Chapter Five: On Mythology As Adaptation and Gender & Justice Intersections

Outcomes and Skills Practiced

- Chapter Five builds on your familiarity with folklore in the adaptations of classical mythology

- To succeed in this chapter, select several assignments to practice close reading skills and textual analysis of mythology as adaptation and ecocritical approaches to literary studies

Let’s tell stories for a while, if you please, but let’s make them relevant,

as Horace says. For stories…are not only the first beginnings of philosophy.

Stories are also—and just as often—philosophy’s instrument.

Poliziano, Lamia 1492

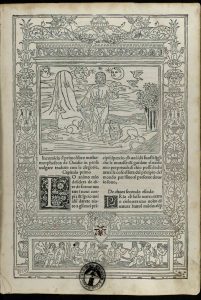

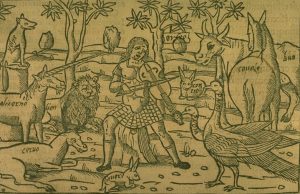

1497 edition of Ovid’s Metamorphoses, 1505 of Orpheus in Book X, & 1606 Plate from Book 1 on “The Creation” by Ovid CC

The previous section addresses mythology in early oral traditions and the epic from cultures across geographic regions to address intersectionality on current sustainability challenges. These engagements in textual analysis with the literature of Sumerian, Mayan, North American Indigenous and West African Mali traditions demonstrate literary studies approaches that disclose the relevance of ancient texts for twenty-first century learners. The section concludes with ecocritics. They explain how various ancient storytelling traditions faced challenges with the environment and natural resources. While some traditions attempted to ensure sustainable relationships with nature, other collaborations were antagonistic, very much like modern-day human-nature disparities.

Literary tropes are also identified in ancient origin myths. They explain the physical world and unknown experiences through archetypes, like the mother and father, creator and destroyer, light and darkness, and the sky and the underworld. In folklore other archetypes emerge in fables and animal tales, like tricksters, villains, fools, and characters who lack experience.

How is Classical Folklore Retold in Later Works as Adaptations?

A common practice among storytelling around the world is to share and retell stories. Retold variations of stories are adaptations. Retellings of mythological figures whereby similar characters reappear throughout different epochs and cultures are considered archetypes. These are characters who represent inherent qualities that all people hold.

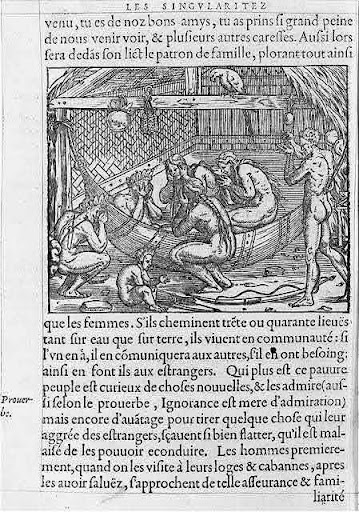

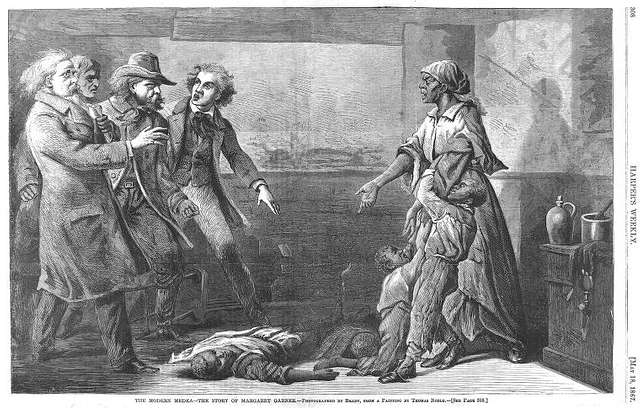

1860s Cupid & Psyche (left), 1559 Indigenous weeping women, 1867 Illustration of Margaret Garner, & Mexico’s La Llorona CC

An ancient prototype, the figure of Niobe in Greek mythology emerges as an archetype in retellings of mothers who lose their children by forces beyond their reach. Modern variations of the Niobe archetype are witnessed today in the Weeping Woman legend. She is a female figure in folklore known throughout Southwestern, Chicano, Mexican, Caribbean, and Central American storytelling traditions by the name of La Llorona.

