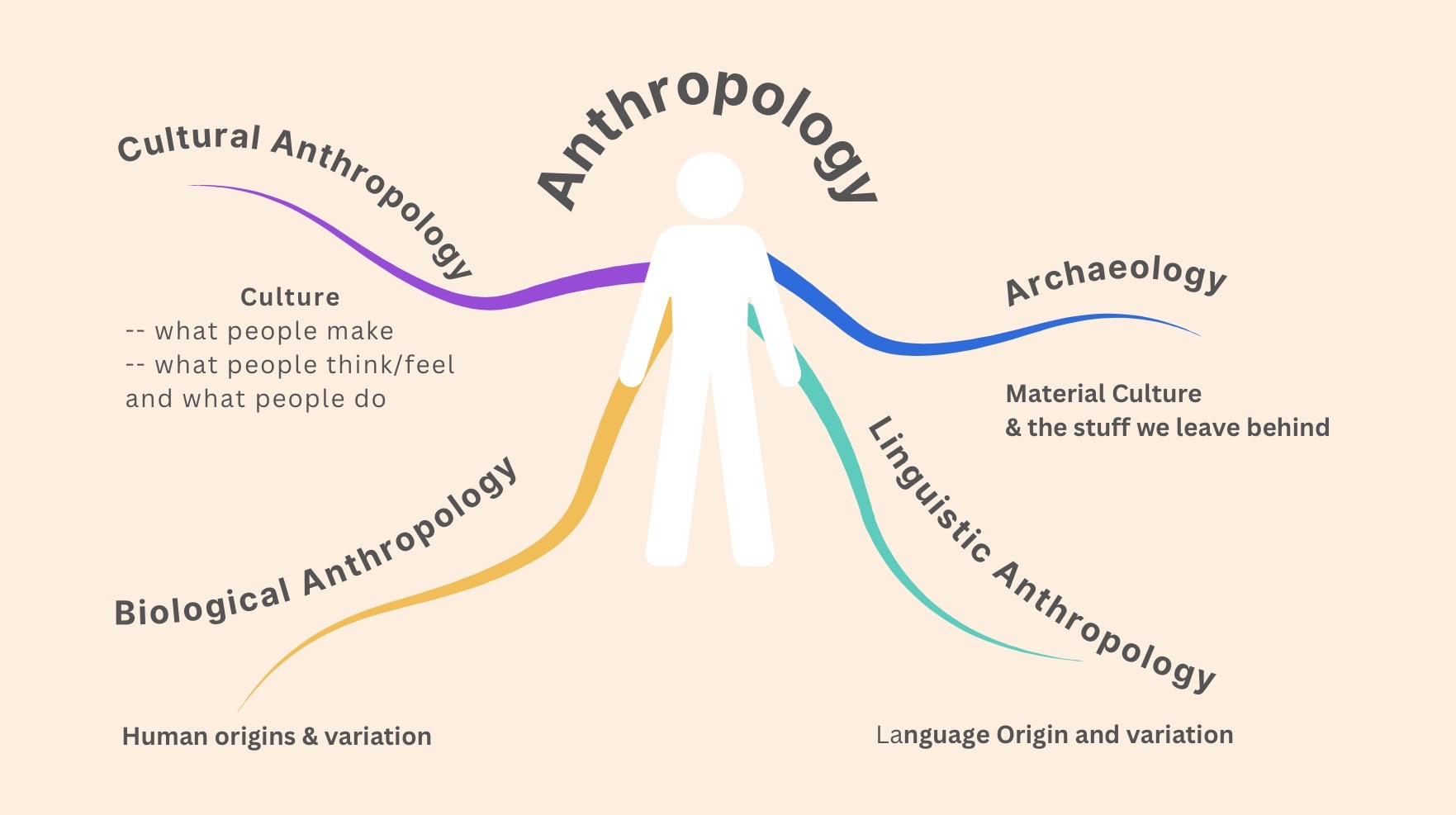

1.4 Beyond Cultural Anthropology

1.4.1 What is Biological Anthropology?

Biological anthropology is the study of human origins, evolution, and variation. Some biological anthropologists focus on our closest living relatives, monkeys and apes. They examine the biological and behavioral similarities and differences between nonhuman primates and human primates (us!). For example, Jane Goodall has devoted her life to studying wild chimpanzees (Goodall 1996). When she began her research in Tanzania in the 1960s, Goodall challenged widely held assumptions about the inherent differences between humans and apes. At the time, it was assumed that monkeys and apes lacked the social and emotional traits that made human beings such exceptional creatures. However, Goodall discovered that, like humans, chimpanzees also make tools, socialize their young, have intense emotional lives, and form strong maternal-infant bonds. Her work highlights the value of field-based research in natural settings that can help us understand the complex lives of nonhuman primates.

