Chapter Six: On Arabian Nights & Gender Equality Intersections

Outcomes and Skills Practiced

- Familiarity with story collections, a form of Near East literature with medieval

- Textual analysis of frame and embedded narratives found throughout the Arabian Nights

- Identifying theme and its role in several embedded stories, especially on gender equality

- Critical writing exercises enhance close reading, analysis, and ‘ecocritical’ approaches.

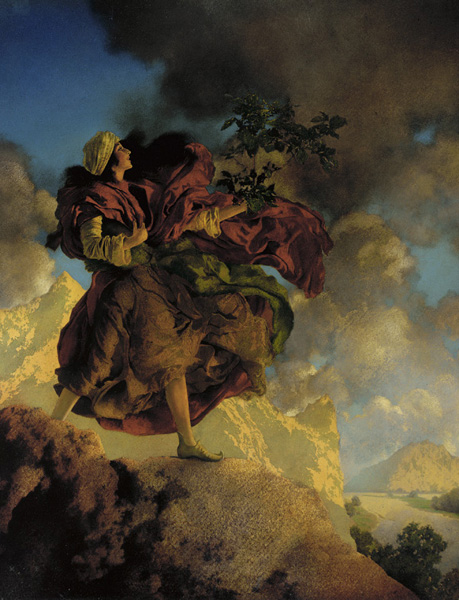

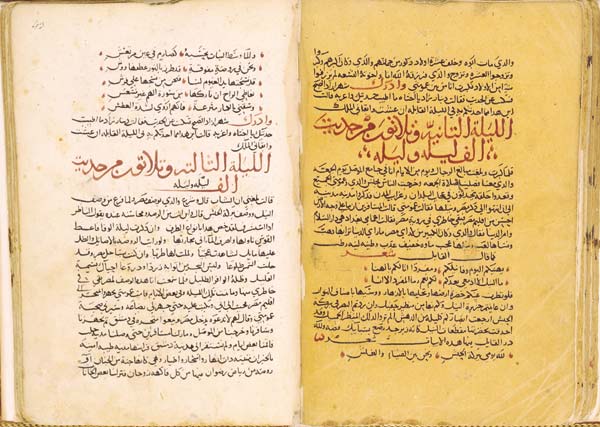

1915 Parrish’s art (left), 1220 1001 Nights storyteller, (center), 1300s Oldest Manuscript, & 1915 Bird Tells Truth (right) CC

Introduction to Chapter Six

One Thousand and One Nights is the world’s most well-known collection of stories. Current Persian and Arabic scholars recognize the literary merits of this tome of popular stories, poems, and songs “as a narrative, cultural, and historical document” (Seale 2021) of collected fantastic and wondrous stories. As embedded fables, these imaginative fables are framed by Shahrazad, its principal female storyteller.

As a whole collection, One Thousand and One Nights is culturally diverse with origins from oral traditions that come together in an intertext of stories. Traditionally, there is no one version alike.

…the hybrid character of the Nights, many of whose tales belong to a complex web of tradition. This web extends from the Buddhist Far East to the Christian West, and draws on a large variety of traditions, including (Buddhist) Indian, (Zoroastrian) Persian, (Muslim) Arabic and Jewish narrative traditions. In this way, the Nights both originate from a multiplicity of origins and in turn have passed on their legacy to a large variety of narratives worldwide. (Marzolph 6)

Recent studies highlight the collection’s origins and influences from ancient India, African city states, and China. Many tales in this story collection represent medieval Arabic literature that blend pre-Islamic tales with popular urban stories for entertainment. Scholars today translate the Nights to recover its Eastern legacies and undo misrepresentations like translations from Western orientalism. These efforts inspire 21st century readers with inquiries about the role of storytelling and the role of readers and interpreters.

