Chapter Four: Greek and Roman Folklore: How Do Fables Intersect with Sustainability Goals Life on Land and Quality Education?

…traditional stories and folktales from specific places and particular communities are not an occasion for discourse among critics but …necessary nourishment for their people and one way by which they come to understand their lives…

Barbara Christian

Three depictions of Aesop’s Fables – from Spain (left), Greece (center), & Japan (right). CC

Introduction of Chapter Four

Outcomes and Skills Practiced

- Chapter Four presents critical approaches to close read and identify aspects of the fable featured in Aesop’s Fables

- To succeed, select several assignments to continue to practice textual analysis on the fable with ‘ecocritical’ approaches

Dr. Martin Puchner reminds readers that literary studies also treats literature as a cultural phenomenon that has ties to sharing folklore across regions and continents, through historical trade routes. The fable, for instance, is part of a collective matrix of multicultural legacies of stories that were collected and compiled. These collective compilations existed longer than the first known libraries in 600 B.C.E and may compete with the oldest known cuneiforms from 2100 B.C.E. of the Epic of Gilgamesh, which were housed at the library of Ashurbanipal, Syria in 600 B.C.E. In his 2023 book titled Culture: The Story of Us, from Cave Art to K-Pop, Puchner describes the culture of collecting and compiling ancient folklore.

This view is exemplified by Zuangang, the Chinese traveler who went to India and brought back Buddhist manuscripts. It was embraced by Arab and Persian scholars who translated Greek philosophy. It was practiced by countless scribes, teachers, and artists who found inspiration far outside their local culture. In our time, it has been endorsed by Wole Soyinka and many other artists working in the aftermath of European colonialism. Culture, for these figures, is made not only from the resources of one community but also from encounters with other cultures. It is forged not only from the lived experience of individuals but also from borrowed forms and ideas that help individuals understand and articulate their experience in new ways. (Puchner xi-xii)

His description also shows a different understanding of literature. We can understand literature as also representing a collective cultural phenomenon, one that many of our own peoples around the world since ancient times and for several millennia have participated in and have contributed to as compilers, collectors, and or at times as adaptors of older stories into renewed versions. The literature we have available to us today is the result of their efforts as ambassadors of culture. They played a key role and did their part to share and perform, to write and borrow, to archive and research, to protect from conflict and export, and to store and catalog thousands of literary works for over four thousand years. Regardless of how we access literary works today, the fact that we may download them represents our current role in this ancient cultural practice.

What Do the Fable and Animal Tale Entail in Aesop’s Fables?

One of the world’s most famous collections of folklore is the classical collection of allegorical fables titled Aesop’s Fables. Like the poetry of Sappho, Aesop’s Fables only appeared in the texts of others – of Aristophanes, Plato, and Aristotle. While Hesiod, a contemporary of Homer, mentions a fable in Works and Days (700s B.C.E), no one is attributed. Its allegorical tales with animal characters are animal fables – also known as bestial fables.

Even its title was legendary. As fantastic as the tales themselves, it was popular belief that a historical Aesop had actually existed. He was a slave in Archaic Greece, around 600 B.C.E. and a well-known fabulist who retold fables to the ruling classes. It was through his storytelling talent that helped Aesop gain his liberty (OER). Regardless of the legend of a historical Aesop, the stories themselves are diverse and reflect both rural life and urban social norms and values with Eastern influences. What has come to us as Aesop’s Fables is more like a collection of fables with allusions to other literary works as an intertext.

In all actuality, the fables themselves were probably written down by 300 B.C. and represent many sources and variations of content, of what Perry describes as “an appropriative, adaptable, flexible, ‘monstrous and chaotic’ literary category” (Aesopica 2007). Unlike in our modern-day times when distinctions are made between fables and animal fables, Aesop’s Fables were a medley of stories featuring plants, gods, and personified characterizations, which are instances of anthropomorphism. Popular forms of fables – like Aesop’s Fables – attribute a didactic role for the fable to teach social norms, especially on human behavior. When the fables were eventually written down, its ‘style’ was determined in order to make them seem archaic and authentic, as instruction dictates.

The language (phrasis) should be very simple, straightforward, unassuming, and free of all subtlety and periodic expression, so that the meaning is absolutely clear and the words do not appear to be loftier in stature than the actors, especially when these are animals.(Nicolaus qtd. Lefkowitz)

What Roles Has the Fable Had Since Its Early, Ancient Origins?