The Niobe archetype should not be confused with the Medea archetype. Known throughout modern literary works like Toni Morrison’s Beloved, this female figure, unlike Niobe, defies patriarchal gender designations and victimhood identifications. She represents “a strong-willed and desperate woman driven to unthinkable acts of violence” (Marks 2013). Since Euripides’ Medea (431 B.C.E.), this figure takes matters into her own hands to represent transformative agency.

How does Adaptation Transform in Theater, the Novel, Film, & Television?

We witness adaptations of previous works in novels, short stories, comics, and graphic novels. Yet adaptations have also transformed classical theater and even ancient religious scripture. Euripides’ Medea (431 BC) and Sophocles’ Oedipus Rex (429 BC) are themselves adaptations of oral tradition. These dramatic works adapt Greek mythology from ancient religious cults. Through retellings, adaptations that may have originated in an oral tradition are now shared in mass media through film, broadcast radio and television, as well as by online streamed series.

It is important to note that the dramatic performances of the ancient Greek theater were part of the annual religious and civic celebration known as the City Dionysia, an annual festival in Athens, commemorating Dionysus, the god of wine, fertility, and ritual madness. The theatrical performances were the central focus of the festival and included two major types of drama: tragedy and comedy (also known as satyr plays). (Pressbooks on Greek Theater)

The printing press in the sixteenth century and the emergence of cinema in the late nineteenth century are modern technologies that opened new doors for storytelling and adaptations, especially from the novel to film.

Bram Stoker’s Dracula and Arthur Conan Doyle’s Sherlock Holmes novels have been adapted in a range of national contexts but probably the most adapted author is Shakespeare, whose plays have appeared in film form as a large-budget Hollywood musical (West Side Story (Jerome Robbins and Robert Wise, US, 1961)), a historical epic set in feudal Japan (Kumonosu-jo/Throne of Blood (Akira Kurosawa, Japan, 1957)…to name a few. Pressbooks on the Adaptation

The current online streaming culture is a result of new services through online platforms whose storytelling has depended on previous platforms and technologies – in print, celluloid and radio and television.

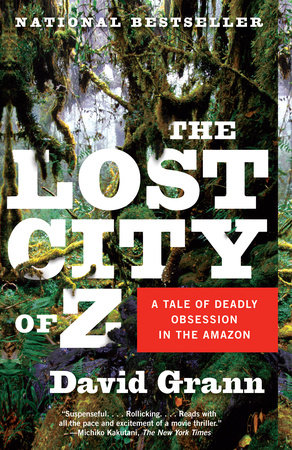

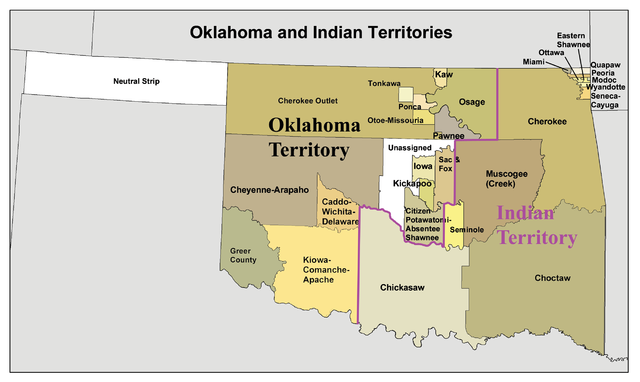

2018 Tablet Streaming, Print media of Grann’s book, Book adapted in 2023 Film on Osage Nation in Oklahoma (1890s map)

By the late twentieth century, online technologies began to converge on the internet. This virtual technology has enhanced the sharing of information and communication through several platforms and search engines to facilitate the online streaming culture of storytelling we know today (Pressbooks on the Internet).

While Internet distribution gained some traction during the 2000s, web series were hardly mentioned in the same breath as traditionally televised programs, lacking the cultural legitimacy to be taken seriously as a form of televisual storytelling. Nonetheless, the experimentation with distribution and release strategy during this period set the stage for the streaming services of today. Sharma 2016

Modern storytelling technologies are part of our daily lives. We carry films and stream shows through our cell phones, tablets, and computers. With today’s streaming culture, adaptations are part of the norm in television, film, and streaming series.

