Chapter Seven: Sustainability Intersections & Early Modern English Theater

Outcomes and Skills Practiced

- Build familiarity with Elizabethan dramatic works, including the allegory, satire, and mock epic

- Identify literary and poetic devices in drama, like the allusion, the unities, and the soliloquy.

- Practice textual analysis of allegorical characters in satire & consider ecocritical approaches.

On the Historical Context of Elizabethan England

When Elizabethan theater arose out of medieval theater in the 1500s, Western thought in Europe had been shifting. The impact of the Protestant Reformation challenged the Catholic Church’s static placement of humanity toward the top of the Great Chain of Being and the discoveries of Copernicus and Galileo propelled a scientific and technological revolution. English colonialism also enhanced and began to expand across the Atlantic and the African Continent to influence the Transatlantic Slave Trade, an expansion to the West Indies by the Portuguese, Spanish, English, Dutch, and French.

“The 1588 English defeat of the less armed Spanish Armada marked the beginning of the British global presence, starting with the Caribbean” (Illik 2006).

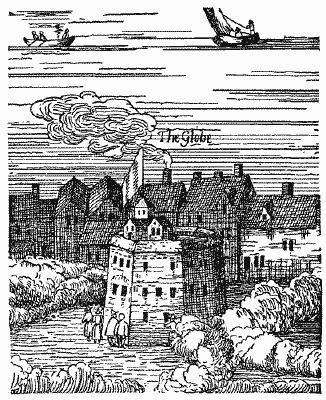

Resembling a remnant of heliocentrism, the globe of the Earth became an English icon of colonialism when Sir Francis Drake’s 1580 circumvention around the earth and the sun demonstrated English maritime presence that rivaled Spain. European education was also shifting since the advent of the Renaissance, and by the late 1500s in England as well.

“English grammar schools and university students studied extensively the plays of Plautus and Terence” (Devlin 2017).

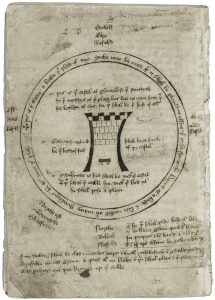

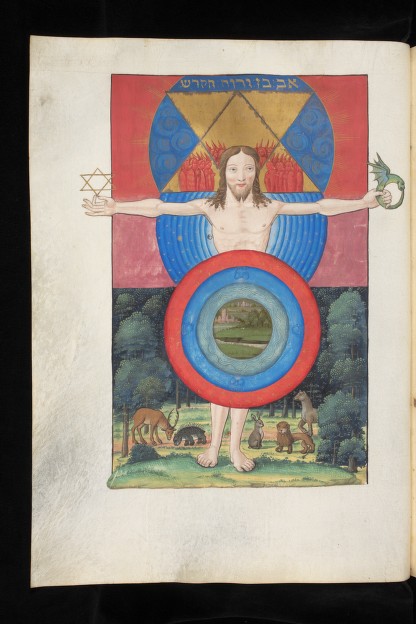

Definitions and understandings of humanity had been changing as well from medieval notions of the human soul, demonstrated in Introduction of the Kabbalah by Reverend Jean Thenaud’s illustration (see below).

1536 illustration from Introduction to the Kabbalah by Jean Thenaud, Bibliothèque de Genève, pour e-codices 2008. CC

On Elizabethan and Jacobean Drama and its Classical Influences

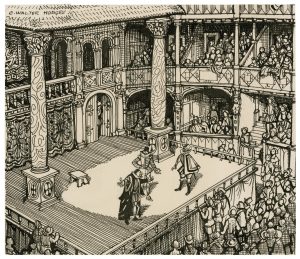

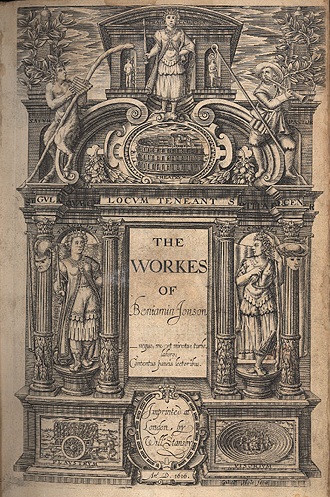

1558 Queen Elizabeth’s coronation, 1600 Rose Theater where Ben Jonson began his career, and Jonson’s 1616 Folio. CC

English Renaissance theater arose during the reigns of Queen Elizabeth I (1558–1603) and James I (1603–1625). The milieu of London’s theater district thrived by the 1590s, along the Thames River. Several theaters in this district in London, England produced theatrical works and performances by playwrights like William Shakespeare, Ben Jonson, and Christopher Marlowe, including The Rose Theater, The Children’s Royal Chapel, The Globe, and Fortune Theater. These theaters were close to other public attractions like outdoor public pulpits where people gathered to listen to Protestant sermons. Close by were underground meeting houses that drew in religious dissenters.

In addition to English historical chronicles, the European Renaissance inspired Elizabethan dramatists to incorporate classical literature for their subject matter and literary aesthetics and theory. However, there were also influences from medieval miracle plays and Roman playwrights and poets like Seneca, Virgil and Ovid. Classical and Near East story collections also influenced Elizabethan drama with allusions to Aesop’s Fables and the One Thousand and One Nights throughout the plays. By the late 1590s, Elizabethan dramatists modified Aristotle’s unities from Poetics and adopted the classical narrative structure of five acts. By the early 1600s, English Renaissance literature “derived from Horace’s dictum in Ars Poetica that poetry should mix the useful with the sweet” (Greenberg 15). Theatrical productions are usually set in classical history or outside of England, while themes address close to home concerns.

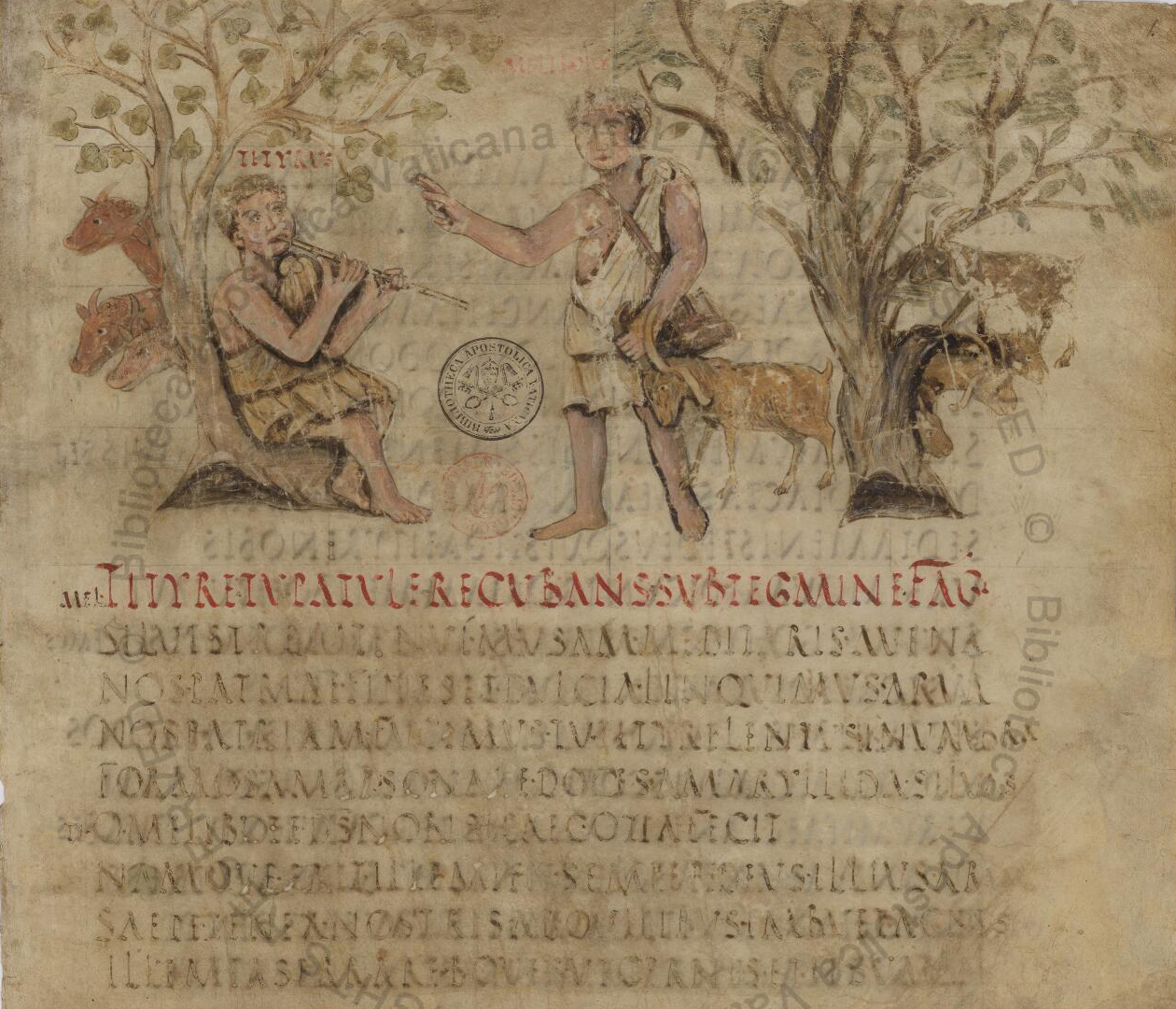

Roman Mosaic with Clio, Muse of History (left), Shakespearean actors (center), and Virgil 400 C.E. (right) CC