Like the 1001 Nights, Aesop’s Fables was also known as ‘popular’ with ties to more ancient stories. The added moral endings of Aesop’s Fables show how these fables served to teach a social group.

“To be ‘humane’ (humanus) meant not only to be a human being but also to have exercised one’s capacity as a human being to the fullest through learning” (Christopher Celenza 2008).

Yet, another role of Greek fables was during eras of censorship. The fable served to avoid the censors. This is called Aesopian language, a writing style of the allegory to avoid detection. But as its own subgenre of folklore, differentiating between a fable, story, and parable is neither easy nor helpful.

For example, at a time when Greek citizens were censored in public speaking areas,

“The fables served as a means by which criticisms against the government could be expressed without fear of punishment. In effect, the stories served as a code by which the weak and powerless could speak out against the strong and powerful” (World Encyclopedia.org).

This role of the fable has also emerged in modern literature. For example, in the 1860s, the practice of Aesopian language was applied to circumvent censorship in Russian literature.

I spoke the language / of Aesop. / And what’s more, I astonished / Europe. / My bid for independence was / ill-timed. . . / They slapped their imprimaturs / on the press . . . And put one over on all Russia / to a man . . . / Well, what the . . . Am I really back / to Aesop? (S. Skitalets, as satire in 1907)

The use of Aesopian language is satirized by Russian novelist Nikolai Gogol in his story Nose (1836).

‘But what makes ту business unreasonable? It wouldn’t seem to be anything of the sort.’ ‘That’s the way you see it.’ ‘But look here, the same thing happened last week. A civil servant came in exactly as you have now, brought a hand-written note, the charge came to two rubles and seventy-three copecks, and all he wanted to announce was that a black poodle had run away. Ask yourself, what could be wrong with that? But it turned out to be libel; that so-called poodle was the treasurer of some institution, I don’t remember which one.’

How to Approach Fairy Tales through Ecocritical Textual Analysis

Similar to the ways Aesop’s Fables have been modified, so have other forms of folklore, including fairy tales.

For example, the 1812 publication of the Grimms’ Fairy Tales followed similar steps.

“These features form the basis that enables the tales to readily provide a good lesson or a use for the present” (Grimms’ preface 1812).

Modern-day storytelling traditions – either by publishing houses or stories told in our families – challenge literary studies to look at literature for what is told and not told.

For example, Junto Diaz, the author of The Wondrous Life of Oscar Wao (2007) and story cycle writer, takes notes of his role as a storyteller to address and un-silence culture’s narrative gaps known as critical fabulation.

“All societies are organized by the silences they need to maintain. I think the role of art is to try to delineate, break, and introduce language into some of these silences” (Marisol qtd. in Walsh).

Diaz’s approach also applies to ecocriticism, because as readers we may not notice the role and significance of nature in literature due to our own culture’s norms and ideology; hence, our social norms silence nature.

Current scholarship on the intersection of literature and nature is demonstrated through an ecocriticism study of the Brother Grimms and nature.

For example, stories like Old Mother Frost and The Three Snake Leaves show the “interconnectedness of nature and culture (Adler 2014):

From an ecocritical perspective, these tales depict the various manipulations of nature by humans, the moral consciousness formed by the symbiosis and dissonance between nature and culture, the responsibility of humans to respect and nurture nature (as well as the consequences of disrespecting the natural order), in addition to the power of nature to restore and damage human existence. (OER Adler 55)

To paraphrase Adler, what is being argued is that by an ecocritical reading of folklore – as in the tales of the Brothers Grimm – interpretations reveal humanity’s harm to nature and its dire consequences. Since humanity harms nature, nature cannot prevail and support our own health either. Hence, the web of life has been fractured.

Modern children’s literature is a body of written work with many instances and themes that touch upon dynamics between humanity and nature that are potentially fairer and more fruitful for literary studies in ecocriticism.

Activity

For example, in E.B. White’s Charlotte’s Web, the child Fern protests when her father decides to kill one of their livestock due to its size,

“Do away with it?” shrieked Fern.

“You mean kill it?

Just because it’s smaller than the others?”

The deliberate attention to the rights of animals continues in the dialogue between Charlotte and her father as she continues to protest: “Please don’t kill it!” she sobbed. “It’s unfair.”

Another animal fable with a similar ecocritical ‘ethos’ is “Old Sultan” from the Brothers Grimm’s story collection. An elderly dog named Sultan must demonstrate his usefulness to his owner to convince him he deserves to continue living:

“Then the shepherd patted him on the head and said,

‘Old Sultan has saved our child from the wolf,

and therefore he shall live and be well taken care of

and have plenty to eat.”

