6.3 Modes of Exchange

There are three distinct ways to integrate economic and social relations and distribute material goods. Contemporary economics only studies the first, market exchange. Most economic models are unable to explain the second two, reciprocity and redistribution, because they have different underlying logics. Economic anthropology, on the other hand, provides a rich and nuanced perspective into how diverse modes of exchange shape, and are shaped by, everyday life across space and time. Anthropologists understand market exchange to be a form of trade that today most commonly involves general purpose money, bargaining, and supply and demand price mechanisms. In contrast, reciprocity involves the exchange of goods and services and is rooted in a mutual sense of obligation and identity.

Anthropologists have identified three distinct types of reciprocity, which we will explore shortly: generalized, balanced, and negative.[1] Finally, redistribution occurs when an authority of some type (a temple priest, a chief, or even an institution such as the Internal Revenue Service) collects economic contributions from all community members and then redistributes these back in the form of goods and services. Redistribution requires centralized social organization, even if at a small scale (for example, within the foraging societies discussed above). As we will see, various modes of exchange can and do coexist, even within capitalism.

6.3.1 Reciprocity

While early economic anthropology often seemed focused on detailed investigations of seemingly exotic economic practices, anthropologists such as Bronislaw Malinowski and Marcel Mauss used ethnographic research and findings to critique Western, capitalist economic systems. Today, many follow in this tradition and some would agree with Keith Hart’s statement that economic anthropology “at its best has always been a search for an alternative to capitalism.”[2] Mauss, a French anthropologist, was one of the first scholars to provide an in-depth exploration of reciprocity and the role that gifts play in cultural systems around the world.[3] Mauss asked why humans feel obliged to reciprocate when they receive a gift. His answer was that giving and reciprocating gifts, whether these are material objects or our time, creates links between the people involved.[4]

Over the past century, anthropologists have devoted considerable attention to the topic of reciprocity. It is an attractive one because of the seemingly moral nature of gifts: many of us hope that humans are not solely self-interested, antisocial economic actors. Gifts are about social relations, not just about the gifts themselves; as we will see, giving a gift that contains a bit of oneself builds a social relationship with the person who receives it.[5] Studying reciprocity gives anthropologists unique insights into the moral economy, or the processes through which customs, cultural values, beliefs, and social coercion influence our economic behavior. The economy can be understood as a symbolic reflection of the cultural order and the sense of right and wrong that people adhere to within that cultural order.[6] This means that economic behavior is a unique cultural practice, one that varies across time and space.

6.3.2 Generalized Reciprocity

Consider a young child. Friends and family members probably purchase numerous gifts for the child, small and large. People give freely of their time: changing diapers, cooking meals, driving the child to soccer practice, and tucking the child in at night. These myriad gifts of toys and time are not written down; we do not keep a running tally of everything we give our children. However, as children grow older they begin to reciprocate these gifts: mowing an elderly grandmother’s yard, cooking dinner for a parent who has to work late, or buying an expensive gift for an older sibling. When we gift without reckoning the exact value of the gift or expecting a specific thing in return we are practicing generalized reciprocity. This form of reciprocity occurs within the closest social relationships where exchange happens so frequently that monitoring the value of each item or service given and received would be impossible, and to do so would lead to tension and quite possibly the eventual dissolution of the relationship.

However, generalized reciprocity is not necessarily limited to households. In my own suburban Kentucky neighborhood we engage in many forms of generalized reciprocity. For example, we regularly cook and deliver meals for our neighbors who have a new baby, a sick parent, or recently deceased relative. Similarly, at Halloween we give out handfuls of candy (sometimes spending $50 or more in the process). I do not keep a close tally of which kid received which candy bar, nor do my young daughters pay close attention to which houses have more or less desirable candy this year. In other cultures, generalized reciprocity is the norm rather than the exception. Recall the Dobe Ju/’hoansi foragers who live in the Kalahari Desert: they have a flexible and overlapping kinship system which ensures that the products of their hunting and gathering are shared widely across the entire community. This generalized reciprocity reinforces the solidarity of the group; however, it also means that Dobe Ju/’hoansi have very few individual possessions and generosity is a prized personality trait.

