Chapter Eight: Lyrical Poetry & Poetic Fragments of Greek Poet Sappho & Intersections with Reducing Inequality, Gender Equality, Sustainable Communities, & Decent Work

Outcomes and Skills Practiced

- Chapter 8 builds on previous activities: on poetic devices, figurative language, and allusion.

- To succeed, select several assignments to continue to practice analysis of Sappho’s lyrical poetry while you consider an ‘ecocritical’ approach to literary studies in poetry.

On Lyrical Poetry & Its Early Origins in Sappho’s Work

Earlier works on poetry and epic poems featured in Part One — like those by Enheduanna and the mythological epics by Indigenous communities of North America — are not personalized in the same way as lyrical poetry. Epic narratives, even most of Enheduanna’s hymns, operate within the context of the sociopolitical climate of the eras which they represent.

For an example, review Chapter One of Part One and closely read Enheduanna’s hymn, which reflects her role as the daughter of the empire at times of its expansion and the opposition’s uprisings.

It was in your service/That I first entered/The holy temple,

I, Enheduanna,/The high priestess,/I carried the ritual basket,

I chanted your praise./Now I have been cast out/To the place of lepers.

Enheduanna’s verse shows ways to neutralize conflict while in exile and through the blending of goddesses in her verse.

In the Western tradition, early, ancient origins of lyrical poetry are attributed to ancient poets like Sappho. Her poetry derives from ancient Greek religious cult traditions, yet her verse also reflects personal desires and perspectives.

Sappho lived during the archaic era of Greece (800–450 B.C.E.>) when early Pre-Socratic Greek philosophy emerged and prior to classical Greece, an era when the idea of democracy became known in Athens by 400 B.C.E. Sappho lived from about 630–570 B.C.E. on the Isle of Crete, Lesbos in the Mediterranean. She follows Homer by 200 years – he wrote down the ancient Greek epics The Iliad and The Odyssey in 800 B.C.E. These epics were part of ancient Greek oral tradition of the thirteenth century B.C.E. Sappho’s contribution includes Aeolic verse (an example of a poetic device).

Sappho, also known as Psappho, also wrote in the vernacular of her region, the Isle of Lesbos. Her lines of poetry are rich with imagery, follow a structured rhyme scheme, and develop the voice of the narrator.

Activity: What does your close reading reveal about the metaphor and nature in Sappho?

GOAL: To continue to build expertise in textual analysis in comparative literature on poetry with ecocritical approaches and to also address anthropomorphism.

DIRECTION: You must do an analysis of two fragments attributed to Sappho below:

…heavenly summit of the mountain descending (LP. 2.1A)

There are meadows, too, where the horses graze knee deep in flowers, yes, and the breezes blow here honey sweet and softer… (LP. 2)

- Closely read for imagery and word choice, and identify the use of figurative language.

- Then, address the representation of nature.

- In contrast to the hymn by Enheduanna, what do you learn about lyrical poetry through Sappho’s lines of poetry?

- Ecocriticism centers on the status and health of nature, the nonhuman aspects of the physical world.

- Can you make an argument that Sappho treats nature through anthropomorphism or does her treatment of nature present another way to relate to aspects of the physical world?

On Sappho’s Lyrical Poetry and the Western Tradition

Traditions of lyrical poetry cover many geographic regions and cultures, including Western culture — especially when the Greek language was the lingua franca throughout the region and parts of Europe, and the Middle East, Egypt, and Persia from 323 B.C.E. with the rise of Alexander the Great and the fall of the Roman Republic in 25 B.C.E., and by Augustus to the Middle Ages in the 1400s.

Greek lyrical poetry is associated with music. ‘Lyric’ implies a musical instrument, the lyre, was used. In our times, we know the words of songs to be the ‘lyrics’. This is an indication of how early ancient traditions have been absorbed into recent ones. Among the classical poets like Hesiod, Horace, Virgil, and others, Sappho was the most admired in her time. Homer simply called her ‘the poet’.

This example of the work of Greek poetess Sappho shows the essence of lyrical poetry.

“The Moon is down

The Pleiades. Midnight,

The hours flow on,

I lie, alone.”

With few poems that allude to contemporary political topics, the majority of Sappho’s poems reflect the religious cult she was part of and her role as an educator to young unmarried women, before they are betrothed.

Here, you take a garland now also,

Cypris: gracefully in goblets of gold mix nectar

with the gladness of our festivities and pour the libation… [LP. 2]

These poetic lines give agency to the speaker and to the speaker’s experiences.

Her lyrical poetry reveals personal, everyday events, including her poem that asks the Greek Goddess of Love to return her brother’s wife to deter his mistress.

Aphrodite, Cyprian, let her find you at your prickliest: do not let Doríkha crow about him coming a second time to the love she is missing…[LP. 15]

Sappho’s contribution of the four-line stanza where the last line has only five syllables is known as Adonic. But these lines also show how Sappho’s poetry is personal and autobiographical, which is the essence of lyrical poetry — on the experiences of the poet and not simply to praise deities, as seen in other forms like the hymns of Enheduanna.