On Classical and Christian Symbolism in Elizabethan Theater

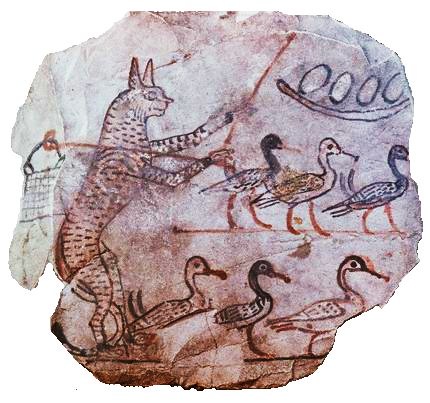

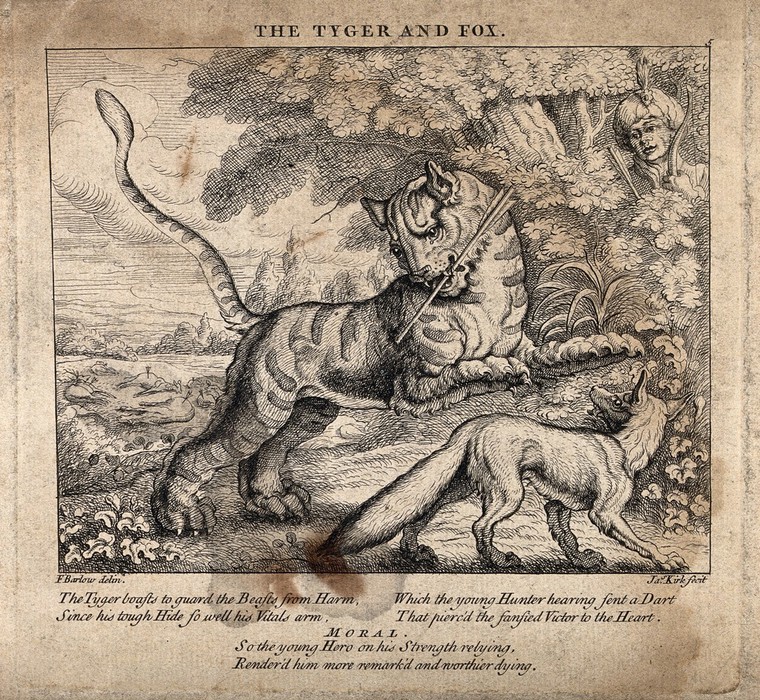

Classical symbolism in Elizabethan theater is witnessed by the presence of animals, which can be allusions to Aesop’s Fables. Throughout Elizabethan theater, classical symbolism means more than just to symbolize immoral human behavior. Their representation greatly contrasts animal symbolism in earlier medieval morality plays and the classical allegory, which are understood as instances of anthropomorphism in classical Western culture. For example, one main purpose of animals in Aesop’s Fables is to both elevate human morality and supremacy and degrade animals, especially domestic livestock and forest animals. Elizabethan dramas differ in the form and purpose of the presence of animals as metaphor and allusion; meaning the use of anthropomorphism differs from classical literary works.

Serving as figurative language, the presence of animals in English dramas, while representing remnants of the classical animal fable, can serve to critique questionable moral centers of key human characters, which are not conveniently attributed to animals. And these criticisms can also translate into social critiques of human moral supremacy and disillusionments of humanism during the English Renaissance. One form and purpose of the presence of animals in English drama is through the role of bestial nomenclature through characterization.

For example in Ben Jonson’s Volpone; Or the Fox (1606), the names of human characters show a preoccupation with Elizabethan forms of greed. Roguish scoundrels in the play are given Italian animal names: Corvino, Voltore, and Corbaccio. In English these names mean “crow,” “vulture,” and “raven” — allegorical characters who are animals in classical fables. But in Jonson’s play, these are the names of human characters.

“A crucial question in staging the play, as in reading it, is how to balance the beast-fable allegory drawn from Aesop and suggesting by the names and behavior of many of the characters with realistic human psychology” (Watson xi).

Bestial nomenclature connotes not just trickery, but corrupt, selfish, and dishonest human qualities. Allusions from classical animal fable allusions demonstrate ideas about humanity, like preoccupations with urban wealth and morality in early modern society.

Throughout Elizabethan drama, Christian symbolism from Christian mythology is represented by the presence of the snake, a key figure in the Garden of Eden. In this tradition, the snake symbolizes a break from a timeless sense of nature and the cosmos to the physical cycles of life on Earth. Through Eve, the serpent initiates the beginning of the fall of humanity on Earth. In world mythology, the snake in storytelling traditions serves as both a literary trope and an archetype. As a trope, snakes help humanity to make sense of the links between physical aspects of nature and the abstract, unknowable mysteries of reality.

In ancient stories, representations of snakes are archetypal. The biological shedding of its skin symbolizes renewal and the temporality of life. Their presence reflects aspects of our emotional psyche that have experienced transformations, from a zygote into a multicellular embryo and then into a human infant. Throughout our lives, we continue to undergo transformations at critical stages of development.

Snakes also represent the fertility of the planet and are represented as the female gender who reproduces. In Volpone, or the Fox, by Ben Jonson the costume of Mosca is “snake-like” in many of its productions, which serves to highlight his immoral role in the play. Through Catholic symbolism, the serpent epitomizes immorality. Since Genesis, the snake as Satan represents humanity’s sins.

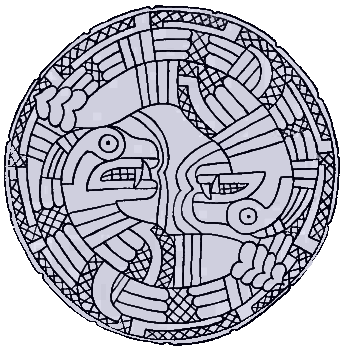

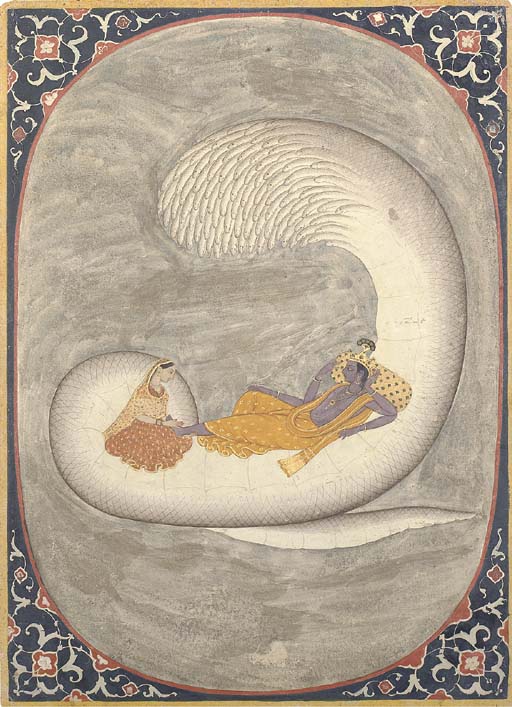

Twin snakes, North of Mexico (left), Snake Naga shields Buddha (left), 580 B.C.E. Gorgon (right), and 1700s Vishnu (far right) CC

On Elizabethan Theater and Satire

Satire in one shape or form is in our daily lives, from comics and television series like I Love Lucy, Saturday Night Live, The Simpsons, Chappelle’s Show, and The Daily Show to novels by Voltaire, Austen, Gogol, and Orwell to filmed or live stage performances by George Carlin, Richard Pryor, Margaret Cho, and Sarah Silverman. Weaved in their wordplay of puns, pranks, and jokes are opportunities for audiences to hold their tongues to critically reflect while engaging in collective laughter. Traditionally, the ‘canonical model’ of satire does not just “identify vice and folly but aims to reform” (Greenberg 2019).