When we compare different traditions of animal fables, this comparative literary practice offers opportunities in the twenty-first century to learn about beliefs and social norms that support sustainable ideologies in the past. These comparative textual analyses assist in becoming more informed about ways to support sustainable measures and values.

How to Engage in a Textual Analysis on the Representation of Animals through Animal Studies

In his work on animal studies, Mario Ortiz-Robles points out that “some animals are more equal than others” in Orwell’s Animal Farm to affirm that literary studies must continue to work and understand representations of nature.

“We might yet learn to read allegory as a fundamentally political rhetorical figure through which our relation to animals is continually negotiated. We need literature to learn this impossible lesson” (Animal Studies 2016).

The literary theory known as animal studies specializes in intersections with animals and humans in literature. Scholars and critics like Algerian French philosopher Jacques Derrida apply this theory in their own work on topics to understand Western expressions of anthropomorphism in numerous types of texts. For example, in revisiting biblical scripture in Genesis, it has become apparent to Jacques Derrida that humanity’s role in naming the animals demonstrates an inherent hegemonic dynamic.

- “The animal is a word, it is an appellation that men have instituted, a name they have given themselves the right and the authority to give to another living creature” (Derrida 1997).

- Derrida defines ‘animal’ as a word that men have given themselves the right to give. His work on folklore also informs on the dynamics between humans and nonhumans in literary texts to address ideology.

- “We know the history of fabulation and how it remains an anthropomorphic taming, a moralizing subjection, a domestication. Always a discourse of man, on man, indeed on the animality of man, but for man and as man.”

Let’s work with the fables themselves to read them as anthropomorphic reflections of the Western storytelling tradition.

Animals and Aesop’s Fables

In the case of Aesop’s Fables most of these stories end with an inserted moral, and some are quite familiar to us, like “The Ants and the Grasshopper,” where the working insects prepare for future hardships and the grasshopper struggles because he did not ration. He did not plan. Other fables like “The Trees and the Axe” are quite deliberate in addressing the web of life, but its anthropomorphism seems to belittle the message.

“The Ants and the Grasshopper,”

The Ants were employing a fine winter’s day in drying grain collected in the summertime. A Grasshopper, perishing with famine, passed by and earnestly begged for a little food. The Ants inquired of him: “Why did you not treasure up food during the summer?” He replied: “I had not leisure; I passed the days in singing.” They then said: “If you were foolish enough to sing all the summer, you must dance supperless to bed in the winter.”

Idleness brings want.

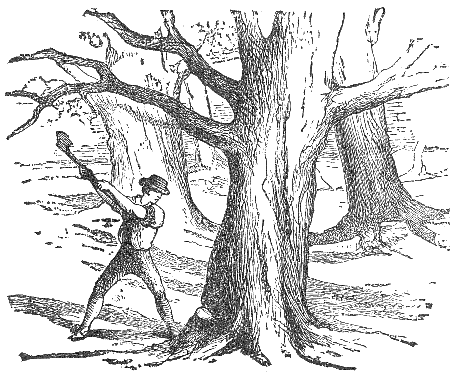

“The Trees and the Axe”

A Man came into a forest, and made a petition to the Trees to provide him a handle for his axe. The Trees consented to his request, and gave him a young ash-tree. No sooner had the man fitted from it a new handle to his axe, than he began to use it, and quickly felled with his strokes the noblest giants of the forest. An old oak, lamenting when too late the destruction of his companions, said to a neighboring cedar: “The first step has lost us all. If we had not given up the rights of the ash, we might yet have retained our own privileges and have stood for ages.” OER Gutenberg “Aesop’s Fables” In yielding the rights of others, we may endanger our own.

“The Monkey and the Camel”

The beasts of the forest gave a splendid entertainment, at which the Monkey stood up and danced. Having vastly delighted the assembly, he sat down amidst universal applause. The Camel, envious of the praises bestowed on the Monkey, and desirous to divert to himself the favor of the guests, proposed to stand up in his turn, and dance for their amusement. He moved about in so very ridiculous a manner, that the Beasts, in a fit of indignation, set upon him with clubs, and drove him out of the assembly.

It is absurd to ape our betters.