For example, Sappho’s evocation of Aphrodite shows a personal perspective on love and loss:

Come to me even now, and from my hardships free me

and from my cares, and all the things to bring about

my heart desires, bring about for me. And you,

fight here beside me.

The lines of verse below is Aphrodite’s response to the narrator’s pleas in Ode to Aphrodite (Pressbooks).

And what most of all my heart wished to have

in my troubled way.

“Who is it this time I’m to turn back to your favor?

Who hurts you now, Sappho dear?

Lyrical poetry are poetic works that reflect personal experiences and ideals about commonplace events. The vast geographic regions where lyrical poetry became its own tradition covers the Mediterranean — especially Greece and Rome, but reached Egypt and Mesopotamia — beyond Persia, Turkey, and the subcontinent of India, including Asia Minor — a region known in Greece as ‘the East’.

According to early records, the emergence of lyrical poetry occurred from 600 to 400 B.C. E., particularly at the advent of the Hellenistic era of Greece and that of Rome by 31 B.C.E.The far-reaching campaigns of Alexander the Great mark this era as a time when the arts and sciences were shared, and religions were intermingling. The first Christian Bible was written in Greek, which demonstrates influences of Judaism and Greek culture at a time of the Roman empire when Latin started to become the lingua franca of the Mediterranean. The influences of early Greek traditions of classical lyrical poetry are seen in Rome, early modern Europe, Romanticism, and the Victorian eras.

Lyrical poetry differs from epic poetry in its short length with an indistinguishable narrator on personal day-to-day experiences. Leading lyrical poets pay homage to earlier poets and their works, including the innovative lyrical verse by Sappho.

For example, a leading method of locating fragments of Sappho’s poems is due to later generations saving her work by incorporating her poetry onto documents that honor special occasions and events like weddings and festivals. Each tradition reflects its own version of lyrical poetry at a specific time. Other traditions of lyrical poetry show its own distinct forms; yet, certain poetic devices continue, like the allusion.

The English lyric of Geofrey Chaucer shows a desire for a poetry that lacks French influences in the mid-1300s. This is demonstrated in Chaucer’s “The Franklin’s Tale”:

He seyde he lovede and was biloved no thyng (He said he loved and was in no way loved in return).

Yet, his work also reflects the inclusion of classical allusion, which the reference to Narcissus shows.

And dye he moste, he seyde, as dide Ekko

And he must die, he said, as did Echo

For Narcissus, that dorste nat telle hir wo.

For Narcissus, she who dared not tell her woe.

On Sappho and ecocriticism

Eros is a well known lyrical poem attributed to Sappho who is associated with passion and the Earth goddess Gaia in Hesiod’s Theogony (800 BCE). In different Greek mythological traditions, Eros is both the son of Chaos and Aphrodite (Gutenberg’s “Theogony”). Representing intense desire, Eros binds fertility and growth in nature. According to Ryan Tribble — a scholar in Greek Classics and ecocriticism,

“For the ancient Greeks, perhaps the nearest conceptual equivalent to a generalized understanding of ecology is Eros, the god of desire and the unifying impulse that binds organisms together…” (Tribble 2022).

Identified with aspects of nature, Eros reflects the characterization of unifying “organisms together,” witnessed in Sappho’s poem.

My dreaming eyes saw Eros from afar/Coming from heaven in his mother’s car,/In purple tunic clad; and at my heart/The God was aiming his relentless dart (Sappho’s Eros).

Sappho’s version of Eros places human desire within nature itself, which contrasts the Roman version of Eros, known as Cupid. His darts of desire represent human erotic desire.

On Sappho and Sexuality

Sexuality in Greek culture is well-known in Classical Studies. “The First Kiss” is a poem by Sappho that expresses the initial stages when people start to mature away from childhood innocence to passionate desire.

Her mouth for immolation

Was ripe, and mine the art;And one long kiss of passion

Deflowered her virgin heart.

Scholarship on poetry of Sappho and attention to themes on same-gender attraction and same-gender relationships arose in recent twentieth-century studies. Most scholars of Greek antiquities and Sappho’s poetry argue that identifications of her sexuality may be a modern practice rather than how sexuality was understood in her time (On Sappho and sexuality). By the absence of female-based sexualities, more work needs to be done, as critics on Michel Foucault argue.

Foucault makes no mention of Greek female homosexuality, despite its established place in the history of Ancient Greece. He does not refer to any Greek poetry, literature, art, or mythology in the context of their portrayal of either a fictional or actual female homosexual relationship. Foucault’s writing this leaves us wondering how the works of Alcman or Sappho, Aristophanes’ speech in Plato’s Symposium, or the myth of Callisto figure into his vision of a sexuality defined by the strict dichotomy of active and passive without regard to gender. (On Sappho and sexuality)

On Lyrical Poetry & the Epic

Distinctions between the epic narrative poem and lyrical poetry are helpful. They usually differ in length and perspective. The epic poem is a lengthy, episodic narrative in verse that tells the stories and heroes of a people. The epic — like the Epic of Gilgamesh and Popul Vuh — also reflects socio-political themes. Written in verse, the hero’s journey in the Epic of Gilgamesh demonstrates concerns about natural resources and the building of its empire and the success of the Twin Heroes’ journey from the underworld to reclaim their father in the Mayan Popol Vuh represents the creator of humanity as agriculture. Lyrical poetry is usually shorter in length and is not necessarily a narrative. In many instances lyrical poetry addresses secular concerns. Its themes range from love and loss to unrequited desire and the mourning of those lost in battle or on the plight of unjust events, including forms of laments, odes, elegies, and ballads. Lyrical verse addresses more personal imaginings and the agency of a poet. Yet, the literary epic blends both aspects of the traditional epic and personal worldviews. The literary epics of Dante Alighieri and John Milton are epic narratives with religious yet personal perspectives.