6.3.3 Balanced Reciprocity

Unlike generalized reciprocity, balanced reciprocity is more of a direct exchange in which something is traded or given with the expectation that something of equal value will be returned within a specific time period. This form of reciprocity involves three distinct stages: the gift must be given, it has to be received, and a reciprocal gift has to be returned. A key aspect of balanced reciprocity is that without reciprocation within an appropriate time frame, the exchange system will falter and the social relationship might end. Balanced reciprocity generally occurs at a social level more distant than the family, but it usually occurs among people who know each other. In other words, complete strangers would be unlikely to engage in balanced reciprocity because they would not be able to trust the person to reciprocate within an acceptable period of time.

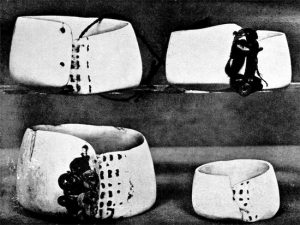

The Kula ring system of exchange found in the Trobriand Islands in the South Pacific is one example of balanced reciprocity. A Kula ring involves the ceremonial exchange of shell and bead necklaces (soulava) for shell arm bands (mwali) between trading partners living on different islands. The arm bands and necklaces constantly circulate and only have symbolic value, meaning they bring the temporary owner honor and prestige but cannot be bought or sold for money. Malinowski was the first anthropologist to study the Kula ring, and he found that although participants did not profit materially from the exchange, it served several important functions in Trobriand society.[7] Since participants formed relationships with trading participants on other islands, the Kula ring helped solidify alliances among tribes, and overseas partners became allies in a land of danger and insecurity. Along with armbands and necklaces, Kula participants were also engaging in more mundane forms of trade, bartering from one island to another. Additionally, songs, customs, and cultural influences also traveled along the Kula route. Finally, although ownership of the armbands and necklaces was always temporary (for eventually participants are expected to give the items to other partners in the ring), Kula participants took great pride and pleasure in the items they received. The Kula ring exhibits all the hallmarks of balanced reciprocity: necklaces are traded for armbands with the expectation that objects of equal value will be returned within a specific time period.

The Work of Reciprocity at Christmas

How many of us give and receive gifts during the holiday season? Christmas is undeniably a religious celebration, yet while nine in ten Americans say they celebrate Christmas, about half view it to be more of a secular holiday. Perhaps this is why eight in ten non-Christians in the United States now celebrate Christmas.[8] How and why has this one date in the liturgical calendar come to be so central to U.S. culture and what does gift giving have to do with it? In 1865, Christmas was declared a national holiday; just 25 years later, Ladies’ Home Journal was already complaining that the holiday had become overly commercialized.[9] A recent survey of U.S. citizens found that we continue to be frustrated with the commercialization of the season: one-third say they dislike the materialism of the holidays, one-fifth are unhappy with the expenses of the season, and one in ten dislikes holiday shopping in crowded malls and stores.[10]

When asked what they like most about the holiday season, 70 percent of U.S. residents say spending time with family and friends. This raises the question of how and why reciprocal gift giving has become so central to the social relationships we hope to nurture at Christmas. The anthropologist James Carrier argues that the affectionate giving at the heart of modern Christmas is in fact a celebration of personal social relations.[11] Among our family members and closest friends this gift giving is generalized and more about the expression of sentiment. When we exchange gifts with those outside this small circle it tends to be more balanced, and we expect some form of equivalent reciprocation. If I spend $50 on a lavish gift for a friend, my feelings will undoubtedly be hurt when she reciprocates with a $5 gift card to Starbucks.

