Part 6: Writing an Exhibition Guide

Learning Objectives

By the end of this section, you will be able to:

- provide context for your Heritages of Change exhibition in writing.

- put your ideas effectively into writing.

- communicate profiles and essays through writing.

- use research to support ideas in writing.

According to the University of Toronto Libraries, exhibition guides (or catalogues as they call them) “provide documentation relating to all the items displayed in a show at a museum or art gallery and they contain new scholarly insight by way of thematic essays from curators and academics,” and they “often take the form of substantial books containing an introduction, essays, works shown, crisp colour images on glossy paper, a bibliography and sometimes an index.” So an exhibition guide is a piece of writing, perhaps a book, that contains both the artifacts in the exhibit as well as context, perhaps in the form of an introduction and essays, although the format can be creative.

Michael Glover tells us that “a good [guide] must […] bring over something of the flavor, the temper, the attitude, the very feel of the show, while revealing something important to us about the nature of its subject.” That last – “reveal something important” – is a key element in thinking about what an exhibition guide should accomplish. There is relating facts about the artifacts – dates, people involved, etc. – but, more importantly, there is demonstrating a point or points about why these particular artifacts have been brought together and what they can teach us by being looked at next to each other.

In a guide, in addition to essays about overarching themes, there are also profiles of the individual artifacts. Sylvan Barnet, in A Short Guide to Writing about Art, talks about writing an effective artifact profile (also known as a catalog entry):

“Perhaps most important of all, a good entry in a catalog conveys: the inherent value of the work; the entry helps the reader and viewer to understand why the work is worth looking at and is worth reading about. In fact, a good entry should help the reader to see the work more clearly, more fully. It should make the reader want to return to the exhibition to take another look at the work (or if the exhibition is no longer available, the entry should make the reader take a second and closer look at the reproduction of the work in the catalog), and cause the reader to say mentally, ‘Ah, I hadn’t noticed that. That’s very interesting.’” (154-155)

An essential part of Barnet’s description is that an artifact profile “helps the reader to see the work more clearly, more fully.” An artifact profile is writing that communicates an idea or ideas about an artifact that the audience might not be able to interpret for themselves from simply viewing the artifact. It reveals the thoughts of the curator in selecting the particular artifact in the first place. It also provides context in order to help the audience connect the artifact to broader complexities or questions.

Activity 4.6

- Explore the exhibition guide for artist Mark Steven Greenfield’s exhibition “Black Madonna.”

- Make note of different parts of the guide and what they accomplish.

Write: Artifact Profiles

About This Type of Writing

Profile writing are articles or essays in which the writer focuses on a specific trait or behavior that reveals something essential about the subject. Much profile material comes from interviews either with the subject or with people who know about the subject. However, interviews may not always be part of a profile, for profile writers also draw on other sources of information. In creating profiles, writers usually combine the techniques of narrative, or storytelling, and reporting, or including information that answers the questions of who, what, when, where, why, and how.

You can find profile subjects everywhere. The purpose of a profile is to give readers an insight into something fundamental about the subject, whether that subject is a person, a social group, a building, a piece of art, a public space, or a cultural tradition. Writers of profiles often conduct several types of research, including interviews and field observations, as well as consult related published sources. A profile usually reveals one aspect of the subject to the audience; this focus is called an angle. To decide which angle to take, profile writers look for patterns in their research, then consider their audience when making choices about both the angle and the tone, or attitude toward the subject.

If you would like to profile a subject other than a person, you may be unsure of how to make such a focus work. This section features a profile of a cultural artifact and discusses how the elements of profile writing work within the piece.

First, here is some background to help you better understand the blog post: On December 7, 1941, Japanese fighter planes attacked the United States military base at Pearl Harbor in Hawaii, damaging or destroying more than a dozen ships and hundreds of airplanes. In direct response to this bombing and to fears that Americans of Japanese descent might spy on U.S. military installations, all Japanese immigrants and Japanese Americans living on America’s West Coast—about 120,000 men, women, and children in all—were detained in internment camps for the remainder of the war.

As you will read in the profile, people living in the camps created newspapers for fellow detainees; the subject of this profile is the newspapers themselves. Author Mark Hartsell published his profile of the newspapers, Journalism, behind Barbed Wire , on the Library of Congress blog on May 5, 2017. Look at these notes to find out how profile genre elements can work when the writer focuses on a cultural artifact such as these newspapers.

As you find when you click on the link above to visit the blog post, Hartsell uses images to show his subject to readers. Providing images can be a particularly strong choice for profiles of places or cultural artifacts.