Activity: How do John Milton’s lines of poetry reflect both epic and lyrical poetry?

GOAL: To gain practice in identifying aspects of the epic and lyrical poetry in poetry

DIRECTION: For example, epic and lyrical poetry is demonstrated in heroic poetry.

Read the two lines from John Milton’s literary heroic epic Paradise Lost (1667).

Focus more on tone and less on imagery to witness its elevated theme on religious devotion.

“Through Heav’n and Earth, so shall my glorie excel,

But Mercy first and last shall brightest shine”(Milton iii line 132-133) Gutenberg’s “Paradise” Lost by Milton

Unlike the traditional epic narrative, these lines show Milton’s own personal treatment of religion, an aspect of lyrical poetry where everyday events and experiences resonate through the narrator in the poem. These lines are more telling once we learn that Milton’s first published poem in England was on William Shakespeare, whose genius he honored and celebrated in his own poetry so much so that readers can understand Milton’s poetry as both religiously devout and artistically informed by a variety of literary traditions, including Elizabethan drama and poetry.

“What needs my Shakespeare for his honoured bones,

The labor of an age in pilèd stones,

Or that his hallowed relics should be hid

Under a star-pointing pyramid? (Milton 1630)”

The opening four-line stanza of John Milton’s sonnet titled On Shakespeare is an example of lyrical poetry, in that the poetic devices of rhyme, rhythm, alliteration, and metaphor are driven by a narrator and resonate with an individualized perspective. Throughout his life, Milton resisted restrictions on free thought and any tendency by the Church of England to dictate personal devotion and religious agency.

On Lyrical Poetry on Race

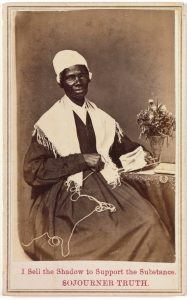

The lyrical poems by abolitionists blend values of human rights with social justice to share their personal experiences in antebellum American South. Although not known to have written down her own poems and songs, works attributed to abolitionist Sojourner Truth were published in newspapers, during the American Antebellum era in the 1850s. Her lyrical poems address politics and religion.

Activity: How does Truth’s song blend personal tone with social shared experiences?

GOAL: To work with more recent lyrical poetry that blends the personal with socio-political topics and experiences.

DIRECTION: For example, to demonstrate the blending of the personal and the socio-political in abolitionist lyrical poetry, read these lyrics by Sojourner Truth. While her song directly engages with the plight of her people and her role as an abolitionist, Truth’s song also shows a personal tone that is rhetorically effective — interestingly, one that resonates by honoring collective experiences.

She sang the following original song at the close of the meeting —

‘I am pleading for my people—

A poor, down-trodden race,

Who dwell in freedom’s boasted land,

With no abiding place.’

Witnessed in her lyrics, Truth’s song indirectly suggests unjust events from both personal experiences and those of other Black Americans. The historical allusion also exposes contradictions in American democracy. Claiming an American ideology of civil liberties and basic human rights, Sojourner Truth’s song reminds audiences that all Americans are implicated in the institution of slavery.

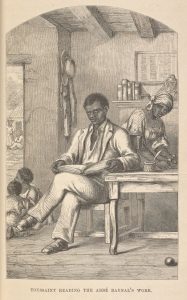

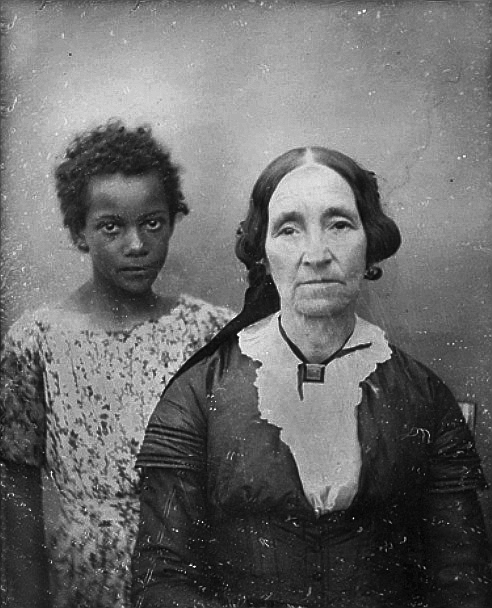

Toussaint L’ Overture, Girl with Elderly woman in New Orleans, & Portrait of Sojourner Truth CC

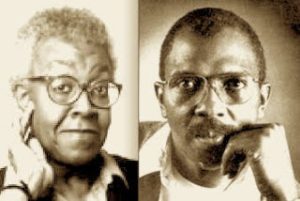

The poetry of American poet Etheridge Knight addresses twentieth century experiences and versions of racism and unjust institutions, such as prisons, and systemic racism. Born in Mississippi, Etheridge Knight lived and wrote poetry in Kentucky and Indiana, served as a Medical Technician in the Korean War, and taught at Boston’s Roxbury Community College in the 1980s. Themes on social injustice blend with commonplace experiences throughout his lyrical poetry. By referencing nature in his poems, his work imagines a people’s legacy of enduring and suffering racial inequalities. Knight also reinvents domestic and known landmarks in his poem, through representations of nature and references to landmarks.