Other biological anthropologists focus on extinct human species, asking questions like: What did our ancestors look like? What did they eat? When did they start to speak? How did they adapt to new environments? In 2013, a team of women scientists excavated a trove of fossilized bones in the Dinaledi Chamber of the Rising Star Cave system in South Africa. The bones turned out to belong to a previously unknown hominin species that was later named Homo naledi. With over 1,550 specimens from at least fifteen individuals, the site is the largest collection of a single hominin species found in Africa (Berger, 2015). Researchers are still working to determine how the bones were left in the deep, hard to access cave and whether or not they were deliberately placed there. Here is a short National Geographic clip that discusses this. They also want to know what Homo naledi ate, if this species made and used tools, and how they are related to other Homo species. Biological anthropologists who study ancient human relatives are called paleoanthropologists. The field of paleoanthropology changes rapidly as fossil discoveries and refined dating techniques offer new clues into our past.

Other biological anthropologists focus on humans in the present including their genetic and phenotypic (observable) variation. For instance, Nina Jablonski has conducted research on human skin tone, asking why dark skin pigmentation is prevalent in places, like Central Africa, where there is high ultraviolet (UV) radiation from sunlight, while light skin pigmentation is prevalent in places, like Nordic countries, where there is low UV radiation. She explains this pattern in terms of the interplay between skin pigmentation, UV radiation, folic acid, and vitamin D. In brief, too much UV radiation can break down folic acid, which is essential to DNA and cell production. Dark skin helps block UV, thereby protecting the body’s folic acid reserves in high-UV contexts. Light skin evolved as humans migrated out of Africa to low-UV con texts, where dark skin would block too much UV radiation, compromising the body’s ability to absorb vitamin D from the sun. Vitamin D is essential to calcium absorption and a healthy skeleton. Jablonski’s research shows that the spectrum of skin pigmentation we see today evolved to balance UV exposure with the body’s need for vitamin D and folic acid (Jablonski 2012). For more information regarding Jablonski’s work please review The Evolution of Skin Color website.

Quick Reading Check: What types of questions are biological anthropologists interested in and why?

1.4.2 What does it mean to be an archaeologist? What is material culture?

Take a look around you, chances are you are surrounded by “stuff”. From the clothing you are wearing to the screen you are staring at and the vessel from which you are drinking, much of our culture plays out in the material world in some form. After all, it is this stuff or what anthropologists call material culture which separates us from other living things on earth. Now picture if all that was left of your existence is the stuff surrounding you. This is the situation that archaeologists often face when trying to examine culture. Archaeologists focus on the material past: the tools, food, pottery, art, shelters, seeds, and other objects left behind by people. Prehistoric archaeologists recover and analyze these materials to reconstruct the lifeways of past societies that lacked writing. They ask specific questions like: How did people in a particular area live? What did they eat? Why did their societies change over time? They also ask general questions about humankind: When and why did humans first develop agriculture? How did cities first develop? How did prehistoric people interact with their neighbors? The method that archaeologists use to answer their questions is excavation—the careful digging and removal of dirt and stones to uncover material remains while recording their context. Archaeological research spans millions of years from human origins to the present. For example, British archaeologist Kathleen Kenyon (1906-1978), was one of few female archaeologists in the 1940s. She famously studied the city structures and cemeteries of Jericho, an ancient city dating back to the Early Bronze Age (3,200 years before the present) located in what is today the West Bank. Based on her findings, she argued that Jericho is the oldest city in the world and has been continuously occupied by different groups for over 10,000 years (Kenyon 1979).

Historical archaeologists study recent societies using material remains to complement the written record. The Garbage Project, which began in the 1970s, is an example of a historic archaeological project based in Tucson, Arizona. It involves excavating a contemporary landfill as if it were a conventional archaeology site. Archaeologists have found discrepancies between what people say they throw out and what is actually in their trash. In fact, many landfills hold large amounts of paper products and construction debris (Rathje and Murphy 1992). This finding has practical implications for creating environmentally sustainable waste disposal practices.