Among Victorian translators, there was an underlying perception of the Nights as the domain of the explorer, adventurer, and anthropologist, and its content was treated as evidence of particular Islamic virtues or as heroic tales to be rendered with appropriate masculine vigor. Despite the fact that the sprawling Arabic story collection contains numerous formidable female characters, Victorian translators routinely cut or undercut tales featuring women or female characters. (Seale lxiii)

One Thousand and One Nights also represents the dynamic trade routes and the urban coffeehouse surrounding Baghdad, as well as Cairo’s storytelling cultures dating back centuries. In the West, the fantastic stories from the Nights greatly influenced European literature, especially after the 1702 French translation, which is based on the 1300s manuscript and new stories by a Syrian storyteller.

Published as The Arabian Nights, this version of One Thousand and One Nights includes new stories by Hanna Diyab, a Syrian storyteller. He retold unknown stories like Aladdin and Sinbad the Sailor. Since 1702, new European editions and translations of the Nights have influenced the imaginative works of Voltaire, Dickens, Charlotte Brontë to James Joyce and Edgar Allan Poe to Jorgen Luis Borges and Wole Soyinka, to name a few.

On the Legacy of 1001 Night among other Well-Known Story Collections

The earliest known Arabic manuscript of 1001 Nights dates back to the 1300s, at a time when Eastern knowledge thrived throughout the Islamic world.

“Arabic became an essential language for human knowledge in the medieval centuries during the bright period of the Islamic civilization, when Muslim scholars vastly contributed to knowledge and science in many fields: algebra, geography, medicine, social sciences, astronomy and many more” (OER Pressbooks on Arabic Culture & Language).

The way that the Arabian Nights traveled throughout Asia, the Middle East, and North Africa to medieval Europe, and was finally translated into French by 1702, was initiated with the founding of Baghdad, where, “One of the first libraries in the world was created by Assyrian king Ashurbanipal” (Puchner 108). Our modern-day access to this compilation of stories is demonstrated by an inclusive dynamic definition of ‘culture’. For example, the editor and translator of a recent 2021 publication of 1001 Nights show concerted efforts to include numerous cultures, whose members have contributed to this story collection. Dr. Martin Puchner underscores such inclusive collaborations that participated in the story collection of 1001 Nights and later the French translation titled Arabian Nights:

Translation was an act of homage on the part of the new Arab rulers, but it was also a canny move that allowed them to tap into the cultural resources of the conquered region. Soon, translations from Persian became the building blocks for new Arabic literature, above all, One Thousand and One Nights, which would eclipse its much smaller Persian antecedent and become a classic of world literature. Along the way, it immortalized al-Ma’mun’s father, Harun al-Rashid, who appears in many of the stories that are set in Baghdad. (Puchner 2023)

Prior to the first European translation by Antonio Galland in 1702, medieval Europeans also knew about the stories – as witnessed by the frame narratives in the works by Boccaccio and Chaucer. Renaissance dramatists William Shakespeare, Ben Jonson, and Miguel de Cervantes also allude to the Nights.

English literary historians claim that from Samuel Johnson through Dickens, ‘hardly a writer of note’ failed to ‘hint at, or mention, somewhere or other, the recollected pleasure of reading the Nights in childhood.’ Indeed, by the early nineteenth century, the inspirational presence of the stories of the Arabian Nights became itself a standard literary trope. (Seale 2021)

On the One Thousand and One Nights as Europe’s the Arabian Nights

Before the 1702 French translation of the Nights, its stories that traveled through North and West Africa and the Middle East reached Europe and influenced the story compilations of Boccaccio and later Chaucer, especially in their own use of a frame narrative. Boccaccio and Chaucer seem attracted to these stories, possibly because of their mostly non-religious content and alternative representations of gender, unlike the misogynistic morals of the medieval romance, a common theme that feminist Christine de Pizan addresses directly in the late 1300s and early 1400s.