For example, elegiac metaphors in the poem The Bones of My Father by Etheridge Knight represent both our interconnectedness with nature and the unsustainable plight of Jim Crow South.

There are no dry bones

here in this valley. The skull

of my father grins at the Mississippi moon

from the bottom

of the Tallahatchie,

the bones of my father

are buried in the mud of these creeks and brooks that twist

and flow their secrets to the sea. (Black Voices from Prison 1971)

Metaphors, nature, and references to his father converge to unveil personal and socio-political experiences on themes of social justice. Bones do not “dry” to disappear. The “skull” always sees the turn of day and is integrated into the rhythms of nature, the “moon.” The “bones” of his father are deep within the “Tallahatchie” river, a sense of permanence is established as their suffering’s “flow” into the sea.

Knight blends local folklore with the permanence of natural phenomena to highlight his own experiences and those of his people — of his father who lived under the Jim Crow South and those who have been direct targets of white supremacist hate and violence, like Emmett Till, the 14-year-old whose lynching resulted with in his body tied to a cotton gin and thrown in the Tallahatchie River, Mississippi, in late August of 1955. The story of Emmett Till is one example of “secrets” that flowed out to sea.

On Lyrical Poetry on Race Intersects with Social Justice, via Ecocriticism

Ecocriticism enhances the current meanings of Knight’s references to nature in the poem The Bones of My Father, on its reference to the Tallahatchie River. The intersection of systemic racism with the history of a Southern state like Mississippi in an ecocritical approach offers insights about the life of Emmett Till and his significance to Black Americans and peace and justice in Knight’s poem.

For example, in 2009, the river became a Civil War landmark in the state of Mississippi due to a battle between the American North and South in late 1862. Mississippi was second to South Carolina in joining the Confederacy in January 1861 (History of Mississippi & the Tallahatchie River). Yet, Etheridge Knight’s reference to the Tallahatchie River also places this natural waterway in a twentieth-century context with its allusion to the historical Emmett Till.

An ecocritical approach also places the Tallahatchie River at the foreground of the poem’s realism. The Tallahatchie River has had and continues to have significant resonance in legacies of racism and social justice for the Black community and concerned Americans, due to the lack of accountability for hate crimes targeted at the lives of Black Americans and their communities. Like Sojourner Truth’s song that signifies the voices of the Black community, Knight’s poem also symbolizes the collective. The association with Tallahatchie River connects the stories, fates, and “secrets” of persecuted people. Emmett Till is part of the Black community’s legacy. Collectively, their histories and stories in Knight’s poem honor and reach for social justice. This is demonstrated by the symbolism of the skull.

The skull/of my father grins at the Mississippi moon

In the poem, the river is between the moon and sea and is the carrier of “secrets” out to the ocean. Carried by the forces of nature the secrets reach the world’s oceans, while the father’s bones remain — perhaps to also serve as a landmark to inspire stories and poems: folklore. The symbolism of the father’s skull proposes justice to show that “secrets” of profound significance and weight cannot sink but remain visible and told. The representation of nature ensures justice.

Lyrical poetry also has an underlying moral ethos that is personal yet universal, experienced through the first person yet collective, which may reflect religious doctrine on secular concerns. Like Etheridge’s poem, lyrical poets respond to lived events by addressing the cosmos.

For example, lyrical poetry as folkloric ballads by Harlem Renaissance poets blend local memories with representations of nature. Observe how foreboding is created by the placement of the Black girl and sun at dusk:

Her skin is like dusk,

O can’t you see it,

Her skin is like dusk,

When the sun goes down.

In Jean Toomer’s folkloric ballad, from his expressionist story-cycle Cane (1923), the Black girl’s skin is determined by representations of the cosmos. And in folklore, when the sun sets it is an omen that symbolizes danger. An ecocritical approach recognizes the value of nature in Southern Black culture. Like Knight’s poem, cosmic forces are also represented to honor its life-giving roles. In Toomer’s song, this folkloric ballad hints at the fate of Black lives, due to obsessions about skin color in the story that follows this song, “Blood Burning Moon,” which is about Black defiance and white supremacy.

