Part 3: UNSDG Intersections with Poetry & Shakespeare

Outcomes and Skills Practiced

Control of the natural environment, understood as

a god-given right in Western culture seems

to imply ecophobia, just as the use of African

slaves implies racism. Similarity, misogyny is to rape

as ecophobia is to environmental looting and

plundering. Like racism and misogyny, with

which it is often allies, ecophobia is about power.

Simon Estok, 2005

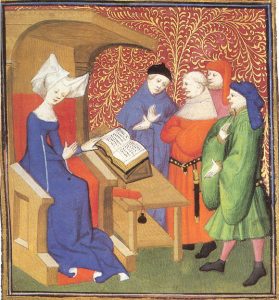

Sappho recites poetry (left), Christine de Pizan, Europe’s 1st female professional writer, & an Engraving of Shakespeare (right) CC

Key Chapters

- Chapter Eight Lyrical Poetry & Poetic Fragments of Greek Poet Sappho & Intersections with Reducing Inequality, Gender Equality, Sustainable Communities, & Decent Work

- Chapter Nine Late Medieval European Revisionism: Christine de Pizan Initiates the Renaissance & Intersections with Quality Education, Gender Equality, & Reducing Inequality

- Chapter Ten Elizabethan & Jacobean Problem Plays by Shakespeare & Intersections with No Poverty, Decent Work, Reducing Inequality, Gender Equality, & Peace & Justice from UNSDG (LINK).

Review

Part One Introduces Early Poetry, Origin Stories & the Epic with ‘Ecocritical’ Approaches

Part One features early poetry, origin stories, and the epic from Sumerian ancient cultures to more recent traditions by Indigenous communities of the Americas, the Maya, and 1200s West African literary traditions. Literary tropes are also featured to show intersections between aspects of the plot, character, and theme on UNSDG like peace and justice and life on land and agriculture, including

- Topics on sustainability pointed out by ecocritical scholars like Dr. Martin Puchner whose work on the Epic of Gilgamesh centers on the scene when the dragon is killed by Gilgamesh to show his desire to bring cedar lumber back to their kingdom. And, in Popol Vuh urban and agricultural references unveil urban development of the Maya in Mesoamerica. Sustainable ideology witnessed in the literature of several Indigenous communities offer alternative means of sustenance and livelihood.

- Ecocritical readings of the hymn, origin stories, and the epic point out the legacies of human interaction with nature to extract resources in world literature, a legacy that coincides with twenty-first century concerns on conservation and sustainability that the United Nations has outlined as goals for an overall healthier global ecology.

Part Two Continues a Familiarity with Ecocriticism in Folklore, on being human, including

- The works Aesop’s Fables, Ovid’s Metamorphoses, the fifteen-volume story collection One Thousand and One Nights, and the theatrical allegory Volpone by Ben Jonson.

- And to become acquainted with Greek, Asian, and Western literary traditions. By focusing on shorter narratives that inform on the intricacies of the web of life, literary representations and interactions between humans and the nonhuman like ‘animal fables’ are understood to rethink worldviews and a more sustainable ideology.

- The animal fable and the allegory reveal ways Western audiences negotiate their own sense of morality and ethics which in turn exposes an ideology that views the animal kingdom as less moral and inferior; hence, easily exploitable. These belief systems challenge twenty-first century readers to consider alternative narratives that are more ecological and environmentally sound.

A Preview of Part 3 and Chapters Eight, Nine, and Ten

Part Three: Literary Studies Intersects with Systemic Inequalities on Gender and Labor and Social Justice

Literary works address aspects of humanity and its superstructure on sexuality, gender, political hierarchy, and institutional religion, in lyrical poetry, allegory, and Shakespearean problem plays.

- Chapter Eight Lyrical Poetry: Offers historical context and examples on Sappho’s poetry

- Chapter Nine Europe’s Late Medieval Revisionism: Offers historical context and examples on Christine de Pizan’s revisionist allegories to recognize the contributions of women

- Chapter Ten Elizabethan Theater & Shakespeare’s Measure for Measure (1605): Offers historical context on Shakespeare’s plays on institutional inequalities and ecocriticism

Introduction of Part Three

Shakespeare’s 1602 Coat of Arms (left), two 1400s illustration of educator Pizan, & 470 BCE Sappho plays barbiton, a lyre CC

On Lyrical Poetry, Revisionism, Drama Intersections with Sustainability

The poets, writers, and dramatists in Part Three continue to inform on themes that intersect with aspects of sustainability (Toolkit, UNSDG). They will help learners to conclude this introduction to literary studies course and to prepare them to engage in problem-solving projects to address present-day sustainability challenges. Critical analysis of featured literary works allow learners to navigate different forms of injustices, like gender inequality and the abuse of power, through representations of nature and aspects of injustice beyond the individual to reveal systemic injustices, like institutional racism and sexism.