In 1991, while working on an office building in New York City, construction workers came across human skeletons buried just 30 feet below the city streets. Archaeologists were called in to investigate. Upon further excavation, they discovered a six-acre burial ground, containing 15,000 skeletons of free and enslaved Africans who helped build the city during the colonial era. The “African Burial Ground,” which dates from 1630 to 1795, contains a trove of information about how free and enslaved Africans lived and died. The site is now a national monument where people can learn about the history of slavery in the U.S.[1]

Quick Reading Check: What type of research archaeologists do and what aspects of humanity do they study?

1.4.3 What is Linguistic Anthropology?

Language is a defining cultural trait of human beings. While other animals have communication systems, only humans have complex, symbolic languages—over 6,000 of them! Human language makes it possible to teach and learn, to plan and think abstractly, to coordinate our efforts, and even to contemplate our own demise. Linguistic anthropologists ask questions like: How did language first emerge? How has it evolved and diversified over time? How has language helped us succeed as a species? How can language convey one’s social identity? How does language influence our views of the world?

If you speak two or more languages, you may have experienced how language affects you. For example, in English, we say: “I love you.” But Spanish speakers use different terms—te amo, te adoro, te quiero, and so on—to convey different kinds of love: romantic love, platonic love, maternal love, etc. The Spanish language arguably expresses more nuanced views of love than the English language.

One intriguing line of linguistic anthropological research focuses on the relationship between language, thought, and culture. It may seem intuitive that our thoughts come first; after all, we like to say: “Think before you speak.” However, according to the Sapir-Whorf Hypothesis (also known as linguistic relativity), the language you speak allows you to think about some things and not others. When Benjamin Whorf (1897-1941) studied the Hopi language, he found not just word-level differences, but grammatical differences between Hopi and English. He wrote that Hopi has no grammatical tenses to convey the passage of time. Rather, the Hopi language indicates whether or not something has “manifested.” Whorf argued that English grammatical tenses (past, present, future) inspire a linear sense of time, while Hopi language, with its lack of tenses, inspires a cyclical experience of time (Whorf 1956).

Some critics, like German-American linguist Ekkehart Malotki, refute Whorf’s theory, arguing that Hopi do have linguistic terms for time and that a linear sense of time is natural and perhaps universal. At the same time, Malotki recognized that English and Hopi tenses differ, albeit in ways less pronounced than Whorf proposed (Malotki 1983). Other linguistic anthropologists track the emergence and diversification of languages, while others focus on language use in today’s social contexts. Still others explore how language is crucial to socialization: children learn their culture and social identity through language and nonverbal forms of communication (Ochs and Schieffelin 2012).

Quick Reading Check: What is linguistic anthropology and what elements of communication are they interested in?

1.4.4 Applied Anthropology

Applied anthropology involves the application of anthropological theories, methods, and findings to solve practical problems. Applied anthropologists are employed outside of academic settings, in both the public and private sectors, including business or consulting firms, advertising companies, city government, law enforcement, the medical field, non governmental organizations, and even the military.

Applied anthropologists span all four of the subfields. An applied archaeologist might work in cultural resource management to assess a potentially significant archaeological site unearthed during a construction project. An applied cultural anthropologist could work at a technology company that seeks to understand the human-technology interface in order to design better tools.

Medical anthropology is an example of both an applied and theoretical area of study that draws on all four subdisciplines to understand the interrelationship of health, illness, and culture. Rather than assume that disease resides only within the individual body, medical anthropologists explore the environmental, social, and cultural conditions that impact the experience of illness. For example, in some cultures, people believe illness is caused by an imbalance within the community. Therefore, a communal response, such as a healing ceremony, is necessary to restore both the health of the person and the group. This approach differs from the one used in mainstream U.S. healthcare, whereby people go to a doctor to find the biological cause of an illness and then take medicine to restore the individual body. Trained as both a physician and medical anthropologist, the late Paul Farmer demonstrates the applied potential of anthropology. During his college years in North Carolina, Farmer’s interest in the Haitian migrants working on nearby farms inspired him to visit Haiti. There, he was struck by the poor living conditions and lack of health care facilities. Later, as a physician, he would return to Haiti to treat individuals suffering from diseases like tuberculosis and cholera that were rarely seen in the United States. As an anthropologist, he would contextualize the experiences of his Haitian patients in relation to the historical, social, and political forces that impact Haiti, the poorest country in the Western Hemisphere (Farmer 2006). He died in February 2022, but his academic writing and his activism in the world live on through the people he has inspired and the work of Partners in Health, a nonprofit organization that he co-founded. He helped open health clinics in many resource-poor countries and trained local staff to administer care. In this way, he applied his medical and anthropological training to improve people’s lives.