A common trope in satire is social criticism. This is presented by reference to characterization — like the fool, clown, trickster, rascal, and rogue, for example. A well-known satire is the mock epic by Alexander Pope titled The Rape of the Lock (1712) that inspired the satirical bildungsroman Gulliver’s Travels (1726) by Jonathan Swift and Voltaire’s novella Candide (1759).

“But the mock epic is not only a discrete subgenre; it can also be a satiric technique. It can function locally as well as globally. It occurs whenever a satirist uses heroic language to treat unheroic events” (Greenberg 39).

Stemming from classical satire and influences of picaresque novels like the anonymous Spanish novela The Life of Lazarillo de Tormes (1554) or Miguel de Cervantes’ Don Quixote (1604) with lowly roguish or idealistic protagonists, numerous forms of satire have emerged throughout different literary traditions, cultures, and historical epochs.

For example, many well-known satires represent low status rascals and idealistic protagonists:

- Satirical picaresque The Adventures of Huckleberry Finn (1887) by Mark Twain inducted American literature to the tradition of satire and humor

- Satirical film by Charlie Chaplin imitates Hitler in The Great Dictator (1940)

- Satirical science fiction blends wit with social critiques in Douglas Adams’ The Hitchhiker’s Guide to the Galaxy (1978) and Robert A. Heinlein’s Starship Troopers (1959)

- Satirical novels like Sir Salman Rushdie’s Satanic Verses (1988)

When we think of ‘satire’, there are certain characteristics that seem universal:

- It is a public artistic mode or genre that relies on dramatic irony.

- Its vast variations as a literary mode and definitions include how satire shares traits with allegory in representation, symbolism, and moral purpose, and at times transformative.

- Its facade of social reform: As social criticism, Jonathan Swift noted that “readers have an uncanny ability to deflect satirical criticism away from themselves and onto others” (Greenberg 2019).

In early modern drama, satire operated through comedy with themes on domestic and common life.

Two 1200s-1100s BCE Egyptian satirical ostraca (left), English Satire Punch (center), & 2007 spoof of A Midsummer Dream CC

On Ben Jonson’s Satire in Volpone; Or the Fox

After his satire Volpone; Or the Fox (1606) debuted, Ben Jonson became the most celebrated English Renaissance dramatist and poet, second to Shakespeare.

Volpone opened at the famous Globe Theater in 1606. The same cast that performed Shakespeare’s masterpieces of that period had recently performed Shakespeare’s Othello, also set in Venice. For 180 years following Volpone’s successful debut (except when the Puritans closed the theaters from 1642 to 1660), it was frequently in performance — long after most other Jacobean plays had been forgotten. (Watson 2019)

Ben Jonson’s Volpone; Or the Fox is an allegorical satire set in Venice, Italy, which coincidentally is the homeland of the Renaissance. Throughout the play’s plot and subplots, its main characters — ‘protagonist villains’ — con inheritance hunters, a practice known in Rome as trickery. Yet, Jonson’s satirical humor also serves as a philosophical basis to his comedy. This is accomplished through characterization.

He wanted to bring in a vital realism. He aimed at discipline, inventing it with realism, in short to mix profit with pleasure. He drew his characters by observing Puritan London. In the medieval past in the Latin world, the ancient concept of ‘humor’ was popular. Static types like the jealous husband, the stern father and cunning servant were used in Morality plays. Jonson’s comedies were concerned with these weaknesses, holding them to ridicule.(Greenberg 2019)

Writing and producing his dramatic works during “a period of extraordinary change in English society,” Jonson approached his dramas to address social criticism through allegorical satire and reached his audiences to “express the complexities of life and truth in a form that could be appreciated by the common man” (Griffiths qtd. in Hazzard).

The characters in Volpone; Or the Fox fall prey to corruption of this city by the two main villains of the play, Volpone (Sly Fox in Italian) and his foil Mosca (Fly in Italian). The conflict of the play is established in its opening scene through characterization and plot design, on the theme of urban corruption and immorality. It also sets up Jonson’s allegorical satire through dramatic irony, because while his audience responds to the immorality of its two principal characters, they also ruminate on their own moral compasses. Hence, Jonson provides insights on the problems of the day by adapting the popular ‘legacy hunters’ tale. The opening scene shows Volpone’s obsession with wealth and unveils its blinding effects.

VOLPONE: Good morning to the day; and next, my gold:

Open the shrine, that I may see my Saint.

[MOSCA WITHDRAWS THE CURTAIN, AND DISCOVERS PILES OF GOLD, PLATE, JEWELS, ETC.]

Hail the world’s soul, and mine! more glad than is

The teeming earth to see the long’d-for sun

Peep through the horns of the celestial Ram,

Am I, to view thy splendour darkening his;

That lying here, amongst my other hoards,

Shew’st like a flame by night; or like the day

Struck out of chaos, when all darkness fled

Unto the centre. Gutenberg version of “Volpone; Or the Fox”

Through allegory and satire, Jonson’s characterization of Volpone is extravagant. His excess is in both wealth and a lack of a moral compass.

“When, in the opening monologue of Ben Jonson’s Volpone, the title character prays to his hoard and compares the gleam of his gold to the first glow of light in the creation of the universe, he is elevating money to the level of the divine, calling attention to his (unheroic) greed” (Greenberg 39).

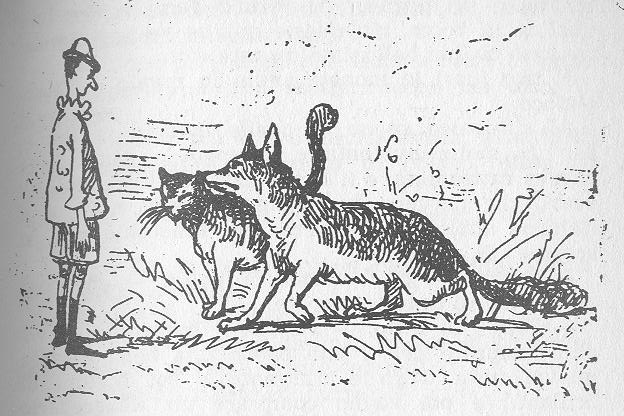

1800s Fox in Pinocchio (left) and 1600s Aesop’s Fables’ The Fox and the Crane & The Tiger and the Fox (center and right) CC

On Theme and Allusion in Ben Jonson’s Volpone; Or The Fox (1606)

Jonson’s use of allegory and dramatic irony also alludes to the theme of the systemic culture of greed in urban settings, whose scale goes beyond simply accumulating wealth, “but to all objects of our desires” (Greenblat). Through allegorical satire, Jonson transforms his drama into multidimensional social critiques on contemporary hypocrisy, greed, and abuse of power.

While the Church formally denounced trade and usury and glorified poverty, Leonardo Bruni (d. 1444), the Florentine Chancellor, formulated a defence of acquisition of wealth. He used Aristotle and Juvenal to prove that poverty distorts and demeans but the wealthy man alone could be in a position to exercise virtue. “From then onwards humanists provided citizens with a reasoned defence of riches…(Hay qtd. in Bhattacharya)

Unlike the corrupt and inhumane superstructure within royal families where both Hamlet and Hermione suffer moral injustices in Shakespeare’s tragedy Hamlet (1599) and in the comedy The Winter’s Tale (1610) respectively, Jonson’s comedy implicates any character. Critics argue that Jonson satirizes contemporary English society, especially Protestant England.

“Venice built its economy and identity entirely around exchange. So, it provides a perfect setting for a sophisticated understanding of greed as desire that has broken loose from real objects and real needs — an apt lesson for Jacobean London, which was rapidly moving from a feudal system toward a capitalist one” (Watson xix).

On the Role of the Animal Fable in Volpone; Or the Fox

Scholarship on the intersection between biblical scripture and the representation of nature by ecocritics Armbruster and Wallace in Beyond Nature Writing (2001) enhance literary studies on ethics, because Elizabethan dramatists, like Ben Jonson, also address concerns surrounding morality and organized religion through allusion and the animal fable.

Jonson in Volpone; Or the Fox enhances negotiations on morality by its classical allusions like the animal fable, at a time when Renaissance humanism emerged in England and Christian religious doctrines were controversial.

For example, instead of simply presenting an allegory, Jonson uses allegorical elements in Volpone; Or the Fox (1606) to satirize humanity’s obsession with newfound wealth; avarice — an urban cultural trend associated with and attributed to non-Christians throughout Europe.