Ecocriticism throughout this book serves to enhance textual analysis and interpretative approaches to assist in identifying and rethinking the human and nonhuman binary in literary works. In a sense, ecocritical approaches demystify nature and humanity, and in doing so we learn and understand more about our treatment toward one another and other life-forms and aspects of the physical world. This cultural, emotional, and intellectual journey also assists in identifying and navigating ideology to learn more about how it unveils our roles in the interconnected web of life to face twenty-first century sustainability challenges.

Being part of the web of life, literary approaches practiced throughout this book also serve to ‘de-center’ and to ‘de-isolate’ humanity through interpretations of nature in literature. Interpretative approaches — like ecocritical theoretical analysis —also assist us to recognize our own accountability to our counterparts within the web of life.

Let’s proceed in the third and final section of this book and witness how literary works from the past and of multiple traditions continue to inform us about our own dire concerns and challenges that affect us on a daily basis. Since humanity has caused problems on climate stability and social justice, then we can learn from problem-solvers —like from L.A. Green Grounds founder Ron Finley — to rectify them.

“A Guerilla Gardener in South Central L.A.” (2013) by Ron Finley of L.A. Green Grounds TED Talk

Let’s also become acquainted with compassion, kindness, and the sense of touch, because the literature that follows includes works of poetry, allegorical narratives, and dramatic works that address human desire and passion, heartbreak and disappointment, and the human intellect and patriarchal power — featuring Greek poet Sappho, premodern author Christine de Pizan, and Shakespeare’s problem comedies, like Measure for Measure (1602).

Ἔρος δαὖτ᾿ ἐτίναξεν ἔμοι ϕρένας,

ἄνεμος κατ᾿ ὂρος δρύσιν ἐμπέσων.

Shaking my soul a gust of passion goes,

A mountain wind that on the oak-tree blows.

On Sappho’s Emergence through Lyrical Poetry

Chapter Eight of Part Three builds on our familiarity with poetry and its poetic forms in hymns, songs, and early heroic epics that Part One introduces — on rhyme, meter, and figurative language like the metaphor and symbolism. Chapter Eight also addresses lyrical poetry with a sampling of its ancient origins in the work attributed to Greek poet Sappho and recent lyrical poetry by abolitionist orator Sojourner Truth and Harlem Renaissance and Postmodern poets Jean Toomer and Etheridge Knight.

In contrast to epic poetry and heroic poetry, lyrical poems are personal and have shorter lines of verse, they are often written with music and sung with themes closer to home and about lived experiences. Lyrical poems are both informal and public,like folk songs and folklore. They address emotions and reflections to collectively inform on the gestalt of its culture and historical context.

Greek poet Sappho marks the emergence of Western ‘lyrical poetry’. Plato designated her as the Tenth Muse and many of her poems only survive in ‘fragments’.

Sappho probably wrote around 10,000 lines of poetry; today, most of that is lost. Only about 650 lines survive. A couple of complete poems and about two hundred fragments are all that remain of the nine substantial books, in diverse genres and meters, that she produced. Her poems could be consulted, complete, in the ancient libraries, including the famous one at Egyptian Alexandria. But they did not survive the millennium between the triumph of Christianity and the frantic export to the West of Greek manuscripts from Constantinople before it fell in 1453. While most of her poems have been lost, some have endured through surviving fragments (a few were found wrapping Egyptian mummies!). Of the 189 known fragments of her work, twenty contain just one readable word, thirteen have only two, and fifty-nine have ten or fewer. WordPress on Sappho

Sappho’s poetry demonstrates her role as a woman of stature in 600 B.C.E. Greek society. Her lyricism penetrates a realism rarely witnessed in antiquity poems. Through her use of imagery, her poetic lines are personal and emotionally vigorous. They were collected and read at gatherings like weddings and festivals in classical Greek society.

Activity: What do you learn about figurative language & the role of nature in poetry?

GOAL: To gain advanced practice in textual analysis in lyrical poetry

DIRECTIONS:

- Read the fragment of Sappho’s poetry below. This is a two-line fragment from one of Sappho’s poems. The fragment was translated by dramatist, poet, and thespian Ben Jonson (Gutenberg on Sappho’s Fragments & Poetry):

Ἦρος ἄγγελος ἰμερόφωνος ἀήδων.

The dear good angel of the spring,

The nightingale. - And then, observe & explain the fragment’s

- Use of imagery and metaphor

- References to nature, about a bird known to sing in the day and night

- And then, observe & explain the fragment’s

- Use of imagery and metaphor

- References to nature, about a bird known to sing in the day and night

In Jonson’s translation of a fragment of Sappho’s poetry, an ecocritical approach can unveil the role of anthropomorphism to inspire research on how ancient Greeks interacted with nature; the nonhuman.

Yet, this fragment may also offer insights into how Sappho incorporated and treated Greek mythology, because the “nightingale” is also read as figurative language, a metaphor that signifies a Greek goddess. The “dear good angel,” the ”nightingale” is a classical allusion.