Quick Reading Check: How does applied anthropology differ from academic anthropology?

Media Attributions

- Anthropology subfields © Vanessa Martínez is licensed under a CC BY-NC-SA (Attribution NonCommercial ShareAlike) license

- https://www.nps.gov/afbg/index.htm ↵

Humans (Homo sapiens) and their close relatives and immediate ancestors.

Quick reading check: Explain this statement in your own words - "Certainly, humans vary in terms of physical and genetic characteristics such as skin color, hair texture, and eye shape, but those variations cannot be used as criteria to biologically classify racial groups with scientific accuracy." Make sure to explain both parts of the sentence.

Anthropology was sometimes referred to as the “science of race” during the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries when physical anthropologists sought a biological basis for categorizing humans into racial types.[1] Since World War II, important research by anthropologists has revealed that racial categories are socially and culturally defined concepts and that racial labels and their definitions vary widely around the world. In other words, different countries have different racial categories and different ways of classifying their citizens into these categories.[2] At the same time, significant genetic studies conducted by physical anthropologists since the 1970s have revealed that biologically distinct human races do not exist. Certainly, humans vary in terms of physical and genetic characteristics such as skin color, hair texture, and eye shape, but those variations cannot be used as criteria to biologically classify racial groups with scientific accuracy. Let us turn our attention to understanding why humans cannot be scientifically divided into biologically distinct races.

9.3.1 Race: A Discredited Concept in Human Biology

At some point in your life, you have probably been asked to identify your race on a college form, job application, government or military form, or some other official document. And most likely, you were required to select from a list of choices rather than given the ability to respond freely. The frequency with which we are exposed to four or five common racial labels—“white,” “Black,” “Caucasian,” and “Asian,” for example—tends to promote the illusion that racial categories are natural, objective, and evident divisions. After all, if Justin Timberlake, Jay-Z, and Jackie Chan stood side by side, those common racial labels might seem to make sense. What could be more objective, more conclusive, than this evidence before our very eyes? By this point, you might be thinking that anthropologists have gone completely insane in denying biological human races! But the reality is that “race” is much more complicated than what we think we know about it. An average person’s understanding of race is so incomplete and inaccurate because of the ever-changing and random social rules about race.

Physical anthropologists have identified several important concepts regarding the true nature of humans’ physical, genetic, and biological variation that have discredited race as a biological concept. Many of the issues presented in this section are discussed in further detail in Understanding Race: Are We So Different?, a website created by the American Anthropological Association. The American Anthropological Association (AAA) launched the website to educate the public about the true nature of human biological and cultural variation and challenge common misperceptions about race. This is an important endeavor because race is a complicated, often emotionally charged topic, leading many people to rely on their personal opinions and hearsay when concluding people are different from them. The website is highly interactive, featuring multimedia illustrations and online quizzes designed to increase visitors’ knowledge of human variation. This website has been recently updated by an advisory board, which included me (Vanessa), to ensure that it could be used as an educational website for middle school to college. We encourage you to explore the website as you will likely find answers to several of the questions you may still be asking after reading this chapter.[3]

Before explaining why distinct biological races do not exist among humans, I must point out that one of the biggest reasons so many people continue to believe in the existence of biological human races is that the idea has been intensively reified in literature, the media, and culture for more than three hundred years. Reification refers to the process in which an inaccurate concept or idea is so heavily promoted and circulated among people that it begins to take on a life of its own. Reification makes it very difficult to unlearn the false narrative and create a more accurate one. Over centuries, the notion of biological human races became ingrained—unquestioned, accepted, and regarded as a concrete “truth.” Studies of human physical and cultural variation from a scientific and anthropological perspective have allowed scholars to move beyond reified thinking and toward an improved understanding of the true complexity of human diversity. That said, we continue to struggle to share this knowledge about race with the general public.