Christmas shopping is arduous–we probably all know someone who heads to the stores at midnight on Black Friday to get a jumpstart on their consumption. Throughout the month of December we complain about how crowded the stores are and how tired we are of wrapping presents. Let’s face it: Christmas is a lot of work! Recall how the reciprocity of the Kula ring served many functions in addition to the simple exchange of symbolic arm bands and shell necklaces. Similarly, Christmas gift giving is about more than exchanging commodities. In order to cement our social relationships we buy and wrap gifts (even figuratively by placing a giant red bow on oversize items like a new bicycle) in order to symbolically transform the impersonal commodities that populate our everyday lives into meaningful gifts. The ritual of shopping, wrapping, giving, and receiving proves to us that we can create a sphere of love and intimacy alongside the world of anonymous, monetary exchange. The ritualistic exchange of gifts is accompanied by other traditions, such as the circulation of holiday cards that have no economic or practical value, but instead are used to reinforce social relationships. When we view Christmas through a moral economic lens, we come to understand how our economic behavior is shaped by our historical customs, cultural values, beliefs, and even our need to maintain appearances. Christmas is hard work, but with any luck we will reap the rewards of strong relational bonds.[12]

6.3.4 Negative Reciprocity

Unlike balanced and generalized reciprocity, negative reciprocity is an attempt to get something for nothing. It is the most impersonal of the three forms of reciprocity and it commonly exists among people who do not know each other well because close relationships are incompatible with attempts to take advantage of other people. Gambling is a good example of negative reciprocity, and some would argue that market exchange, in which one participant aims to buy low while the other aims to sell high, can also be a form of negative reciprocity.

The anthropologist Daniel Smith studied the motives and practices of Nigerian email scammers who are responsible for approximately one-fifth of these types of emails that flood Western inboxes.[13] He found that 419 scams, as they are known in Nigeria (after the section of the criminal code outlawing fraud), emerged in the largest African state (Nigeria has more than 130 million residents, nearly 70 percent of whom live below the poverty line) in the late 1990s when there were few legitimate economic opportunities for the large number of educated young people who had the English skills and technological expertise necessary for successful scams. Smith spoke with some of the Nigerians sending these emails and found that they dreamed of a big payoff someday. They reportedly felt bad for people who were duped, but said that if Americans were greedy enough to fall for it they got what they deserved.

The emails always begin with a friendly salutation: “Dear Beloved Friend, I know this message will come to you as a surprise but permit me of my desire to go into business relationship with you.” The introduction is often followed by a long involved story of deaths and unexpected inheritances: “I am Miss Naomi Surugaba, a daughter to late Al-badari Surugaba of Libya whom was murdered during the recent civil war in Libya in March 2011….my late Father came to Cotonou Benin republic with USD 4,200,000.00 (US$4.2M) which he deposited in a Bank here…for safekeeping. I am here seeking for an avenue to transfer the fund to you….Please I will offer you 20% of the total sum for your assistance…..”[14]

The emails are crafted to invoke a sense of balanced reciprocity: the authors tell us how trustworthy and esteemed we are and offer to give us a percentage of the money in exchange for our assistance. However, most savvy recipients immediately recognize that these scams are in fact a form of negative reciprocity since they know they will never actually receive the promised money and, in fact, will probably lose money if they give their bank account information to their correspondent.

The typical email correspondence always emphasizes the urgency, confidentiality, and reciprocity of the proposed arrangement. Smith argues that the 419 scams mimic long-standing cultural practices around kinship and patronage relations. While clearly 419 scammers are practicing negative reciprocity by trying to get something for nothing (unfortunately we will never receive the 20 percent of the $4.2 million that Miss Naomi Surugaba promised us), many in the United States continue to be lured in by the veneer of balanced reciprocity. The FBI receives an estimated 4,000 complaints about advance fee scams each year, and annual victim losses total over $55 million.[15]

Quick Reading Check: How does reciprocity work? What are the three forms and provide an example of each?

6.3.5 Redistribution

Redistribution is the accumulation of goods or labor by a particular person or institution for the purpose of dispersal at a later date. Redistribution is found in all societies. For example, within households we pool our labor and resources, yet we rarely distribute these outside of our family. For redistribution to become a central economic process, a society must have a centralized political apparatus to coordinate and enforce the practice.

Redistribution can occur alongside other forms of exchange. For example, in the United States everyone who works in the formal sector pays federal taxes to the Internal Revenue Service. During the 2015 fiscal year the IRS collected $3.3 trillion in federal revenue. It processed 243 million returns, and 119 million of these resulted in a tax refund. In total, $403.3 billion tax dollars were redistributed by this central political apparatus.[16] Even if I did not receive a cash refund from the IRS, I still benefited from the redistribution in the form of federal services and infrastructure.