In Greek mythology the nightingale refers to female demigods and goddesses, like Philomela. Philomela is physically mutilated and silenced after being raped in a Greek mythological story. The Greek mythological story about Philomela is also adapted by Roman poet Ovid in his Metamorphoses. In Ovid’s adaptation of Greek mythology, Philomela avenges her abuser. Hence, throughout Western literary traditions, the symbolism of the nightingale alludes to oppressed femininity and renewal; rebirth.

On Christine de Pizan and the Advent of the French Renaissance

Chapter Nine of Part Three features the work of Christine de Pizan. Emulating Ovid, Dante, and Boccaccio, the work of Christine de Pizan challenges medieval French social norms and anticipates the European Renaissance and humanist thought to reform representations of women in Western literature.

Christine de Pizan wrote from the early 1400s through the 1430s. Influences of The Divine Comedy by Dante Alighieri’s (Dante 1321) are demonstrated throughout her seminal work The Book of the City of Ladies. Like Dantes’ protagonist, Pizan’s narrator visits key classical and historical figures in a dream vision to address the role and significance of women.

For example, when Sappho is featured in Chapter XXX of her book The Book of the City of Ladies, Pizan’s narrator learns about Sappho’s poetic genius that compares to Roman poets like Horace and whose influences are closely associated with classical philosophers Plato and Aristotle:

“She [Sappho] invented different genres of lyric poetry, short narratives, tearful laments…Horace recounts, concerning her poems, that when Plato, the great philosopher who was Aristotle’s teacher, died, a book of Sappho’s poems was found under his pillow” (I. 30. 1).

Although she was born in Venice, Italy, Christine de Pizan moved to France at three years of age when her father served the ruling classes in Paris. While growing up in the High Middle Ages, Christine de Pizan was educated by tutors and had access to private library collections. At twenty-five years old, she became a public figure through her publications after the death of her husband left her with three children and her mother-in-law to care for alone. Themes in her work show the political life of France and a defense of women, which scholars now designate Pizan’s work as proto-feminism.

For example, Christine de Pizan’s time in France coincided with the Hundred Years’ War between England and France when influential historical figures were widely celebrated, like Joan of Arc. Joan of Arc’s role in the Hundred Years’ War by the early 1400s inspired Pizan to write the first published poem on Joan of Arc. Pizan’s epic poem The Song of Joan of Arc (1429) represents women to be the ideal moral Christian figure, a theme that exists throughout her work as a literary trope.

XXXV

A girl of only sixteen years

(Does this not outdo Nature’s skill?)

Who lightly heavy weapons bears,

Of strong and hard food takes her fill,

And thus is like it. And God’s foes

Before her swiftly fleeing run,

She did this in the public eye.

There tarried not a single one.

The poem celebrates the heroism of Joan of Arc and her military feats that elevated women’s role and voices comparable to male roles in late medieval Europe. Christine de Pizan directly references the Bible as scripture and classical mythology to elevate and demonstrate the humility and dignity of the historical Joan of Arc, a theme prevalent throughout her work.

“This image of Rhetoric as a strong, armed woman was a familiar motif in medieval illustrations” (Holland Hewett 2021).

The literary climate in Paris, France during Christine de Pizan’s upbringing was an era when French popular works expressed escalating gender biases toward women. To renew gender identities, Pizan’s work dismantles such popular notions of rigid gender roles to empower women. To achieve these goals, she revised classical mythology in her efforts to confront and reform uninformed notions of women. Pizan also redefines the dream vision in her seminal revisionist work The Book of the City of Ladies (1405), which is recognized as a masterpiece of world literature. The Book of the City of Ladies is an early work written in the French vernacular with feminist values and a style that demonstrate Pizan’s “experimental and innovative nature” (Richards 1998).

Becoming one of the first feminist writers of her time, she believed that all women should have the right to an education. Pizan wrote forty-one known pieces during her time, using the French vernacular. Pizan’s platform encouraged women to challenge the unethical ideas that women were not entitled to rights and were the property of men. (Pressbooks on Rhetoric of Pizan)

Christine de Pizan is France’s first professional woman writer and one of France’s first vernacular authors who also supervised her own copyediting and illustrations of her works.

“Christine de Pizan was, therefore, both a writer and a scholar, welding together an enormous creative drive and a deep love of learning… [and] might best be considered a polyscribator, since she wrote on so many diverse subjects” (Richard 1998).

By the 1400s, the European literary imagination became less preoccupied with the Romance, due to disillusionment in the Roman Catholic Church and the rise of the Protestant Reformation. By the end of the High Middle Ages, at the advent of 1450s and the European Renaissance, Europe’s early modern era will reshape European poetry and drama. The medieval romance and emerging feminism of the late middle ages also gave way to the rise to new investments in innovation and human potential, which will later be regarded as Humanism, a European cultural and philosophical movement in the 1600s that stemmed from the Renaissance to address morality, governance, and self-fashioning.