Now, let’s compare animal fables: one from Aesop and the other from another tradition. Here is a Native American mythological story by the Cherokee with the fable “The Rat and the Elephant.” How do the two different traditions of fables represent animals? OER folktale by Cherokee

“The Rat and the Elephant”

A Rat, traveling on the highway, met a huge elephant, bearing his royal master and his suite, and also his favorite cat and dog, and parrot and monkey. The great beast and his attendants were followed by an admiring crowd, taking up all of the road. “What fools you are,” said the Rat to the people, “to make such a hubbub over an elephant. Is it his great bulk that you so much admire? It can only frighten little boys and girls, and I can do that as well. I am a beast; as well as he, and have as many legs and ears and eyes. He has no right to take up all the highway, which belongs as much to me as to him.” At this moment, the cat spied the rat, and, jumping to the ground, soon convinced him that he was not an elephant.

Because we are like the great in one respect we must not think we are like them in all.

Topics relevant to twenty-first century sustainable goals from Aesop’s Fables like those outlined by the United Nations (UNSDG) include life on land and below water, gender equality, reducing inequality, sustainable communities and cities, and quality education.

Key Points

- Folklore is a collective ancient storytelling culture, like early hymns and oral epic narratives

- Folklore by its forms, like the animal fable, mythology, allegory, and fantasy, teaches, is didactic

- Aesop’s Fables are featured and set in rural regions with symbolic characterizations

- Folklore reflects instances of anthropomorphism in Western fables and animal tales

- Ecocritical perspectives of folklore unveil silences and efforts to censor folk culture

Media Attributions

- Life of Aesop © Wikipedia is licensed under a CC0 (Creative Commons Zero) license

- Aesop and red fox figure © Wikipedia is licensed under a CC0 (Creative Commons Zero) license

- Hercules and the wagoner © Wikipedia is licensed under a CC0 (Creative Commons Zero) license

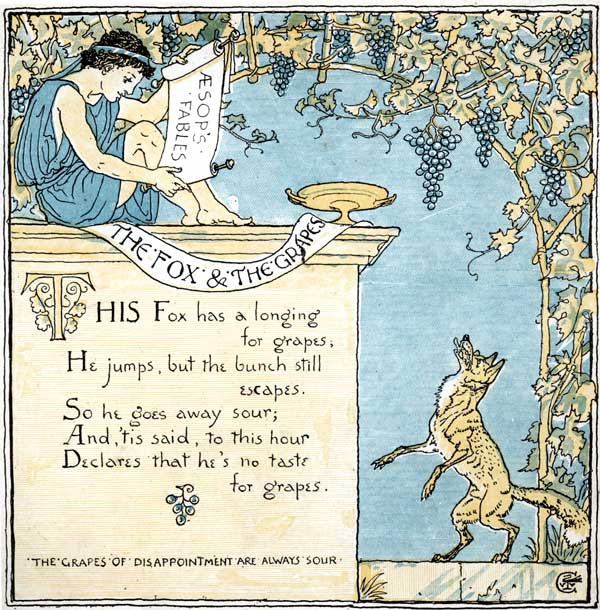

- The Fox and the Grapes © Wikipedia is licensed under a CC0 (Creative Commons Zero) license

- The Trees and the Axe © The Project Gutenberg is licensed under a CC0 (Creative Commons Zero) license

- The Monkey and the Camel © The Project Gutenberg is licensed under a CC0 (Creative Commons Zero) license

- The Rat and the Elephant © The Project Gutenberg is licensed under a Public Domain license

Definitions of literature range from ’written’ works of poetry, the story, the narrative, film, and dramatic works – with numerous subgenres – to including any written, spoken, or otherwise recorded work like podcasts, and radio. Works of literature are frequently categorized in a genre that reflects a specific form. The tradition of designating a genre dates back to Aristotle’s Poetics in 335 B.C.E. Since the late 1990s in academia, definitions of literature include two more designations – ‘popular’ and ‘serious’ literature, as in commercial or traditional and canonical works. Cherokee First Nations and Indigenous scholar Daniel Heath Justice recognizes the “privileged status that literature holds in the Western tradition as ‘serious’ literature, which resonates associative binary and colonial legacies of “civilized and savage” treatment of a people and their literature (Justice 2018). Yet, Justice also acknowledges that, along with other social groups, representing a culture with their own literary tradition empowers their communities, regardless of the privilege of canonical works. Any literature course should utilize works of literature that have been canonized alongside uncanonized works. Some texts are traditionally canonized – like Ovid’s Metamorphosis (6 C.E.) and Ben Jonson’s Volpone; Or the Fox (1606). But, others have only been recently incorporated – like the hymns of Enheduanna, Sappho’s poetic fragments, and Arabian Nights. This last one originates from a complex Persian and Middle Eastern literary tradition that has been historically viewed as popular, until recently (Horta & Seale 2022). As Justice affirms, “Literature as a category is about what’s important to a culture, the stories that are privileged and honored, the narratives that people – often those in power, but also those resisting that power – believe to be central to their understanding of the world” (Justice 20). For more information, visit OER On Literature.

