Chapter One: On How the Ancient Hymn Intersects with Gender & Inequality

Outcomes and Skills Practiced

- Close reading & textual analysis of early poetry where poetic devices emerged

- Identify and negotiate roles of metaphor and mythological figures in the hymns

- Develop close reading skills to explicate texts through activities & assignments on key passages

…a scientific understanding of nature, [provides an] advocacy of nonhuman species and indictment of those who destroy the legacy of the land.

Williams 124

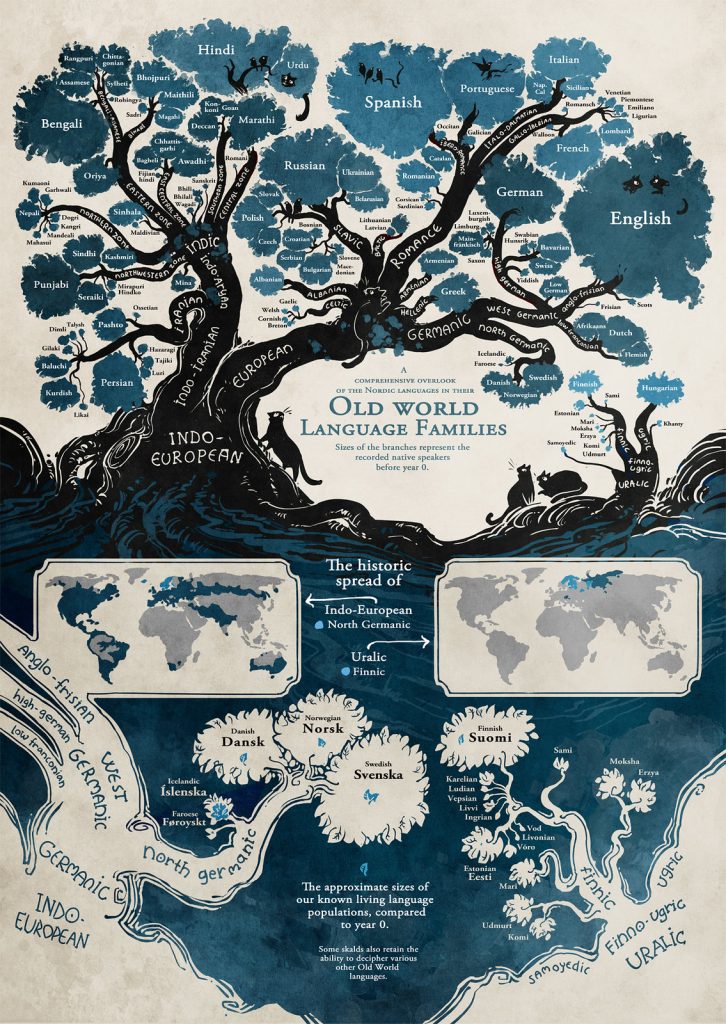

PIE Tree (Proto-Indo-European languages) shows our native languages overlapping to create new versions. CC (Wiki)

Introduction of Chapter One

What Are Early Forms of Song and How Do They Reveal Challenges for Sustainability?

The previous section introduces this first part and its three chapters by featuring the poetic element of the folk song, identifying themes, and recognizing common literary tropes and symbolism. Let’s continue to build on what literary texts are composed of what some call the ‘ingredients of literature’, by focusing on poetry and the poetic elements of early religious songs – namely hymns. The themes of featured songs are relevant to our present day, including topics on equality and sustainable communities, which are also addressed by the United Nations Sustainable Development Goals (UNSDG).

Early, ancient forms of the song are featured in this chapter to demonstrate our rich legacy of poetic devices. Ecocritical readings of these early songs will also be featured to support student learning and to encourage student engagement through close reading, analysis, and interpretation assignments on early samples of verse. At the end of this chapter, the short writing exercises are designed to inspire further inquiries concerning sustainability, especially in the literature of ancient civilizations that have come and gone, but whose legacies continue to live on in their cultural and linguistic influences and artifacts, like the first book ever known to humanity, the Epic of Gilgamesh.

The first known writer in human history who signed her name to her own work is the Akkadian priestess and poet Enheduanna. Enheduanna resided in the City of Ur, Sumer and lived over four thousand years ago. The hymns attributed to her predate the Epic of Gilgamesh by over one thousand years. Clay tablets with cuneiform writing of her hymns reflect poetic devices: a narrator, invocation to a deity, setting, meter, and tone, in addition to those named in the previous section. Here are the opening lines of one of her hymns.

How Do Enheduanna’s Hymns Reflect Today’s Challenges?

Outcomes and Skills Practiced

- To practice close reading skills to identify cultural and religious icons and allusions of mythological figures, like gods and goddesses in early Sumerian hymns and early lyrical poems.

Hymns are early versions of songs and poetry told in religious settings but can represent the emotions, thoughts, and worries of its communities. They are recited in oral societies with an oral tradition and are written down by early societies that developed literacy. The early hymns attributed to Sumer’s Priestess Enheduanna seem personal and dire.