1800s painting titled Procession of Characters from Shakespeare’s Play by unknown artist CC

On William Shakespeare and Jacobean England

Chapter Ten of Part Three features several problem plays by William Shakespeare. This book completes with Shakespearean early modern drama to recognize their merits while they inform on challenges we witness today, especially throughout institutional inequalities, like gender equality and systemic racism; UNSDG challenges (Toolkit in Pressbooks).

A prevalent literary trope in early modern English drama is plays set in foreign lands. Christopher Marlowe’s Doctor Faustus (1588) is set in Germany and Ben Jonson’s Volpone; Or the Fox (1606) in Venice, Italy. Most of Shakespeare’s plays are also set in foreign lands, which include his problem plays Measure for Measure (1598), The Merchant of Venice (1598), and The Winter’s Tale (1609). His tragedies are also set beyond England: Romeo and Juliet (1594) is set in Verona, Italy; Hamlet (1597) in Helsingør, Denmark; Macbeth (1606) is set mainly in Scotland; and The Tempest (1610) is set at an unnamed remote island, which alludes to the Caribbean.

Scholars and laypeople alike know of William Shakespeare’s Romeo and Juliet and Hamlet, and even King Lear and Macbeth. But most are probably not familiar with the source materials available to Elizabethan and Jacobean dramatists like William Shakespeare. When writers reimagine source materials in their own works, this is an instance of an adaptation.

Many writers utilize source materials to modify certain aspects of a source and to add new ideas for the purpose of creating a different, contemporaneous version. This process is described in film theory as innovation: “…the adaptation of one from the other produces a new and wholly autonomous art form” (Bluestone 1957). This implies that any work that has aspects of a previous version can be recognized for its ingenuity, regardless of being a remake. Many of Shakespeare’s dramatic adaptations are recognized for their ingenuity regardless of the source materials, like Romeo and Juliet, Hamlet, King Lear, The Merchant of Venice, and Macbeth.

On Shakespeare’s Jacobean Poetry and Dramatic Theater & Ecocriticism

In addition to source materials, Elizabethan dramatists and poets were also inspired by the European Renaissance. They researched classical works and created works with classical allusions, like Ovid’s Metamorphoses. Like the literature from other literary traditions and from various geographic regions and worldviews featured in Part One and Part Two of this book, themes of the literary works in Part Three are investigated through textual analysis and criticism informed by Cultural Studies, Ethnic Studies, and Gender Studies, as well as feminism, marxism, postcolonialism, but especially ecocriticism. The works of William Shakespeare are no exception.

“Ecocriticism has become a valid perspective in the literary field and interdisciplinary education practices. It has also made its way into Shakespeare scholarship” (Abou-Agag 2016).

One theme prevalent throughout Ovid’s Metamorphoses incorporated in early modern drama is the ever-changing dynamics of nature, which is represented in many instances by gender fluidity. Gender fluidity is one theme that is represented throughout Shakespeare’s work, including his sonnets. Through instances of wordplay — like malapropisms, puns, or wit — a Shakespearean poem centers on its gender shifting object of desire.

For example, Sonnet XX shows gender as changing and natural, through a witty emphasis of the word “nothing,” which serves as a pun.

Till Nature, as she wrought thee, fell a-doting,

And by addition me of thee defeated,

By adding one thing to my purpose nothing.

Through imagery and word choice, Shakespeare’s poem addresses a beloved who is both male and female. Scholars read the beloved as “a woman trapped within a man’s body.” And to emphasize this point, Shakespeare adds the word “nothing” — a term that implies the beloved’s male reproductive organ.

Attention to the role of nature in this sonnet also shows its agency with creation. A theme on gender fluidity emerges where nature, a part of the web of life, is gendered female. This poem also inverts the Narcissus Greek myth. The Greek myth has Narcissus falling in love with his own image. This sonnet has Nature falling in love with her own image. This treatment of nature in Sonnet XX is also represented throughout Shakespeare’s work, a theme that unveils the dynamic qualities of nature, which the Great Chain of Being keeps static. Other instances of gender fluidity are demonstrated by ecocritics in Shakespeare’s Twelfth Night (1601).

Ecocritics like Steve Mentz, with whom we began this journey in the introduction of Part One, point to our present-day historical context and on its media-driven narratives that resemble the evening news hour to highlight aspects of our hostile world, hostilities, Mentz claims, that are inherently toward the web of life itself, which — ironically —are human-made hostilities.

“Crisis is creating new patterns and more drastic narratives, populated with drowning polar bears, warming oceans, and killing storms. These stories do not fit the post-Enlightenment patterns of progress and stability” (Mentz 2013).