The animalistic side to the play enables you to develop a very visual, sensuous way of delineating the characters. By drawing on both their animal qualities and the commedia dell’arte [early comic form of Italian drama] tradition you can create a rather alarming, exotic, fun kind of world for both the characters and the audience. The animalistic side in the play encourages actors to explore their characters’ obsessional drive and the ways in which they are both blinkered in what they want and the way in which they prey on each other. (Director Hersov qtd. Watson xi)

In doing so, Ben Jonson’s comedy is less like an allegory and more like satire, because its allusions of bestial allegory exposes the inhumanity of its human characters. Jonson inverts classical anthropomorphism. While the animal fable in Aesop’s Fables rely on what is disassociated from humans — animals, Jonson exposes the inherent degrading influences of excessive wealth in his own work. The fascination with excessive wealth in Jonson’s play dehumanizes them, as stated by Marion Robles Ortiz. The representation of animals, if anything, is about how humans became human. Jonson’s play simply puts up a mirror for the audience to see their own animality.

“…where the animality of animals is not the obverse of civilization but its raison d’être. Civilization, in this reading, is that compensatory effort made by slow, brainy primates with little fur and unremarkable sense of perception to make due in a world full of wild animals whose ‘pure talents’ we both fear and secretly covet” (Robles Ortiz 72).

A play disguised as an allegorical animal fable, Jonson’s Volpone offers a social critique of the temptations of wealth in Protestant England. Mosca, the fly, rhetorically deceives everyone and leads them to their own downfalls, including that of his master Volpone, the fox. Volpone’s humiliation of himself is the play’s climax. The use of allegory creates a sweetness of satire by its laughter and lightness, while reserving the bitterness of satire to sink into the intellects of the audience. Yet, unlike “The Fox and the Grapes” in Aesop’s Fables, Jonson’s use of allegory does not resolve; “in the end, the world the play inhabits will continue to be guided by avarice” (Ortiz Robles 69). At the end of Volpone; Or the Fox (1606), Jonson reinforces his moral message through animal imagery.

Throughout the play’s plot, Jonson’s two main characters attempt to transform themselves by accumulating wealth only to subvert their own morality; and, even their humanity. No growth ensues. The main character Volpone represents a degenerate early modern version of the classical allegorical fox. Jonson’s allegorical dramatic satire critiques social norms throughout its society whose ideology encourages and sustains greed and rewards wrongdoing, such practices that will spread to an insatiable scale and threaten the society itself, as colonialism gains momentum in the 1600s.

How does Elizabethan Theater Inform Ecocriticism?

Jonson’s Volpone; Or the Fox is fruitful for ecocriticism. Ecocritical approaches can further inform how the play represents human greed and corruption through the representation of nature. Recent ecocritical studies on the Elizabethan dramatic works of Ben Jonson and Shakespeare, among others, build on earlier studies on the representations of nature throughout the setting of the nonhuman aspects of nature.

For example, current literary ecocritical approaches to Shakespeare’s The Tempest build on American literary critic Leo Marx’s 1964 seminal study of Shakespeare’s The Tempest in The Machine in the Garden (1964). Not only do ecocritics address the actual torrent in The Tempest, but they also demonstrate intersections between 1600s English colonial projects with recent atmospheric disruptions due to climate change. Ecocritics — like dramatists — read ‘the storm’ in metaphorical terms to understand an ecological imbalance.

“Leo Marx (1964) proposed that William Shakespeare’s tragicomedy The Tempest (1611) be considered an allegory for the New World, in the midst of the social and cultural upheaval of the 1960s” (Gray 2020).

Not only has Shakespeare based his entire play on the aftermath of a hurricane in the Caribbean, but he also negotiates characterizations to represent how to regulate English civility, while tempering the erratic state of nature through Ariel and Caliban, otherworldly creatures native to the island.

“The Tempest functions as an ambiguous allusion troping the blessed isle’s nightmarish inversion from pastoral to industrial” (Lanone 2008).

Throughout Elizabethan drama, themes also address the intersection between social regulation and human behavior through trickster characterizations and animal fable and classical mythology — like Robin Goodfellow in Shakespeare’s A Midsummer Night’s Dream and Volpone in Jonson’s Volpone; Or the Fox (1606).

On Humanism and Ben Jonson’s Volpone; Or the Fox

Coined in the 1800s as Renaissance humanism, England’s Elizabethan and Jacobean theater also underwent a humanistic revival that was informed by Greek and Roman literature, like Roman poet Virgil. Virgil’s works were greatly revered throughout the European Renaissance, especially for their themes on human ‘civic’ (public) virtue — a perspective on secular society that both intrigued and inspired Renaissance playwrights and poets alike — especially Ben Jonson.

In the Aeneid, human ‘civic’ virtue is demonstrated throughout Virgil’s literary epic, while it celebrates Emperor Augustus’ values of social order, loyalty, and public virtue. Classical humanists also viewed humanity as reigning supreme, demonstrated by 340 B.C.E. Aristotelian philosophical scheme, known as the Great Chain of Being; a worldview Renaissance philosopher René Descartes later developed an understanding of its scala naturae in the 1500s (Pressbooks on Descartes).

By 1637, Descartes embraced Aristotles’ views of the ‘ladder of being’ to equate human thought as the substance of life itself, as cogito, ergo sum — I think, therefore I am. Modifying classical humanism, Descartes fundamentally privileges the mind over the body, a hierarchical positioning of the human mind to determine human nature, through our rational capacities. Cartesian dualistic thinking ensued.

Dualism in worldviews and on human nature has challenged the viability of ecocriticism, since nature and culture, humanity and the nonhuman, the body and mind are interconnected and of equal importance: “they constantly mingle, like water and soil in a flowing stream” of the web of life (Armbruster and Wallace 2001).

Ben Jonson’s allegorical satire interrogates the elevation of the human mind over the human heart in his play Volpone; Or the Fox through cunning. Its two main characters dress in different disguises throughout the play. Along with elements of classical allegory in his comedy, Ben Jonson also utilizes rhetorical deceptions and camouflages in characterization to present themes on morality. The conceit of shapeshifting of identities in order to trick others extends to the victims, who also ‘play act’. This extended metaphor exposes the harm avarice causes to human integrity. Through characterizations that utilize human reason to engage in a comedy of false impressions, Jonson satirizes Renaissance humanism and its ideals of human rationality. In doing so, his dramatic work offers new ways for audiences to negotiate morality and new ways to reflect on how to treat one another and nature more fairly. “This conceit allows Jonson’s comedy to satirize avarice as a form of ‘rare punishment’ to itself since no one is spared from the fox’s wiles, least of all the big fox himself” (Ortiz Robles 69).

On Ben Jonson’s Humanism and Ecocriticism

Scholars in literary studies turn to key Elizabethan comedies for ecocritical interpretations of early modern drama like Shakespeare’s A Midsummer Night’s Dream (1605) and Ben Jonson’s Volpone; Or the Fox (1606). Their works are fruitful for ecocriticism and animal studies since their plays are early modern renditions of humanism with classical allusions to works like Aesop’s Fables and Ovid’s Metamorphoses. Ecocritic Alex Guerrero discusses the interplay between the urban and the wilderness in A Midsummer Night’s Dream by Shakespeare to show the primacy of Gaia: “…what is not disputed is the influence of the forest and the faeries over the Athenians” (Guerrero 2017). This reading of Shakespeare’s work suggests an inherent awareness of humanity’s placement among nature itself. In Jonson’s Volpone; Or the Fox, ecocritics address the play’s preoccupation with human subjectivity and the animal fable. “Literature serves to separate humans from animals but also to confuse and conflate them” (Otiz Robles).

For example, ecocritic Iovino sheds light on how critical approaches to Jonson’s play broaden literary studies on humanism in Jonson’s Volpone. Like Ortiz Robles, Iovino also focuses on these possibilities in Jonson’s Volpone to understand the human-nature binary. What has ensued are findings of the elevation of the human mind over the human heart, as a source of a lack of cohesion; symmetry among humanity and nature; Cartesian dualism. Iovino argues that ecocriticism can offer new ways to address the intersection between social and environmental injustices, especially in understanding discourses on ‘otherness’.

Can ecocriticism indeed be a ‘discourse on the human’? And how might the idea of Otherness (an Otherness more radical than the socially constructed one) play a role in this “discourse on the human,” an implicit—and yet essential—concept in ecological culture? (Iovino 2010)

Iovino’s concerns reflect similar questions posed by Black writers and literary theorists like Toni Morrison. Morrison also recognizes that institutional racism has been established and sustained by forms of language usage that ‘others’ people, as a way to legitimize racial prejudice and to exile them or exploit them. In Western culture, ‘othered’ groups of people are given associations of ‘animal-like’ characteristics.