In these stories, the usual religious themes are conspicuously absent, with the authors using magic to explain how the husbands discover the trysts. By omitting the divisive religious element, the Nights’ original story takes on a neutral element, allowing Chaucer to appropriate it for the moral, rather than religious, goal. This moral, which is present in many of the stories derived from the Nights, is “there is no such thing as a faithful woman. (Irwin 99)

Overall, the collection absorbed oral storytelling traditions that spanned from the 900s to 1300s C.E. with an array of genres from fantastic voyages to trickster tales and from heroic epics to animal fables and devotional literature to urban mysteries and horror stories about ghouls and flesh-eating female figures. “The Arabian Nights today offers readers a bewildering array of tale genres that foreshadow all the styles that define storytelling today – suspense, horror, crime, fantasy, adventure, romance’ (Horta xxi). Throughout the years, poetry was inserted that reflects classical verse in Arabic, of about 1,420 poems. The poems address love, grief, beauty, folk wisdom, and some help to advance the plot of a tale.

On the Story Cycle and Embedded Narrative

Most of us in the West may know the collection of stories as the Arabian Nights. This means it has been brought down to us from older Arabic texts known in the East as One Thousand and One Nights to Europe and translated as The Arabian Nights. Since the 800s C.E,, the stories affiliated with the Nights have one definite feature in common – its frame narrative and a few early story cycles of aja’ib – tales of marvels, wonders and astonishing things, including:

- “The Merchant and the Jinni,”

- “The Fisherman and the Jinni,”

- “The Porter and the Three Women of Baghdad,”

- “The Hunchback,”

- “The Three Apples.”

These stories are stories within stories that are part of the frame narrative. Their characterizations echo back to King Shahriyár and Shahrazad in the frame narrative and serve as exemplary tales. “These techniques of embedding narrative made it easy to incorporate new stories that employed similar themes, plots, motifs, or character types as the collection was remade by new storytellers and editors”(xxiii). One motif is its representation of magic.

In secular storytelling – like folklore – in place of the gods that actively manipulate the plot and outcomes, the role of ‘magic’ is emphasized. For example, to highlight characters on higher moral ground, magic plays the role of the leveler. Stories that rely on magic are widely integrated in popular literary traditions. Today’s Marvel Comics and its film adaptations come to mind, and the 2023 film release Dungeons and Dragons: Honor Among Thieves. Characters transform to represent the common good through magic.

What are Examples of Frame Narratives?

An earlier known collection of stories with stories within a frame narrative is the ancient Indian collection Panchatantra. It may have influenced the frame narrative of the Thousand and One Nights. By the 800s C.E., this collection was translated into Arabic. The stories represent different cultures throughout the Middle East, including Cairo, Egypt where “stories of Shahrazad were circulating in Arabic under the title Alf Layla wa-Layla, or One Thousand and One Nights.

The central story of Thousand and One Nights is a frame narrative about two brothers who ruled India and China. The frame narrative begins with their discovery of the infidelity of each other’s wives. In response, King Shahriyár, who is the most powerful of the two brothers, goes on a quest to avenge their injustices on every woman he marries. He decides to kill a new wife the morning after their wedding night. His kingdom endures Shahriyár’s indiscriminate vengeance. Then Shahrazad, the daughter of a trusted vizier of the king, tells her father that she will volunteer to visit King Shahryár in order to dissuade him from murdering more women. This initiates her role as the principle storyteller of the frame narrative. Incidentally, a French publication of the Nights has King Shahyiyár renounce his murderous claims at the end of the collection of stories. One interpretative phenomenon known as orientalism is traced back to Gallant’s 1702 French translation of the Nights. Misrepresentations of the East coincided with European colonialism and British imperialism.

The 2011 current Broadway production of Disney’s 1992 film Aladdin shows our continued enthusiasm for the Nights to this day. Director George Miller’s 2022 film Three Thousand Years of Longing features the struggles of a jinn to gain and hold onto his own liberty, which is the heart of its theme – forms of social injustices and the problematics of political power.

The ‘retelling’ of its stories across ages, continents, oceans, languages, and time since it was first known in 800 C.E. Akkad also emphasizes an approach to literary studies for students of literature; retold versions are part of the legacy and culture that has allowed One Thousand and One Nights to continue in one form or another.

