A Preview of Part One

What Does Part One Provide on Early Folklore of the Hymn and Folk Song, Mythology, and the Epic?

Folklore from early ancient Sumerian hymns by Enheduanna are featured in Chapter One to showcase early versions of poetry and its aesthetics. Origin and creation mythological stories by the Haudenosaunee and Anishinaabe Indigenous communities of the Northern Region of America are featured in Chapter Two to showcase early versions of the narrative and representations of nature – as web of life. The epic by the Mesopotamians, the Mali people of West Africa, and the Maya of Mesoamerica is featured in Chapter Three to showcase the hero’s journey as a literary trope to negotiate human-nature binary and paradoxes between human civilization and the web of life.

Which Stories Matter to You and Why?

Stories emerge from the communities they serve. They are candid. They are sacred rituals. These stories tap into variations of oral traditions and folklore of the past.

Today, we can experience living storytelling cultures by the literary works of Indigenous communities. And, their storytelling instructs us. This point is profoundly clear in Why Indigenous Literature Matters (2018) by Daniel Heath Justice of the First Nation. The book closes with Justice retelling a childhood experience. He shares an eye-opening experience about his favorite childhood book for the purpose of explaining why Indigenous stories matter, including to him. His experience resonates.

“Without reliable stories of our past and our relations, I turned, as always, to books to make sense of who we were…And in the absence of viable family stories and any lived experience of grounded Cherokee culture, The Education of Little Tree filled that space with simplistic, romantic noble savages disconnected from community, ceremony, and kinship” (Justice 207).

If you are like me, then you and your present generation have very little to no ties to an Indigenous past. Justice found himself in a similar situation, which converged in him identifying with popular children’s literature. However, Justice has had a lifelong commitment to Indigenous communities and one that has been educational and reciprocal through relationships.

“To read and listen to these words – in prose and poetry, ceremony and song – and to share, study, consider, and teach them, is sacred trust, one in which imaginations are set free of settler shackles and new possibilities of humanity, kinship, heritage, and relationship are realized” (Justice 205).

Justice’s commitment to Indigenous literature inspires us to also see how stories matter in our own communities. His work shows the strength of many peoples whose own knowledge, multigenerational cultures, and love for one another cannot be easily erased, because they are sustained by stories.

How Do Popular and Folk Songs Reflect Lyrical Poetry?

Every day we experience the legacies of oral tradition and ancient literature, through the songs we compile and lyrics we memorize. Most of us virtually store songs in personal computers and MP3 players. As we proceed, make efforts to explain the theme of one of your songs in your own playlists. Talk about them with colleagues and peers and revisit the very same songs. The more time is spent with a piece of literature – even in its popular version – the more we learn about its merits, expressed realities, and about ourselves. Do you or your peers notice a common theme throughout your favorite songs?

Song lyrics reflect literary devices also seen in poetry: rhythm, repetition, irony, and metaphor. Like lyrical poetry, popular songs are accompanied with musical instruments and come in different styles, including pop songs, hip hop, punk, and the blues. Folk songs also have different forms – like protest songs of the 1960s and corridos from the Northern Mexican region. Differences in folk song traditions reflect a respective culture and geographic region. The similarities between songs and poetry cannot be understated; Both songs and poetry:

- Share poetic devices: rhyme, meter, repetition, alliteration, imagery, metaphor, theme.

- Involve ‘affect’, that is, emotions. We connect with songs on an emotional level. They inspire our emotions and in turn enhance our own sense of self.

- Contribute to ‘identity’ formation, like ancient hymns.

Let’s proceed with an activity on a 3000-year-old ancient song to learn about songs, and its poetics.

A Listening Activity: Practice identifying rhythm and repetition in songs

GOAL: To practice listening: To identify repetition of sound (more specifically, rhythm) in ancient instrumental music

DIRECTION: Let’s simply listen to perhaps the oldest known song, a cult hymn from the region of today’s Syria. This ancient hymn is an example of a fertility song from 3400 years ago.

Morning Concert: An Hurrian Cult Song from Ancient Ugarit

(An ancient fertility hymn, the oldest known song by the Ugarit, Syria region 1400 BCE)

-

Simply listen to its sounds and rhymes since its language is ancient.

-

Notice the variations, a) of its lyrics and b) of its accompaniment music, a lyre

-

Do you notice its rhythm?

-

Repetition? Tempo?

-

Is its structure consistent?

-

-

Then, listen to the 1978 interview of Dr. Anne Draffkorn Kilmer from the University of California, Berkeley by Radio Producer Charles Amirkhanian, on the role of this ancient fertility hymn:

-

What do you find most intriguing?

-

On its theme of childbirth (26:00-27:00)? On the ancient Hurrian people, from the Bronze Age? Its connection with the ‘flood story’ and overpopulation?