Critics trace these modern adaptations at the advent of the silent film and throughout today’s streaming series – like the adaptation of the novel The Color Purple (1982) by Alice Walker into a film in 1985 by director Steven Spielberg and into a musical version in 2004 by Quincy Jones, Emma Thompson’s 1995 cinematic adaptation of Jane Austen’s novel Sense and Sensibility (1811), and a recent comedy horror cinematic version Pride and Prejudice and Zombies (2016) directed by Burr Gore Steers that is based on a 2009 adaptation of Austen’s novel by American writer and film producer Seth Grahame-Smith.

Current streaming services also offer adaptations of novels into a series, like American playwright Branden Jacobs-Jenkins’ 2016 television series adapted from American science-fiction writer Octavia Butler’s novel Kindred (1979) and 2017 television series by Bruce Miller of Margaret Atwood’s 1985 dystopian novel titled The Handmaid’s Tale.

What is Ideology Relativity in Adaptations?

When we work with two versions of the same story, an early version and a current adaptation, we are challenged with the analytical task to accurately identify how a story has been adapted in regards to ideology. For example, we can read the comics Superman and The Black Panther and learn about how heroism and villainy are represented at the time of their publications. But, when we review current adaptations of the same stories, its ideals and values of heroism and villainy have changed, perhaps due to a need to address the current generation and or to appease the whims of those who directed and produced the adapted versions. These variations of social norms and values witnessed in an adaptation are examples of ideology relativity.

On Ecocriticism and the Adaptation in Mythology & Abolitionism

Ovid’s revision of the Niobe myth in The Metamorphosis enhances her agency as a figure who experiences injustice and powerlessly suffers. The poet Christine de Pizan in the High Middle Ages also revisited the Niobe mythological figure in her own work to confront her contemporary misogynistic romances that negatively misrepresent women. The lyrical poetry of modern poets also demonstrates reimaginings of mythology on the figure of Niobe.

Pioneering Black poet Phillis Wheatley, who was captured from Africa and then sold into slavery in the United States, rewrote the classical prototype of the ‘weeping mother’ to respond to Ovid’s Niobe and to reposition the tradition of Western lyrical poetry within an abolitionist context. Through her reimagined adaptation, Wheatley’s poetry unveils the lived experiences of those who suffered bondage under American slavery.

Activity

For example, in her poem Niobe in Distress for Her Children Slain by Apollo, from Ovid’s Metamorphoses, Book VI. And From a View of a Painting of Mr. Richard Wilson, Wheatley uplifts the plight of the trauma enslaved mothers undergo through classical myth:

The queen of all her family bereft

Without or husband, son, or daughter left

Grew stupid at the shock…

A marble statue now the queen appears,

But from the marble steal the silent tears.

Wheatley’s rewriting of Ovid’s Niobe from Book VI of The Metamorphoses transforms classical poetry into abolitionist lyrical poetry through ideology relativity. This treatment of Niobe places the mother figure at the center of the myth. Ovid’s version of the myth does not center Niobe on her experiences. Hence, Wheatley’s poem is not only a depiction of the trope of the weeping woman, but her adaptation also alludes to the current lived experiences of those who have been enslaved, a reimagining that is also fruitful for ecocriticism on abolition literature.

An engagement with African American experiences in the United States is necessarily an environmental one, whether, for example, in the transatlantic crossing, plantation labor, or the Great Migration, although critics often do not bring an ecocritical lens to such historical events (Wardi 2021).

Classical themes in abolitionist lyrical poetry challenge us to study literary works of previous epochs, like those by Ovid and more recent works. Let’s proceed in literary studies to witness ecocritical earlier works.

How Does Ovid Approach Adaptations of Greek Myth?

Roman poet Ovid – known by the noble name Pubublius Ovidius Naso – lived at a time of peace in Rome. In 44 B.C. chaos and disorder ensued when the Roman Republic collapsed during its civil war after Julius Caesar was assassinated (Ovid, Metamorphoses, A Norton Critical Edition 2010). After much political tumult, Emperor Augustus restored order during his reign from 31 B.C. to 14 C.E.

Orpheus in 300 B.C. (left), Statue of Apollo (center-left), Temple of Apollo (center-right), & 1700s Emperor Augustus (right) CC

Unlike Roman epic poet Virgil who witnessed the fall of the republic, by the time Ovid wrote his poetry Roman culture and society was reinvented by Augustus. Roman iconic and emblematic traditions, including its ancient poetic symbols – the ‘laurel’ in particular – were redefined by Augusts to celebrate the Roman military and its imperial values.