One might study syntax and structure and use of language and all manner of literary devices, but this is one thing, this magnetic thing, when it happens, is a distillation of all that is joyful about storytelling. Anyone who as a child stayed up past bedtime with a flashlight and a paperback under the covers, anyone who’s ever sat by the campfire waiting on the climax of a good ghost story, anyone who has been made to momentarily cast the real world lose in favor of a fictional one knows this feeling intimately (xv).

The childhood memory of romantic poet Samuel Taylor Coleridge also shows us the profound impact Arabian Nights has had for European romantic writers. In one of his letters, Coleridge tells of his intrigue reading the stories that kept him up all night.

“I would seize it, carry it by the wall and bask and read. My father found out the effect which these books had produced – and burnt them.”

Scholars have noted that since the 1702 translation of the Arabian Nights, its tales of wonder and the imagination has made – and continues to have – an impact as a new form of storytelling that is unconventional and frees itself from any confines like religious doctrines or official political norms.

“In an age that increasingly placed values of science above the power of the imagination, the tales of the Nights liberated writers from the constraints of plausibility” (Horta xlii).

On the frame and embedded tales of One Thousand and One Nights

In the frame narrative of One Thousand and One Nights, Shahrazad tells a story every night to enchant and deter King Shahryár, who threatens her life and the lives of the young women throughout the kingdom. The King’s pledge of retributive justice follows his wife’s infidelity. The stories Shahrazad tells overlap, with stories within stories. And, several of them address the dynamics between people who are limited by their own short-sighted emotional state of mind, which clouds better judgment. A few of these embedded fables allude to the situation Shahrazad faces in its frame narrative.

The tale “The Story of the Fisherman and the Jinn” is told by Shahrazad. She presents a fisherman who innocently liberates a jinn who cannot contain his own anger toward anyone due to his imprisonment.

But presently there came forth from the jar a smoke which spired heavenward into ether (whereat he again marveled with mighty marvel), and which trailed along earth’s surface till presently, having reached its full height, the thick vapor condensed, and became an Ifrit huge of bulk, whose crest touched the clouds while his feet were on the ground. His head was as a dome, his hands like pitchforks, his legs long as masts, and his mouth big as a cave. His teeth were like large stones, his nostrils ewers, his eyes two lamps, and his look was fierce and lowering. OER Pressbooks on “1001 Nights”

In this story a fisherman sets a jinn free only to experience the jinn’s wrath. The angry jinn suffered imprisonment and has vowed to kill anyone who releases him.

“Ask of me only what mode of death thou wilt die, and by what manner of slaughter shall I slay thee.” Rejoined the Fisherman, “What is my crime and wherefore such retribution?”

Since the jinn refuses mercy, the Fisherman resolves to outsmart him through cunning — the telling of a tale. The Fisherman’s tale ends by thematically circling back to Shahrazad when he shows the jinn honored and rewarded acts of mercy. The conflict between King Shahryar and Shahrazad of the frame narrative is alluded to by the Fisherman’s embedded narrative. Like the jinn, the King also confuses acts of kindness with injustices.

In anticipation to hear how the story ends, King Shahryár allows Shahrazad to tell her tale the following night. Throughout the One Thousand and One Nights, tyrannous figures are repeatedly shown alternatives to short-sighted fits of anger that have the potential to lead to acts of violence.

On Orientalism and its Prevalence in the Arabian Nights?

According to Palestinian postcolonial scholar Edward Said in Orientalism (1978), since early European colonialism in the East, representations and understandings of its people reflect Western fears of what is seen as ‘foreign’ while they enforced efforts to dominate the East. He argues that orientalism was a “Western style for dominating, restructuring, and having authority over the Orient” (Harlow, Carter 1999). We can go to literary works – including adaptations in animation – to witness and learn about this colonial phenomenon, and a practice that leads to misrepresenting the cultures of the East and resembles Western ideological trends of ‘othering’ social groups and nature.

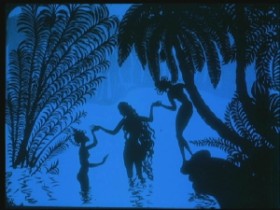

Coincidently, the oldest surviving feature film in animation is also an adaptation of The Arabian Nights. The 1926 German film The Adventures of Prince Achmed by Lotte Reiniger represents motifs from Aladdin through European expressions of orientalism.