For these journalists, the assignment was like no other: Create newspapers to tell the story of their own families being forced from their homes, to chronicle the hardships and heartaches of life behind barbed wire for Japanese-Americans held in World War II internment camps. “These are not normal times nor is this an ordinary community,” the editors of the Heart Mountain Sentinel wrote in their first issue. “There is confusion, doubt and fear mingled together with hope and courage as this community goes about the task of rebuilding many dear things that were crumbled as if by a giant hand.” Today, the Library of Congress places online a rare collection of newspapers that, like the Sentinel, were produced by Japanese-Americans interned at U.S. government camps during the war. The collection includes more than 4,600 English- and Japanese-language issues published in 13 camps and later microfilmed by the Library. “What we have the power to do is bring these more to the public,” said Malea Walker, a librarian in the Serial and Government Publications Division who contributed to the project. “I think that’s important, to bring it into the public eye to see, especially on the 75th anniversary.… Seeing the people in the Japanese internment camps as people is an important story.”

Although the blog places almost every sentence in its own “paragraph” for easier online readability, the first four sections function as a cohesive opening paragraph as presented here. Notice how the author supports his points with information synthesized from a variety of sources: quoted material from both the newspapers and one of the project’s curators, background, historical context, and other factual information.

Following the Japanese attack on Pearl Harbor in December 1941, President Franklin D. Roosevelt signed an executive order that allowed the forcible removal of nearly 120,000 U.S. citizens and residents of Japanese descent from their homes to government-run assembly and relocation camps across the West—desolate places such as Manzanar in the shadow of the Sierras, Poston in the Arizona desert, Granada on the eastern Colorado plains. There, housed in temporary barracks and surrounded by barbed wire and guard towers, the residents built wartime communities, organizing governing bodies, farms, schools, libraries. They founded newspapers, too—publications that relayed official announcements, editorialized about important issues, reported camp news, followed the exploits of Japanese-Americans in the U.S. military and recorded the daily activities of residents for whom, even in confinement, life still went on. In the camps, residents lived and died, worked and played, got married and had children. One couple got married at the Tanforan assembly center in California, then shipped out to the Topaz camp in Utah the next day. Their first home as a married couple, the Topaz Times noted, was a barracks behind barbed wire in the western Utah desert.

This section offers additional background information and information from secondary research, woven with specific details to help readers imagine the backdrop for the newspaper writing. Hartsell offers a brief overview of typical content found in these newspapers; this description indicates that he has reviewed primary documents. The section concludes with a brief anecdote to show the human face of the original camp newspaper audience.

The internees created their publications from scratch, right down to the names. The Tule Lake camp dubbed its paper the Tulean Dispatch—a compromise between The Tulean and The Dusty Dispatch, two entries in its name-the-newspaper contest. (The winners got a box of chocolates.) Most of the newspapers were simply mimeographed or sometimes handwritten, but a few were formatted and printed like big-city dailies. The Sentinel was printed by the town newspaper in nearby Cody, Wyoming, and eventually grew a circulation of 6,000.

After covering background and context, Hartsell turns to focus on his profile subject. He discusses specific details of naming and producing the newspapers; he also includes information about the writers and their decisions regarding newspaper content.

Many of the internees who edited and wrote for the camp newspapers had worked as journalists before the war. They knew this job wouldn’t be easy, requiring a delicate balance of covering news, keeping spirits up and getting along with the administration. The papers, though not explicitly censored, sometimes hesitated to cover controversial issues, such as strikes at Heart Mountain or Poston. Instead, many adopted editorial policies that would serve as “a strong constructive force in the community,” as a Poston Chronicle journalist later noted in an oral history. They mostly cooperated with the administration, stopped rumors and played up stories that would strengthen morale. Demonstrating loyalty to the U.S. was a frequent theme. The Sentinel mailed a copy of its first issue to Roosevelt in the hope, the editors wrote, that he would “find in its pages the loyalty and progress here at Heart Mountain.” A Topaz Times editorial objected to segregated Army units but nevertheless urged Japanese-American citizens to serve “to prove that the great majority of the group they represent are loyal.” “Our paper was always coming out with editorials supporting loyalty toward this country,” the Poston journalist said. “This rubbed some… the wrong way and every once in a while a delegation would come around to protest.”

People reading these newspapers in current times may be surprised that such newspapers often featured content with a focus on loyalty to the United States. While Hartsell does not dig deeply into alternative views held by internees, he does indicate that some disagreed with the emphasis on such content. Readers are often interested in learning surprising or counterintuitive information about a profile subject.