“Under the Augustan Principate, the ancient symbols of the laurel tree, along with the symbolism of oak, were absorbed into the iconography of the emperor himself” (496).

In The Metamorphoses and his other works, including his epistolary personal works, Ovid challenged established Augustan ideology. For example Ovid’s rendition of Dido’s mistreatment by Aeneas, an account Virgil elaborates on in Book 2 of the Aeneid, a literary epic on the founding of Rome, demonstrates the hero’s deceit and malice, which leads to Dido’s suicide in Virgil’s epic. Ovid gives voice to Dido to implicate Aeneas’ abuse towards her, and in turn to expose immoral classical misogyny.

“You deceived me in all; nor am I the first credulous fool deluded by that perjured tongue, or the first who have suffered from a rash belief” (OER Ovid’s Letters, Epistolary works).

Ovid addresses pre-Augustan Roman emblems in Fasti, a long narrative literary poem with a narrator who engages in interviewing Greek deities, as allegory with satirical overtones. Resembling an investigative journalistic text, its narrator alludes to Roman traditions that honored poets and iconic emblems like the laurel wreath.

“The laurels that are theirs and that adorn the pained calendar, thou too shalt win in company with thy brother Drusus. Let others sing of Caesar’s wars” (OER English Translation of Fasti, Gutenberg).

Ovid continues to elaborate on Augustus’ cultural revolution throughout the poem Fasti.

In the olden times the gifts were coppers, but now gold gives a better omen, and the old-fashioned coin has been vanquished and made way for the new. We, too, are tickled by golden temples, though we approve of the ancient ones: such majesty befits a gold. We praise the past, but use the present years; wed are both customs worthy to be kept. (Lines 189-227).

How does the Metamorphoses Reflect Adaptations of Mythology?

In light of Ovid’s use of verse to critique contemporary political events surrounding Augustan rule, his masterpiece – The Metamorphoses – may also be read and understood as allegory with satirical overtones. Modern readers can appreciate Ovid’s reimaginings of classical mythology and his stories as adaptations. Ovid’s version serves to renew and reinstate social cohesion.

Written when Ovid was exiled, The Metamorphoses is a narrative poem that blends elements of epic and lyrical poetry in twenty-five books. But, unlike Virgil’s literary epic The Aeneid that celebrates the Roman Emperor Augustus and emulates his values of order and stability, Ovid’s work offers dozens of mythological stories linked by the overall theme of transformation and chaos.

The theme of transformation serves both to present a philosophy of constant change in a chaotic physical world that is never static and to contrast Augustan ideology, of its values of social order and permanence. Ovid accomplished his theme throughout The Metamorphoses with his refashioned retellings of Greek mythology with characterization and plot development not seen in the works of Hesiod and Homer. Ovid challenged Augustan notions of order and stability, through representations of nature and female deities.

Activity

Ovid also establishes the ancient philosophy of the creation in The Metamorphoses, to highlight the Great Chain of Being.

“According to them, God was not the Creator, but the Architect of the universe, in ranging and disposing of the elements in situations most suitable to their respective qualities. This is the Chaos so often sung of by the poets, and which Hesiod was the first to mention” (Ovid, Metamorphoses, A Norton Critical Edition 2010).

Known for going against established social and political norms of Augustan virtues, Ovid’s refashioning of Greek myth highlights the temporality and ever-changing dynamics of life. The stories themselves emulate the same superstructure – reality and nature as dynamic and ever changing, but they also reclaim traditional symbols.

The mythological story “Daphne and Apollo” in Book I is one example where Ovid reclaims the laurel, an ancient tradition of wreath that was “associated with the god of poetry, and thus poetry itself” (Norton 495).

…my quiver shall always have thee, oh laurel! Thou shalt be presented to the Latian chieftains, when the joyous voice of the soldiers shall sing the song of triumph. OER On Ovid and Metamorphosis

How do the Works of Ovid Address Elements of Ecopoetics?

An ecocritical reading of Ovid’s work contributes to literary studies on folklore at a period of Roman history when tensions between peacemaking efforts and the will to consolidate power challenged poets and the populace alike. For example, an ecocritical reading of the works of Ovid offers new insights on his work and on topics important to literary studies on nature and its mistreatment.