For example, witness how the stills from the film misrepresent ‘orientalize’ – the East. View a still from Reiniger’s 1926 film below. Then, try to identify characteristics in a still image that either limit an understanding of Eastern cultural norms or simply reduce them to stereotypes through caricature characterizations. OER “The Adventures of Prince Achmed”

Pari Banu (left), title card, and two more silhouette stills, Lotte Reinger’s 1926 silent film The Adventures of Prince Achmed CC

The characterization of Eastern peoples are figures in shadows in black with a solid blue, orange, and yellow background. The silhouettes illustrate clothing associated with cultures of the East – characters with featured turbans which identify male figures. Their postures tell a story of how they dance and engage in a sort of ‘harem’ indoors, as the females remain in shadows (see still with orange background). This one example demonstrates visions of orientalism that became the ‘norm’ in the motion picture industry – stereotypes such as the male figures living in excess and leisure.

Edward Said’s postmodern interpretive theory of orientalism challenges us to identify such constructions and to avoid blatant, disingenuous misrepresentations. This line of analysis also supports our learning of more representational depictions in an effort to minimize cultural biases and uphold the rich and vast culture of The Arabian Nights. Ultimately what scholars of orientalism demonstrate by these expressions of the West misrepresenting the East are examples of popular construction that perpetuate racialized constructions in film.

As noted earlier, the West has absorbed the storytelling cultures of the East, like The One Thousand and One Nights through a 1702 French-language publication titled The Arabian Nights. Hence, the West absorbs the cultural norms of the East while paradoxically treating these cultures as ‘other’ or inferior. These sorts of paradoxes are rich in meaning and worthy of a literary study to explore new ways to value literature without dishonoring the culturally rich and storytelling traditions of its origins and cultures. Additionally, ecocriticism of orientalism reveals themes that pertain to sustainability.

How does the Arabian Nights Address Sustainability?

An interpretation of how the West responded to Eastern literature may offer us insights on what Nigerian writer Chimamanda Ngozi Adichie addresses in The Dangers of a Single Story, on the importance of authoring our own experiences, which contribute toward identity affirmation. For example in Vanity Fair (1848) by William Thackery, the protagonist as a boy would lie for hours under a tree with “his favorite copy” of The Arabian Nights. Its stories of adventure and imagined experiences act as an environment to avoid the rules imposed by adults.

Examples like this one tell us that those “attracted to these elements of the fantastic” in The Arabian Nights reveal European “issues of political oppression” (Seale 2021). The United Nations Sustainable Development Guidelines include topics on gender equality and justice (UNSDG Toolkit, Pressbooks). And, coincidently, themes on oppression are fundamental in The One Thousand and One Nights, expressed through frame narrative.

Key Points

- One Thousand and One Nights is an example of a folkloric story collection

- The history and collection of 1001 Nights is an example of intertext

- A literary device that ties many the tales in 1001 Nights is the frame narrative

- The embedded tales throughout 1001 Nights show its rich and complex scale

- Western translations and cinematic adaptations of 1001 Nights are examples of orientalism

- Ecocriticism reveals orientalism throughout The Nights

Media Attributions

- Princess Parizade Singing Tree © Wikipedia is licensed under a CC0 (Creative Commons Zero) license

- Arabian Nights Manuscript © Wikipedia is licensed under a CC0 (Creative Commons Zero) license

- The Talking Bird © Wikipedia is licensed under a Public Domain license

- Flying Woman © Canadian Museum of History is licensed under a CC BY-NC-SA (Attribution NonCommercial ShareAlike) license

- Lotte Reinger’s 1926 Silent Film © Wikipedia is licensed under a Public Domain license

Any imagined world, place, or character that operates as ‘real’ in a text, yet challenges the readers’ own perceptions of reality is considered fantastic. In folklore, the fantastic is a mode in the fable, legend, and fairy tale. The fantastic is also in more recent literary forms – like the gothic and science fiction. The fantastic, as a mode of imagined elements in works of art, film, and literature, subsumes philosophy because these elements provide imagined perceptions that challenge traditional ways readers understand and describe ‘reality’. Hence, fantastical elements may contribute to transforming one’s own traditional beliefs and worldviews. Audiences may experience what Romantic poet William Coleridge calls a ‘suspension of disbelief’.