The reification of race has a long history. Especially during the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries, philosophers and scholars attempted to identify various human races. They perceived “races” as specific divisions of humans who shared certain physical and biological features that distinguished them from other groups of humans. This historic notion of race may seem clear-cut and innocent enough, but it quickly led to problems as social theorists attempted to classify people by race. One of the most basic difficulties was the actual number of human races: how many were there, who were they, and what grounds distinguished them? Despite more than three centuries of such effort, no clear-cut scientific consensus was established for a precise number of human races. Instead, science eventually proved that biological races were not a “real” thing.

One of the earliest and most influential attempts at producing a racial classification system came from Swedish botanist Carolus Linnaeus, who argued in Systema Naturae (1735) for the existence of four human races: Americanus (Native American / American Indian), Europaeus (European), Asiaticus (East Asian), and Africanus (African). These categories correspond with common racial labels used in the United States for census and demographic purposes today. However, in 1795, German physician and anthropologist Johann Blumenbach suggested that there were five races, which he labeled as Caucasian (white), Mongolian (yellow or East Asian), Ethiopian (Black or African), American (red or American Indian), Malayan (brown or Pacific Islander). Importantly, Blumenbach listed the races in this exact order, which he believed reflected their natural historical descent from the “primeval”

Caucasian original to “extreme varieties.”[4]

Although he was a committed abolitionist, Blumenbach nevertheless felt that his “Caucasian” race (named after the Caucasus Mountains of Central Asia, where he believed humans had originated) represented the original variety of humankind from which the other races had degenerated. By the early twentieth century, many social philosophers and scholars had accepted the idea of three human races: the so-called Caucasoid, Negroid, and Mongoloid groups that corresponded with regions of Europe, sub-Saharan Africa, and East Asia, respectively. However, the three-race theory faced serious criticism given that numerous peoples from several geographic regions were omitted from the classification, including Australian Aborigines, Asian Indians, American Indians, and inhabitants of the South Pacific Islands. Those groups could not be easily pigeonholed into racial categories regardless of how loosely the categories were defined. Australian Aborigines, for example, often have dark complexions (a trait they appeared to share with Africans) but reddish or blondish hair (a trait shared with northern Europeans). Likewise, many Indians living on the Asian subcontinent have complexions that are as dark or darker than those of many Africans and African Americans. Because of these seeming contradictions and some observable differences between people categorized within a possible racial group, some academics began to argue in favor of larger numbers of human races—five, nine, twenty, sixty, and more.[5]

The fundamental point here is that any effort to classify human populations into racial categories is inherently arbitrary and subjective rather than scientific and objective. These racial classification schemes simply reflected their proponents’ desires to “slice the pie” of human physical variation according to the particular trait(s) they preferred to establish as the major, defining criteria of their classification system. Two major types of “race classifiers” have emerged over the past 300 years: lumpers and splitters. Lumpers have classified races by large geographic tracts (often continents) and produced a small number of broad, general racial categories, as reflected in Linnaeus’s original classification scheme and later three-race theories. Splitters have subdivided continent-wide racial categories into specific, more localized regional races and attempted to devise more “precise” racial labels for these specific groups, such as the three European races described earlier. Consequently, splitters have tried to identify many more human races than lumpers.

Racial labels, whether from a lumper or a splitter model, clearly attempt to identify and describe something. So why do these racial labels not accurately describe human physical and biological variation? To understand why, we must keep in mind that racial labels are distinct, discrete categories while human physical and biological variations (such as skin color, hair color and texture, eye color, height, nose shape, and distribution of blood types) are continuous rather than discrete. But what exactly does it mean to say that physical variation is continuous and not discrete?

Physical anthropologists use the term cline to refer to differences in the traits that occur in populations across a geographical area. In a cline, a trait may be more common in one geographical area than another, but the variation is gradual and continuous with no sharp breaks. A prominent example of clinal variation among humans is skin color. Think of it this way: Do all “white” persons that you know actually

share the same skin complexion? Likewise, do all “Black” persons that you know share an identical skin complexion? The answer obviously, is no, since human skin color does not occur in just 3, 5, or even 50 shades.