It was in your service

That I first entered

The holy temple,

I, Enheduanna,

The high priestess,…

These opening lines express Enheduanna’s role in religious songs. In an intimate and personal tone, the lines express events in the past by the verb “was” and the first-person subject pronoun “I.” Let’s look further into the work of Enheduanna. This close reading of her hymn addresses the theme and possible intersections on any aspect of sustainability.

Intertext

How do Enheduanna’s Hymns Express Aspects of Sustainability?

Outcomes and Skills Practiced

- To practice close reading skills to identify cultural references to nature and intersections with sustainability, via ecocriticism in Sumerian hymns, early lyrical poems.

Let’s look further into the same hymn. Through its first-person narrator, the lines below express concerns about political alliances and regional divisions. It is as if Enheduanna shares her own personal testimony on the consequences of belonging to an empire that is expanding, as opposing forces respond. The result is her exile. This hymn has a narrator who pleads to the Sumerian moon goddess Inanna.

I, Enheduanna,

The high priestess,

I carried the ritual basket,

I chanted your praise.

Now I have been cast out

To the place of lepers.

A close reading of these lines inspires our inquiries about aspects of the culture of the empire Enheduanna was born into. She aligns her loyalties with the empire since she was the daughter of its ruler, Sumerian King Sargon Akkad. Like an ode, this hymn praises goddess Inanna, whom the narrator has served. The poetic devices of this hymn have literal and figurative significance. She compares her exile with dispossessed “lepers” and the “ritual basket” emphasizes Enheduanna’s unbreakable devotion to Inanna. In exile, Enheduanna writes devotional hymns to affirm her role and legitimacy as the priestess to the Temple of Ur and to regain fortune.

Ecocritical interpretive approaches can assist in a further understanding of early, ancient forms of literature in regard to nature. For example, the consequences of land acquisition by the empire destabilized its civilization. Inquiries about the dependence on natural resources as inexhaustible can inform unsustainable practices.

Historians have sought a fruitful path of inquiry in literary studies by ecocriticism. With Enheduanna, they focus on her role as the priestess of the empire. They describe her contribution to peacemaking, Goal 17 of the UNSDG on peace and social justice.

“These hymns re-defined the gods for the people of the Akkadian Empire under Sargon’s rule and helped provide the underlying religious homogeneity sought by the king. For over forty years Enheduanna held the office of high priestess, even surviving the attempted coup against her authority by Lugal-Ane” (World History).

While peace was achieved, its cost was the implementation of homogeneous measures. Shown in other hymns attributed to Enheduanna, this means that the deities of the opposing communities were incorporated into Sumerian mythology, the storytelling tradition of the dominant culture. Is this act of appropriation truly a sign of solidarity? Perhaps not. But the fact still remains. Peace prevailed for forty years. And Enheduanna, as her writing shows, is credited as a contributor to peacemaking efforts, which is a topic in the United Nations Sustainable Guide (UNSDG). Representations of political structures are prevalent in the mythology and scription of other civilizations.

Here is another example of a non-Homeric hymn from Hesiod’s Theogony. It honors the birth of the Greek goddess Hecate, whose mother is Asteria (star) and her father Perses (destroyer; ravager). Through Hecate’s role and abilities, Hesiod’s hymn displaces patriarchal rule and hierarchy.

For as many as were born of Gaia and Ouranos amongst all these, she [Hecate] has her due portion. The son of Kronos did Her no wrong nor took anything away of all that was Her portion among the former Titan Gods: but She holds, as the division was at the first from the beginning, privilege both in Earth, and in Heaven, and in Sea. OER on Greek Pantheon & Birth of Hekate

Hecate in this hymn by Hesiod is connected to earth, sky, and sea. A close reading of this hymn offers insights into Greek culture such as the practice of magic because one of Hecate’s talents is the power of sorcery. Sorcery in Western tradition is feminized and attributed to female mythological figures – like Circe. She, like other female supernatural figures like Persephone and Medea, represents the movement of nature, the cosmos, and the life cycle. Shakespeare’s three Weird Sisters in Macbeth also allude to these earlier representations (Pressbooks on “Macbeth”).

Let’s proceed and work with other hymns by Enheduanna.

Key Points

-

Early hymns can inform its poetic qualities and personal testimonies

-

Ecocritical readings enhance these initial readings

-

Other hymns also reveal cultural norms like the practice of magic

Media Attributions

- Minna Sundberg – Language Tree © Tom Wigley via. Flickr is licensed under a CC0 (Creative Commons Zero) license

(“eco” in Greek is household, ecology is the learning of the life of populations)

