Reflect and Evaluate Culturally Responsive Practices

Reflective Practice Models

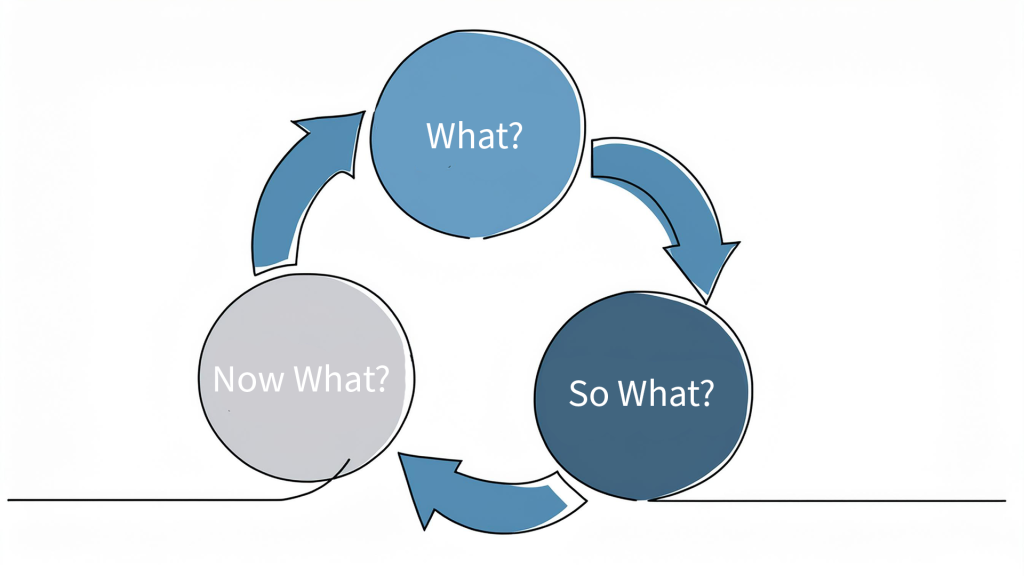

The simplest model of reflective practice is based on Kolb’s (1984) reflective practice cycle. This model guides the learner through identifying what happened, understanding why the outcome occurred, and planning for what to do next by asking the questions, What?, So what?, and Now what? This process can be done quickly and simply guides the reflective practitioner through identifying what they did, what happened as a result of what they did, and what they will do in the future to either change or replicate that outcome they got.

The Kolb model is a simple way to start reflective practice. What I find lacking about this model, though, is that there is not a step that engages the reflective practitioner to specifically identify how context impacted how one came to do what they did or how it affected the outcome. Early intervention has a complicated history and is built on the interactions of human beings who are emotional beings. We can’t separate the context in which we are doing our work, nor can we remove our feelings about it. For these reasons, I find that the Gibbs(1988) model of reflective practice is most appropriate for supporting reflections about the cultural responsiveness of our early intervention practices. This model can also be done independently or in conversation with a peer, or during reflective practice.