Native American Potlatch: Reciprocity or Redistribution?

Sometimes economic practices that appear to be merely reciprocal gift exchanges are revealed to be forms of redistribution after closer inspection. The potlatch system of the Native American groups living in the United States and Canadian northwestern coastal area was long understood as an example of functional gift giving. Traditionally, two groups of clans would perform highly ritualized exchanges of food, blankets, and ritual objects. The system produced status and prestige among participants: by giving away more goods than another person, a chief could build his reputation and gain new respect within the community. After contact with settlers, the excessive gift giving during potlatches escalated to the point that early anthropologists described it as a “war of property.”[17]

Later anthropological studies of the potlatch revealed that rather than wasting, burning, or giving away their property to display their wealth, the groups were actually giving away goods that other groups could use and then waiting for a later potlatch when they would receive things not available in their own region. This was important because the availability of food hunted, fished, and foraged by native communities could be highly variable. The anthropologist Stuart Piddocke found that the potlatch primarily served a livelihood function by ensuring the redistribution of goods between groups with surpluses and those with deficits.[18] Our current understanding of the potlatch system shows how important it is to revisit research to ensure it is accurate and complete. Anthropology, as a discipline, continues to grow in knowledge and understanding of other cultures through its scholars’ self-reflection and humility in searching for the truth about humanity.

6.3.6 Markets

The third way that societies distribute goods and services is through market exchange. Markets are social institutions with prices or exchange equivalencies. Markets do not necessarily have to be localized in a geographic place (e.g., a marketplace), but they cannot exist without institutions to govern the exchanges. Market and reciprocal exchange appear to share similar features: one person gives something and the other receives something. A key distinction between the two is that market exchanges are regulated by supply and demand mechanisms. The forces of supply and demand can create risk for people living in societies that largely distribute goods through market exchange. If we lose our jobs, we may not be able to buy food for our families. In contrast, if a member of a Dobe Ju/’hoansi community is hurt and unable to gather foods today, she will continue to eat as a result of generalized reciprocal exchanges.

Market exchanges are based on transactions, or changes in the status of a good or service between people, such as a sale. While market exchange is generally less personal than reciprocal exchange, personalized transactions between people who have a relationship that endures beyond a single exchange do exist. Atomized transactions are impersonal ones between people who have no relationship with each other beyond the short term of the exchange. These are generally short-run, closed-ended transactions with few implications for the future. In contrast, personalized transactions occur between people who have a relationship that endures past the exchange and might include both social and economic elements. The transactors are embedded in networks of social relations and might even have knowledge of the other’s personality, family, or personal circumstances that helps them trust that the exchange will be satisfactory. Economic exchanges within families, for example when a child begins to work for a family business, are extreme examples of personalized market exchange.

To better understand the differences between transactions between relative strangers and those that are more personalized, consider the different options one has for a haircut: a person can stop by a chain salon such as Great Clips and leave twenty minutes later after spending $15 to have his hair trimmed by someone he has never met before, or he can develop an ongoing relationship with a hair stylist or barber he regularly visits. These appointments may last an hour or even longer, and he and his stylist probably chat about each other’s lives, the weather, or politics. At Christmas he may even bring a small gift or give an extra tip. He trusts his stylist to cut his hair the way he likes it because of their long history of personalized transactions.

6.3.8 Maine Lobster Markets

To better understand the nature of market transactions, anthropologist James Acheson studied the economic lives of Maine fishermen and lobster dealers.[19] The lobster market is highly sensitive to supply and demand: catch volumes and prices change radically over the course of the year. For example, during the winter months, lobster catches are typically low because the animals are inactive and fishermen are reluctant to go out into the cold and stormy seas for small catches. Beginning in April, lobsters become more active and, as the water warms, they migrate toward shore and catch volumes increase. In May prices fall dramatically; supply is high but there are relatively few tourists and demand is low. In June and July catch volume decreases again when lobsters molt and are difficult to catch, but demand increases due to the large influx of tourists, which, in turn, leads to higher prices. In the fall, after the tourists have left, catch volume increases again as a new class of recently molted lobsters become available to the fishermen. In other words, catch and price are inversely related: when the catch is lowest, the price is highest, and when the catch is highest, the price is lowest.