-

*Note, scholars do not agree on its being an “incantation hymn”

-

What Are Some Examples of Regional Folk Songs and How Do They Address Sustainability?

Outcome and Skill Practiced

Close reading of folk songs to identify literary and poetic elements in corridos and protest songs.

A well-known style of regional folk music is the corrido, from the Mexico-U.S border region. Corridos are narrative ballads, songs specific to its historical and political history: “…the form that developed in Mexico in the late 1800s is deeply rooted in that country’s specific cultural history, and especially the inequitable relationship with its conquering neighbor to the North” (Garza 2017). Corridos narrate injustices experienced by its Spanish-speaking communities throughout the region. A subgenre of the corrido is the narcocorrido (Narcocorridos Podcast). The popularization of the narcocorrido is showcased in the second season of AMC’s Breaking Bad (2009). Bilingual Educator of Northern Arizona University, playwright, and music producer Robert Neustadt cannot overstate the cultural role and value of corridos. “Music constitutes a powerful vehicle with which to raise awareness about the contemporary crisis on the border.” Neustadt’s scholarship on folk songs and corridos emphasizes the role of ‘narrative scholarship’ in Folklore Studies and Border Studies. Corridos share a folkloric style reflective of the culture of its geographic region: a corrido has stanzas of four to six lines and up to eight stressed and unstressed syllables per line, like the trochee or its opposite unstressed and stressed, in iambic and poetic devices and figurative language. For example, the popular song “The Land That I Love” by Scott Ainslie from the compilation Border Songs (2012) has corrido folkloric themes and form. Robert Neustadt points to how this song refers to the ‘push factors’ that motivate Mexicans and Central Americans to attempt to cross the border. Take note of the a) tone of the song, b) role of images, and c) source of conflict.

I go to the market, in the town I was born, It’s full of cheap clothes from China, and American corn. But we have a small farm that we water with tears. How can we compete? The gringo farms are so big. Now we cannot stay here: OER: Borderland Culture Corrido Song. In Ainslie’s song the nonhuman serves as a metaphor for commerce and manufactured products: “cheap clothes from China” and “American corn.” Collectively, these metaphors inform both industrialized farming and global over-production and consumption culture at the border region, a region historically well known for its vast wilderness and wildlife and newly established ‘maquiladoras’, since the late 1900s, which Neustadt identifies as the unsustainable aspects of our global economy: “Upon implementing NAFTA in 1994, the U.S. began to flood the Mexican economy with cheap government-subsidized corn, effectively driving millions of corn farmers (and others associated with corn production) off of their land.” Hence, the lyrics of this folk song shed light on the northbound movement of the borderland people and the need to rethink global consumption and its impact on both communities and ecosystems. Scholarship on folklore also shows intersections that inform twenty-first century sustainability concerns, like those outlined in the UNSDG. Ecocriticism allows for further investigations into the role of nature in this song, as do the UN’s sustainability goals, including Goal 8 on decent work, Goal 10 on reduced inequalities, and Goal 11 on sustainable communities (UNSDG).

Gorky Gonzalez is a folklorist of the region. His poetry addresses the paradoxes of life at the border region to reveal challenges with social and environmental injustices. In his poem Soy Joaquín (1968), Gonzalez defines corridos as the windows of his community’s collective memories of shared injustices:

“Tales of life and death, of tradition, legends old and new, of joy, of passion and sorrow of the people.”

“The oral traditions and literature that have emerged throughout the borderland region reveal twentieth and twenty-first century variations of neocolonialism and the effects of climate instability, which include ‘climate refugees’ (Oswald).”The oral traditions and literature that have emerged throughout the borderland region reveal twentieth and twenty-first century variants of neocolonialism and the effects of climate instability, which include ‘climate refugees’ (Oswald). However, communities along both sides of the border have collaboratively engaged to support sustainable alternatives (OER WordPress on Sustainable Living & Peace).

Activity: A Protest Song on Sustainability?

GOAL: To practice close-reading and identifying the theme of Woody Guthrie’s “This Land is Your Land” (1945).

OER Recording of This Land is Your Land by Woody Guthrie, 1945

INSTRUCTIONS: Listen & identify poetic elements: imagery, rhyme, assonance, consonance, and even figurative language. Now, build on initial impressions – try to identify and explain its theme. To navigate the theme of a song is an effort for most of us and one that we may not want to participate in if we want to simply experience songs from a distance. But think about the work of songwriters. Do you think the more effort they put into their compositions means that there is less joy for them to apply and develop their own talents? And, what if the theme of the song informs you about your culture?

What is the Structure of the Sonnet, as a form of lyrical poetry?

Outcome and Skills Practiced

Let’s learn more about poetry. An example is the sonnet, a form of lyrical poetry

- The word “sonnet” comes from the Italian word for “little song,” so many use not only rhyme and meter but other sound devices like assonance, interior rhyme, or alliteration to add to its inherent musical effect.