For example, Toni Morrison also identifies the intersection between the ‘othering’ of nature and humanity.

“Since the law deprived slaves of property and instead made them into property, their condition resembled that of an animal and not a human being” (OER African American History Pressbooks).

Morrison also explains in Playing in the Dark (1992) that the roots of the racializing of a group of people into a legal and social construction to legitimize slavery stem from the rise of the Enlightenment, which was informed by Cartesian dualism.

For example, “slavery was enforced upon colonized indigenous people throughout the Americas and such practices spread to an international scale through the human trafficking and enslavement of the peoples of the African continent” (Morrison 1992).

Morrison’s awareness of forms of race-based othering, of racism, and of its brutal and sadistic injustices, simulates the disregard of nature, too, which is a focus in animal studies.

“…in the West, the advent of industrialized modernity was decisive for the history of animals…when animals became objects of human manipulation” (Robles Ortiz).

Since Elizabethan and Jacobean theater reflect a literary tradition that coincidently emerged along with Cartesian dualism, literary and ecocritical approaches to Ben Jonson’s Volpone; Or the Fox can be telling of the dramatist’s concerns during English Renaissance humanism. By his use of classical allusions, Ben Jonson exposes the profound cost to social justice and social order: greed.

On Ben Jonson’s Volpone and Ecocritical Interpretations

Traditionally, the animal fable in literature represents the frailties of human behavior. Yet, ecocritics and philosophers have also worked with the animal fable in the story compilations of Aesop’s Fables and the Arabian Nights to learn about the animal fable as a subgenre of folklore born out of the domestication of wild animals into farm animals.

For example, feminist philosopher Kate Soper addresses human legacies of the practice of husbandry that places its animals within a regulated worldview that defines nature, nonhumans, not only as valuable for the livelihood of humans, but also as products to be consumed, a practice in the twentieth and twenty-first centuries that has nothing to do with sustenance or survival.

The call to consume less is often presented as undesirable and authoritarian. Yet, the market itself has become an authoritarian force — commanding people to sacrifice or marginalise everything that is not commercially viable; condemning them to long hours of often very boring work to provide stuff that often isn’t really needed; monopolising conceptions of the ‘good life’; and preparing children for a life of consumption. We need, in short, to challenge the presumption that the work-dominated, stressed-out, time-scarce and materially encumbered affluence of today is advancing human well-being rather than being detrimental to it. (Soper 2023)

Ben Jonson’s Volpone; Or the Fox demonstrates this acute awareness as well.

For example, observe the passage below from this satirical drama and note that its references to animals are quite different from the typical animal fable. Close read the passage and make queries like, What is Jonson’s use of animal fables in his satirical drama?

“I use no trade, no venture; I would no earth with plough shares; fat no beasts/To feed the shambles; have no mills for iron,/Oil corn, or men, to grind em into poulder” (I.i,33-36).

Jonson’s play has transformed the typical animal fable into a satire to critique human tyranny.

Through an intelligent anti-heroic protagonist with wit to trick characters with insatiable avarice for material wealth, Jonson’s play exposes how human corruption is self-destructive. The play becomes an allegory of destructivity on a global scale by passages that refer to domestic power and greed abroad.

“There are metaphors here — the wounded earth, the feeding of the slaughterhouses and the grinding of men to powder” (Brockbank 1988).

The exploitation of all resources emerges as the theme behind the immorality of human corruption. Thousands of years of human activity has transformed wild animals. And this very same activity also transformed us. Humanity has become the dominant species of the world. This awareness of our impact and power over nature is witnessed in ancient epics and theological parables from the East and West. Animal fables instruct on how nature was brought into human civilization.

Topics relevant to twenty-first century sustainable goals from Jonson’s Volpone; Or the Fox (1606), like those outlined by the United Nations (UNSDG), include life on land and below water, gender equality, reducing inequality, sustainable communities and cities, quality education, responsible production and consumption, and good health and well being.

Born in 1572, Ben Jonson rejected his father’s bricklaying trade and ran away from his apprenticeship to join the army. He returned to England in 1592, working as an actor and playwright. In 1598, he was tried for murder after killing another actor in a duel over the play The Isle of Dogs (1597) with Thomas Nashe, and was briefly imprisoned, One of his first plays, Every Man Out of His Humor (1599) had fellow playwright William Shakespeare as a cast member. His success grew with such works as Volpone (1605) and The Alchemist (1610). He is considered a very fine Elizabethan poet. Ben Jonson is regarded as the second most important English dramatist, after Shakespeare. Volpone whilst being a satirical comedy can be considered a beast play, as all the principle characters are people, but have animal names and display characteristics of the animals they represent. Jonson was a Renaissance dramatist and poet and was concerned with classical precedent. In 1597, while in prison, he converted to Catholicism. In Volpone, the unities of time and place are observed, but the action is complicated by a subplot.

Key Points

- Featured history of English Renaissance, as a latecomer to the European Renaissance

- Addressed innovations that shaped Elizabethan culture & theater

- Highlighted classical & Christian allusions and symbolism

- Focused on Jonson’s Volpone; Or the Fox, on classical references, Aristotle’s Poetics, & allegorical satire

- Addressed humanism and ecocriticism and animal studies, via allegory & satire in comedy

- UNSDG highlights concerns with responsible production and consumption, life on land, among others

Media Attributions

- 1400s Staging of a Morality Play © Wikipedia is licensed under a Public Domain license

- View of an Elizabethan Stage © Wikipedia is licensed under a CC0 (Creative Commons Zero) license

- Swan Theater in London © Windward Community College is licensed under a CC BY-NC-SA (Attribution NonCommercial ShareAlike) license

- Introduction to the Kabbalah © e-codices is licensed under a CC BY-NC (Attribution NonCommercial) license

- Elizabeth I in Coronation Robes © Wikipedia is licensed under a CC0 (Creative Commons Zero) license

- The Rose Theater © Wikipedia is licensed under a CC0 (Creative Commons Zero) license

- Title page of The Workes of Benjamin Jonson © Wikipedia is licensed under a CC0 (Creative Commons Zero) license

- Shakespearean Actors © Norwegian Digital Learning Arena is licensed under a Public Domain license

- Ancient North American serpent © Wikipedia is licensed under a Public Domain license

- Gorgon © Wikipedia is licensed under a Public Domain license

- Ananta Vishnu © Wikipedia is licensed under a Public Domain license

- Punch © Wikipedia is licensed under a Public Domain license

- The Fox and the Cat © Wikipedia is licensed under a CC0 (Creative Commons Zero) license

- Fox and Crane © Francis Barlow, ca. 1626–1704 is licensed under a Public Domain license

This tradition is driven by Europe and surrounding cultures and its colonies. Influences by Greek philosophers and European philosophers shape ideology and collective understanding of the world and lived experiences, including classical and modern notions of what it means to be human. Humanity is defined as a political animal (Aristotle), and later associated with an animal that has a soul (Descartes), with potential, a promising animal (Nietzsche), and with modern “time-keeping” abilities (Heidegger).

In the European Middle Ages, the ‘Great Chain of Being’ represents a neo-platonic understanding of the cosmic order. This view is borrowed from Aristotle, but includes a blend of Christian theology where motion is controlled by the Christian God through orders of angels; “heaven and earth are intimately connected” (Joseph 2005). A Western notion of scala natura, or grand scheme of the universe, the Great Chain of Being is a hypothesis of cosmic order that places all natural phenomena and humans in a hierarchical order of spiritual inferiority to superiority. Classical views of the Great Chain of Being associate the lower forms as ‘lifeless’. This cosmic order is understood as a series of planes whose ascension is toward Platonic “perfect forms,” where they ascend toward their sources within a Ptolemaic (Earth at the center), geocentric view of the universe.

unities, according to Aristotle’s Poetics (350 B.C.E.) addresses the timeline of a Greek theatrical work. Visit Key Terms for more details: *Aristotelian unities.

A symbol is an object, expression or event that represents an idea beyond itself. The weather and light/darkness will often have a symbolic meaning. Survey of Native American Literature: Symbols in Literature

Animals in literature serve to make distinctions “between the human and non-human.” Hence, the study of animals in literature, like in the work of Mario Ortiz Robles in Literature and Animal Studies (2017), addresses the presence of animals in literature. This serves to “show us how to be human.” Animals in literature, like in origin myths, also represent aspects of nature dominated by humanity. Theorists outside animal theory, like Derrida, may also reflect on the Western division between humans and other life forms: “The distinction between humans and non-humans is a ‘figment of our imagination’ – a rigid binary.” This binary operates within colonialism in Daniel Defoe’s Robinson Crusoe (1719), according to Ortiz, where the success of its protagonist depends on domesticating animals on the island.