As the war neared its end in 1945, the camps prepared for closure. Residents departed, populations shrank, schools shuttered, community organizations dissolved, and newspapers signed off with “–30–,” used by journalists to mark a story’s end. That Oct. 23, the Poston Chronicle published its final issue, reflecting on the history it had both recorded and made. “For many weeks, the story of Poston has unfolded in the pages of the Chronicle,” the editors wrote. “It is the story of people who have made the best of a tragic situation; the story of their frustrations, their anxieties, their heartaches—and their pleasures, for the story has its lighter moments. Now Poston is finished; the story is ended. And we should be glad that this is so, for the story has a happy ending. The time of anxiety and of waiting is over. Life begins again.”

Hartsell closes with a chronological structure, concluding his piece with the closing of the internment camps and their newspapers. He allows the voices of the editors to have the last word.

These terms, or genre elements, are frequently used in profile writing. The following definitions apply specifically to the ways in which the terms are used in this genre.

- Anecdotes: brief stories about specific moments that offer insights into the profile subject.

- Background information: key to understanding the profile’s significance. Background information includes biographical data and other information about the history of the profile subject. It often helps establish context as well.

- Chronological order: information or a narrative presented in time order, from earliest to most recent.

- Context: the situation or circumstances that surround a profile subject. Situating profile subjects within their contexts can offer deeper insights about them.

- Factual information: accurate and verifiable data and other material gathered from research.

- Field notes: information gathered and recorded by observing the profile subject within a particular environment.

- Location: places relevant to the profile subject. For a person, location might include birthplace, place of residence, or place where events occurred.

- Narrative structure: text organized as narratives, or stories, weaving research into the story as applicable.

- Quotation: words spoken or written by the subject or from interviews about the subject.

- Reporting structure: structure that relays factual information and answers who, what, when, where, why, and how questions.

- Show and tell: descriptive and narrative techniques to help readers imagine the subject combined with reporting techniques to relay factual information.

- Spatial structure: used in profiles of buildings, artworks, and public spaces. This structure reflects a “tour” of the space or image.

- Thick description: combination of sensory perceptions to create a vivid image for readers.

- Tone: the writer’s attitude toward the subject. For example, tone can be admiring, grateful, sarcastic, disparaging, angry, respectful, gracious, neutral, and so on.

- Topical structure: structure that focuses on several specific topics within the profile.

Like introductions in most of the writing you do, the profile introduction establishes some background and context for readers to understand your main point. Think about what readers need to know in order to appreciate your angle and include that information in the introduction. Some writers prefer to compose their introductions first, whereas others wait until after they have developed a draft of the body. Whichever strategy you use, be sure that the introduction engages readers so that they want to continue reading. Refer to the sample texts in this chapter for models of introductory texts.

Remember, too, that your thesis should appear as the last sentence, or close to the end, of the introduction. For the profile, your thesis would be a sentence or two explaining your angle. For example:

- [Name of subject] showed [the admirable trait] not only in [doing something that shows the trait] but even more so by refusing to [accept or participate in something].

- [Name of subject] plays a unique part in the [history, life, culture] of [place, group] because [reason for angle].

Each body paragraph should support the angle you have taken, advancing your thesis, or main point. For each paragraph, synthesize details—examples, anecdotes, quotations, location, background information, or descriptions of events—from more than one source to support your angle. By including all of these elements, necessary explanations, and a combination of narrative and reporting, you will create the strongest possible profile piece.

Summary of Writing Task

- In thinking about each of your three selected artifacts, decide on a specific focus you want to communicate. Examples of ways to find a specific focus:

- story of the artifact

- connection to exhibition theme

- significance of artifact

- question raised

- Using your research, write a profile for each of the artifacts. Remember that a profile is more than a report, so the purpose here is only to use facts and historical information in order to develop a deeper focus.

- It is best to avoid:

- relying on simple summary (this is about contextualizing the artifact as heritage of change, not just describing it)

- making details up ( research is important)

- using jargon without further elaboration (consider your audience)

Text Attributions

This section contains material taken from “Chapter 5: Profile: Telling a Rich and Compelling Story” from Writing Guide with Handbook by Senior Contributing Authors Michelle Bachelor Robinson, Maria Jerskey, and Toby Fulwiler, with other contributing authors and is used under a CC BY 4.0 license.

Write: Exhibition Guide Essay

About This Type of Writing

Conducting research on topics about which you have limited knowledge can be intimidating. To feel more comfortable with research, you can think of it as participating in a scholarly conversation, with the understanding that all knowledge on a particular subject is connected. Even if you discover only a small amount of information on your topic, the conversations around it may have begun long before you were born and may continue beyond your lifetime. Your involvement with the topic is your way of entering a conversation with other students and scholars at this time, as you discuss and synthesize information. After you leave the conversation, or finish your research, others are likely to pick it up again.