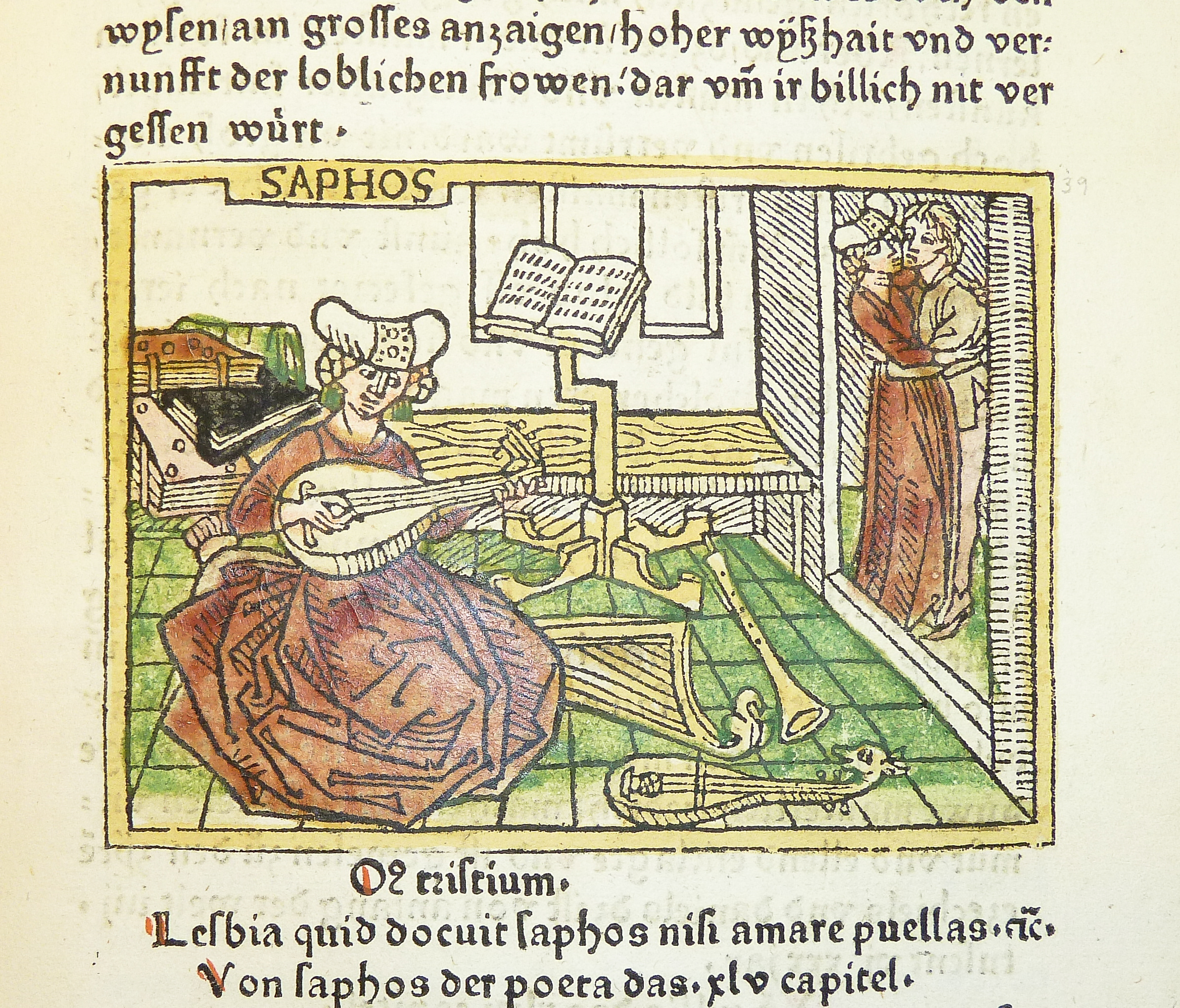

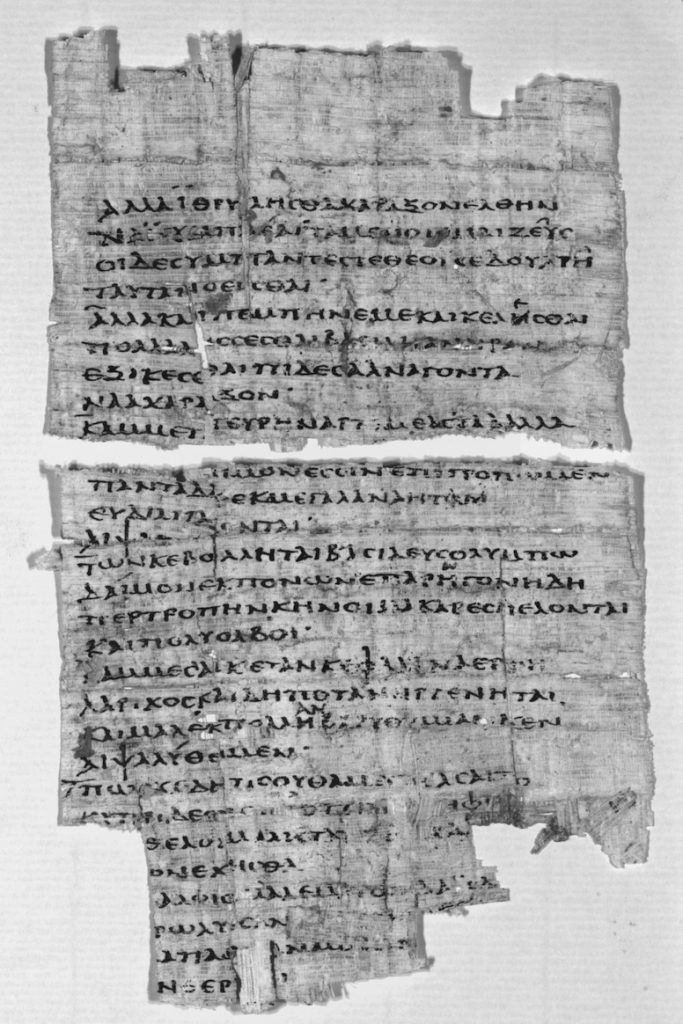

510 BCE Sappho on pottery (left), 1474 Woodcut Illustration of Sappho (center), 100 CW fragment of Sappho;’s poetry (right) CC

Sappho was known as the Tenth muse by the Greeks and in our age as the “seventh-century lyric genius.” It is believed that Sappho was an educator of young girls from the elite classes. Her poems were recited publicly, including at weddings. Sappho’s poetics stand at the beginnings of Western lyrical poetry and her poems are personal, emotionally heartfelt, and poignant in style. Sappho’s poetry comes to us in concise poetic lines by fragments reflecting human sensibilities known to the Greeks as Eros and Aphrodite, the God of Love and Goddess of Beauty, respectively. Sappho created the four-line stanza and the Sapphic stanza, which has three lines of eleven syllables and a short fourth line of five syllables which serves as a refrain, a repeated idea. Discoveries of Sappho’s poetry continue into the twenty-first century. In 2014 two poems of her style and attribution were found on papyrus dating back to 200 AD.

Key Points

- Featured are early origins of lyrical poetry

- Addressed fragments of Sappho

- Highlighted lyrical poetry and classical allusions and symbolism

- Focused UNSDG, like on inequality, peace and justice, and gender equality

Media Attributions

- Sculpture of the poet Sappho of Lesbos © Wikipedia is licensed under a Public Domain license

- Toussaint L’Ouverture © Wikipedia is licensed under a Public Domain license

- Woman and slave © Wikipedia is licensed under a Public Domain license

- Sojourner Truth © Wikipedia is licensed under a Public Domain license

- Tallahatchie River © Wikipedia

- display-inside-the-emmett-till-historic-intrepid-center-in-an-old-cotton-gin-a4027f-1024 © PICRYL is licensed under a Public Domain license

- Brooks and Knight © PennSound is licensed under a CC0 (Creative Commons Zero) license

- Sappho on pottery © Wikipedia is licensed under a CC0 (Creative Commons Zero) license

- Poem of Sappho © Wikipedia is licensed under a Public Domain license