Mentz continues his argument by reviewing the work of Shakespeare to address characters who also face a ‘hostile world.’. Mentz immediately points to King Lear, a well-known and acclaimed Shakespearean figure who ironically suffers hostilities of his own doing. In addition the plot devices of conflict and dramatic irony, themes on hostile situations become another literary trope throughout Shakespeare’s dramatic works:

- Romeo and Juliet are torn by two rivaling families who are more invested in maintaining affluence and power than securing the safety of their children, which exposes the inhumane hierarchical structure of class in Europe.

- Othello is a tragedy understood through cultural practices of othering its members or outsiders, due to prejudice at the surface, but motives run more deeply among political alliances. Iago’s jealousy shows the military culture of the time that is the embodiment of Othello. Being of non-European, non-Christian, and North African origins, Othello represents modern versions of legitimate cultures and people who become dispossessed because of —and not despite of— their talents.

- A Winter’s Tale centers on a life-threatening ruler, whose delusion destabilizes members of the royal family and loyalists.

A historicist interpretation of Shakespeare’s lived experiences is considered in ecocriticism in order to illustrate associations between the literary trope of hostile situations throughout his works with intersections on ecology:

For example, it is argued that Shakespeare lived at a time of both civil and political restructuring, due to the decisions of Queen Elizabeth’s father Henry VIII in the 1550s that led to tensions toward civil unrest between newly misaligned religious and political factions.

Demand for timber to build Shakespeare’s New Place in Stratford or playhouses in London sent prices soaring and depleted local woodlands. New fuel-intensive industries such as iron-making for King John’s or Othello’s cannons, or glass-firing for windows like the bays and bows in Twelfth Night (4.2.37-38) and Troilus and Cressida (1.2.106), turned deforestation into England’s first major environmental crisis. Shakespeare’s Climate Crisis

Media Attributions

- Sappho © Yale Center for British Art is licensed under a Public Domain license

- Christine de Pisan © Wikipedia is licensed under a CC0 (Creative Commons Zero) license

- Shakespreare © Folger Shakespeare Library is licensed under a CC BY (Attribution) license

- Procession of Characters © Wikipedia is licensed under a CC0 (Creative Commons Zero) license

A literary trope is a recognizable plot element, theme, or visual cue that has figurative meaning. It can appear within the body of an author’s work, within a tradition, and across cultures as witnessed in world literature and world mythology. A common literary trope is the hero’s journey, which is a plot structure found in stories all around the world. Many literary tropes may not be universally understood, but occur commonly within a specific tradition – like in gothic and fantasy literature, and also in popular comics. Another recognizable literary trope that is observed in Western letters is the symbolism of skulls, like the skull Shakespeare’s Hamlet holds when he delivers his “Alas poor Yorick” soliloquy. In this scene, the skull represents a contemplation of one’s morality in the face of contradicting desires. Yet, as a religious Catholic trope a skull is associated with Jesus of Nazareth, for example. This association may signify more directly with death. Yet, in most religious contexts, skulls are associated with the life-cycle. For example, a skull in Mexican cultural traditions represents this meaning, through rituals associated with the Day of the Dead. They involve visiting and speaking with the deceased at nearby cemeteries, among other rituals; here, the skull signifies the life-cycle. The skull may also share associations with the serpent, like in Chinese and Mesoamerican traditions. Yet, the ‘serpent’ in most Western texts –the New Testament, Ovid’s Medusa, and even popular texts like Harry Potter – is usually associated with demons and the unholy, a finite view of the life-cycle. Another literary trope common in European literary texts is the color ‘white’. In many instances this color means death when associated with snow. Witnessed in James Joyce’s 1914 story “The Dead” from Dubliners, snow is a metaphor that signifies the death of a beloved and of a marriage (Wiki on Joyce's "The Dead" from Dubliners).

Intersectionality is the “study of overlapping, intersecting social identities and related systems of oppression, domination, or discrimination” (Syracuse University). Intersectionality was first posed on Langston Hughes poetry to highlight intersections between racism and the legacy of slavery with environmental exploitation and that of Black laborers, where learners can conduct further research on such overlapping topics. For example, learners can research Black oppression in the 1840s through the work of America’s first ‘Father of Black Nationalism’ Martin R. Delany, in order to learn about the effects of slavery, while researching Joni Adamson’s work on environmental devastation. Intersectionality is a concept coined by American law expert Dr. Kimberlé Crenshaw in a 1989 paper to address the oppression of African women to address that gender and racism are not “mutually exclusive categories of experience and analysis.” In legal matters, injustices on both gender and race are considered separately in the U.S. The tendency to simplify a composite of injustices that are all related is described as interpreting the law on a ‘single axis framework’ (on its history). To remedy this oversimplification, Crenshaw coins the idea of ‘intersectionality’ as an approach that recognizes the complex composite nature of an injustice that reflects several injustices at once. Her goal is to make Black women more visible and for the law to acknowledge their plight as women of color (Sociology & Intersectionality). Intersectionality is a lens through which you can see where power comes and collides, and where it interlocks. “It’s not simply that there’s a race problem here, a gender problem here, and a class or LBGTQ problem there. Many times that framework erases what happens to people who are subject to all of these things'' (Columbia Law School).