What you find through research helps you provide solid evidence that empowers you to add productively to the conversation. Thinking of research in this way means understanding the connections among your topic, your course materials, and larger historical, social, political, and economic contexts and themes. Understanding such connectedness begins with choosing your topic and continues through all phases of your research.

The most specific way to define the scope and focus of your research paper—and, as a writer, to control the thought and creativity of it—is through the position you take on the topic: your stance, or thesis. A thesis statement is often (though not always) a single, clear, and concise sentence that reveals your stance early in the essay. Keep in mind, though, that it is not the essay question restated, a topic statement, an assertion of fact, or a step-by-step writing plan. Strong academic writing generally shows the thesis in the introductory section and then returns to it throughout, allowing readers to understand the writer’s purpose and stance. To use a travel analogy, your thesis tells readers where you are going and why the journey matters.

As you are composing your essay, the thesis serves as a touchstone to help you determine what material is pertinent. Keeping your thesis in mind as you draft is important to ensure that your reasoning and supporting evidence are focused and relevant. A strong thesis also provides a way to measure how successful you have been in achieving your purpose—in travel terms again, it lets you judge whether you have reached your destination and explained the journey’s meaning.

In a research essay, you may incorporate borrowed material through synthesis, summary, quotation, or paraphrase. Because research writing is more than cutting and pasting together other people’s ideas, good writers synthesize the material they use by looking for connections among sources to develop their own arguments. Summary—or a brief review of main points—is a necessary foundation for synthesis, but it is important to avoid constructing an essay simply on a series of summaries. Part of developing your own voice and control over your essay stems from your decision about which supports you use and why. You do not want sources to override your ideas. Remember, sources provide evidence for your thesis.

One of the most common ways to use sources is by incorporating other people’s words into your work. Students who are unsure about their writing sometimes overuse quotations, creating a patchwork essay of other people’s voices, because they may lack confidence about using their own words. However, one key point to remember is not to allow your sources to drown out your own voice. As a writer, you can avoid overreliance on others’ words by being strategic about the quotations you include and by incorporating your own explanations and analysis for the quotations that you do include. Always explain or analyze your quotations; they do not speak for themselves.

A crucial skill you will develop as you practice writing is the ability to judge when to quote directly and when to paraphrase. You have no doubt used direct quotations in your writing, repeating someone else’s words verbatim within your paper and placing them within quotation marks, “like this.” Another way to incorporate borrowed ideas into your writing is to paraphrase them, or restate them in your own words. If the ideas you want to borrow are particularly long, complicated, or filled with jargon, consider paraphrasing for brevity or clarity. Paraphrasing also allows you to maintain your own voice, keeping the writing style and language as consistent as possible—a benefit especially when you draw on multiple sources at once.

Although quoting can be more straightforward, consider these suggestions when paraphrasing:

- Focus on ideas and on understanding the paper or passage as a whole rather than skimming for specific phrases.

- Put the original text aside when you write so that it doesn’t overly influence you.

- Restructure the idea to reflect the way your brain works.

- Change the words so that the paraphrase reflects your language and tone. Think about how you would explain the idea to someone unfamiliar with your subject (your mother, your roommate, your sister).

Lead your argumentative research essay with your best punch. Make your opening so strong your reader feels compelled to continue. Make your closing so memorable your reader can’t forget it. Because readers pay special attention to openings and closings, make these sections work for you. Start with a title and lead paragraph that grab readers’ attention and alert them to what is to come. End with closings that sum up and reinforce where readers have been.