An epic originates from oral tradition, in contrast to the literary epic, and many are written in poetry. With an overarching narrative of several tales woven together, the topics and themes of an epic range from the origins of the cosmos, emergence of life and humanity, and heroes’ journey toward order. Epics were originally sung and performed annually, or a chosen part at a specific season. They relate narratives about people’s geographic sense of home via its plot and characters. Epics may also relate the founding of civilizations and empires. We have many of these epics today because they were eventually written down, like India’s Ramayana and the Mahabharata written in Sanskrit, Spain’s first written epic is El Cid (1100 AC) written in old Spanish, England’s is Beowulf (1000 AC) written in Old English, and France’s is Song of Roland (1000 AD) written in old French, while the Maya Popol Vuh comes in written hieroglyph storyboards and the epic of Sundiata is still orally performed every year in North Africa. Well-known epics include those by Native Americans — the Haudenosaunee Confederation, the Cherokee, the Sumerian’s The Epic of Gilgamesh, Greek’s The Iliad, English Beowulf, N. Africa Sundiata, and the Mayans Popol Vuh. The Creation by the Haudenosaunee (People Who Build A House), a confederation of Indigenous communities included the Mohawk, Oneida, Onondaga, Cayuga, and Seneca, whose territory covered a vast region from the eastern part of North American (what today is known as eastern New England seaboard) to Ohio and northward at Canada’s Lake Ontario.

Indigenous communities is a proper noun that refers to the peoples who have lived throughout North America for over 10,000 years, where they historically call Turtle Island. This territory reaches beyond the borders of today’s Canada and the United States. Hence, Indigenous communities are the “descendants of those who survived the colonizing apocalypse that started in 1492 and continues today” (Justice 2018). They affirm their “the spiritual, political, territorial, linguistic, and cultural distinctions” throughout numerous and varied tribes. Indigenous communities experience stories and their ancestral lands as crucial to the survival of their culture and heritages. They learn and share the world by storytelling, including oral traditions on science, medicinal biological knowledge, and religious rituals. The capitalization of the word Indigenous “affirms a distinctive political status of peoplehood” with agency (Justice 6).

Aeolian verse is form of poetry attributed to Sappho. An Aeolian poem has a meter of two anceps (a long or short syllable) and the same metric form (fixed syllables) of an ionic four-syllable foot (unaccent, unaccent, accent, accent). Visit Key Terms for more information.

