9.2 “Dude, What Are You?!”

A story that sounds familiar: Justin García

Ordinarily, students select a college major or minor by carefully considering their personal interests, particular subjects that pique their curiosity and fields they feel would be a good basis for future professional careers. Technically, my decision to major in anthropology and later earn a master’s degree and doctorate in anthropology was mine alone, but I tell my friends and students, only partly as a joke, that my choice of major was made for me to some degree by people I encountered as a child, teenager, and young adult. Since middle school, I had noticed that many people—complete strangers, classmates, coworkers, and friends—seemed to find my physical appearance confusing or abnormal, often leading them to ask me questions like “What are you?” and “What’s your race?” Others simply assumed my heritage as if it was self-evident and easily defined and then interacted with me according to their conclusions.

These subjective determinations varied wildly from person to person and from situation to situation. I distinctly recall, for example, an incident in a souvenir shop at the beach in Ocean City, Maryland, shortly after I graduated from high school. A middle-aged merchant attempted to persuade me to purchase a T-shirt that boldly declared “100% Italian . . . and “Proud of It!” with bubbled letters that spelled “Italian” shaded green, white, and red. Despite my repeated efforts to convince the merchant that I was not of Italian ethnic heritage, he refused to believe me. On another occasion during my mid-twenties while I was studying for my doctoral degree at Temple University, I was walking down Diamond Street in North Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, passing through a predominantly African American neighborhood. As I passed a group of six male teenagers socializing on the steps of a row house, one of them shouted “Hey, honky! What are you doing in this neighborhood?” Somewhat startled at being labeled a “honky,” (something I had never been called before), I looked at the group and erupted in laughter, which produced looks of surprise and disbelief in return. As I proceeded to walk a few more blocks and reached the predominantly Puerto Rican neighborhood of Lower Kensington, three young women flirtatiously addressed me as papí (an affectionate Spanish slang term for man). My transformation from “honky” to “papí” in a span of ten minutes spoke volumes about my life history and social experiences—and sparked my interest in cultural and physical anthropology.

Throughout my life, my physical appearance has provided me with countless unique and memorable experiences that have emphasized the significance of race and ethnicity as socially constructed concepts in America and other societies. My fascination with this subject is therefore both personal and professional; a lifetime of questions and assumptions from others regarding my racial and ethnic background have cultivated my interest in these topics. I noticed that my perceived race or ethnicity, much like beauty, rested in the eye of the beholder as individuals in different regions of the country (and outside of the United States) often perceived me as having different specific heritages. For example, as a teenager living in York County, Pennsylvania, senior citizens and middle-aged individuals usually assumed I was “white”, while younger residents often saw me as Puerto Rican or generically Hispanic or Latino. When I lived in Philadelphia, locals mostly assumed I was Italian American, but many Puerto Ricans, Mexicans, and Dominicans in the City of Brotherly Love often took me for either Puerto Rican or Cuban.

My experiences in the southwest were a different matter altogether. During my time in Texas, New Mexico, and Colorado, local residents—regardless of their respective heritages—commonly assumed I was of Mexican descent. At times, local Mexican Americans addressed me as carnal (pronounced CAR nowl), a term often used to imply a strong sense of community among Mexican American men that is somewhat akin to frequent use of the label “brother” among African American men. On more occasions than I can count, people assumed that I spoke Spanish. Once, in Los Angeles, someone from the Spanish-language television network Univisión attempted to interview me about my thoughts on an immigration bill pending in the California legislature. My West Coast friends and professional colleagues were surprised to hear that I was usually assumed to be Puerto Rican, Italian, or simply “white” on the East Coast, and one of my closest friends from graduate school—a Mexican American woman from northern California—once memorably stated that she would not even assume that I was half white.

I have a rather ambiguous physical appearance—a shaved head, brown eyes, and a black mustache and goatee. Depending on who one asks, I have either a “pasty white” or “somewhat olive” complexion, and my last name is often the single biggest factor that leads people on the East Coast to conclude that I am Puerto Rican.