- Most forms contain fourteen lines structured in multiple stanzas of different length and rhyme scheme.

- Iambic pentameter is its most commonly used rhythm in the English language, meaning five iambic feet, totaling ten syllables per line.

- The Petrarchan sonnet contains an octave (eight lines) of the rhyme scheme ABBAABBA, and a sestet (six lines) which often varies in rhyme, but the most frequently seen schemes are CDCDCD or CDECDE.

- The Shakespearean sonnet contains three quatrains (four lines) with the interwoven rhymes ABAB CDCD EFEF and concludes with a couplet (two lines) GG.

- All sonnets use their structure to introduce a predicament or question and expand on its ideas and themes by the closing stanza.

- Poetic devices including imagery, figurative language, and allusions from classical mythology or scripture are often used to enhance a sonnet’s artistic or intellectual qualities.

Known as the ‘Father of Humanism’ at the advent of the Italian Renaissance Francesco Petrarch invented the sonnet form in the 1300s and by the 1500s sonnets became a prevalent form of lyrical poetry throughout theatrical works. Most sonnets, and poetry in general, address prevalent themes on love and loss, beauty and the turn of time, and philosophical meditations.

Activity: How to close read a sonnet?

GOAL: To practice reading poetry to build on critical thinking skills, to identify figurative language, & theme

DIRECTIONS: Explicate a stanza of Petrarch’s sonnet. *To explicate simply means to paraphrase line-by-line.

- First, read the sonnet a few times aloud and select a four-line stanza to paraphrase line-by-line

- Then, explicate each of the four lines and try to identify any figurative language and its purpose

- Lastly, explain how the stanza contributes to the theme of loss in the sonnet

She ruled in beauty o’er this heart of mine,

A noble lady in a humble home,

And now her time for heavenly bliss has come,

’Tis I am mortal proved, and she divine.

The soul that all its blessings must resign,

And love whose light no more on earth finds room

Might rend the rocks with pity for their doom,

Yet none their sorrows can in words enshrine;

They weep within my heart; no ears they find

Save mine alone, and I am crushed with care,

And naught remains to me save mournful breath.

Assuredly but dust and shade we are;

Assuredly desire is mad and blind;

Assuredly its hope but ends in death. Gutenberg’s Petrarch’s sonnet VIII

NOTE: Petrarch’s sonnet has a tone established through word choice and other poetic devices. Its tone addresses its theme on losing a beloved. Its tone can be described to be existential since it relates to existence.

Shakespeare’s sonnet XVIII [“Shall I compare thee to a summer’s day?”] and Edna St. Vincent Millay’s sonnet XXX [“Love is not all…”] also demonstrate themes on love and loss. Some early Renaissance sonnets were also meant to be satirical. Miguel de Cervantes’ plays have qualities of the ‘burlesque’, of humorous characterizations in a pastoral setting – rural, farming communities.

For example, like Shakespeare’s plays, Spanish drama is also in iambic verse. Cervantes’ first play titled Galatea (1585) demonstrates both its humorous qualities and iambic verse. The narrator’s complaint is on a young shepherdess who ignores his advances.

“What man will put his trust with might and main / In the instability / And in the change, pervading human things? / On hasty opinions time away doth flee…”(OER “Galatea,” a play by Miguel de Cervantes).

The fickleness of young women is critiqued in the quote above. The narrator’s ‘lover’s complaint’ of agonizing over wasted time due to the undecided character of female shepherdess. These lines also seem to offer a commentary on the fickleness of the entire human race.

Poetry in Western Literary traditions is quite vast and complex. Cervantes’ satirical verse alludes to a major trope which is further investigated in Chapter Nine on medieval proto-feminist Christine de Pizan – the literary trope of ‘the lover’s complaint’. In the European romances of her time, this literary trope emerges with conflict between men and women, which address the same concerns women have that launched the #MeToo movement. Current scholarship on this trope offers “to help students better understand discursive practices in the past and recognize the long histories of sexual violence and consent” (Holland and Hewett 2021).

How Does Non-Western Poetry Address Sustainability?

Outcome and Skill Practiced

In poetry, we can also witness a poetic merit, theme, and representation of nature and humanity. For example a poem by Sufi saint and mystic Nund Rishi states:

“Food will thrive only as long as the woods survive.”

Ecocritics identify literary works from many traditions around the world that bring readers back to the fundamental connections all life on earth has and must share. Rishi’s poem engages in a play with assonance between “food” and “woods” and ties nicely with the biological and ideological concept of the ‘web of life’: OER Sufism. This metaphor is helpful in projects on sustainability, especially on the need to build collaborations across cultures and national borders to address global concerns.

“Scientists, scholars, and politicians agree that we are in the midst of a global environmental crisis in which access to resources will become increasingly limited. In a time of crisis when human societies might cooperate and collaborate to reach a common resolution, the opposite may occur” (Ybarra 2009).