Allegorical tales in Western folklore with Near East influences preserved in a compilation of stories is called Aesop’s Fables (300 BCE). In classical Greek and Roman storytelling traditions, Aesop’s Fables represent folklore as popular allegorical and animal fables with symbolic characters and inserted morals (Encyclopedia of Philosophy, peer-reviewed doc). Its tales grasp a vast subject matter and literary tropes: On tropes of Aesop's Fables. Another well-known compilation is One Thousand and One Nights.

Representations of the cosmos, animal characters, fantastic deities, and objects like robots in both Western and Eastern texts with human-like characteristics are instances of anthropomorphism (OER on Robots as 'human-like'). Anthropomorphism is also witnessed in religious texts to present divine-like qualities to humans, as the demigods in Greek mythology, Egyptian, and India’s mythology. Its opposite is known as theomorphism, when humans have god-like characteristics like in scripture: “Anthropomorphism ascribes human and nature to the divine”(A WordPress glossary). Yet, Native American literature does not fit this general construction of nature. Their stories allow the animal kingdom to simply be while humans coexist nearby.

In literary texts, in common speech, and in performative pieces like poetry and theater, metaphor is a form of a figure of speech where two or more elements of a different nature are compared with each other, but without “like” or “as.” If the comparison includes “like” or “as,” this form of a figure of speech is known to be a simile.

when a literary work references a person, place, event, or from another literary work. Visit Key Terms for more details.

figurative language means uses of language that are not meant to be interpreted and understood in literal terms. For example, the American phrase, ‘the apple of my eye’ has the “apple” as a symbol, which is a form of figurative language. Visit Key Terms for more details.

Humanism is understood as a concept that denotes many aspects of the European renaissance, a cultural revival movement. Specifically, though, humanism signifies the human as a master of his universe; where we can seek within ourselves for answers while we also appreciate our shortcomings and inner contradictions. Humanists placed humanity’s life at the center but still advocated Christian values. Humanism also reflects moral philosophy, history, poetry, and language aesthetics. Unlike Puritanism, humanists were more concerned with intellectual development and less about the immorality of the soul. They valued early antiquity and Christianity while critiquing medieval culture and society. Education was key, as was the matter of virtue (masculine power as moral). Becoming learned served your virtue. Michel Montaigne considered himself a humanist whose philosophical concerns resided on morality.

In Athenian theater, dramas are performed with a clear setting, adhered to the unities, and were performed by actors of the male gender. Greek theater originated from religious cults whereby audiences were directly engaged. Remnants of these cults are the Chorus and the purpose of the tragedy (OER). In Elizabethan drama, “Characterization is the fundamental and lasting element in the greatness of any dramatic work. Play does not owe its permanent position in literature to the quality of plot.”

Common contemporary usage of the word “myth” means something which is a popular claim, but is not true. In Literary Studies, mythology – like origin stories – refers to epics from oral traditions; a few examples include Sumerian Epic of Gilgamesh, The Iliad, and the Mayan Popol Vuh. Mythology originates from shorter stories, as in fable-like stories and legends and folktales, that were later compiled to create a cohesive narrative. Ancient mythology is intricately part of a social group’s religious cult. Part of folklore, mythology is a storytelling tradition tied to religious doctrine. All of the world’s mythology was polytheistic, as witnessed in Greece, Roman, and Norse mythology, and may have changed, like the Torah, in Christian bibles, and the Quran. Mythology is sustained by its culture and their community’s oral and practicing rituals and religious tradition. Stories on creation, key creators as gods, and supernatural beings are represented throughout world mythology. At times, humans and deities coexist, which is also a major trope in mythology. For more information, visit OER Pressbooks on World Mythology.

A satire is a poem, story, narrative, artwork, or film, for example, exposes questionable social norms or practices in a subtle, concealed manner through allegory, an animal fable, or humor, for example. A satire can evoke humor but addresses serious topics, like Orwell’s Animal Farm (1945). A picaresque novel is also satirical through ‘roguish’ characters. Literary satirists in the Western tradition range from Aesop’s Fables to Greek and Roman satirists Lucian, Horace, and Petronius and Renaissance dramatists Shakespeare, Miguel Cervantes, and Ben Jonson. Enlightenment satirists and recent social critics include the work by Voltaire, Twain, and Ambrose Bierce. For an example of Edgar Allan Poe’s satirical novel, go to The Narrative of Arthur Gordon Pym of Nantucket (1838) OER Satire PYM by Matt Johnson, 2014.

in many cases throughout Shakespeare’s dramas and poems, evokes humor. A technique in literature through the power of words as in rhetorical arguments to engage the audience and entertain. Rhetorical examples include puns, wit, spoonerism, and phonetic mix-ups.

These are narratives that are satirical – meaning they address contemporary issues and criticism in an indirect, entertaining manner – yet, with roguish characters and its criticism is more scathing and focuses on the ‘corrupt’ nature of social norms like Miguel de Cervante’s Don Quixote (1604) and Ben Jonson’s Volpone and more recent works Mark Twain’s The Adventures of Huckleberry Finn (1887).

The theme of a narrative or a play is the general idea or underlying message that the writer wants to expose. In Elizabethan Theater, “John Milton states as explicit theme of Paradise Lost to 'assert Eternal Providence,/And justify the ways of God to men.' Some critics have claimed that all nontrivial works of literature, including lyrical poems, involve an implicit theme which is embodied and dramatizes in the evolving meanings and imagery” (OER Elizabethan Theater). Whether you define it as the overarching subject matter of a text or its message, identifying themes in literary studies establishes initial skills in describing, summarizing, and offering a commentary to a piece of literature, without additional theoretical approaches. Yet, some research is helpful - of its historical era, culture, and geographic region.

In a tragedy an innocent protagonist will be involved in escalating circumstances with a fatal result. The tragic development is either caused by a flaw in the character’s personality or by events that evolve beyond her, their, or his control. According to Aristotle, Greek tragedy’s catharsis allows audiences to express pent up emotions at a key placing of a plot whereby a sense of morals are reaffirmed through the convergence of the fall or suffering of the play’s protagonist, like King Creon, as the tragic hero his self-realization as the cause of losing his family in Sophocles’ Antigone (400 B.C.E).

A comedy in a book, play, story, or film engages audiences through expressions of trickery, wit, paradoxes, and even satire. One example is a well-known technique throughout William Shakespeare’s plays – mistaken identities and misunderstandings.

Intersectionality is the “study of overlapping, intersecting social identities and related systems of oppression, domination, or discrimination” (Syracuse University). Intersectionality was first posed on Langston Hughes poetry to highlight intersections between racism and the legacy of slavery with environmental exploitation and that of Black laborers, where learners can conduct further research on such overlapping topics. For example, learners can research Black oppression in the 1840s through the work of America’s first ‘Father of Black Nationalism’ Martin R. Delany, in order to learn about the effects of slavery, while researching Joni Adamson’s work on environmental devastation. Intersectionality is a concept coined by American law expert Dr. Kimberlé Crenshaw in a 1989 paper to address the oppression of African women to address that gender and racism are not “mutually exclusive categories of experience and analysis.” In legal matters, injustices on both gender and race are considered separately in the U.S. The tendency to simplify a composite of injustices that are all related is described as interpreting the law on a ‘single axis framework’ (on its history). To remedy this oversimplification, Crenshaw coins the idea of ‘intersectionality’ as an approach that recognizes the complex composite nature of an injustice that reflects several injustices at once. Her goal is to make Black women more visible and for the law to acknowledge their plight as women of color (Sociology & Intersectionality). Intersectionality is a lens through which you can see where power comes and collides, and where it interlocks. “It’s not simply that there’s a race problem here, a gender problem here, and a class or LBGTQ problem there. Many times that framework erases what happens to people who are subject to all of these things'' (Columbia Law School).

The fable is one example of a literary form of folklore, like the animal fable. The fable is witnessed in Aesop’s Fables from 600 B.C.E and other examples include those from India and the Middle East. Fables and the animal fable in particular can help us to conduct ‘ecocritical’ readings. Like the fairy tales and Arabian Nights, readers may experience and explore the non-human in the fable.