The reality is that human skin color, as a continuous trait, exists as a spectrum from very light to very dark with every possible hue, shade, and tone in between.

Imagine THIS

Imagine two people—one from Sweden and one from Nigeria—standing side by side. If we looked only at those two individuals and ignored people who inhabit the regions between Sweden and Nigeria, it would be easy to reach the faulty (inaccurate) conclusion that they represented two distinct human racial groups, one light (“white”) and one dark (“Black”).[6] However, if we walked from Nigeria to Sweden, we would gain a fuller understanding of human skin color because we would have seen that skin color generally became gradually lighter the further north we traveled from the equator. At no point during this imaginary walk would we reach a point at which the people abruptly changed skin color.

As physical anthropologists such as John Relethford (2004) and C. Loring Brace (2005) have noted, the average range of skin color gradually changes over geographic space. North Africans are generally lighter-skinned than Central Africans, and southern Europeans are generally lighter-skinned than North Africans. In turn, northern Italians are generally lighter-skinned than Sicilians, and the Irish, Danes, and Swedes are generally lighter-skinned than northern Italians and Hungarians. Thus, human skin color cannot be used as a definitive marker of racial boundaries because it is not a discrete static trait. There are a few notable exceptions to this general rule of lighter-complexioned people inhabiting northern latitudes.

Vitamin D and Skin Color

The Chukchi of Eastern Siberia and Inuits of Alaska, Canada, and Greenland have darker skin than other Eurasian people living at similar latitudes, such as Scandinavians. Physical anthropologists have explained this exception in terms of the distinct dietary customs of indigenous Arctic groups, which have traditionally been based on certain native meats and fish that are rich in Vitamin D (polar bears, whales, seals, and trout). So, what does Vitamin D have to do with skin color? The answer is intriguing! Dark skin blocks most of the sun’s dangerous ultraviolet rays, which is advantageous in tropical environments where sunlight is most intense. Exposure to high levels of ultraviolet radiation can damage skin cells, causing cancer, and also destroy the body’s supply of folate, a nutrient essential for reproduction. Folate deficiency in women can cause severe birth

defects in their babies. Melanin, the pigment produced in skin cells, acts as a natural sunblock, protecting skin cells from damage, and preventing the breakdown of folate. However, exposure to sunlight has an important positive health effect: stimulating the production of vitamin D.

Vitamin D is essential for the health of bones and the immune system. In areas where ultraviolet radiation is strong, there is no problem producing enough Vitamin D, even as darker skin filters ultraviolet radiation.[7] In environments where the sun’s rays are much less intense, a different problem occurs: not enough sunlight penetrates the skin to enable the production of Vitamin D. Over the course of human evolution, natural selection favored the evolution of lighter skin as humans migrated and settled farther from the equator to ensure that weaker rays of sunlight could adequately penetrate our skin. The diet of indigenous populations of the Arctic region provided sufficient amounts of Vitamin D to ensure their health. This reduced the selective pressure toward the evolution of lighter skin among the Inuit and the Chukchi. Physical anthropologist Nina Jablonski (2012) has also noted that natural selection could have favored darker skin in Arctic regions because high levels of ultraviolet radiation from the sun are reflected from snow and ice during the summer months.

Still, many people in the United States remain convinced that biologically distinct human races exist and are easy to identify, declaring that they can walk down any street in the United States and easily determine who is “white” and who is “Black.” United States history gives us a hint as to why. The United States was populated historically by immigrants from a small number of world regions who did not reflect the full spectrum of human physical variation. The earliest settlers in the North American colonies overwhelmingly came from Northern Europe (particularly, Britain, France, Germany, and Ireland), regions where skin colors tend to be among the lightest in the world. Slaves brought to the United States during the colonial period came largely from the western coast of Central Africa, a region where skin color tends to be among the darkest in the world. Consequently, when we look at today’s descendants of these groups, we are not looking at accurate, proportional representations of the total range of human skin color; instead, we are looking, in effect, at opposite ends of a spectrum, where striking differences are inevitable. More recent waves of immigrants who have come to the United States from other world regions have brought a wider range of skin colors, shaping a continuum of skin color that defies classification into a few simple categories. Even with more human variation, the reification of race has made it challenging to ensure the public has an accurate understanding of race.