Ecocriticism allows for investigations of nature in literary works. What frequently emerges in works of literature are representations that treat nature as inferior or insignificant; it is an ‘other’. These depictions often reflect an ideology not too aware of or concerned with the heterogeneous biological framework of ‘web of life’. But instead an ideology that aligns binaries with hierarchical values and worldviews. Hence, an ideology that perpetuates perspectives of the physical world that all too easily fails to consider correlations between the health and well-being of people and of ecosystems and the nonhuman. Ecocritical literary studies identify how representations of nature can also serve as a platform to learn about ourselves and emerging themes that coincide with the UNSDG.

What Are Traditional Literary Tropes?

Outcome and Skill Practiced

Stories around the world have themes that are common across cultures and literary traditions, like familiar characters, the hero’s journey, and an anthropomorphized cosmos. These commonalities are literary tropes. Literary tropes are symbolic. They hold cultural meanings and references that reflect a particular culture’s experiences and worldviews, in addition to its universality.

A few literary tropes on character include:

- Mother figure as the giver of life and nurturer

- Father figure as a figure of permanence

- Trickster figures test key characters and serve in character development

- Monster/destroyer figures test heroes, as a rite of passage into maturity

A few literary tropes on theme include:

- A flood story that tells of the rise and fall of a kingdom

- The hero’s journey on a quest to find an empire, such as in the Epic of Gilgamesh, Epic of Sunjata of the Malinke people of West Africa, and Greek epic the Odyssey

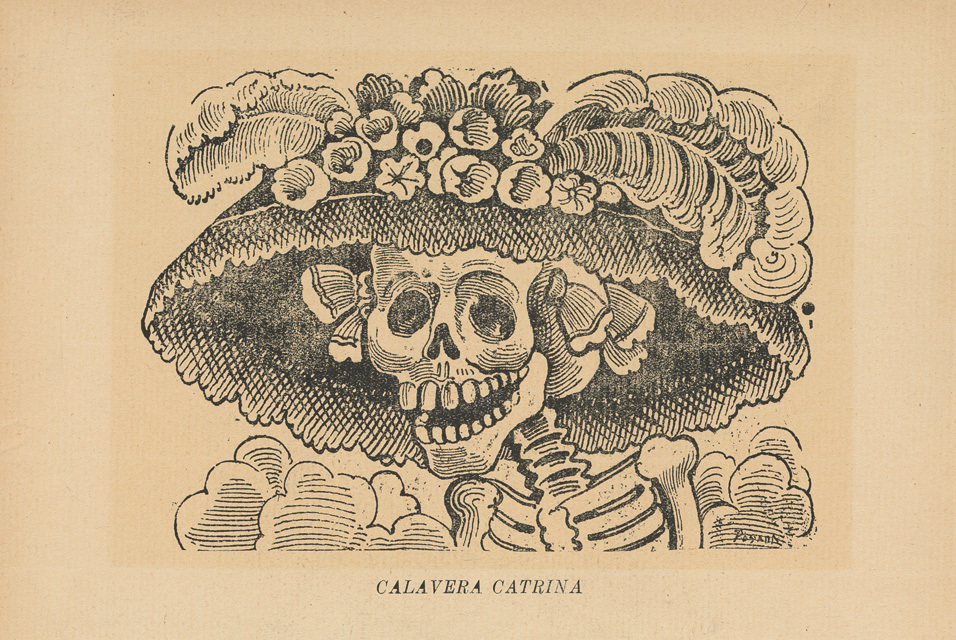

Other recognizable literary tropes are more closely associated with revered natural phenomena, the nonhuman: the moon, the sun, the milky way, rivers, mountains, and animals all hold complex symbolic meaning on the passage of time, birth, rebirth, permanence, and human behaviors. The symbolism of the human skull is a well-known object that appears across cultures as a symbolic trope. Its specific symbolic meaning varies due to the cultural norms of a people and its historical context. Skulls in literature may signify the life cycle or an existential perspective to explore human existence, like Hamlet soliloquizing to Yorick’s skull in Shakespeare’s Hamlet, Act V scene i.

St. Francis’ skull (left), Hamlet speaks to Yorick’s skull (center) & La Catrina Calavera (1910) by Guadalupe Posada. CC

Skulls in Mesoamerican and Western art and literature denote an awareness of earthly death, part of the cycle of life. Skulls also are religious tropes – like crosses, crucifixes, and fish, for Jesus of Nazareth. He signifies the renewal of the human soul in Catholic mythology. Another mythological story is Jason and the Golden Fleece where Medea’s rebirth ritual ensures Jason’s success; her talents are those of an Earth goddess (Jason & renewal ritual by Medea, Pressbooks). If we travel to Oaxaca, Mexico or view a Mexican film on Mexican cultural traditions, the skulls we witness represent a renewal ritual, too. For example, the religious festivities of The Day of the Dead in Mexico and Guatemala refer to the cycle of life and the passage to a new life. The living visit and speak to loved ones at nearby cemeteries; also an archetype on ‘nature’. Ecocriticism can inform on how these renewal festivals in the twenty-first century continue to be relevant in light of honoring the life of nature (Pressbooks on Latinx & Environmentalism).

