Chapter Nine On Late Medieval European Revisionism & Gender Equality

Outcomes and Skills Practiced

- Chapter Nine builds on close reading and interpretive skills on the allegory

- Practice in textual analysis feature literary concepts like the dream vision and revisionism

- To succeed, select several assignments to continue to practice textual analysis of Pizan’s prose while you consider an ‘ecocritical’ approach to literary studies

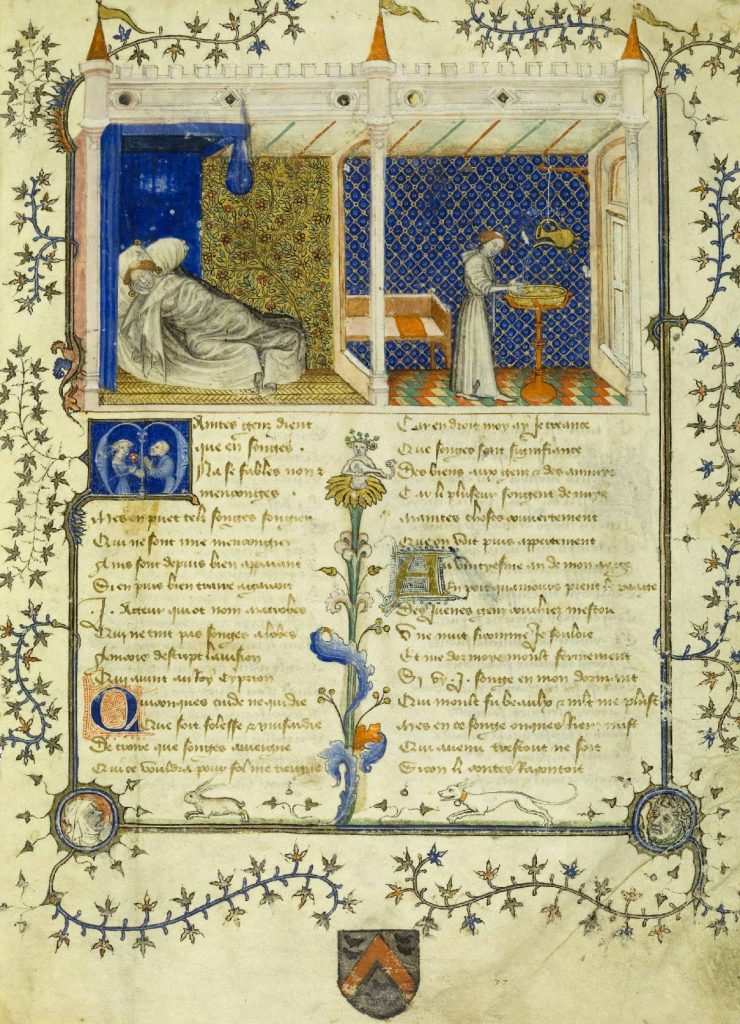

1414 Pizan’s Amazons assist Trojans (left), 1405 Pizan’s book Duke of True Love (center), & Joan of Arc, France 1450s CC

On the Biography and Literary Significance of Christine de Pizan

Scholars to this day point to her father as the key figure in Christine de Pizan’s life who secured her education. In the latter part of the 1300s, Christine de Pizan’s childhood was filled with intellectual opportunities, through her father John de Pizan’s patronages in Paris, France, which ensured access to private libraries and tutors. Her own husband Etienne du Castel also supported her intellectual pursuits. Christine de Pizan learned Latin, Greek, and Roman history and became an avid reader of classical literature and philosophy, including the works by Dante and Boethius. Like these thinkers, the work of Christine de Pizan also contributed to the European Renaissance, yet through a corpus of work that reflects a feminist Renaissance spirit.

“Christine (as many of us have shown) by no means simply paraphrased what she took from Boccacio, or from Boethius, or from Dante, or Ovid, or Bouvet or Augustine. We know she often transformed what she read into very original ideas of her own” (OER on Pizan).

Operating within the culture’s superstructure, Christine de Pizan has been recognized by medievalist literary scholars as a ‘proto-feminist’ and cultural revisionist.

After the death of her husband, Christine de Pizan lived on her own published work with the support of patrons in France while caring for three children and mother-in-law. Witnessed throughout her published work, she aims to revise social norms to reform within. Ninety-four-year-old Canadian American historian Zemon writes in the foreword of Pizan’s The Book of the City of Ladies,

“Christine argues that women and men were created equal by God, with the same potential in every sphere – and where they are different, women are higher and better” (Zemon, Davis xix).

Becoming both a writer and public figure, Pizan advocated for women and supported their public roles and access to engage in intellectual undertakings, including formal education. Pizan’s feminism is suggested by her support for women to choose their own paths – to integrate into mainstream patriarchal society and engage or to follow traditional roles like marriage and nunneries.

Themes in her work that confront medieval expressions of misogyny show Pizan’s wish to also revisit and revise European medieval literature to correct instances that misrepresent women. Public debates surrounding The Romance of the Rose are well known instances of Pizan’s efforts to counter misogynist sentiments throughout allegorical romances of her day.