The fishermen generally sell their lobsters to wholesalers and have very little idea where the lobsters go, how many hands they pass through on their way to the consumer, how prices are set, or why they vary over the course of the year. In other words, from the fisherman’s point of view the process is shrouded in fog, mystery, and rumor. Acheson found that in order to manage the inherent risk posed by this variable market, fishermen form long-term, personalized economic relationships with particular dealers. The dealers’ goal is to ensure a large, steady supply of lobsters for as low a price as possible. In order to do so, they make contracts with fishermen to always buy all of the lobster they have to sell no matter how glutted the market might be. In exchange, the fishermen agree to sell their catches for the going rate and forfeit the right to bargain over price. The dealers provide added incentives to the fishermen: for example, they will allow fishermen to use their dock at no cost and supply them with gasoline, diesel fuel, paint, buoys, and gloves at cost or with only a small markup. They also often provide interest-free loans to their fishermen for boats, equipment, and traps. In sum, the Maine fishermen and the dealers have, over time, developed highly personalized exchange relations in order to manage the risky lobster market. While these market exchanges last over many seasons and rely on a certain degree of trust, neither the fishermen nor the dealers would characterize the relationship as reciprocal—they are buying and selling lobster, not exchanging gifts.

6.3.7 Money

While general purpose money is not a prerequisite for market exchanges, most commercial transactions today do involve the exchange of money. In our own society, and in most parts of the world, general purpose money can be exchanged for all manner of goods and services. General purpose money serves as a medium of exchange, a tool for storing wealth, and as a way to assign interchangeable values. It reflects our ideas about the generalized interchangeability of all things—it makes products and services from all over the world commensurable in terms of a single metric. In doing so, it increases opportunities for unequal exchange.[20] As we will see, different societies have attempted to challenge this notion of interchangeability and the inequalities it can foster in different ways.

| Guiding Principles | Key Features | Examples |

| Reciprocity (Balanced, Generalized, and Negative) | Reciprocity involves the exchange of goods and services and is rooted in a mutual sense of obligation and identity | -Birthday gift giving (Balanced)

-Kula Ring (Generalized) -Nigerian Email Scams (Negative) |

| Redistribution | Occurs when an authority (or institution) collects economic contributions from all the community members and then redistributes these back in a new form of goods and services | Potlatch

American Tax System |

| Market Exchange | a form of trade that today most commonly involves general purpose money, bargaining, and supply and demand price mechanisms | Capitalism

Haircut Trip to Target |

6.3.8 Tiv Spheres of Exchange

Prior to colonialism, the Tiv people in Nigeria had an economic system governed by a moral hierarchy of values that challenged the idea that all objects can be made commensurable through general purpose money. The anthropologists Paul and Laura Bohannan developed the theory of spheres of exchange after recognizing that the Tiv had three distinct economic arenas and that each arena had its own form of money.[21] The subsistence sphere included locally produced foods (yams, grains, and vegetables), chickens, goats, and household utensils. The second sphere encompassed slaves, cattle, white cloth, and metal bars. Finally, the third, most prestigious sphere was limited to marriageable females. Excluded completely from the Tiv spheres of exchange were labor (because it was always reciprocally exchanged) and land (which was not owned per se, but rather communally held within families).

The Tiv were able to convert their wealth upwards through the spheres of exchange. For example, a Tiv man could trade a portion of his yam harvest for slaves that, in turn, could be given as bridewealth for a marriageable female. However, it was considered immoral to convert wealth downwards: no honorable man would exchange slaves or brass rods for food.[22] The Bohannans found that this moral economy quickly collapsed when it was incorporated into the contemporary realm of general purpose money. When items in any of the three spheres could be exchanged for general purpose money, the Tiv could no longer maintain separate categories of exchangeable items. The Bohannans concluded that the moral meanings of money—in other words, how exchange is culturally conceived—can have very significant material implications for people’s everyday lives.[23]

Quick Reading Check: How has the adoption of general purpose money affected traditional spheres of exchange?