Physical anthropologists have also found that there are no specific genetic traits that are exclusive to a “racial” group. For the concept of human races to have biological significance, an analysis of multiple genetic traits would have to consistently produce the same racial classifications. In other words, a racial classification scheme for skin color would also have to reflect classifications by blood type, hair texture, eye shape, lactose intolerance, and other traits often mistakenly assumed to be “racial” characteristics. An analysis based on any one of those characteristics individually would produce a unique set of racial categories because variations in human physical and genetic traits are nonconcordant. Each trait is inherited independently, not “bundled together” with other traits and inherited as a package. There is no correlation between skin color and other characteristics such as blood type and lactose intolerance.

Non Concordance: The Sickle Cell Example

A prominent example of non concordance is sickle-cell anemia, which people often mistakenly think of as a disease that only affects Africans, African Americans, and Black persons. In fact, the sickle-cell allele (the version of the gene that causes sickle-cell anemia when a person inherits two copies) is relatively common among people whose ancestors are from regions where a certain strain of malaria, plasmodium falciparum, is prevalent, namely Central and Western Africa and parts of Mediterranean Europe, the Arabian peninsula, and India. The sickle-cell trait thus is not exclusively African or Black. The erroneous perceptions are related primarily to the fact that the ancestors of U.S. African Americans came predominantly from Western Africa, where the sickle-cell gene is prevalent, and are therefore more recognizable than populations of other ancestries and regions where the sickle-cell gene is common, such as southern Europe and Arabia.[8]

Another trait commonly mistaken as defining race is the epicanthic eye fold typically associated with people of East Asian ancestry. The epicanthic eye fold at the outer corner of the eyelid produces the eye shape that people in the United States typically associate with people from China and Japan but is also common in people from Central Asia, parts of Eastern Europe, and Scandinavia, some American Indian groups, and the KhoiSan of southern Africa.

In college, Justin took a course titled “Nutrition” because I thought it would be an easy way to boost my grade point average. The professor of the class, an authoritarian man in his late 60s or early 70s, routinely declared that “Asians can’t drink milk!” When this assertion was challenged by various students, including a woman who claimed that her best friend was Korean and drank milk and ate ice cream all the time, the professor only became more strident, doubling down on his dairy diatribe and defiantly vowing that he would not “ignore the facts” for “purposes of political correctness. There is a larger percentage of Asian people that are lactose intolerant but that does not mean that “Asians can’t drink milk”. In this story, students showed knowledge and advocacy in speaking up to the professor about an incorrect racist assumption about Asian people. Instead of taking a step back and reassessing their knowledge, this professor continued using his authority to present inaccurate and racist information.

Lactose tolerance is a complex topic. Lactose is a sugar that is naturally present in milk and dairy products, and an enzyme, lactase, breaks it down into two simpler sugars that can be digested by the body. Ordinarily, humans (and other mammals) stop producing lactase after infancy, and approximately 75 percent of humans are thus lactose intolerant and cannot naturally digest milk. Lactose intolerance is a natural, normal condition. However, some people continue to produce lactase into adulthood and can naturally digest milk and dairy products. This lactose persistence developed through natural selection, primarily among people in regions that had long histories of dairy farming (including the Middle East, Northern Europe, Eastern Europe, East Africa, and Northern India). In other areas and for some groups of people, dairy products were introduced relatively recently (such as East Asia, Southern Europe, and Western and Southern Africa and among Australian Aborigines and American Indians) and lactose persistence has not developed yet.[9]

How Different are We?

The idea of biological human races emphasizes differences, both real and perceived, between groups and ignores or overlooks differences within groups. The biological differences between arbitrary racial groups, i.e., between whites and Blacks or between Blacks and Asians, are assumed to be greater than the biological differences within “race” categories, i.e., within everyone considered “white.” THIS IS NOT TRUE. The opposite is actually true; the overwhelming majority of genetic diversity in humans (88–92 percent) is found within people who live on the same continent and who are seen as belonging to a particular “race.”[10]

So how do we compare to other species? Are we more genetically different as we seem to think or more genetically similar? Human beings are one of the most genetically similar of all species. There is nearly six times more genetic variation among white-tailed deer in the southern United States than in all humans! Consider our closest living relative, the chimpanzee. Chimpanzees’ natural habitat is confined to central Africa and parts of western Africa, yet four genetically distinct groups occupy those regions and they are far more genetically distinct than humans who live on different continents.