Activity: On trope of Natural Phenomena, like the Human Skull

GOAL: To practice working with an emphasized object with symbolic significance with a quote from Shakespeare’s’ Hamlet. The scene is when Hamlet holds up the skull of a known deceased jester. Hamlet states that he has childhood memories with the jester. In the scene the skull closely aligns with Hamlet and his past. At this point Hamlet contemplates human desire and its contradictions with morality while holding the skull.

INSTRUCTIONS: A reading of Hamlet may offer insights on the presence of the skull.

“That skull had a tongue in it, and could sing once:

how the knave jowls it to the ground, as if it were

Cain’s jaw-bone, that was the first murder!”

The symbolic association of this skull in Shakespeare’s play contrasts with references to skulls in other literary texts and societies. Yet, the skull does represent a universal idea. We witness this profound object of human anatomy in other cultures and their literature – as it represents Hamlet’s contemplation of one’s morality in the face of contradicting desires.

Media Attributions

- Saint Francis of Assisi © Wellcome Collection is licensed under a Public Domain license

- José Guadalupe Posada © Store Norske Leksikon is licensed under a Public Domain license

Folklore are short stories in folk communities, especially from the peasantry: animal fable, animal-bridegroom tales, parables, legends, allegories, trickster tales, and myths associated with nature like solar myths. Their roots are closer to spoken tradition rather than in print. Yet, early printed versions – like chapbooks – do ‘reshape’ earlier versions or even add a specific perspective. The most famous example is the 1706 first English translation of an earlier compilation of stories, The Arabian Nights. Folklore includes fable, legend, mythological stories, chronicle (iambic trimeter, Greek versions from 140 CE), to gloss, animal fables (India, Aesop), orphan stories and plot motifs. Folklore Studies looks into unofficial, oral, traditional forms of expressed culture – in art and in literature, for example. But also expands to folk music, jokes, and events, like festivals. The rich traditions that folklore encompasses – either in ancient Greece like Aesop’s fables and the storytelling traditions within Native American social groups and can be differentiated by more recent technologies of print and digital media. Yet, the differentiations become difficult in the twenty-first century due to the mixing and blending of traditions – a highly studied phenomena with roots in ancient travel journals, 1700s forms of European ‘Orientalism,’ and postmodern acculturation.

Poetry is a literary genre and the sonnet is one of its subgenres - others are the ballad, lyrical poems, and epic poem, among others (OER Pressbooks). The practice of designating genre comes from Western literary traditions led by Greek thinkers like Aristotle. (On "How to Read Poetry" OER)

Indigenous communities is a proper noun that refers to the peoples who have lived throughout North America for over 10,000 years, where they historically call Turtle Island. This territory reaches beyond the borders of today’s Canada and the United States. Hence, Indigenous communities are the “descendants of those who survived the colonizing apocalypse that started in 1492 and continues today” (Justice 2018). They affirm their “the spiritual, political, territorial, linguistic, and cultural distinctions” throughout numerous and varied tribes. Indigenous communities experience stories and their ancestral lands as crucial to the survival of their culture and heritages. They learn and share the world by storytelling, including oral traditions on science, medicinal biological knowledge, and religious rituals. The capitalization of the word Indigenous “affirms a distinctive political status of peoplehood” with agency (Justice 6).

According to ecocritic Lawrence Buell’s definition of ecocriticism, which involves the philosophical view that “human being and human consciousness are thought to be grounded in intimate interdependence with the nonhuman living world,” this “interdependence” is the web of life (Buell 2011). According to Danel Wildcat and Dine Deloria Jr. – whose son is currently History faculty at Harvard Dr. Philip Deloria (wiki on Philip Deloria), the worldview, the metaphysics of Indigenous peoples in North America experience reality as ‘related,’ the world is unified, and all aspects have significance and share a commonality among the tangible, spiritual, intelligent, and intangible. “The teachings of the tribe are almost always more complete, but they are oriented toward a far greater understanding of reality than is scientific knowledge”(OER Pressbooks on Indigenous Education, go to Ch. 9). As a more thorough and intuitive philosophy, they expose the limitations and exclusionary culture of Western culture and its reliance on Cartesian dualistic philosophy: “We live in an industrial, technological world in which a knowledge of science is often the key to employment, and in many cases is essential to understanding how the larger society views and uses the natural world, including, unfortunately, people and animals.”