A concept that encompasses the dynamic and intricate network of how humanity affects communities, the environment, and climate. Current efforts to address a wide array of cultural and sociological practices that are all interrelated and connected to seriously address the causes and effects of ‘climate instability’ and other injustices that plague some societies while threatening the rest. The United Nations offers 17 goals of development to highlight many facets of society – from the production of goods and treatment of women and the impoverished and social justice and renewable energies (UNSDG ). Yet, current scholarship by ecocritics in literature emphasizes the fundamental need to address today’s crisis – a sustainable ideology, to demystify human and nonhuman binary thinking. Where we as a global people realize that we are interconnected to local and global ecologies. This worldview can also demystify current human tendencies of placing humanity above the nonhuman. An example of this argument is witnessed in Frank Boom’s ecocritical analysis of Ovid’s Metamorphosis, Book 10 and 11, on the mythological tales of “Orpheus and Cyparissus” (OER Article on Today's Climate Crisis & Ovid's "Metamorphoses").

“A more or less systematic ordering of ideas with associated doctrines, attitudes, beliefs, and symbols that together form a more or less coherent philosophy or Weltanschauung for a person, group, or sociopolitical movement” (APA Dictionary qtd. BU Equity Guide). In schools of thought such as political science and psychology, ideology is addressed as a system of beliefs that underpins and sustains the form of a society. A school may be supported by an ideology of curricular vigor that rewards certain achievers. The economy of a country may be supported by a capitalist ideology. But, ideology is also understood through other worldviews and cultural norms, like those practiced by the Indigenous communities of the Americas.

The concept of nature is a social construct with qualifiers that make nature idyllic, or ‘balanced.’ Yet, in non-Western literary traditions, references to nature reflect real lived experiences, immersed in nature. For example, in Indigenous oral traditions, nature is dynamic. Adamson explains, “They tell of wars, crisis, and famine…they learned to live with ambiguities, to see the patterns, and to mimic natural processes in the cultivation of their gardens” (Adamson 56). Ecocritics and environmental humanists, among other scholars, witness humans as also a social construct in opposition to nature, or the nonhuman, which is witnessed throughout literature. Instances of the feminization of nature are understood as gendered ethnocentric views of nature by those who define humanity as superior to nature, and the masculine gender as superior to the female gender. These social constructions suggest anxieties about what it means to be human and overlap with discourses on power and colonialism when the colonized are effeminate, along with the conquered landscape. The gendering of a people and nature acts as a mechanism that initiated modernity, inequalities ecofeminist Soper addresses, “given the widely perceived parallels between the oppression of women and the destruction of nature” (Soper 1995). Feminist philosopher Kate Soper also argues on how nature is an ‘otherness’ in What is Nature: Culture, Politics, and the Non-Human (1995) to focus on Western attitudes from two schools of thought, on ecology and cultural criticism - that of our current climate crisis and efforts to address this crisis while understanding “the politics of the idea of nature,” on the semiotics of ‘nature’. Intersections between perception of nature and theories of sexuality offer insights into ‘the politics of the idea of nature.’

United Nations Sustainable Development Guide (UNSDG)

In 2015 countries around the world came together to address challenges and needs “For a Sustainable Future” with peace, prosperity, health, equality, and justice for our community members and nature.

GOAL 3: Good Health and Well-being

GOAL 6: Clean Water and Sanitation

GOAL 7: Affordable and Clean Energy

GOAL 8: Decent Work and Economic Growth

GOAL 9: Industry, Innovation and Infrastructure

GOAL 11: Sustainable Cities and Communities

GOAL 12: Responsible Consumption and Production

GOAL 16: Peace and Justice Strong Institutions

GOAL 17: Partnerships to achieve the Goal

Claiming to be greatly influenced by Greek and Roman traditions, the Western literary tradition also reflects Arabic scholarship that includes the East – along with its technologies and cultural exchanges – and Indo-European linguistic traditions throughout Europe and its colonized territories – like the Americas – known as the romantic languages. This excludes Indigenous peoples and Slavic; yet, semitic language, religious thought, and near East influences are part of the Western tradition.