That humans exhibit such a low level of genetic variation compared to other species reflects the fact that we are a relatively recent species that originated from one location; modern humans (Homo sapiens) first appeared in East Africa just under 200,000 years ago.[11]

What does it mean to say that genetic variation is greater within so-called "races" than when we look at two different "races"? Question of Brendan Kavanah, HCC student in Fall 2023 Cultural Anthropology course.

If I were to try to explain it to someone else who has an understanding of biology similar to my own, I'd use the following example: "Imagine you have Liam and Emma. They're both what you'd call white, if you were placing them using a spectrum of paint swatches. Let's even say they're both 3rd generation Italians from South Orange, NJ. Imagine we run 500 tests about their genetic makeup: To what diseases are their immune systems most resistant, to what chemicals are they most likely to have extra-sensitive olfactory or taste sensitivity, what has been the average height of the last 10 generations of each's paternal family tree? We compare the values from Liam and Emma against each other for each question, and assign values to the differences to get a numeric representation of the relative genetic variety between the two people. They might have had very different answers for each question, meaning that relatively there's a lot of differences between their genes, but overall the answers will likely be inside of the average range for human beings thus far in our evolution. Then you have Ahmed, for comparison. He is from Alexandria, Egypt, and his skin is far darker than Liam’s or Emma’s. If you were to run that same 500-test routine on him, but also all the other people in his neighborhood, you'd find that Ahmed's values fall right into the middle of the spectrum of each test when comparing him and all of his neighbors together. He's the most average guy around, genetically speaking. If you were to then compare the values for Ahmed in these tests against those of Liam and Emma, you'd be likely to find that the values representing Ahmed's (statistically average, but geographically foreign) genetic makeup fall consistently within the spectrums established by comparing Liam and Emma's genetic variety. In this way, it could be seen that there is more genetic variety between the two white sample individuals than any averaged representative of a different race or ethnic group."

9.3.2 A Challenge to Racial Thinking: Anthropologist Franz Boas

Physical anthropologists today analyze human biological variation by examining specific genetic traits to understand how those traits originated and evolved over time and why some genetic traits are more common in certain populations. Since much of our biological diversity occurs mostly within (rather than between) continental regions once believed to be the homelands of distinct races, the concept of race is meaningless in any study of human biology. Franz Boas, considered the father of modern U.S. anthropology, was the first prominent anthropologist to challenge racial thinking directly during the early twentieth century. A professor of anthropology at Columbia University in New York City and a Jewish immigrant from Germany, Boas established anthropology in the United States as a four-field academic discipline consisting of archaeology, physical/biological anthropology, cultural anthropology, and linguistics.

His approach challenged the conventional thinking at the time that humans could be separated into biological races endowed with unique intellectual, moral, and physical abilities. In one of his most famous studies, Boas challenged craniometrics, in which the size and shape of skulls of various groups were measured as a way of assigning relative intelligence and moral behavior. Boas noted that the size and shape of the skull were not fixed characteristics within groups and were instead influenced by the environment. Children born in the United States to parents of various immigrant groups, for example, had slightly different average skull shapes than children born and raised in the homelands of those immigrant groups. The differences reflected relative access to nutrition and other socio-economic dimensions. In his famous 1909 essay “Race Problems in America,” Boas challenged the commonly held idea that immigrants to the United States from Italy, Poland, Russia, Greece, the Austro-Hungarian Empire, and other southern and eastern European nations were a threat to America’s “racial purity.” He pointed out that the British, Germans, and Scandinavians (popularly believed at the time to be the “true white” heritages that gave the United States its superior qualities) were not themselves “racially pure.” Instead, many different tribal and cultural groups had intermixed over the centuries. In fact, Boas asserted, the notion of “racial purity” was utter nonsense. As present-day anthropologist Jonathan Marks (1994) noted, “You may group humans into a small number of races if you want to, but you are denied biology as a support for it.”[12]

Quick reading check: Explain the concept of skin color as an example of clinal variation. [Note: the term discredited here means that it is no longer respected as scientific fact.]

Extra Information on The Problem with Race as Biology: For my science students in the class and others who might be interested, please review Nina Jablonski's work here - https://www.biointeractive.org/classroom-resources/biology-skin-color - the site includes an 18 min video along with other content you might be interested in regarding human skin color.