A Greek poet as significant as Homer on the legacy of Greek mythology. He wrote the first known Farmer’s Almanac with wise sayings that Benjamin Franklin emulates in his work. Hesiod wrote poetry, on agriculture, early Greek astronomy, and economic theory. Like the Sumerian poet Enheduanna, he is the first known Greek poet who viewed his work as ‘an individual’.

A poem, narrative, or other types of texts like art and film with symbolic significance is allegory. The whole narrative of allegorical poetry, for example, – its storyline, characters, and setting – is not to be understood literally, but symbolically, especially of characters as personification. Famous allegories include Aesop’s Fables and John Bunyan’s The Pilgrim’s Progress (1678). The allegory is not to be confused with the satire, like George Orwell’s Animal Farm (1945). The symbolism of an allegorical story may also operate through anthropomorphism, like nonhuman figures in animal fables. Animal characters with human-like attributes symbolically express a certain meaning. Plants also have allegorical meaning. For example, the “Rose” in the medieval allegory The Romance of the Rose symbolizes a young maiden through the personification of this botanical plant. Plato’s “Allegory of the Cave” (Republic 380 B.C.E) is understood more as a thought experiment (OER source). The theoretical work of a philosopher is symbolically represented by Plato’s allegory to explain the role of the philosopher: A philosopher learns from emotional and reactive thinking to rely on and utilize reason in order to understand the real reality beyond human sensory capabilities. For more information, visit OER Allegory of the Cave.

This animation shows how human understanding directly relates to lived experiences CC

This image is of a colorful, artistic cartoon-like representation of the myth of the cave. It simply shows how our own direct experiences limit our understanding. To demonstrate this idea, the left-most portion of this image has an orange wall with shadows projected onto it. In front of these shadows are three men sitting on the floor in chains. They are shown reaching out their arms out toward the shadows as if the shadows were real. Behind the men’s backs is another wall, a yellow brick wall. The source of the shadows comes from this wall where three women in lavender dresses hold up three objects whose shadows project onto the far wall by a live fire, like puppetry. The women hold a Greek soldier, a horse, and a fox. Next to the row of women is a large cauldron, a large pot with flames overflowing it, as its sight source. The flames are bright white, yellow, red, orange, and blue, with an ashy gray trail of smoke lingering at the ceiling of the cave. On the right-side of this representation of the myth of the cave shows two men outside the cave. They realize that the shadows are caused by a fire. One of the men holds his hand over his eyes for shade and the other holds his hand out, palm facing up, to show confusion. This whole scene demonstrates the initial understanding we hold as true by our own direct experiences as we gradually grow from simple cause and effect assumptions to further realizations of the complexities of reality, which must be known through further observation, inquiry, and critical thinking, as well as evidence (Book VII of Plato’s The Republic Wiki).

A collection of stories with many contributors, Aesop’s Fables and Arabian Nights are two examples of an intertext. Intertexts in our times refer to building an understanding of a topic in one text by also working with several other related texts. Intertextuality is considered to mean the shaping of meaning that also relies on multiple and related texts, like the series of stories found in the New Testament, for example.

Representations of the cosmos, animal characters, fantastic deities, and objects like robots in both Western and Eastern texts with human-like characteristics are instances of anthropomorphism (OER on Robots as 'human-like'). Anthropomorphism is also witnessed in religious texts to present divine-like qualities to humans, as the demigods in Greek mythology, Egyptian, and India’s mythology. Its opposite is known as theomorphism, when humans have god-like characteristics like in scripture: “Anthropomorphism ascribes human and nature to the divine”(A WordPress glossary). Yet, Native American literature does not fit this general construction of nature. Their stories allow the animal kingdom to simply be while humans coexist nearby.

A form of writing to avoid censors of aesopic stories. Its tales are written in a style akin to Aesop’s Fables.

Critical fabulation is an instance of a silenced character in any piece of literature, yet narrative gaps also exist in a family’s storytelling tradition.