6.3.9 Local Currency Systems: Ithaca HOURS

While we may take our general purpose currency for granted, as the Tiv example demonstrates, money is profoundly symbolic and political. I.e. There is nothing “natural” about money. In fact, the reason we do not question its use is because we, Americans and other industrialized nations, are enculturated into not questioning our use of this “tool”. Money is not only the measure of value but also the purpose of much of our activity, and money shapes economic relations by creating inequalities and obliterating qualitative differences.[24] In other words, I might pay a babysitter $50 to watch my children for the evening, and I might spend $50 on a new sweater the next day. While these two expenses are commensurable through general purpose money, qualitatively they are in fact radically different in terms of the sentiment I attach to each (and I would not ever try to pay my babysitter in sweaters).

Some communities explicitly acknowledge the political and symbolic components of money and develop complementary currency systems with the goal of maximizing transactions in a geographically bounded area, such as within a single city. The goal is to encourage people to connect more directly with each other than they might do when shopping in corporate stores using general purpose money.[25] For example, the city of Ithaca, New York, promotes its local economy and community self-reliance through the use of Ithaca HOURS.[26] More than 900 participants accept Ithaca HOURS for goods and services, and some local employers and employees even pay or receive partial wages in the complementary currency. The currency has been in circulation since 1991, and the system was incorporated as a nonprofit organization in 1998. Today it is administered by a board of elected volunteers. Ithaca HOURS circulate in denominations of two, one, one-half, one-fourth, one-eighth, and one-tenth HOURS ($20, $10, $5, $2.50, $1.25, and $1, respectively). The HOURS are put into circulation through “disbursements” given to registered organization members, through small interest-free loans to local businesses, and through grants to community organizations. The name “HOURS” evokes the principle of labor exchange and the idea that a unit of time is equal for everyone.[27]

The anthropologist Faidra Papavasiliou studied the impact of the Ithaca HOURS currency system. She found that while the complementary currency does not necessarily create full economic equality, it does create deeper connections among community members and local businesses, helping to demystify and personalize exchange (much as we saw with the lobstermen and dealers). The Ithaca HOURS system also offers important networking opportunities for locally owned businesses and, because it provides zero interest business loans, it serves as a form of security against economic crisis.[28] Finally, the Ithaca HOURS complementary currency system encourages community members to shop at locally owned businesses. As we will see in the next section, where we choose to shop and what we choose to buy forms a large part of our lives and cultural identity. The HOURS system demonstrates a relatively successful approach to challenging the inequalities fostered by general purpose money.

Quick Reading Check: Can you think of two examples of inequalities that result from our dependence on general purpose money?

6.3.10 Local Currency: A Western Massachusetts Example

I, Brendan Kavanah, a Holyoke Community College ANT 101 student in Fall 2023, can actually provide a direct example of this from my own life. I grew up in Great Barrington, in Berkshire county, MA. There’s a local currency in the area called Berkshares that’s distributed at local banks and accepted at a few hundred businesses in the area, in order to encourage locals to spend their money locally, or to be more accurate, create a proportion of currency that can’t be spent outside of the local sphere. It costs $1 to get 1 Berkshare from a participating bank, but there’s a small exchange fee if trading them back in for regular US dollars, thereby encouraging users to hold onto them and guarantee that a local business will see the profit at some point. They’re usually given out at church events, community dinners, and as prizes for races or other contests. As I remember from when I was younger, this was especially true for events that were organized by local business owners like the garden supply store owner, and a few restaurant and brewery owners. Given that, on paper, Berkshares do nothing but limit the flexibility of a given dollar, the whole system can’t really function without a base of community-wide support. To help align with this idea of local pride, they even have designs that evoke the natural beauty of the region, and feature the faces of famous Berkshire residents on the front, like W.E.B. Du Bois, Norman Rockwell, and Robyn van En, who founded the first CSA in the US. Here’s the website: https://berkshares.org/ for more information.[29]

Quick Reading Check: Can you think of two examples of inequalities that result from our dependence on general purpose money?