A poem, narrative, or other types of texts like art and film with symbolic significance is allegory. The whole narrative of allegorical poetry, for example, – its storyline, characters, and setting – is not to be understood literally, but symbolically, especially of characters as personification. Famous allegories include Aesop’s Fables and John Bunyan’s The Pilgrim’s Progress (1678). The allegory is not to be confused with the satire, like George Orwell’s Animal Farm (1945). The symbolism of an allegorical story may also operate through anthropomorphism, like nonhuman figures in animal fables. Animal characters with human-like attributes symbolically express a certain meaning. Plants also have allegorical meaning. For example, the “Rose” in the medieval allegory The Romance of the Rose symbolizes a young maiden through the personification of this botanical plant. Plato’s “Allegory of the Cave” (Republic 380 B.C.E) is understood more as a thought experiment (OER source). The theoretical work of a philosopher is symbolically represented by Plato’s allegory to explain the role of the philosopher: A philosopher learns from emotional and reactive thinking to rely on and utilize reason in order to understand the real reality beyond human sensory capabilities. For more information, visit OER Allegory of the Cave.

This animation shows how human understanding directly relates to lived experiences CC

This image is of a colorful, artistic cartoon-like representation of the myth of the cave. It simply shows how our own direct experiences limit our understanding. To demonstrate this idea, the left-most portion of this image has an orange wall with shadows projected onto it. In front of these shadows are three men sitting on the floor in chains. They are shown reaching out their arms out toward the shadows as if the shadows were real. Behind the men’s backs is another wall, a yellow brick wall. The source of the shadows comes from this wall where three women in lavender dresses hold up three objects whose shadows project onto the far wall by a live fire, like puppetry. The women hold a Greek soldier, a horse, and a fox. Next to the row of women is a large cauldron, a large pot with flames overflowing it, as its sight source. The flames are bright white, yellow, red, orange, and blue, with an ashy gray trail of smoke lingering at the ceiling of the cave. On the right-side of this representation of the myth of the cave shows two men outside the cave. They realize that the shadows are caused by a fire. One of the men holds his hand over his eyes for shade and the other holds his hand out, palm facing up, to show confusion. This whole scene demonstrates the initial understanding we hold as true by our own direct experiences as we gradually grow from simple cause and effect assumptions to further realizations of the complexities of reality, which must be known through further observation, inquiry, and critical thinking, as well as evidence (Book VII of Plato’s The Republic Wiki).

In literary works from the Western tradition, the definition of ‘human’ contrasts with nature, the nonhuman, due to Cartesian dualistic ideology. Yet, through multidisciplinary collaborations on climate, like between Anthropology, Environmental Studies, and World Literature, for example, inquiries about defining humans emerge. For example, Literary Studies and ecocritic scholar Lawrence Buell in Keywords for Environmental Studies (2013) inquires about such definitions in light of twenty-first century climate and sustainability challenges to “point to critical questions that must be asked and answered with regard to what it means to be ‘human’ and what it means to be in the multispecies relationships within the biosphere” (Buell qtd. in Keywords for Environmental Studies). Humans in contemporary scholarship should not be confused with posthuman in science fiction and transhumanism.

“A more or less systematic ordering of ideas with associated doctrines, attitudes, beliefs, and symbols that together form a more or less coherent philosophy or Weltanschauung for a person, group, or sociopolitical movement” (APA Dictionary qtd. BU Equity Guide). In schools of thought such as political science and psychology, ideology is addressed as a system of beliefs that underpins and sustains the form of a society. A school may be supported by an ideology of curricular vigor that rewards certain achievers. The economy of a country may be supported by a capitalist ideology. But, ideology is also understood through other worldviews and cultural norms, like those practiced by the Indigenous communities of the Americas.

(“eco” in Greek is household, ecology is the learning of the life of populations)

What is ecocriticism? At first sight, it is simply a literary theory to learn about nature in literature; when critics approach literature to learn about nature, they are offering ‘ecocritical’ interpretations. Ecocriticism aims to not reduce nature into a concept or social construct, which the Western tradition shows in the majority of its literary traditions. Literary studies offers a platform to learn about representations of nature in texts, while analyzing themes on social injustices, which may share similar treatments, since “ecocriticism is a theory that seeks to relate literary works to the natural environment” (Estok 2005). Another explanation is “the study of the relationship between literature and the physical environment” and “takes an earth-centered approach to literary studies” (Glotfelty and Fromm 1996). Another explains that, “Ecocriticism examines the representation of and relationships between the biophysical environment and texts, predominantly through ecological theory” (Chisty 2021). Since the 2000s, ecocriticism has relied on scientific and philosophical approaches to understand humanity’s place in the world. The UNSDG offer a wide-ranging view of aspects of human’s roles to address current injustices and the climate crisis. Partly, it is “committed to effecting change by analyzing the function – thematic, artistic, social, historical, ideological, theoretical, or otherwise – of the natural environment.” Ecocritical readings on environmental injustices can intersect with social injustices, like Langston Hughes’ poem expresses. *Go to the section on Langston Hughes’ poem A Dream Deferred in the introduction of this book. This class supports intersections between social injustices and environmental ones. The work of Joni Adamson, American Indian Literature, Environmental Justice, and Ecocriticism: The Middle Place (2001) features the literatures of Indigenous communities and literary analyses with ecocritical understandings to address and expose Western abuse of nature and the causes of our current environmental crises, while demonstrating the literary and storytelling traditions of Indigenous communities as ‘an alternative’ theory. For more information, visit OER on Ecocriticism. This literary theory stems from the first wave of environmentalism in the U.S. by ecofeminism. The term ecocriticism emerged in the article Literature and Ecology (1978) by William Rueckert and an earlier work in 1972 by William Meeker The Comedy of Survival: Studies in Literary Ecology. “First wave" environmental criticism concerns itself with conventional nature writing and conservation-oriented environmentalism, which traces its origins to the work of Ralph Waldo Emerson, Henry David Thoreau, and John Muir. "Second wave" environmental criticism redefines the environment in terms of the seventeen Principles of Environmental Justice and increasingly concerns itself with "issues of environmental welfare and equity" and "critique of the demographic homogeneity of traditional environmental movements and academic environmental studies” (17 Principles of Environmental Justice). A modern third wave of ecocriticism recognizes ethnic and national particularities and yet transcends ethnic and national boundaries; this third wave explores all facets of human experience from an environmental viewpoint” (Adamson 2009). Originally, ecocritics looked at the relationship between literature and nature – between culture and the global environment. Literature shows human tendencies to anthropomorphize nature. Ecocritics see culture as hierarchical and in contrast to nature, especially in Western texts. To analyze this relationship, nature needs to be distinct from human constructs: the wilderness, scenic sublime, countryside, and domestic picturesque. Man-made factors are social orders and political constructs like culture and poverty. Yet, the ‘setting’ of narratives may also be fantastic – as in folklore, the gothic, and science fiction, and hence is also fertile soil for ecocritical readings. Ecocriticism takes as its subject the interconnections between nature and culture, specifically the cultural artifacts of language and literature. As a critical stance, “it has one foot in literature and the other on land; as a theoretical discourse, it negotiates between the human and the nonhuman" (Glotfelty and Fromm qtd. in Sandner 2000). The roots of the environmental movement can be traced back to the abolition movement, which revealed the connections between colonization, conquest, slavery, resource exploitation, and capital, and many of the most successful strategies of early environmentalism were borrowed from the abolition, civil rights, and women's movements and American Indian Land Claims lawsuits. For this reason, “any history of environmentalism that did not include W. E. B. Du Bois, Rosa Parks, Martin Luther King, Jr., or Cesar Chavez, among others, would need to be revised” (Adamson 2009).

The concept of nature is a social construct with qualifiers that make nature idyllic, or ‘balanced.’ Yet, in non-Western literary traditions, references to nature reflect real lived experiences, immersed in nature. For example, in Indigenous oral traditions, nature is dynamic. Adamson explains, “They tell of wars, crisis, and famine…they learned to live with ambiguities, to see the patterns, and to mimic natural processes in the cultivation of their gardens” (Adamson 56). Ecocritics and environmental humanists, among other scholars, witness humans as also a social construct in opposition to nature, or the nonhuman, which is witnessed throughout literature. Instances of the feminization of nature are understood as gendered ethnocentric views of nature by those who define humanity as superior to nature, and the masculine gender as superior to the female gender. These social constructions suggest anxieties about what it means to be human and overlap with discourses on power and colonialism when the colonized are effeminate, along with the conquered landscape. The gendering of a people and nature acts as a mechanism that initiated modernity, inequalities ecofeminist Soper addresses, “given the widely perceived parallels between the oppression of women and the destruction of nature” (Soper 1995). Feminist philosopher Kate Soper also argues on how nature is an ‘otherness’ in What is Nature: Culture, Politics, and the Non-Human (1995) to focus on Western attitudes from two schools of thought, on ecology and cultural criticism - that of our current climate crisis and efforts to address this crisis while understanding “the politics of the idea of nature,” on the semiotics of ‘nature’. Intersections between perception of nature and theories of sexuality offer insights into ‘the politics of the idea of nature.’

