7.3 Ranked Societies and Chiefdoms

Unlike egalitarian societies, ranked societies (sometimes called “rank societies”) involve greater differentiation between individuals and the kin groups to which they belong. These differences can be, and often are, inherited, but there are no significant restrictions in these societies on access to basic resources. All individuals can meet their basic needs. The most important differences between people of different ranks are based on sumptuary rules—norms that permit persons of higher rank to enjoy greater social status by wearing distinctive clothing, jewelry, and/or decorations denied those of lower rank. Every family group or lineage in the community is ranked in a hierarchy of prestige and power. Furthermore, within families, siblings are ranked by birth order and villages can also be ranked.

The concept of a ranked society leads us directly to the characteristics of chiefdoms. Unlike the position of headman in a band, the position of chief is an office—a permanent political status that demands a successor when the current chief dies. There are, therefore, two concepts of chief: the man (women rarely, if ever, occupy these posts) and the office. Thus the expression “The king is dead, long live the king.” With the New Guinean big man, there is no formal succession. Other big men will be recognized and eventually take the place of one who dies, but there is no rule stipulating that his eldest son or any son must succeed him. For chiefs, there must be a successor and there are rules of succession.

Political chiefdoms usually are accompanied by an economic exchange system known as redistribution in which goods and services flow from the population at large to the central authority represented by the chief. It then becomes the task of the chief to return the flow of goods in another form. The chapter on economics provides additional information about redistribution economies.

These political and economic principles are exemplified by the potlatch custom of the Kwak- waka’wakw and other indigenous groups who lived in chiefdom societies along the northwest coast of North America from the extreme northwest tip of California through the coasts of Oregon, Washington, British Columbia, and southern Alaska. Potlatch ceremonies observed major events such as births, deaths, marriages of important persons, and installment of a new chief. Families prepared for the event by collecting food and other valuables such as fish, berries, blankets, animal skins, carved boxes, and copper. At the potlatch, several ceremonies were held, dances were performed by their “owners,” and speeches were delivered. The new chief was watched very carefully. Members of the society noted the eloquence of his speech, the grace of his presence, and any mistakes he made, however egregious or trivial. Next came the distribution of gifts, and again the chief was observed. Was he generous with his gifts? Was the value of his gifts appropriate to the rank of the recipient or did he give valuable presents to individuals of relatively low rank? Did his wealth allow him to offer valuable objects?

The next phase of the potlatch was critical to the chief’s validation of his position. Visitor after visitor would arise and give long speeches evaluating the worthiness of this successor to the chieftainship of his father. If his performance had so far met their expectations, and if his gifts were appropriate, the guests’ speeches praised him accordingly. They were less than adulatory if the chief had not performed to their expectations and they deemed the formal eligibility of the successor insufficient. He had to perform. If he did, then the guests’ praise not only legitimized the new chief in his role, but also ensured some measure of peace between villages. Thus, in addition to being a festive event, the potlatch determined the successor’s legitimacy and served as a form of diplomacy between groups.[1]

Much has been made among anthropologists of rivalry potlatches in which competitive gifts were given by rival pretenders to the chieftainship. Philip Drucker argued that competitive potlatches were a product of sudden demographic changes among the indigenous groups on the northwest coast.[2] When smallpox and other diseases decimated hundreds, many potential successors to the chieftainship died, leading to situations in which several potential successors might be eligible for the chieftainship. Thus, competition in potlatch ceremonies became extreme with blankets or copper repaid with ever- larger piles and competitors who destroyed their own valuables to demonstrate their wealth. The events became so raucous that the Canadian government outlawed the displays in the early part of the twentieth century.[3] Prior to that time, it had been sufficient for a successor who was chosen beforehand to present appropriate gifts.[4]

Quick Reading Check: Describe two differences between chiefdoms and tribal societies.

7.3.1 Integration through Marriage

Because chiefdoms cannot enforce their power by controlling resources or by having a monopoly on the use of force, they rely on integrative mechanisms that cut across kinship groups. As with tribal societies, marriage provides chiefdoms with a framework for encouraging social cohesion. However, since chiefdoms have more-elaborate status hierarchies than tribes, marriages tend to reinforce ranks.

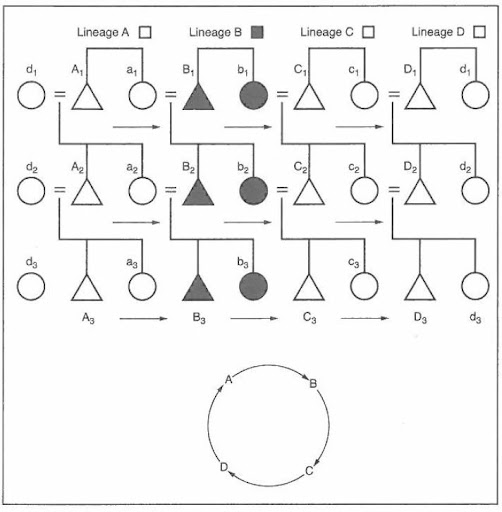

A particular kind of marriage known as matrilateral cross-cousin demonstrates this effect and is illustrated by the diagram in Figure 4. The figure shows three patrilineages (family lineage groups based on descent from a common male ancestor) that are labeled A, B, and C. Consider the marriage between man B2 and woman a2. As you can see, they are linked by B1 (ego’s father) and his sister (a2), who is married to A1 and bears daughter a2. If you look at other partners, you will notice that all of the women move to the right: a2 and B2’s daughter, b3, will marry C3 and bear a daughter, c4.