When I (Vanessa) first read Justin´s story, I felt seen because his experience was so much like mine, except for the variation of gender. As a Boricua with light skin, my ambiguous racial look meant that my lived experience was one of passing for white, but only sometimes. Some people assumed I was Italian or Greek while others would make racist comments in my presence, finding out after I responded in anger, that I was not ¨white¨ like them. In my 20s, I was working as an Assistant Director at a Girl Scout Camp in Western Massachusetts, an area known for being tolerant of difference and assumed to be without racism. Another Latina camp counselor and I were talking in Spanish with some Latinx youth from Holyoke attending the camp when we were approached by a monolingual white camp counselor. She turned to me and asked how I knew Spanish. When I responded that Spanish was my native language and that I was Puerto Rican, she said ¨No, you are not.” When I persisted in my assertion that I was in fact Puerto Rican, she doubled down insisting that I could not be. What she was trying to communicate, albeit poorly, was that she could not understand how I could be Puerto Rican because I looked so ¨white¨. The Latinx youth responded in Spanish asking me what she meant. The kids were upset that someone was trying to deny my identity. Unfortunately, this was not the first time I had seen disbelief in response to my assertion of my latinidad. I had to get the Director involved to address the issue as I was concerned about this counselor’s ability to work with óur youth of color.

My ambiguous skin ensures that individuals not well versed in U.S. history and global issues make uninformed comments about race. It also means that when I teach this chapter in my classes, I spend a lot of time working with student’s preconceived notions about race to get them to understand that racism and privilege are the critical reasons we need to better understand and address race issues.

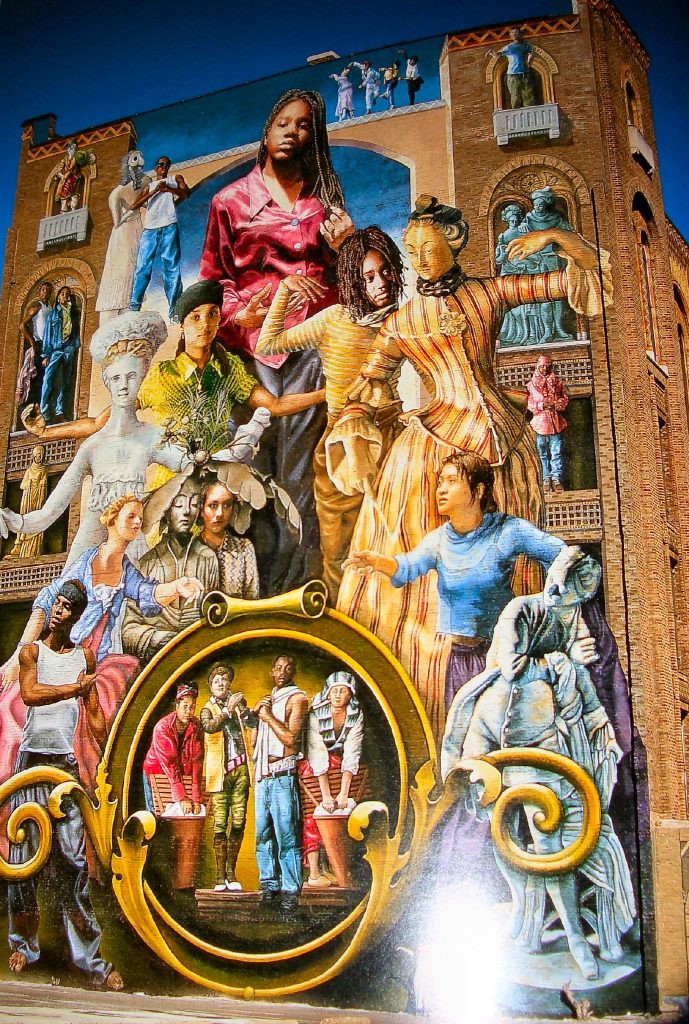

The Common Threads mural at Broad and Spring Garden Streets in Philadelphia, PA highlights the cultural diversity of the city.

Justin’s and my experiences are examples of what sociologists Michael Omi and Howard Winant (1986) referred to as “racial commonsense”—a deeply entrenched social belief that another person’s racial or ethnic background is obvious and easily determined from brief glances and can be used to predict a person’s culture, behavior, and personality. Reality, of course, is far more complex. One’s racial or ethnic background cannot necessarily be accurately determined based on physical appearance alone, and an individual’s “race” does not necessarily determine his or her “culture,” which in turn does not determine “personality.” Yet, these perceptions remain.

Quick Reading Check: Fix the incorrect statements below.

- Race is determined by your physical traits.

- Race tells us everything we need to know about your culture.

- Race is socially and biologically constructed.

Media Attributions

- The Common Threads Mural © Mike Graham! via. Flickr adapted by https://www.flickr.com is licensed under a CC BY (Attribution) license

a concept developed by society that is maintained over time through social interactions that make the idea seem “real.”