What is ecocriticism? At first sight, it is simply a literary theory to learn about nature in literature; when critics approach literature to learn about nature, they are offering ‘ecocritical’ interpretations. Ecocriticism aims to not reduce nature into a concept or social construct, which the Western tradition shows in the majority of its literary traditions. Literary studies offers a platform to learn about representations of nature in texts, while analyzing themes on social injustices, which may share similar treatments, since “ecocriticism is a theory that seeks to relate literary works to the natural environment” (Estok 2005). Another explanation is “the study of the relationship between literature and the physical environment” and “takes an earth-centered approach to literary studies” (Glotfelty and Fromm 1996). Another explains that, “Ecocriticism examines the representation of and relationships between the biophysical environment and texts, predominantly through ecological theory” (Chisty 2021). Since the 2000s, ecocriticism has relied on scientific and philosophical approaches to understand humanity’s place in the world. The UNSDG offer a wide-ranging view of aspects of human’s roles to address current injustices and the climate crisis. Partly, it is “committed to effecting change by analyzing the function – thematic, artistic, social, historical, ideological, theoretical, or otherwise – of the natural environment.” Ecocritical readings on environmental injustices can intersect with social injustices, like Langston Hughes’ poem expresses. *Go to the section on Langston Hughes’ poem A Dream Deferred in the introduction of this book. This class supports intersections between social injustices and environmental ones. The work of Joni Adamson, American Indian Literature, Environmental Justice, and Ecocriticism: The Middle Place (2001) features the literatures of Indigenous communities and literary analyses with ecocritical understandings to address and expose Western abuse of nature and the causes of our current environmental crises, while demonstrating the literary and storytelling traditions of Indigenous communities as ‘an alternative’ theory. For more information, visit OER on Ecocriticism. This literary theory stems from the first wave of environmentalism in the U.S. by ecofeminism. The term ecocriticism emerged in the article Literature and Ecology (1978) by William Rueckert and an earlier work in 1972 by William Meeker The Comedy of Survival: Studies in Literary Ecology. “First wave" environmental criticism concerns itself with conventional nature writing and conservation-oriented environmentalism, which traces its origins to the work of Ralph Waldo Emerson, Henry David Thoreau, and John Muir. "Second wave" environmental criticism redefines the environment in terms of the seventeen Principles of Environmental Justice and increasingly concerns itself with "issues of environmental welfare and equity" and "critique of the demographic homogeneity of traditional environmental movements and academic environmental studies” (17 Principles of Environmental Justice). A modern third wave of ecocriticism recognizes ethnic and national particularities and yet transcends ethnic and national boundaries; this third wave explores all facets of human experience from an environmental viewpoint” (Adamson 2009). Originally, ecocritics looked at the relationship between literature and nature – between culture and the global environment. Literature shows human tendencies to anthropomorphize nature. Ecocritics see culture as hierarchical and in contrast to nature, especially in Western texts. To analyze this relationship, nature needs to be distinct from human constructs: the wilderness, scenic sublime, countryside, and domestic picturesque. Man-made factors are social orders and political constructs like culture and poverty. Yet, the ‘setting’ of narratives may also be fantastic – as in folklore, the gothic, and science fiction, and hence is also fertile soil for ecocritical readings. Ecocriticism takes as its subject the interconnections between nature and culture, specifically the cultural artifacts of language and literature. As a critical stance, “it has one foot in literature and the other on land; as a theoretical discourse, it negotiates between the human and the nonhuman" (Glotfelty and Fromm qtd. in Sandner 2000). The roots of the environmental movement can be traced back to the abolition movement, which revealed the connections between colonization, conquest, slavery, resource exploitation, and capital, and many of the most successful strategies of early environmentalism were borrowed from the abolition, civil rights, and women's movements and American Indian Land Claims lawsuits. For this reason, “any history of environmentalism that did not include W. E. B. Du Bois, Rosa Parks, Martin Luther King, Jr., or Cesar Chavez, among others, would need to be revised” (Adamson 2009).

Common contemporary usage of the word “myth” means something which is a popular claim, but is not true. In Literary Studies, mythology – like origin stories – refers to epics from oral traditions; a few examples include Sumerian Epic of Gilgamesh, The Iliad, and the Mayan Popol Vuh. Mythology originates from shorter stories, as in fable-like stories and legends and folktales, that were later compiled to create a cohesive narrative. Ancient mythology is intricately part of a social group’s religious cult. Part of folklore, mythology is a storytelling tradition tied to religious doctrine. All of the world’s mythology was polytheistic, as witnessed in Greece, Roman, and Norse mythology, and may have changed, like the Torah, in Christian bibles, and the Quran. Mythology is sustained by its culture and their community’s oral and practicing rituals and religious tradition. Stories on creation, key creators as gods, and supernatural beings are represented throughout world mythology. At times, humans and deities coexist, which is also a major trope in mythology. For more information, visit OER Pressbooks on World Mythology.

A Greek poet as significant as Homer on the legacy of Greek mythology. He wrote the first known Farmer’s Almanac with wise sayings that Benjamin Franklin emulates in his work. Hesiod wrote poetry, on agriculture, early Greek astronomy, and economic theory. Like the Sumerian poet Enheduanna, he is the first known Greek poet who viewed his work as ‘an individual’.

culture is a multi-dimensional construct of social cohesion defined by English anthropologist Edward Taylor in 1871 as learned behavior, which contrasts colonial, essentialist, and race-ignorant views of culture as ‘biological traits’ (OER). Visit Key Terms for more details.