Before modern philosophy, the process of gaining knowledge was understood by relying on Aristotle’s form of logic. Aristotle’s form of logic applied deductive reasoning to formulate conclusions based on assumptions. This form of logic is known as syllogism, and this method of attaining knowledge was grounded in ancient empiricism, a belief that knowledge is attained by sense-experience.

Aristotle and Poetics; Aristotle was a student of Plato, who shared his criticism of early poetry: Greek drama, the epic, and lyrical poetry in what has become to be known as Poetics (335 B.C.E.). Visit Key Terms for more information.

In the Cartesian tradition of Western religious thought the body and soul are understood as separate. This duality is an example of Descartes' understanding of humanity as a spirit, affiliated with the immortal soul, and the body with the finite, or death. Rene Descartes also asserted that animals have no consciousness, unlike humanity. Descartes as the father of modern philosophy introduced the idea that humanity is distrustful or critical of sensory experiences and of the human imagination, meaning that scientific observation is not entirely objective. Empiricism was greatly critiqued by Descartes. For more information, visit OER Pressbooks on Cartesian Thought.

culture is a multi-dimensional construct of social cohesion defined by English anthropologist Edward Taylor in 1871 as learned behavior, which contrasts colonial, essentialist, and race-ignorant views of culture as ‘biological traits’ (OER). Visit Key Terms for more details.

According to ecocritic Lawrence Buell’s definition of ecocriticism, which involves the philosophical view that “human being and human consciousness are thought to be grounded in intimate interdependence with the nonhuman living world,” this “interdependence” is the web of life (Buell 2011). According to Danel Wildcat and Dine Deloria Jr. – whose son is currently History faculty at Harvard Dr. Philip Deloria (wiki on Philip Deloria), the worldview, the metaphysics of Indigenous peoples in North America experience reality as ‘related,’ the world is unified, and all aspects have significance and share a commonality among the tangible, spiritual, intelligent, and intangible. “The teachings of the tribe are almost always more complete, but they are oriented toward a far greater understanding of reality than is scientific knowledge”(OER Pressbooks on Indigenous Education, go to Ch. 9). As a more thorough and intuitive philosophy, they expose the limitations and exclusionary culture of Western culture and its reliance on Cartesian dualistic philosophy: “We live in an industrial, technological world in which a knowledge of science is often the key to employment, and in many cases is essential to understanding how the larger society views and uses the natural world, including, unfortunately, people and animals.”

An elaborate, extended metaphor, often found in poetry. In Ben Jonson’s comedy Volpone; Or the Fox, the characterization of the main villain involves ‘play acting’ to trick other characters, who also have to ‘put on an act’ as co-conspirators.

A formal academic discipline, Literary Studies seeks to understand literature in its totality through its disciplinary subsets like literary history, literary criticism, literary theory, schools of thought, and multidisciplinary scholarship like Gender Studies, Cultural Studies, and Film Studies. As an academic discipline, engagements in Literary Studies always look into language usage in literary history and literary traditions. “Literary Studies is concerned with the ways that language is used. If it isn’t concerned with language use, it isn’t Literary Studies. Literary Studies is about the ways in which writers use the formal resources of literature to represent and comment upon life” (Aphorisms on Literary Studies). A Literary Studies course with an ecocritical interpretative approach aims to learn from different disciplines and various literary traditions. Its purpose is to expand traditional literary inquiries in order to articulate more concrete understandings of the human-nature binary, environmental challenges, and social justice. These intersections allow learners to identify representations of nature to investigate cultural norms practiced and become informed on the role of ideology in storytelling traditions. Storytelling traditions include various branches of Literary Studies, including on the literary traditions of Indigenous communities, American Studies, Black Studies, Comparative Literature, English Studies, Ethnic Studies, and World literature. The combination of literary traditions in literary studies enhances learning experiences that both inform and challenge learners and educators alike to address themes associated with sustainability, like those proposed in the United Nations’ Sustainable Guide (UN's Guidelines). “The end of literary studies is a discussion of how literary writers use formal rhetorical devices to represent life, thereby giving us new ways to understand and experience our world…the end of literary studies is not, for example, the recognition that Milton used blank verse in Paradise Lost. The end of literary studies is a discussion of how Milton used blank verse in Paradise Lost to associate the Christian empire he represented with the English nation” (Aphorisms on Literary Studies). This approach to literary studies aims to enhance collaborative engagement by its coursework, lesson plans, and group projects that contribute to our viable futures.

The Gaia hypothesis is also known as the Gaia principle and Gaia Theory. The Gaia hypothesis realizes the life-giving forces of life on Earth, which dictate a worldview that is more ecologically sound and grounded like Indigenous thought. The concept that “Earth is a single organism” was popularized and accepted by modern scientists in the 1970s (Abou-Agag 2016) when British chemist James E. Lovelock and U.S. biologist Lynn Margulis coined the “Gaia Hypothesis” after the Greek Earth goddess (Britannica). They proved the importance of conceiving of things as a whole in science, a similar perspective known to Indigenous people like the Lakota, which Vine Deloria Jr. and Daniel Wildcat explain in Power and Place: Indian Education in America (2001). This principle is addressed by Deloria and Wildcat in their explanation of Indigenous metaphysics. Lakota philosophy also overlaps with recent understandings of the Gaia hypothesis. Again the ‘interconnectedness’ of the planet to sustain life is a worldview shared by many cultures, including the Lakota of the American plains region (Deloria). “With the entire Earth unified in this way, it seems artificial to distinguish between the parts that are obviously alive (the biota) and the inanimate oceans, rocks, and clouds. These inanimate parts are tightly coupled in chemical processes with the biota”(Abou-Agag 2016). In the 1970s Microbiologist Lynn Margulis and Chemist James Lovelock continues Goldsmith’s work on the Gaia hypothesis, as those who formulated this hypothesis and who “introduced into it the further complexity of the chemical reactions between the atmosphere and rock surfaces as they weathered (a process that bacteria can accelerate) and also the oceans full of algae.” The result was a chemical model of a complex interconnected chain of reactions whose ultimate effect was to regulate the conditions on Earth for the benefit of its life forms. “As Edward Goldsmith writes in The Way: An Ecological World-View, ‘What is required is a totally non-mechanistic theory of life and such a theory must by its very nature be holistic. Living things are alive because they are part of a whole.’ The main features of living things, those that make them alive – their dynamism, creativity, intelligence, purposiveness – are not apparent if one studies them in isolation from the hierarchy of natural systems of which they are a part" (qtd. in Sandner 2000).This model he called Gaia (Abou-Agag). For more information, visit OER Pressbooks on Classical Mythology & OER On Gaia by Harvard Edu.

Literary theory involves philosophy and schools of thought to understand literature. As a systematic account of the nature of literature, literary theory offers approaches to literature from a particular set of principles. These principles involve a “body of ideas and methods we use in the practice of reading literature. Not the meaning, but the theories that reveal what literature can mean'' (Literary Theory | Internet Encyclopedia of Philosophy). It is literary theory that gives us approaches on how authors and their texts relate – on the significance of class, gender, race, etc. – and from standpoints that include biographical information on an author and the text or on the linguistic and unintended aspects of a text. Hence, literary theory provides the ‘tools’ necessary to understand literature in depth. Literary theorists can trace the histories of texts to understand genre formations and to view literature as a collective, rather than as an individual cultural artifact. For example, Joni Adamson provides literary theory, cultural studies, and ethnic studies to offer ecocritical scholarship on Indigenous literature to address their sustainable storytelling traditions. Literary critics apply literary theory to a text or to a literary tradition. Literary critics rely on literary theory to understand literature. This relationship may cause some confusion between literary criticism and literary theory. Just remember that the purpose of literary theory is not to determine a causal sequence, but to engage in analyzing the corpus of an individual author or poet through a theory, like ecocriticism, feminism, or Marxism.

Coined by Kwane Ture (Stokely Carmichael) and Charles V. Hamilton in their work in 1967 on racism in the United States. Their book Black Power (1967) shows the intersection between isolated racism and institutional racism.

Animal studies inquire about epistemology through the social constructs of animals in literature. Many argue that epistemological knowledge formations are limited by over-determinations and partialities of our “species-being” (Gattungswesen), the human. Ecocritics since Leo Marx 1964 seminal work examine and rethink assumptions about who the known subject can be, so that the place of literature can be radically reframed in a larger universe of communication, response, and exchange, which now includes a manifold other species. For more information, visit Wolf 2009 on Animal Studies.