A literary trope is a recognizable plot element, theme, or visual cue that has figurative meaning. It can appear within the body of an author’s work, within a tradition, and across cultures as witnessed in world literature and world mythology. A common literary trope is the hero’s journey, which is a plot structure found in stories all around the world. Many literary tropes may not be universally understood, but occur commonly within a specific tradition – like in gothic and fantasy literature, and also in popular comics. Another recognizable literary trope that is observed in Western letters is the symbolism of skulls, like the skull Shakespeare’s Hamlet holds when he delivers his “Alas poor Yorick” soliloquy. In this scene, the skull represents a contemplation of one’s morality in the face of contradicting desires. Yet, as a religious Catholic trope a skull is associated with Jesus of Nazareth, for example. This association may signify more directly with death. Yet, in most religious contexts, skulls are associated with the life-cycle. For example, a skull in Mexican cultural traditions represents this meaning, through rituals associated with the Day of the Dead. They involve visiting and speaking with the deceased at nearby cemeteries, among other rituals; here, the skull signifies the life-cycle. The skull may also share associations with the serpent, like in Chinese and Mesoamerican traditions. Yet, the ‘serpent’ in most Western texts –the New Testament, Ovid’s Medusa, and even popular texts like Harry Potter – is usually associated with demons and the unholy, a finite view of the life-cycle. Another literary trope common in European literary texts is the color ‘white’. In many instances this color means death when associated with snow. Witnessed in James Joyce’s 1914 story “The Dead” from Dubliners, snow is a metaphor that signifies the death of a beloved and of a marriage (Wiki on Joyce's "The Dead" from Dubliners).

Popular children’s literature is understood in contrast to Daniel Heath Justice’s explanation of folkloric traditions.

Being “too diverse and multifaceted“ and not a fixed artifact on “‘the total output of a people,’ [literature] is an expansive, dynamic, adaptive thing; that’s part of its beautiful, terrible power. It serves the powerful and the powerless alike,” according to Cherokee First Nations and Indigenous scholar Daniel Heath Justice (Weaver qtd. Justice 21). Indigenous literature involves the ways “Indigenous peoples have always communicated ideas, stories, dreams, visions, and concepts with one another and with the other-than-human world.” This literature reflects an Indigenous metaphysics: “The best description of Indian metaphysics was the realization that the world, and all its possible experiences, constituted a social reality, a fabric of life in which everything had the possibility of intimate knowing relationships because, ultimately, everything was related” (WordPress "Power and Place," 2001).

Oral tradition involves performing somatic and linguistic cultural codes as a dynamic visual art. These performances involve dancers dressed in sacred clothing with symbolic significances, along with music and dynamic jestering. A social group’s oral tradition is maintained and related through memory and referential communication to make meaning. Social groups communicate their people’s legacies of known institutions for the present generations to learn from and preserve. Oral tradition as performance addresses known understandings of astronomical, cosmic phenomena, biology of fauna and flora, especially about their medicinal and nutritional properties, refer to geographic locations and seasonal phenomena, relate political history and treaties, reflect on philosophical and religious storytelling traditions, and perform rituals on current technologies. Scholars like John Miles Foley point out that once an orally delivered text is written down, its original version has been “reduced,” of a once-living experience to one of bureaucracy, forever eliminating much of its meaning. Oral traditions dwarf written literature in both size and diversity (Foley Native American Oral Traditions).

Ancient literature is known as the earliest forms of writing systems and their technologies like cuneiforms, hieroglyphs, codices (plural of codex), and alphabetic symbols.

The theme of a narrative or a play is the general idea or underlying message that the writer wants to expose. In Elizabethan Theater, “John Milton states as explicit theme of Paradise Lost to 'assert Eternal Providence,/And justify the ways of God to men.' Some critics have claimed that all nontrivial works of literature, including lyrical poems, involve an implicit theme which is embodied and dramatizes in the evolving meanings and imagery” (OER Elizabethan Theater). Whether you define it as the overarching subject matter of a text or its message, identifying themes in literary studies establishes initial skills in describing, summarizing, and offering a commentary to a piece of literature, without additional theoretical approaches. Yet, some research is helpful - of its historical era, culture, and geographic region.

Identity formation is understood in Ethnic Studies through “The passage of knowledge and culture from one generation to the next…” (Kennedy and Bermio). Visit Key Terms for more details and resources.

In literary texts, in common speech, and in performative pieces like poetry and theater, metaphor is a form of a figure of speech where two or more elements of a different nature are compared with each other, but without “like” or “as.” If the comparison includes “like” or “as,” this form of a figure of speech is known to be a simile.