According to ecocritic Lawrence Buell’s definition of ecocriticism, which involves the philosophical view that “human being and human consciousness are thought to be grounded in intimate interdependence with the nonhuman living world,” this “interdependence” is the web of life (Buell 2011). According to Danel Wildcat and Dine Deloria Jr. – whose son is currently History faculty at Harvard Dr. Philip Deloria (wiki on Philip Deloria), the worldview, the metaphysics of Indigenous peoples in North America experience reality as ‘related,’ the world is unified, and all aspects have significance and share a commonality among the tangible, spiritual, intelligent, and intangible. “The teachings of the tribe are almost always more complete, but they are oriented toward a far greater understanding of reality than is scientific knowledge”(OER Pressbooks on Indigenous Education, go to Ch. 9). As a more thorough and intuitive philosophy, they expose the limitations and exclusionary culture of Western culture and its reliance on Cartesian dualistic philosophy: “We live in an industrial, technological world in which a knowledge of science is often the key to employment, and in many cases is essential to understanding how the larger society views and uses the natural world, including, unfortunately, people and animals.”

alternative narratives are understood as stories read through a proposed critical lens, like ecocriticism. Visit Key Terms for more information.

This phrase in academic circles, especially in the Humanities is a broad way of engaging with a text – in anthropology, communication, history, literature, philosophy, political science – for the purpose of concretely understanding both its content and role in a particular discipline and school of thought. For a more detailed understanding of textual analysis go to OER Intro. to Humanities Book.

interpretative approaches aka interpretative lenses guide is explained by a diagram to help learners to build on ‘initial understandings’. Visit Key Terms for more information.

Sappho is from Crete of the Isles of Lesbos in the Mediterranean and lived during the archaic era of Greece 800 - 450 BCE. She lived at a time when early Greek philosophy emerged from the pre-Socratics. Sappho is a Greek poet from 600-450 BCE, just prior to classical Greece. She is known as a public poet and an educator, and her poetry survived due to its popularity and role in public events – her poetry was recited at weddings. Sappho follows Homer 200 years; he wrote down the ancient Greek epics The Iliad and The Odyssey by 800 BCE. These epics were part of ancient Greek oral tradition from 1200 BCE. Sappho’s early poetry emerged prior to the classical era of Greece, 500-400 BCE when the idea of democracy became known in Athens.

rhyme (also go poetic genres), in an introduction to a Literary Studies course, is a poetic device featured throughout early hymns and poetry to engages student and support understandings its merits and purpose in folklore, songs, hymns, the epic, and lyrical poetry – the ode, sonnet, elegy, ballad, among others.

Meter is a collective term for the rhythmic pattern of a poem. There are several metric systems. A text written in meters is called a verse.

figurative language means uses of language that are not meant to be interpreted and understood in literal terms. For example, the American phrase, ‘the apple of my eye’ has the “apple” as a symbol, which is a form of figurative language. Visit Key Terms for more details.

In literary texts, in common speech, and in performative pieces like poetry and theater, metaphor is a form of a figure of speech where two or more elements of a different nature are compared with each other, but without “like” or “as.” If the comparison includes “like” or “as,” this form of a figure of speech is known to be a simile.

A symbol is an object, expression or event that represents an idea beyond itself. The weather and light/darkness will often have a symbolic meaning. Survey of Native American Literature: Symbols in Literature

Plato is an early Greek philosopher, and his book is a dialogue on justice that includes the ‘allegory of the cave,’ an allegory to demonstrate how educators should support learning and not dictate information. Students learn by engaging their own faculties as a process instilled in them. Those who desire to learn more about how to differentiate information from knowledge can look into numerous philosophies on how we need to understand our emotional impulses and seek out facts, which are less subjective and may be tested and verified. This confusion is called expressivism. (Story: Plato's Allegory of the Cave)

A student of Plato, Aristotle shared his criticism of early poetry: Greek drama, the epic, and lyrical poetry in what has become to be known as Poetics (335 B.C.E.). Aristotle’s critique of poetry may stem from his views of sophists in his day who spoke to the public in ways that misrepresent and hinder critical thinking – reason was understood as one way to reach the realities hidden from most people, as demonstrated in Plato’s Allegory of the Cave. According to Aristotle, Poetry goes beyond imitation in dramatic works like the tragedy, whose origins stem from religious groups, like the Dionysian cult rituals. Poetry in performance addresses philosophy, rather than simply representing perceived lived experiences.

A framing device in late medieval European allegorical narrative poems, like the French allegorical dream-vision on the ‘lover’s complaint in Old French titled The Romance of the Rose (1230-1275) by Guillaume de Lorris and Jean de Meun is allegorical dream-vision. Allegorical dream-visions begin with its protagonist falling asleep. The narrative that follows is a dream-vision with symbolic and allegorical characters, like the Rose, Friend, Genius, Nature, and Reason. Christine de Pizan wrote dream-visions to reform this tradition.

Humanism is understood as a concept that denotes many aspects of the European renaissance, a cultural revival movement. Specifically, though, humanism signifies the human as a master of his universe; where we can seek within ourselves for answers while we also appreciate our shortcomings and inner contradictions. Humanists placed humanity’s life at the center but still advocated Christian values. Humanism also reflects moral philosophy, history, poetry, and language aesthetics. Unlike Puritanism, humanists were more concerned with intellectual development and less about the immorality of the soul. They valued early antiquity and Christianity while critiquing medieval culture and society. Education was key, as was the matter of virtue (masculine power as moral). Becoming learned served your virtue. Michel Montaigne considered himself a humanist whose philosophical concerns resided on morality.