Coleridge agrees that non-mechanistic thinking better expresses the actual, apprehended in wonder, the imagination unbound; and he proposes fantastic literature is an excellent medium for activating wonder, and so actualizing the phenomenal world which may have become estranged from us simply through the ‘film of familiarity’...The human imagination at creative play in literature and the actual experience of the presence of the non-human universe connect through the ideal and the emotional.” (Sandner 2000)

Since the early modern era, the fantastic is closely associated with the emotions of its characters – as in the gothic and Romantic poetry or their modern or postmodern sensibilities, witnessed throughout European, Southern, Latin American and African-American literature, like Franz Kafka’s The Metamorphosis (1915), William Faulkner’s As I Lay Dying (1930), Gabriel Garcia Márquez’s Cien años de soledad (1967), and Toni Morrison’s novel Beloved (1992). This means that there are similar elements between the fantastic, magic realism, and the supernatural.

…regarding the supernatural elements, I have to agree with the critics that link this novel [Beloved] to the tradition of South American magical realism. Why? Basically because the characters treat the fantastic only as another part of life; rather than questioning its existence, they embrace it or deal with it. OER Pressbooks

The fable is one example of a literary form of folklore, like the animal fable. The fable is witnessed in Aesop’s Fables from 600 B.C.E and other examples include those from India and the Middle East. Fables and the animal fable in particular can help us to conduct ‘ecocritical’ readings. Like the fairy tales and Arabian Nights, readers may experience and explore the non-human in the fable.

Oral tradition involves performing somatic and linguistic cultural codes as a dynamic visual art. These performances involve dancers dressed in sacred clothing with symbolic significances, along with music and dynamic jestering. A social group’s oral tradition is maintained and related through memory and referential communication to make meaning. Social groups communicate their people’s legacies of known institutions for the present generations to learn from and preserve. Oral tradition as performance addresses known understandings of astronomical, cosmic phenomena, biology of fauna and flora, especially about their medicinal and nutritional properties, refer to geographic locations and seasonal phenomena, relate political history and treaties, reflect on philosophical and religious storytelling traditions, and perform rituals on current technologies. Scholars like John Miles Foley point out that once an orally delivered text is written down, its original version has been “reduced,” of a once-living experience to one of bureaucracy, forever eliminating much of its meaning. Oral traditions dwarf written literature in both size and diversity (Foley Native American Oral Traditions).

A collection of stories with many contributors, Aesop’s Fables and Arabian Nights are two examples of an intertext. Intertexts in our times refer to building an understanding of a topic in one text by also working with several other related texts. Intertextuality is considered to mean the shaping of meaning that also relies on multiple and related texts, like the series of stories found in the New Testament, for example.

Historically, Orientalism is associated with a discipline in the Euro-American academy that was established in 1784 by the father of comparative literature, Sir William Jones, who asked “how the British might rule India” (Harlow, Carter 1999)? As a concept and literary theory, Edward Said coined the term and created the literary field of Postcolonial Studies. In his 1978 book, Orientalism, Said investigates instances of the West’s views of the East by arguing that Orientalism was a “Western style for dominating, restructuring, and having authority over the Orient” (Harlow, Carter 1999). Said argues that this phenomenon is both a theory and a practice that constructs images of the Orient or the East from the perspective and prejudices of the West through exoticism and feminized personas as weak, in order to contrast the East with Western views of itself as rational, masculine, and powerful. The concept and theory of Orientalism looks into constructions of the ‘other,’ as seen in how the African people are portrayed in Heart of Darkness (1899). In his novella, Conrad’s literary technique instills readers to respond to the forms of racism practiced throughout European colonialism. In ecocriticism, the American landscape is also studied as an example of ‘orientalism’, since it has also been imagined and colonized by similar prejudices and practices: “I am suggesting that the American literary environmentalism be approached as a form of domestic Orientalism…[for having authority] over the real territories and lives that the environment displaces and for which it is involved as a representation” (Mazel qtd. in The Ecocritical Reader). For more information on literary theory, visit OER Literary Theory.