She also counters European misogyny and sexism by publishing works that reclaim the contributions of women in European and Western culture in its literature, classical mythology, and Christian scripture. This is Pizan’s form of revisionism. In her poetic narratives and public debates, Pizan decenters the masculine entitlement of her day by illuminating the contribution of women in literature and religious doctrine throughout Western literature for over a millennium. She addresses many mythological and historical female figures, including the poetics of Sappho from 600 BCE and female biblical figures.

On Medieval Dream Visions, The Romance of the Rose & Pizan

The medieval dream vision is a form of literature where the author narrates the spiritual experiences set within a dream. As a framing device, dream visions relate inner spirituality in verse, as in the anonymous religious poem The Dream of the Rood (700s C.E.). The role of the dream as a framing device is to draw attention away from the vessel – the human body – and toward a deity. In medieval literature, the source of the dream is the Christian God.

For example, the opening lines of The Dream of the Rood evoke dreams as a source directly tied to a deity.

Lo! choicest of dreams I will relate,/What dream I dreamt in middle of night/When mortal men reposed in rest/…/Above on the shoulder-brace. All angels of God beheld it” (OER Pressbooks on Dream Visions).

Other examples of the framing device through a dream vision are medieval dream visions . These dream visions are autobiographical and direct accounts of one’s own spiritual awakenings.

For example, the dream visions of Christian mystics like Margery Kempe reveal forms of spiritual awakenings where God appears in a dream to test a devotee.

…on a time as she lay alone and her keepers were from her, our merciful Lord Christ Jesu, ever to be trusted (worshiped be his name) never forsaking his servant in time of need, appeared to his creature, which had forsaken him, in likeness of a man…(Pressbooks on Margery Kempe)

By the mid-1300s, the dream vision transformed from a Christian awakening framing device into a device for poetic narratives on chivalric love, in particular on the ‘lover’s complaint’ trope.

Guillaume de Lorris is a French poet who wrote The Romance of the Rose (1225), a seduction narrative poem that is framed by a dream vision. Its continuation in 1280 was written by Jean de Meun. This continuation adapts the source to include a seduction scene developed through allegory. Meun claims that he wanted to narrate “the whole art of love” in his continuation of Lorris’ romance. Yet, Meun represents a seduction scene through the lens of male dominance.

“This assault echoes not only paraclausithyron (complaint of the lover at his beloved’s door) of Ovid’s Amores (I.6; Hanning 2010: 110) and medieval lyric, but also the language of siege warfare and the tradition of psychomachia, where the body is sometimes represented as a walled enclosure” (#MeToo 3).

This representation reflects the male-centered social norms of masculine entitlement in medieval Europe. For example, Meun’s denouement has the Rose in the garden extracted by the male protagonist. Through allegory, his romance sanctions non-consenting sex by erasing the voice of the Rose in the seduction scene.

On Pizan’s Form of Feminism

Christine de Pizan challenges established Western literary norms of her time through her critique of works of literature like de Meun’s adaptation of de Lorris’ romance. In doing so, she both elevates women’s role in literature and centers women in discourses on morality, gender, and sexuality.

For example, through the ‘reinterpretations’ – revisions – throughout her writings, Pizan repeatedly addresses the elevated position of women:

“And what of those who say that the female body is weak and imperfect? If anything that body is more noble than man’s for Adam was created from the mud, while Eve was created from the body of man” (Zemon Davis xix).

Also, in the spirit of Ovid, Pizan’s revisions transform the literary landscape itself. She retells Medea’s injustice by Jason by rewriting Medea as “despondent” rather than turning against her own children, and she addresses the injustices of women in The Book of the City of Ladies (1405), The Duke of True Love (1405), among her epistolary works.

For example, in The Book of the City of Ladies (1405), Pizan confronts ‘misogynist writing’ by her own version of allegorical dream visions.

And the simple, noble ladies, following the example of suffering god commands, have cheerfully suffered the great attacks which, both in the spoken and the written word, have been wrongfully and sinfully perpetrated against women by men who all the while appealed to God for the right to do so.

Her own form of feminism not only gives voice to victimized women, but she also provides, through allegorical narratives, a methodology of prevention, of halting sexual violence, and ways to help women after they experience sexual violence, as she asserts in The Book of the City of Ladies:

She will restore harmony in Christendom and the Church.

She will destroy the unbelievers people talk about, and

the heretics and their vile ways, for this is the substance

of a prophecy that has been made…

Ultimately, Pizan challenged the literary trope of the lover’s complaint of the romance, which – by default, it seems – sanctioned rape through narratives of seduction and objectifying women. She argued that representations of the male lover’s right to conquer women led to actual violence against women outside of fiction. Through her literary works, Pizan gives voice to women and credits their intellectual talents. She confronts misogyny to halt literary misrepresentations of women to expose male moral hypocrisy and systemic misogyny.