A Greek poet as significant as Homer on the legacy of Greek mythology. He wrote the first known Farmer’s Almanac with wise sayings that Benjamin Franklin emulates in his work. Hesiod wrote poetry, on agriculture, early Greek astronomy, and economic theory. Like the Sumerian poet Enheduanna, he is the first known Greek poet who viewed his work as ‘an individual’.

The Gaia hypothesis is also known as the Gaia principle and Gaia Theory. The Gaia hypothesis realizes the life-giving forces of life on Earth, which dictate a worldview that is more ecologically sound and grounded like Indigenous thought. The concept that “Earth is a single organism” was popularized and accepted by modern scientists in the 1970s (Abou-Agag 2016) when British chemist James E. Lovelock and U.S. biologist Lynn Margulis coined the “Gaia Hypothesis” after the Greek Earth goddess (Britannica). They proved the importance of conceiving of things as a whole in science, a similar perspective known to Indigenous people like the Lakota, which Vine Deloria Jr. and Daniel Wildcat explain in Power and Place: Indian Education in America (2001). This principle is addressed by Deloria and Wildcat in their explanation of Indigenous metaphysics. Lakota philosophy also overlaps with recent understandings of the Gaia hypothesis. Again the ‘interconnectedness’ of the planet to sustain life is a worldview shared by many cultures, including the Lakota of the American plains region (Deloria). “With the entire Earth unified in this way, it seems artificial to distinguish between the parts that are obviously alive (the biota) and the inanimate oceans, rocks, and clouds. These inanimate parts are tightly coupled in chemical processes with the biota”(Abou-Agag 2016). In the 1970s Microbiologist Lynn Margulis and Chemist James Lovelock continues Goldsmith’s work on the Gaia hypothesis, as those who formulated this hypothesis and who “introduced into it the further complexity of the chemical reactions between the atmosphere and rock surfaces as they weathered (a process that bacteria can accelerate) and also the oceans full of algae.” The result was a chemical model of a complex interconnected chain of reactions whose ultimate effect was to regulate the conditions on Earth for the benefit of its life forms. “As Edward Goldsmith writes in The Way: An Ecological World-View, ‘What is required is a totally non-mechanistic theory of life and such a theory must by its very nature be holistic. Living things are alive because they are part of a whole.’ The main features of living things, those that make them alive – their dynamism, creativity, intelligence, purposiveness – are not apparent if one studies them in isolation from the hierarchy of natural systems of which they are a part" (qtd. in Sandner 2000).This model he called Gaia (Abou-Agag). For more information, visit OER Pressbooks on Classical Mythology & OER On Gaia by Harvard Edu.

The concept of nature is a social construct with qualifiers that make nature idyllic, or ‘balanced.’ Yet, in non-Western literary traditions, references to nature reflect real lived experiences, immersed in nature. For example, in Indigenous oral traditions, nature is dynamic. Adamson explains, “They tell of wars, crisis, and famine…they learned to live with ambiguities, to see the patterns, and to mimic natural processes in the cultivation of their gardens” (Adamson 56). Ecocritics and environmental humanists, among other scholars, witness humans as also a social construct in opposition to nature, or the nonhuman, which is witnessed throughout literature. Instances of the feminization of nature are understood as gendered ethnocentric views of nature by those who define humanity as superior to nature, and the masculine gender as superior to the female gender. These social constructions suggest anxieties about what it means to be human and overlap with discourses on power and colonialism when the colonized are effeminate, along with the conquered landscape. The gendering of a people and nature acts as a mechanism that initiated modernity, inequalities ecofeminist Soper addresses, “given the widely perceived parallels between the oppression of women and the destruction of nature” (Soper 1995). Feminist philosopher Kate Soper also argues on how nature is an ‘otherness’ in What is Nature: Culture, Politics, and the Non-Human (1995) to focus on Western attitudes from two schools of thought, on ecology and cultural criticism - that of our current climate crisis and efforts to address this crisis while understanding “the politics of the idea of nature,” on the semiotics of ‘nature’. Intersections between perception of nature and theories of sexuality offer insights into ‘the politics of the idea of nature.’

Was coined by Hamilton and in 1967, Black Power. In the preface of Black Power Ture and Hamilton outline the purpose of their project for Black independence liberated from oppressed by a system that repeatedly has proven to subjugate and co-opt Black achievements only to reward individual efforts to remain docile and maintain the status quo. Black Power offers ways to liberate the people of Africa and Pan-Africanism that include Black consciousness. Their method is well-thought out, “In order to find effective solutions, one must formulate the problem correctly. One must start from premises rooted in truth and reality rather than myth” (Preface xvi). OER on Institutional Racism

According to ecocritic Lawrence Buell’s definition of ecocriticism, which involves the philosophical view that “human being and human consciousness are thought to be grounded in intimate interdependence with the nonhuman living world,” this “interdependence” is the web of life (Buell 2011). According to Danel Wildcat and Dine Deloria Jr. – whose son is currently History faculty at Harvard Dr. Philip Deloria (wiki on Philip Deloria), the worldview, the metaphysics of Indigenous peoples in North America experience reality as ‘related,’ the world is unified, and all aspects have significance and share a commonality among the tangible, spiritual, intelligent, and intangible. “The teachings of the tribe are almost always more complete, but they are oriented toward a far greater understanding of reality than is scientific knowledge”(OER Pressbooks on Indigenous Education, go to Ch. 9). As a more thorough and intuitive philosophy, they expose the limitations and exclusionary culture of Western culture and its reliance on Cartesian dualistic philosophy: “We live in an industrial, technological world in which a knowledge of science is often the key to employment, and in many cases is essential to understanding how the larger society views and uses the natural world, including, unfortunately, people and animals.”