Media Attributions

- Mwali © Sarah Lyon is licensed under a CC BY-NC-SA (Attribution NonCommercial ShareAlike) license

- In Ithica We Trust © Fllickr is licensed under a CC0 (Creative Commons Zero) license

- Marshall Sahlins, Stone Age Economics (Chicago: Aldine, 1972). ↵

- Keith Hart, “Money in Twentieth Century Anthropology,” 179. ↵

- Marcel Mauss, The Gift: The Form and Reason for Exchange in Archaic Societies (London: Routledge, 1990[1925]). ↵

- Richard Wilk and Lisa Cliggett, Economies and Cultures: Foundations of Economic Anthropology, 158. ↵

- Ibid., 162. ↵

- Ibid., 120. ↵

- Bronislaw Malinowski, Argonauts of the Western Pacific (New York: Dutton, 1961[1922]). ↵

- Pew Research Center, “Celebrating Christmas and the Holidays Then and Now,” December 18, 2013. http://www.pewforum.org/2013/12/18/celebrating-christmas-and-the-holidays-then-and-now/. ↵

- James Carrier, Gifts and Commodities: Exchange and Western Capitalism since 1700 (New York: Routledge, 1995), 189 ↵

- Pew Research Center, “Celebrating Christmas and the Holidays Then and Now.” ↵

- James Carrier, Gifts and Commodities. ↵

- Ibid., 178. ↵

- Daniel Smith, A Culture of Corruption: Everyday Deception and Popular Discontent in Nigeria (Princeton, NJ: Prince- ton University Press, 2007). ↵

- Erika Eichelberger, “What I Learned Hanging out with Nigerian Email Scammers,” Mother Jones, March 20, 2014. http://www.motherjones.com/politics/2014/03/what-i-learned-from-nigerian-scammers. ↵

- Erika Eichelberger, “What I Learned Hanging out with Nigerian Email Scammers.” ↵

- Internal Revenue Service, 2015 Data Book (Washington D.C. Internal Revenue Service, 2016). ↵

- Richard Wilk and Lisa Cliggett, Economies and Cultures,156. ↵

- Stuart Piddocke, “The Potlatch System of the Southern Kwakiutl: A New Perspective,” Southwestern Journal of Anthropology 21 (1965). ↵

- James Acheson, The Lobster Gangs of Maine (Lebanon, NH: University Press of New England, 1988). ↵

- Alf Hornborg, “Learning from the Tiv: Why a Sustainable Economy Would Have to Be ‘Multicentric,’” Culture and Agriculture 29 (2007): 64. ↵

- Paul Bohannan and Laura Bohannan, Tiv Economy (Evanston, IL: Northwestern University Press, 1968). ↵

- Paul Bohannan, “Some Principles of Exchange and Investment among the Tiv,” American Anthropologist 57 (1955): 65. ↵

- Ibid., 64. ↵

- Faidra Papavasiliou, “Fair Money, Fair Trade: Tracing Alternative Consumption in a Local Currency Economy,” in Fair Trade and Social Justice: Global Ethnographies, ed. Sarah Lyon and Mark Moberg (New York: New York University Press, 2010). ↵

- J. K. Gibson-Graham, Jenny Cameron, and Stephen Healy, Take Back the Economy: An Ethical Guide for Transforming Our Communities (Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press, 2013). ↵

- For more information, see http://ithacahours.info/ ↵

- Faidra Papavasiliou, “Fair Money, Fair Trade: Tracing Alternative Consumption in a Local Currency Economy.” ↵

- Ibid., 216. ↵

- Fall 2023 Holyoke Community College student Brendan Kavanah example of Berkshares currency. ↵

the accumulation of goods or labor by a particular person or institution for the purpose of dispersal at a later date.

giving without expecting a specific thing in return.

the exchange of something with the expectation that something of equal value will be returned within a specific time period.

an attempt to get something for nothing; exchange in which both parties try to take advantage of the other.

a medium of exchange that can be used in all economic transactions.