A concept that encompasses the dynamic and intricate network of how humanity affects communities, the environment, and climate. Current efforts to address a wide array of cultural and sociological practices that are all interrelated and connected to seriously address the causes and effects of ‘climate instability’ and other injustices that plague some societies while threatening the rest. The United Nations offers 17 goals of development to highlight many facets of society – from the production of goods and treatment of women and the impoverished and social justice and renewable energies (UNSDG ). Yet, current scholarship by ecocritics in literature emphasizes the fundamental need to address today’s crisis – a sustainable ideology, to demystify human and nonhuman binary thinking. Where we as a global people realize that we are interconnected to local and global ecologies. This worldview can also demystify current human tendencies of placing humanity above the nonhuman. An example of this argument is witnessed in Frank Boom’s ecocritical analysis of Ovid’s Metamorphosis, Book 10 and 11, on the mythological tales of “Orpheus and Cyparissus” (OER Article on Today's Climate Crisis & Ovid's "Metamorphoses").

(“eco” in Greek is household, ecology is the learning of the life of populations)

What is ecocriticism? At first sight, it is simply a literary theory to learn about nature in literature; when critics approach literature to learn about nature, they are offering ‘ecocritical’ interpretations. Ecocriticism aims to not reduce nature into a concept or social construct, which the Western tradition shows in the majority of its literary traditions. Literary studies offers a platform to learn about representations of nature in texts, while analyzing themes on social injustices, which may share similar treatments, since “ecocriticism is a theory that seeks to relate literary works to the natural environment” (Estok 2005). Another explanation is “the study of the relationship between literature and the physical environment” and “takes an earth-centered approach to literary studies” (Glotfelty and Fromm 1996). Another explains that, “Ecocriticism examines the representation of and relationships between the biophysical environment and texts, predominantly through ecological theory” (Chisty 2021). Since the 2000s, ecocriticism has relied on scientific and philosophical approaches to understand humanity’s place in the world. The UNSDG offer a wide-ranging view of aspects of human’s roles to address current injustices and the climate crisis. Partly, it is “committed to effecting change by analyzing the function – thematic, artistic, social, historical, ideological, theoretical, or otherwise – of the natural environment.” Ecocritical readings on environmental injustices can intersect with social injustices, like Langston Hughes’ poem expresses. *Go to the section on Langston Hughes’ poem A Dream Deferred in the introduction of this book. This class supports intersections between social injustices and environmental ones. The work of Joni Adamson, American Indian Literature, Environmental Justice, and Ecocriticism: The Middle Place (2001) features the literatures of Indigenous communities and literary analyses with ecocritical understandings to address and expose Western abuse of nature and the causes of our current environmental crises, while demonstrating the literary and storytelling traditions of Indigenous communities as ‘an alternative’ theory. For more information, visit OER on Ecocriticism. This literary theory stems from the first wave of environmentalism in the U.S. by ecofeminism. The term ecocriticism emerged in the article Literature and Ecology (1978) by William Rueckert and an earlier work in 1972 by William Meeker The Comedy of Survival: Studies in Literary Ecology. “First wave" environmental criticism concerns itself with conventional nature writing and conservation-oriented environmentalism, which traces its origins to the work of Ralph Waldo Emerson, Henry David Thoreau, and John Muir. "Second wave" environmental criticism redefines the environment in terms of the seventeen Principles of Environmental Justice and increasingly concerns itself with "issues of environmental welfare and equity" and "critique of the demographic homogeneity of traditional environmental movements and academic environmental studies” (17 Principles of Environmental Justice). A modern third wave of ecocriticism recognizes ethnic and national particularities and yet transcends ethnic and national boundaries; this third wave explores all facets of human experience from an environmental viewpoint” (Adamson 2009). Originally, ecocritics looked at the relationship between literature and nature – between culture and the global environment. Literature shows human tendencies to anthropomorphize nature. Ecocritics see culture as hierarchical and in contrast to nature, especially in Western texts. To analyze this relationship, nature needs to be distinct from human constructs: the wilderness, scenic sublime, countryside, and domestic picturesque. Man-made factors are social orders and political constructs like culture and poverty. Yet, the ‘setting’ of narratives may also be fantastic – as in folklore, the gothic, and science fiction, and hence is also fertile soil for ecocritical readings. Ecocriticism takes as its subject the interconnections between nature and culture, specifically the cultural artifacts of language and literature. As a critical stance, “it has one foot in literature and the other on land; as a theoretical discourse, it negotiates between the human and the nonhuman" (Glotfelty and Fromm qtd. in Sandner 2000). The roots of the environmental movement can be traced back to the abolition movement, which revealed the connections between colonization, conquest, slavery, resource exploitation, and capital, and many of the most successful strategies of early environmentalism were borrowed from the abolition, civil rights, and women's movements and American Indian Land Claims lawsuits. For this reason, “any history of environmentalism that did not include W. E. B. Du Bois, Rosa Parks, Martin Luther King, Jr., or Cesar Chavez, among others, would need to be revised” (Adamson 2009).