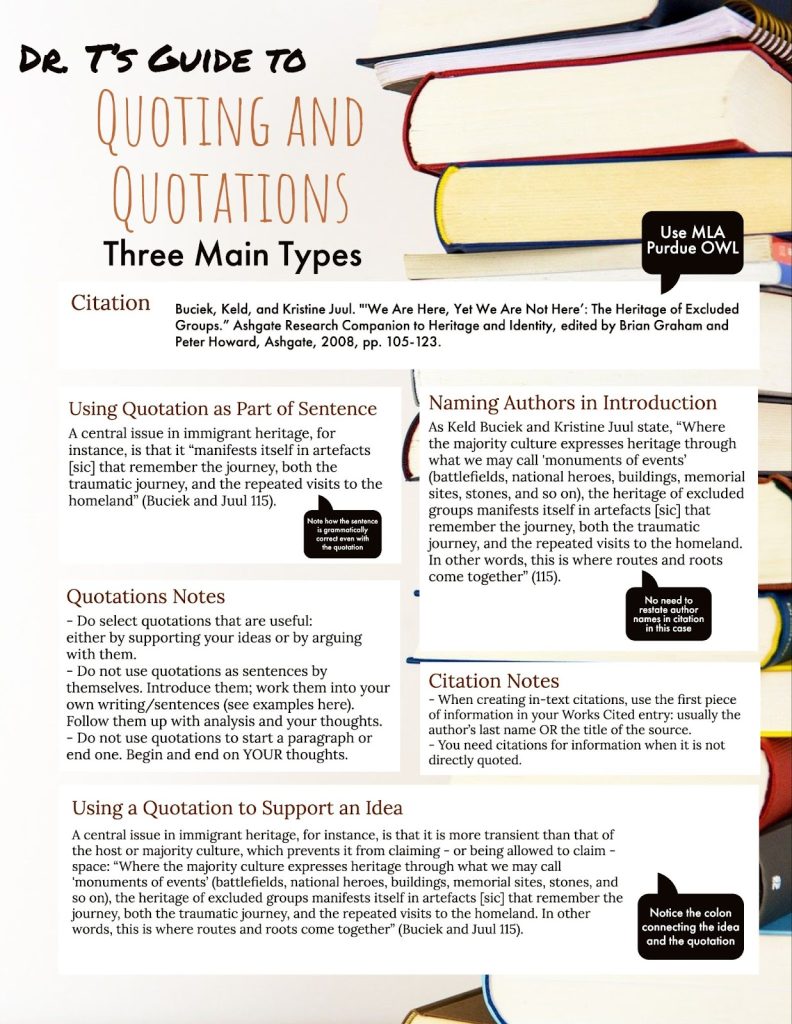

Guide to MLA Style Quoting and Quotations

Citation of Source: Buciek, Keld, and Kristine Juul. “‘We Are Here, Yet We Are Not Here’: The Heritage of Excluded Groups.” Ashgate Research Companion to Heritage and Identity, edited by Brian Graham and Peter Howard, Ashgate, 2008, pp. 105-123.

Using Quotation as Part of Sentence: A central issue in immigrant heritage, for instance, is that it “manifests itself in artefacts [sic] that remember the journey, both the traumatic journey, and the repeated visits to the homeland” (Buciek and Juul 115).

Naming Authors in Introduction: As Keld Buciek and Kristine Juul state, “Where the majority culture expresses heritage through what we may call ‘monuments of events’ (battlefields, national heroes, buildings, memorial sites, stones, and so on), the heritage of excluded groups manifests itself in artefacts [sic] that remember the journey, both the traumatic journey, and the repeated visits to the homeland. In other words, this is where routes and roots come together” (115).

Using a Quotation to Support an Idea: A central issue in immigrant heritage, for instance, is that it is more transient than that of the host or majority culture, which prevents it from claiming – or being allowed to claim – space: “Where the majority culture expresses heritage through what we may call ‘monuments of events’ (battlefields, national heroes, buildings, memorial sites, stones, and so on), the heritage of excluded groups manifests itself in artefacts [sic] that remember the journey, both the traumatic journey, and the repeated visits to the homeland. In other words, this is where routes and roots come together” (Buciek and Juul 115).

Quotations Notes:

- Do select quotations that are useful: either by supporting your ideas or by arguing with them.

- Do not use quotations as sentences by themselves. Introduce them; work them into your own writing/sentences (see examples here). Follow them up with analysis and your thoughts.

- Do not use quotations to start a paragraph or end one. Begin and end on YOUR thoughts.

Citation Notes:

- When creating in-text citations, use the first piece of information in your Works Cited entry: usually the author’s last name OR the title of the source.

- You need citations for information when it is not directly quoted.

Summary of Writing Task

- Think about the theme of your exhibition and its title.

- Using your research and including quotations where appropriate, write an essay that brings all three of your pieces of cultural heritage together to explain the theme that you have selected.

- Questions to consider:

- Why did you put these three artifacts together?

- What do you want to emphasize by bringing them together?

- What is the purpose and significance of your exhibition?

- What are you trying to communicate to your audience?

Text Attributions

This section contains material taken from “Chapter 12: Argumentative Research: Enhancing the Art of Rhetoric with Evidence” from Writing Guide with Handbook by Senior Contributing Authors Michelle Bachelor Robinson, Maria Jerskey, and Toby Fulwiler, with other contributing authors and is used under a CC BY 4.0 license.

Media Attributions

- Guide to Quotations © Kisha G. Tracy is licensed under a CC BY-NC-SA (Attribution NonCommercial ShareAlike) license