Topics relevant to twenty-first century sustainable goals from the works of Ovid like those outlined by the United Nations (UNSDG) include: life on land and below water, gender equality, reducing inequality, sustainable communities and cities, quality education and peace and justice.

Key Points

- Adaptations of mythology blur lyrical poetry with the narrative

- Mythology in abolitionist and Roman poetry can challenge popular ideology

- Retellings of mythological stories appear in Abolitionist and Chicano poetry and legends

- Literary tropes and archetypes emerge in retellings of mythological figures

- Ideology relativity in adaptations inform on cultural norms and unveil themes on social justice

- Ecocriticism enhances analysis of poetry on adaptations of mythology

Media Attributions

- 1497 edition of Ovid’s Metamorphoses © Wikipedia is licensed under a Public Domain license

- 1505 of Orpheus in Book © Wikipedia is licensed under a Public Domain license

- “The Creation” by Ovid © Wikipedia is licensed under a Public Domain license

- 1559 Indigenous weeping women © getarchive logo is licensed under a Public Domain license

- the-modern-medea-the-story-of-margaret-garner-10531a © getarchive logo is licensed under a Public Domain license

- lost city z © Penguin Random House is licensed under a All Rights Reserved license

- Killers of the Flower Moon Poster © Wikipedia is licensed under a All Rights Reserved license

- Flag of the Osage Nation © Wikipedia is licensed under a Public Domain license

- 1890s map of the Osage Nation in Oklahoma © Wikipedia is licensed under a Public Domain license

- Statue of Apollan Warrior © Wikipedia is licensed under a Public Domain license

- Lotte Reingers 1926 © Lotte Reingers is licensed under a Public Domain license

- Augustus Emperor of Rome © Look and Learn is licensed under a CC0 (Creative Commons Zero) license

This phrase in academic circles, especially in the Humanities is a broad way of engaging with a text – in anthropology, communication, history, literature, philosophy, political science – for the purpose of concretely understanding both its content and role in a particular discipline and school of thought. For a more detailed understanding of textual analysis go to OER Intro. to Humanities Book.

The fable is one example of a literary form of folklore, like the animal fable. The fable is witnessed in Aesop’s Fables from 600 B.C.E and other examples include those from India and the Middle East. Fables and the animal fable in particular can help us to conduct ‘ecocritical’ readings. Like the fairy tales and Arabian Nights, readers may experience and explore the non-human in the fable.

In Shakespeare’s drama, “Characterization is the fundamental and lasting element in the greatness of any dramatic work.” Characterization is the exhibition of passions, motives, feelings in their growth, engagements and conflicts. Dialogue becomes an essential adjunct to action. The principal function of dialogue is characterization.” Also, “Soliloquy and asides are dramatist's means of taking us down into the hidden recesses of a person's nature, and of revealing those springs of conduct which ordinary dialogue provides him with no adequate opportunity to disclose.”

In literary criticism, critics analyze the actions of key characters, and one purpose in doing so is to explain whether certain characters are ‘active’ in the plot itself, through choices and independent action – this is agency. Shakespeare’s Isabella in Measure for Measure and Shahrazad in One Thousand and One Nights are examples of characters whose agency drives the narrative.

When a current director, playwright, poet, or novelist reworks a piece of literature, this is adaptation. Adaptations are acts of ‘narrative’ renewal to reinstate ‘social cohesion.’ A film adaptation is a cinematic adaptation of a work of literature, like the 2013 film The Great Gatsby that adapts Francis Scott Fitzgerald’s 1925 novel. Several texts by Neil Gaiman and Stephanie Meyer’s Twilight novel series are examples of works of literature that have been adapted into films. Well-known film adaptations are Robert Mulligan’s 1962 version of Harper Lee’s To Kill a Mockingbird (1960), Steven Speilberg’s 1993 version of Thomas Keneally’s Schindler’s List (1982), Ang Lee’s 2015 film Brokeback Mountain, adapted a 2001 short story by Annie Proulx, and The BlacKkKlansman by Spike Lee adapts the 2014 memoir by Ron Stallworth. Filmmakers Alred Hitchcock, Jane Campion, Martin Scorsese, Francis Coppola, and among many others have adapted prior works as film adaptations. Other forms of adaptations are from story and novel to radio productions, like Orson Welles’ 1938 radio drama War of the Worlds. Audio books and podcasts are also considered adaptations. In art and literary studies, adaptation occurs when a text "signals a relationship with an informing source-text or original." Scripture, mythology, the work of Ovid, Christine de Pizan, and William Shakespeare also adapt previous works and source-texts. Methods of adaptation include: transposition, commentary, analogue” (OER). Do not confuse an adaptation with a film remake. A cinematic remake is a remake of an old film, such as the remake of 1974 The Stepford Wives in 2004 by director Frank Oz. The 1974 film is an adaptation of the 1972 satirical novel at the advent of feminist horror by Ira Levin. He also authored other novels like Rosemary’s Baby (1967).