Was coined by Hamilton and in 1967, Black Power. In the preface of Black Power Ture and Hamilton outline the purpose of their project for Black independence liberated from oppressed by a system that repeatedly has proven to subjugate and co-opt Black achievements only to reward individual efforts to remain docile and maintain the status quo. Black Power offers ways to liberate the people of Africa and Pan-Africanism that include Black consciousness. Their method is well-thought out, “In order to find effective solutions, one must formulate the problem correctly. One must start from premises rooted in truth and reality rather than myth” (Preface xvi). OER on Institutional Racism

(“eco” in Greek is household, ecology is the learning of the life of populations)

What is ecocriticism? At first sight, it is simply a literary theory to learn about nature in literature; when critics approach literature to learn about nature, they are offering ‘ecocritical’ interpretations. Ecocriticism aims to not reduce nature into a concept or social construct, which the Western tradition shows in the majority of its literary traditions. Literary studies offers a platform to learn about representations of nature in texts, while analyzing themes on social injustices, which may share similar treatments, since “ecocriticism is a theory that seeks to relate literary works to the natural environment” (Estok 2005). Another explanation is “the study of the relationship between literature and the physical environment” and “takes an earth-centered approach to literary studies” (Glotfelty and Fromm 1996). Another explains that, “Ecocriticism examines the representation of and relationships between the biophysical environment and texts, predominantly through ecological theory” (Chisty 2021). Since the 2000s, ecocriticism has relied on scientific and philosophical approaches to understand humanity’s place in the world. The UNSDG offer a wide-ranging view of aspects of human’s roles to address current injustices and the climate crisis. Partly, it is “committed to effecting change by analyzing the function – thematic, artistic, social, historical, ideological, theoretical, or otherwise – of the natural environment.” Ecocritical readings on environmental injustices can intersect with social injustices, like Langston Hughes’ poem expresses. *Go to the section on Langston Hughes’ poem A Dream Deferred in the introduction of this book. This class supports intersections between social injustices and environmental ones. The work of Joni Adamson, American Indian Literature, Environmental Justice, and Ecocriticism: The Middle Place (2001) features the literatures of Indigenous communities and literary analyses with ecocritical understandings to address and expose Western abuse of nature and the causes of our current environmental crises, while demonstrating the literary and storytelling traditions of Indigenous communities as ‘an alternative’ theory. For more information, visit OER on Ecocriticism. This literary theory stems from the first wave of environmentalism in the U.S. by ecofeminism. The term ecocriticism emerged in the article Literature and Ecology (1978) by William Rueckert and an earlier work in 1972 by William Meeker The Comedy of Survival: Studies in Literary Ecology. “First wave" environmental criticism concerns itself with conventional nature writing and conservation-oriented environmentalism, which traces its origins to the work of Ralph Waldo Emerson, Henry David Thoreau, and John Muir. "Second wave" environmental criticism redefines the environment in terms of the seventeen Principles of Environmental Justice and increasingly concerns itself with "issues of environmental welfare and equity" and "critique of the demographic homogeneity of traditional environmental movements and academic environmental studies” (17 Principles of Environmental Justice). A modern third wave of ecocriticism recognizes ethnic and national particularities and yet transcends ethnic and national boundaries; this third wave explores all facets of human experience from an environmental viewpoint” (Adamson 2009). Originally, ecocritics looked at the relationship between literature and nature – between culture and the global environment. Literature shows human tendencies to anthropomorphize nature. Ecocritics see culture as hierarchical and in contrast to nature, especially in Western texts. To analyze this relationship, nature needs to be distinct from human constructs: the wilderness, scenic sublime, countryside, and domestic picturesque. Man-made factors are social orders and political constructs like culture and poverty. Yet, the ‘setting’ of narratives may also be fantastic – as in folklore, the gothic, and science fiction, and hence is also fertile soil for ecocritical readings. Ecocriticism takes as its subject the interconnections between nature and culture, specifically the cultural artifacts of language and literature. As a critical stance, “it has one foot in literature and the other on land; as a theoretical discourse, it negotiates between the human and the nonhuman" (Glotfelty and Fromm qtd. in Sandner 2000). The roots of the environmental movement can be traced back to the abolition movement, which revealed the connections between colonization, conquest, slavery, resource exploitation, and capital, and many of the most successful strategies of early environmentalism were borrowed from the abolition, civil rights, and women's movements and American Indian Land Claims lawsuits. For this reason, “any history of environmentalism that did not include W. E. B. Du Bois, Rosa Parks, Martin Luther King, Jr., or Cesar Chavez, among others, would need to be revised” (Adamson 2009).