Viewed from the top of a flow diagram, the three lineages marry in a circle and at least three lineages are needed for this arrangement to work. The Purum of India, for example, practiced matrilateral cross-cousin marriage among seven lineages. Notice that lineage B cannot return the gift of A’s daughter with one of its own. If A2 married B2, he would be marrying his patrilateral cross-cousin who is linked to him through A1, his sister a1, and her daughter b2. Therefore, b2 must marry C2 and lineage B can never repay lineage A for the loss of their daughters—trace their links to find out why. Since lineage B cannot meet the third of Mauss’ obligations. B is a beggar relative to A. And lineage C is a beggar relative to lineage B. Paradoxically, lineage A (which gives its daughters to B) owes lineage C because it obtains its brides from lineage C. In this system, there appears to be an equality of inequality.

The patrilineal cross-cousin marriage system also operates in a complex society in highland Burma known as the Kachin. In that system, the wife-giving lineage is known as mayu and the wife-receiving lineage as dama to the lineage that gave it a wife. Thus, in addition to other mechanisms of dominance, higher-ranked lineages maintain their superiority by giving daughters to lower-ranked lineages and reinforce the relations between social classes through the mayu-dama relationship.[5]

The Kachin are not alone in using interclass marriage to reinforce dominance. The Natchez peoples, a matrilineal society of the Mississippi region of North America, were divided into four classes: Great Sun chiefs, noble lineages, honored lineages, and inferior “stinkards” (commoners). Unlike the Kachin, however, their marriage system was a way to upward mobility. The child of a woman who married a man of lower status assumed his/her mother’s status. Thus, if a Great Sun woman married a stinkard (commoner), the child would become a Great Sun. If a stinkard man were to marry a Great Sun woman, the child would be the same rank as the mother. The same relationship obtained between women of noble lineage and honored lineage and men of lower status. Only two stinkard partners would maintain that stratum, which was continuously replenished with people in warfare.[6]

Other societies maintained status in different ways. Brother-sister marriages, for example, were common in the royal lineages of the Inca, the Ancient Egyptians, and the Hawaiians, which sought to keep their lineages “pure.” Another, more-common type was patrilateral parallel-cousin marriage in which men married their fathers’ brothers’ daughters. This marriage system, which operated among many Middle Eastern nomadic societies, including the Rwala Bedouin chiefdoms, consolidated their herds, an important consideration for lineages wishing to maintain their wealth.[7]

7.3.2 Integration Through Secret Societies

Poro and sande secret societies for men and women, respectively, are found in the Mande-speaking peoples of West Africa, particularly in Liberia, Sierra Leone, the Ivory Coast, and Guinea. The societies are illegal under Guinea’s national laws. Outside of Guinea, they are legal and membership is universally mandatory under local laws. These secret societies function in both political and religious sectors of society. So how can such societies be secret if all men and women must join? According to Beryl Bellman, who is a member of a poro association, the standard among the Kpelle of Liberia is an ability to keep secrets. Members of the community are entrusted with the political and religious responsibilities associated with the society only after they learn to keep secrets.[8] There are two political structures in poros and sandes: the “secular” and the “sacred.” The secular structure consists of the town chief, neighborhood and kin group headmen, and elders. The sacred structure (the zo) is composed of a hierarchy of “priests” of the poro and the sande in the neighborhood, and among the Kpelle the poro and sande zo take turns dealing with in-town fighting, rapes, homicides, incest, and land disputes. They, like leopard skin chiefs, play an important role in mediation. The zo of both the poro and sande are held in great respect and even feared. Some authors have suggested that sacred structure strengthens the secular political authority because chiefs and landowners occupy the most powerful positions in the zo.[9] Consequently, these chiefdoms seem to have developed formative elements of a stratified society and a state, as we see in the next section.

Media Attributions

- Matrilateral cross cousin marriage © Kendall Hunt Publishing Company is licensed under a All Rights Reserved license

- Philip Drucker, Indians of the Northwest Coast (New York: Natural History Press, 1955). ↵

- Ibid ↵

- For more information about the reasons for the potlatch ban, see Douglas Cole and Ira Chaiken, An Iron Hand upon the People: The Law against the Potlatch on the Northwest Coast (Seattle: University of Washington Press, 1990). The website of the U’Mista Cultural Society in Alert Bay, British Columbia, Canada offers more information about potlatch traditions and the impact of the ban: www.umista.ca. ↵

- Philip Drucker, Indians of the Northwest Coast. ↵

- Edmund Leach, cited in Robin Fox, Kinship and Marriage, 215–216. ↵

- Raymond Scupin, Cultural Anthropology: A Global Perspective (Upper Saddle River, NJ: Pearson, 2012).4 ↵

- The information comes from William Lancaster, The Rwala Bedouin Today (Prospect Heights, IL: Waveland Press, 1997) and Elman Service, Profiles of Ethnology (New York: Harper Collins, 1978). ↵

- Beryl Bellman, The Language of Secrecy: Symbols and Metaphors in Poro Ritual (New Brunswick, NJ: Rutgers Uni- versity Press, 1984). ↵

- Kenneth Little, “The Political Function of the Poro, Part 1.” Africa 35 (1965):349–365. See also Caroline Bledsoe, Women and Marriage in Kpelle Society (Stanford: Stanford University Press, 1980). ↵

norms that permit persons of higher rank to enjoy greater social status by wearing distinctive clothing, jewelry, and/or decorations denied those of lower rank.

a man marries a woman who is his mother’s brother’s daughter. Matrilineal: kinship (family) systems that recognize only relatives through a line of female ancestors. Nation: an ethnic population.

kinship (family) systems that recognize only relatives through a line of male ancestors.

secret societies for men and women, respectively, found in the Mande-speaking peoples of West Africa, particularly in Liberia, Sierra Leone, the Ivory Coast, and Guinea.