The EPA (Environmental Protection Agency) defines environmental justice as “the fair treatment and meaningful involvement of all people regardless of race, color, national origin, or income, with respect to the development, implementation, and enforcement of environmental laws, regulations, and policies (wiki). The 17 Principles of Environmental Justice in 1991 reflects the work and experiences of those who live in communities where toxic waste has decimated their ecosystem. For more information, visit OER Pressbooks on Environmental Justice.

Jean Paul Sartre is known to have first recorded use of the term neocolonialism. “It was described as the deliberate and continued survival of the colonial system in independent African states, by turning these states into victims of political, mental, economic, social, military and technical forms of domination carried out through indirect and subtle means that did not include direct violence. With the publication of Kwame Nkrumah’s Neo-colonialism: The Last Stage of Imperialism in 1965, the term neocolonialism finally came to the fore. Neocolonialism has since become a theme in African philosophy around which a body of literature has evolved and has been written and studied by scholars in sub-Saharan Africa and beyond” (Internet Encyclopedia of Philosophy).

Pastoral in Western works of poetry, for example, often present nature as an ideal place and a refuge from unnatural modern urbanization. Visit Key Terms for more details.

Claiming to be greatly influenced by Greek and Roman traditions, the Western literary tradition also reflects Arabic scholarship that includes the East – along with its technologies and cultural exchanges – and Indo-European linguistic traditions throughout Europe and its colonized territories – like the Americas – known as the romantic languages. This excludes Indigenous peoples and Slavic; yet, semitic language, religious thought, and near East influences are part of the Western tradition.

Scholarship on the #MeToo movement and its impact in literary studies focuses on transformative learning. For example, recent scholarship on medieval European literature on social constructs of gender as an unequal binary focuses on how its contemporaries responded. For 21st century learners, one strategy to address systemic inequality is to literally write yourself in, as Pizan has done, to address misogyny. Another strategy is to engage through student-centered inquiries like, “What does it feel like to be excluded from a literary tradition?” and “What are the strategies to write your way back in?” These approaches focus on the absences or, as Christine de Pizan’s work shows, the misrepresentations of gender in literary works (Torres, McNamara qtd. in Holland, Hewett 326-327). In the case of Pizan, traditions of misrepresenting women within the established hegemonic order of a superior and inferior framework are addressed to advocate for reforms.

The concept of nature is a social construct with qualifiers that make nature idyllic, or ‘balanced.’ Yet, in non-Western literary traditions, references to nature reflect real lived experiences, immersed in nature. For example, in Indigenous oral traditions, nature is dynamic. Adamson explains, “They tell of wars, crisis, and famine…they learned to live with ambiguities, to see the patterns, and to mimic natural processes in the cultivation of their gardens” (Adamson 56). Ecocritics and environmental humanists, among other scholars, witness humans as also a social construct in opposition to nature, or the nonhuman, which is witnessed throughout literature. Instances of the feminization of nature are understood as gendered ethnocentric views of nature by those who define humanity as superior to nature, and the masculine gender as superior to the female gender. These social constructions suggest anxieties about what it means to be human and overlap with discourses on power and colonialism when the colonized are effeminate, along with the conquered landscape. The gendering of a people and nature acts as a mechanism that initiated modernity, inequalities ecofeminist Soper addresses, “given the widely perceived parallels between the oppression of women and the destruction of nature” (Soper 1995). Feminist philosopher Kate Soper also argues on how nature is an ‘otherness’ in What is Nature: Culture, Politics, and the Non-Human (1995) to focus on Western attitudes from two schools of thought, on ecology and cultural criticism - that of our current climate crisis and efforts to address this crisis while understanding “the politics of the idea of nature,” on the semiotics of ‘nature’. Intersections between perception of nature and theories of sexuality offer insights into ‘the politics of the idea of nature.’

“A more or less systematic ordering of ideas with associated doctrines, attitudes, beliefs, and symbols that together form a more or less coherent philosophy or Weltanschauung for a person, group, or sociopolitical movement” (APA Dictionary qtd. BU Equity Guide). In schools of thought such as political science and psychology, ideology is addressed as a system of beliefs that underpins and sustains the form of a society. A school may be supported by an ideology of curricular vigor that rewards certain achievers. The economy of a country may be supported by a capitalist ideology. But, ideology is also understood through other worldviews and cultural norms, like those practiced by the Indigenous communities of the Americas.

Health and well-being is Goal 3 of the United Nations Sustainable Development Goals (UNSDG). Visit Key Terms for more details.

The hero’s journey is thoroughly examined in The Hero with a Thousand Faces (1949) by Joseph Campbell. Campbell examines the literary trope of the epic hero throughout world mythology. Visit Key Terms for more details.

A symbol is an object, expression or event that represents an idea beyond itself. The weather and light/darkness will often have a symbolic meaning. Survey of Native American Literature: Symbols in Literature

are stories are woven together to give an impression of narrative cohesion, like the Epic of Gilgamesh and Biblical Torah. Visit Key Terms for more details.