Scholars and researchers of Arabian Nights view this collection as encompassing all aspects of storytelling – genres, the supernatural, ghouls, the jinn, and more. Part of the global canon of fantastic literature, Arabian Nights is also known by its Arabic title 1001 Nights, which is the most influential book in all of world literature. As a transcontinental collection of stories from Persia, India, and the Middle East, the series of parables and embedded fables in the 1001 Nights are narrated by commoners rather than by monks or rulers. Its tales reflect multiple styles and forms including the fantastic, horror, and the detective about on sex and death, treachery and vengeance, magic, humor, and wit with happy endings. A new 2021 English publication by translator Yasmine Seale “embraces [the] Orientalism that was stripped out in previous French translations,” which mistranslated its stories as ‘fairy tales’ for children instead of adults. Another example is the Grimm Brothers’ whose tales exorcised themes on incest and violence for modern audiences. Critics make this point by arguing Western folk traditions are rife with misinterpretations – like believing that Peter Pan was meant to become a man. Recent work on Arabian Nights highlights how it has inspired authors including William Shakespeare, Miguel Cervantes, Charles Dickens, Edgar Allan Poe, Naguib Mahfouz, Neil Gaiman, and many more. The diaphanous tradition of the Arabian Nights reflects its close marriage to oral tradition through its legacies of storytelling performances in coffee houses that existed over four hundred years ago in Cairo, Egypt. Many of its stories reflect a ‘literary theory of enchantment,’ where we can cast out the real world for a fictional one. Its frame-narrative is led by Shahrazad, a young woman who tells stories to avoid becoming another avenged victim by a psychopathic sultan leader. Its frame-narrative may have inspired Boccaccio and Chaucer. Western cinematic, comic, and popular culture adaptations continue to ‘Orientalize’ the Arabian Nights as demonstrated by Disney’s Aladdin.

The theme of a narrative or a play is the general idea or underlying message that the writer wants to expose. In Elizabethan Theater, “John Milton states as explicit theme of Paradise Lost to 'assert Eternal Providence,/And justify the ways of God to men.' Some critics have claimed that all nontrivial works of literature, including lyrical poems, involve an implicit theme which is embodied and dramatizes in the evolving meanings and imagery” (OER Elizabethan Theater). Whether you define it as the overarching subject matter of a text or its message, identifying themes in literary studies establishes initial skills in describing, summarizing, and offering a commentary to a piece of literature, without additional theoretical approaches. Yet, some research is helpful - of its historical era, culture, and geographic region.

Witnessed in One Thousand and One Nights, this is a story within a story. Shakespeare’s Hamlet has a play performed in the play, an embedded drama, and also his comedy The Taming of the Shrew (1591) features a play-within-a-play.

A concept that encompasses the dynamic and intricate network of how humanity affects communities, the environment, and climate. Current efforts to address a wide array of cultural and sociological practices that are all interrelated and connected to seriously address the causes and effects of ‘climate instability’ and other injustices that plague some societies while threatening the rest. The United Nations offers 17 goals of development to highlight many facets of society – from the production of goods and treatment of women and the impoverished and social justice and renewable energies (UNSDG ). Yet, current scholarship by ecocritics in literature emphasizes the fundamental need to address today’s crisis – a sustainable ideology, to demystify human and nonhuman binary thinking. Where we as a global people realize that we are interconnected to local and global ecologies. This worldview can also demystify current human tendencies of placing humanity above the nonhuman. An example of this argument is witnessed in Frank Boom’s ecocritical analysis of Ovid’s Metamorphosis, Book 10 and 11, on the mythological tales of “Orpheus and Cyparissus” (OER Article on Today's Climate Crisis & Ovid's "Metamorphoses").