Gibbs’ Reflective Cycle

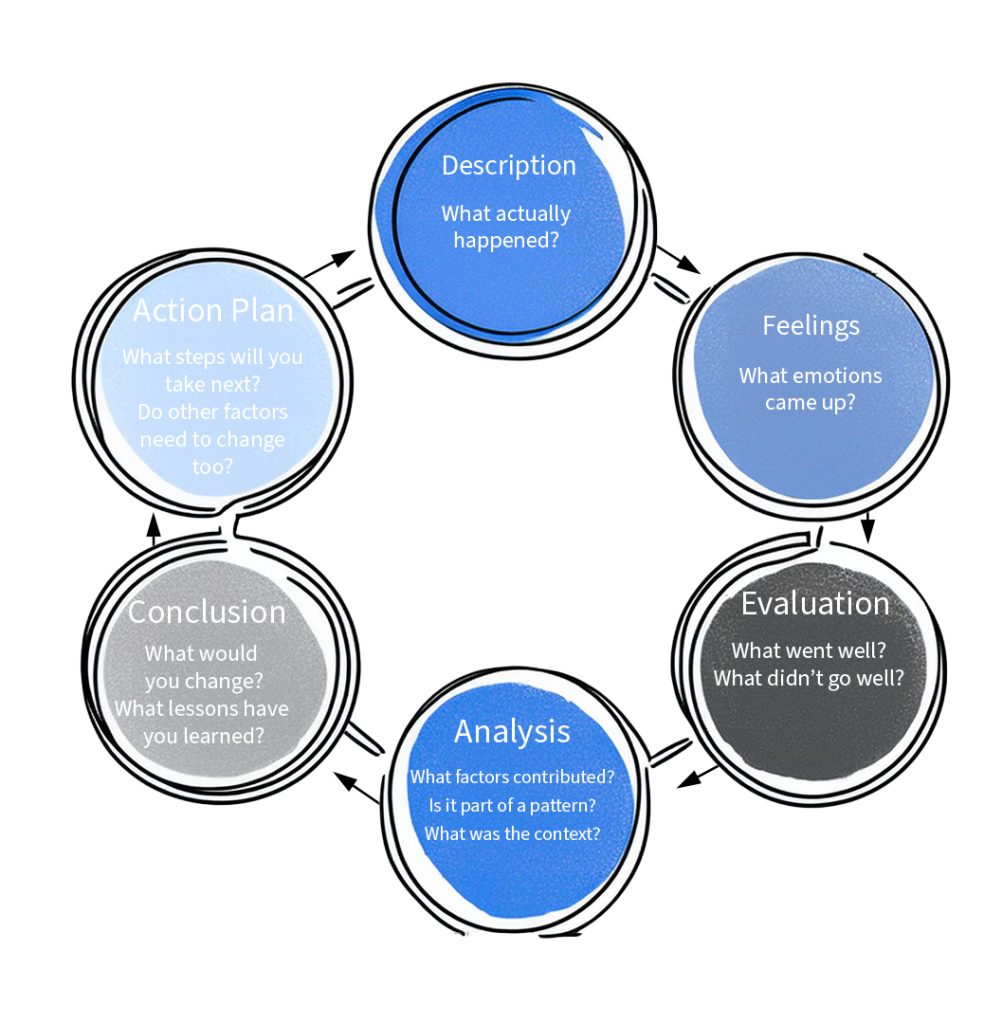

This model has six steps: Description, Feelings, Evaluation, Analysis, Conclusion, and Plan. The first step is to describe what happened, much like you would in the simplified reflective practice cycle.

Once you have described what happened, the second step is to name the emotions that everyone involved felt at the time and how they feel about it now. These emotions may be positive (joy, gratitude, pride, satisfaction, interest, inspiration, awe, relief) or negative (confusion, frustration, sadness, pain, fear, anger, shame, embarrassment, disgust), or a combination of the two. As you engage in step two, it’s key to not just name your emotions but also hone in on why you felt/feel those things. Our cultural and social identities impact how we process events and which emotions are acceptable for us to demonstrate. These identities also shape our values and ways of conceptualizing things like disability and help-giving, which then influence our emotions. Emotional reactions can be unexpected but always teach us something about ourselves and our relationship to what happened. I’ve found that in complicated situations I feel multiple emotions at once that can be hard to parse out. It may be helpful to you to use the the questions in the Challenging Interactions Reflective tool as a means to flush out all of the feelings you have about what happened. You may need to take time to process these emotions before you are ready to proceed with the reflective practice cycle.

After you have processed your feelings, the next step in Gibb’s cycle is to evaluate what happened by identifying what went well, what went poorly, what you did that went the way you intended, and what did not go the way you planned. This is also when you identify what other people involved in the situation did. I appreciate that this step asks learners to identify both what went well and what didn’t because rarely, in the course of an hour-long home visit, is everything perfect or terrible. In this step, we only name and describe the positive and negative actions. It’s not until step four, analysis, that we move into figuring out why and assigning meaning to what happened.

Once you’re ready for analysis, you should ask yourself questions about why this happened. When we’re doing work to be more culturally responsive, it will be helpful to consider the power dynamics, whether this is a part of a pattern of behavior, which of your values you were living out, or whether your actions were in contrast to your stated values, what knowledge and skills you had going into this situation and what your knowledge and skill gaps may be. This analytical step is often the step in which you may find that your cultural ways of being and Funds of Knowledge or values are misaligned with the family you are working with. As we work in a larger system, this is also the step during which you will need to think about what federal, state, and local systems, policies, and procedures contributed to the outcome.

The next to last step of the process is to draw a conclusion about what you can learn from this experience and what you would change about it if you could. There may be multiple conclusions to draw from any one situation. It may be helpful to choose the one that is the most pressing to address as you move into the last step of the process, planning.

The planning stage is when you focus on change and creating new practices. In this stage, you decide what’s next for you and make a concrete plan concerning how to act differently moving forward. You may need to acquire new knowledge or develop new skills. Acting on your plan may take considerable time as most meaningful learning does. As you make your action plan, I find that two strategies are especially helpful. First, plan to change one thing at a time. As you’ll learn in Chapter 6, change is a hard process. It takes time and intention to implement meaningful change.

For this reason, you can’t plan to change seventeen practices at once but instead need to focus on one thing at a time, mastering that one thing and then moving on to the next. You are more likely to internalize changes that are realistic and manageable. The other strategy is to use Aguilar’s minding the gap tool to help you isolate what category the gaps fall into and effectively plan how to bridge those gaps.