The printing press was invented by Gutenberg in the 1460s. Visit Key Terms for more details.

A comedy in a book, play, story, or film engages audiences through expressions of trickery, wit, paradoxes, and even satire. One example is a well-known technique throughout William Shakespeare’s plays – mistaken identities and misunderstandings.

Octavia Butler is a seminal Afrofuturistic author whose works of science-fiction intersect with themes involving African diaspora and their heritages. Visit Key Terms for more details.

“A more or less systematic ordering of ideas with associated doctrines, attitudes, beliefs, and symbols that together form a more or less coherent philosophy or Weltanschauung for a person, group, or sociopolitical movement” (APA Dictionary qtd. BU Equity Guide). In schools of thought such as political science and psychology, ideology is addressed as a system of beliefs that underpins and sustains the form of a society. A school may be supported by an ideology of curricular vigor that rewards certain achievers. The economy of a country may be supported by a capitalist ideology. But, ideology is also understood through other worldviews and cultural norms, like those practiced by the Indigenous communities of the Americas.

Ovid, known during his lifetime as Publius Ovidius Naso, was a Roman poet who completed the epic poem the Metamorphoses by 8 C.E. This is a masterpiece of fifteen books in Homeric heroic verse on Greek and Roman mythology. Its content contextualizes the era of Emperor Augustus and is placed within the tradition of the epic that Virgil helped to revive through the Aeneid (29 B.C.E. to 19 B.C.E.). The Metamorphoses weaves in over 200 mythological stories to emphasize the theme of chaos over order, which is initially established in Ovid’s version of cosmogony, the creation, at the opening of his epic. Classicist literary scholars recognize Ovid’s theme as a response to Augustan virtues and rule (OER Article on 'sins' of Romans). Other works by Ovid include a satire on romantic love and an epistolary collection of female goddesses addressing their male counterparts. For more information, visit On Ovid, from Tufts University).

Christine de Pizan is of French descent who lived during the high middle ages when humanism sparked intellectual circles across Europe – a revival and rebirth of classical rhetoric, history, and literature. She is Europe’s first author who lived on the earnings of published work.

Misogyny is a cultural sentiment and social norm witnessed in Western cultures whereby social constructions of the feminine reflect treating anything associated with the female as inherently inferior and with a degree of hostility that culminates toward ‘hatred’ and even justified violence. The work of Christine de Pizan and scholarship on global rape culture through movements like #MeToo investigate misogyny. Contemporary studies on misogyny also offer a methodology to support present victims, to demystify victimhood, and to empower women as rape prevention by “discourses of survival“ (Torres, McNamara qtd. Holland, Hewett 328).

Phillis Wheately is from the region known today as Senegal. Wheatley survived the ‘middle passage’ and in 1761 was sold into slavery in Boston, Massachusetts. She was named after the ship that transported people, including Phillis, at approximately the age of eight years old. Visit Key Terms for more details.

How and when information is presented. For example, to understand a historical fact – like African slavery in the Americans – it is important to know its context. Context means any background information that contributes to African slavery in the Americas. The context can address 1526 when the Spanish took Africans to Georgia and S. Carolina, or 1619 when the English brought African slaves, or even 1440, when the Portuguese first brought Africans to Europe. Hence to understand African slavery in the Americas we should research its context. This also includes the 800-year history of the African Moors in Europe. Starting in 711 C.E.

Abolition literature is “transformative literature” (Acheson 2022) on revolutionary thought informed by the struggle for liberation, independence, and self-actualization (Angela Davis 2022). Visit Key Terms for more details.