White Supremacy in Literary Studies operates thematically, ideologically, by school of thought or critical theory, and on intersections involving legal theory. Instances in a piece of literature that define humanity in terms of superior and inferior are identified to understand its trends and influences. Visit Key Terms for more information.

(“eco” in Greek is household, ecology is the learning of the life of populations)

What is ecocriticism? At first sight, it is simply a literary theory to learn about nature in literature; when critics approach literature to learn about nature, they are offering ‘ecocritical’ interpretations. Ecocriticism aims to not reduce nature into a concept or social construct, which the Western tradition shows in the majority of its literary traditions. Literary studies offers a platform to learn about representations of nature in texts, while analyzing themes on social injustices, which may share similar treatments, since “ecocriticism is a theory that seeks to relate literary works to the natural environment” (Estok 2005). Another explanation is “the study of the relationship between literature and the physical environment” and “takes an earth-centered approach to literary studies” (Glotfelty and Fromm 1996). Another explains that, “Ecocriticism examines the representation of and relationships between the biophysical environment and texts, predominantly through ecological theory” (Chisty 2021). Since the 2000s, ecocriticism has relied on scientific and philosophical approaches to understand humanity’s place in the world. The UNSDG offer a wide-ranging view of aspects of human’s roles to address current injustices and the climate crisis. Partly, it is “committed to effecting change by analyzing the function – thematic, artistic, social, historical, ideological, theoretical, or otherwise – of the natural environment.” Ecocritical readings on environmental injustices can intersect with social injustices, like Langston Hughes’ poem expresses. *Go to the section on Langston Hughes’ poem A Dream Deferred in the introduction of this book. This class supports intersections between social injustices and environmental ones. The work of Joni Adamson, American Indian Literature, Environmental Justice, and Ecocriticism: The Middle Place (2001) features the literatures of Indigenous communities and literary analyses with ecocritical understandings to address and expose Western abuse of nature and the causes of our current environmental crises, while demonstrating the literary and storytelling traditions of Indigenous communities as ‘an alternative’ theory. For more information, visit OER on Ecocriticism. This literary theory stems from the first wave of environmentalism in the U.S. by ecofeminism. The term ecocriticism emerged in the article Literature and Ecology (1978) by William Rueckert and an earlier work in 1972 by William Meeker The Comedy of Survival: Studies in Literary Ecology. “First wave" environmental criticism concerns itself with conventional nature writing and conservation-oriented environmentalism, which traces its origins to the work of Ralph Waldo Emerson, Henry David Thoreau, and John Muir. "Second wave" environmental criticism redefines the environment in terms of the seventeen Principles of Environmental Justice and increasingly concerns itself with "issues of environmental welfare and equity" and "critique of the demographic homogeneity of traditional environmental movements and academic environmental studies” (17 Principles of Environmental Justice). A modern third wave of ecocriticism recognizes ethnic and national particularities and yet transcends ethnic and national boundaries; this third wave explores all facets of human experience from an environmental viewpoint” (Adamson 2009). Originally, ecocritics looked at the relationship between literature and nature – between culture and the global environment. Literature shows human tendencies to anthropomorphize nature. Ecocritics see culture as hierarchical and in contrast to nature, especially in Western texts. To analyze this relationship, nature needs to be distinct from human constructs: the wilderness, scenic sublime, countryside, and domestic picturesque. Man-made factors are social orders and political constructs like culture and poverty. Yet, the ‘setting’ of narratives may also be fantastic – as in folklore, the gothic, and science fiction, and hence is also fertile soil for ecocritical readings. Ecocriticism takes as its subject the interconnections between nature and culture, specifically the cultural artifacts of language and literature. As a critical stance, “it has one foot in literature and the other on land; as a theoretical discourse, it negotiates between the human and the nonhuman" (Glotfelty and Fromm qtd. in Sandner 2000). The roots of the environmental movement can be traced back to the abolition movement, which revealed the connections between colonization, conquest, slavery, resource exploitation, and capital, and many of the most successful strategies of early environmentalism were borrowed from the abolition, civil rights, and women's movements and American Indian Land Claims lawsuits. For this reason, “any history of environmentalism that did not include W. E. B. Du Bois, Rosa Parks, Martin Luther King, Jr., or Cesar Chavez, among others, would need to be revised” (Adamson 2009).

A symbol is an object, expression or event that represents an idea beyond itself. The weather and light/darkness will often have a symbolic meaning. Survey of Native American Literature: Symbols in Literature