On Emerging Paradoxes in Pizan’ work

To understand what current scholars deem as Pizan’s “conservative” value system, let’s witness how the corpus of her work represents a desire to fit within the system. Meaning, her prose addressed the society she belonged to and contributed to through her publications.

For example, when Pizan writes

“The wise housewife must know everything about her household, even about the preparation of food, so that she can direct and command her servants”

(The Book of the Three Virtues “Book Three”).

She reclaims domestic spaces for women as intellectuals and members of affluent families, a model of female virtue comparable to male dominance of their own spaces. Her work does not advocate revolution; rather, she argues for reforms of inclusive gender equality within standing institutions.

In Book II of The Book of the City of Ladies (1404), the narrator ponders which gender parents prefer to have, and asks Lady Rectitude,

“Are daughters more trouble than sons?”

The question is a valid one. The European version of the institution of marriage implicates the father, the male gendered head of the household every time one of his daughters marries because of the required dowry the father must have for his daughter’s future husband’s family, his future in-laws. In other cultures, the obligation of a dowry is of the husband to be and his family, who must offer a dowry to the family of the wife-to-be. He also must live with his wife’s family. Hence, the European institution of marriage aggravates gender neutrality since the bride must give wealth to the male head of the household of her husband-to-be, who are already affluent in wealth. It is the male of the household who can own property. European marriages are designed to sustain this gender biased institution.

Lady Rectitude’s answer reveals the character and quality of dominant society, whose male gendered members of society are those who manage all formal institutions, such as finances, education, and marriage. On the subject of affluent families, Pizan quotes Petrarch to argue that the logic of preferring boys is nonsensical. “Just see how many sons you can find who care for their father and mother.”

Lady Rectitude, because I understand and see clearly that women

are in the right against the things they are so often accused of,

please make me comprehend better the injustice of the accusers.

And again I cannot keep quiet …when women are pregnant

and give birth to a daughter, the husbands are unhappy.(Norton 141-142)

On this subject, Petrarch speaks the truth when he says, “Oh foolish man, you desire to have children, but you could not have a more mortal enemy: for if you are poor, they [children] will find you tedious and will desire your death to be rid of you; and if you are rich, they will desire it no less, in order to have what belongs to you” (143).

Pizan’s allusion to Petrarch follows European writing conventions as it adds a satirical tone to her narrator, and satire is reformative. Throughout Christine de Pizan’s work, she demonstrates her willingness and agility to engage in and confront contested topics, including medieval misogyny.

On the Romance of the Rose

The Romance of the Rose was written by Guillaume de Lorris in 1230 and continued by Jean de Meun in 1265. Lorris’ initial theme on the lover’s complaint was transformed by Meun. “Jean de Meun had set himself up in opposition to Guillaume de Lorris’s more graceful courtly narrative, peppering his text with debates about free will and determinism” (Walters 2017). The popularity of Romance of the Rose during Pizan’s life served as a platform for her to engage in debates about its misinterpretations of women and its theme on sanctioned violence.

“Christine de Pizan’s criticism of the Rose focused on its obscenity, its use of universalizing misogynist tropes, and its ambiguity…some of whom might uncritically accept or, worse, reproduce its violent portrayals of gendered relations” (Hult qtd. Holland 327).

Christine de Pizan’s justification for engaging in a ‘male-dominated’ social forum is through her religious devotion, which also guided her desire to reform society. “Christine later noted that her superior reasoning powers showed just what a “mere woman” like herself could do when she was “armed” with a correct understanding of the “doctrine of Holy Church” (Hicks qtd. in Waters).

For example, witness the female figures in the Romance of the Rose depicted in types.

In her hand she held a mirror.

A rich headband she did favour

Binding the tresses of her hair,

Tightly, her tresses fine and fair.

Her sleeves were tightly laced and she

Wore pure white gloves to keep

Her white hands from the burning sun.

This character is Lady Idleness who holds a mirror in leisure. Christine de Pizan objected to these representations that had the effect of sanctioning nonconsensual sex – a rape witnessed by the lover’s advances of the Rose.

For you cannot resist me, farther,

And I would have you know, beside,

You’ll gain naught from folly or pride.

Rather surrender yourself to me.

While American universities have offered works for consideration by male authors like Dante, Chaucer, and Boccaccio, the works by female authors, like Christine de Pizan in medieval Europe or Sor Juana de la Cruz in New Spain, have only recently been added to the canon.

In the late medieval period, there lived a woman named Christine de Pizan. She wrote a book called The Book of the City of Ladies. This was a book about women. It was a book about all the amazing things women brought into the world…In building this City of Ladies, she created a refuge for women to flock to in the future during a time when the world was dangerous for women (Aurora Brown 2021).

Christin de Pizan destabilized the canonical works of her day through her engagement in public epistolary debates against misogynist books and her own rewriting of popular forms like dream visions. She addressed Western literary tradition and its misogynistic tropes like the lover’s complaint to expose the silencing of female rape victims or careless yet threatening appeals to nonconsensual sex in popular literature. She also wrote, edited, and published allegorical retellings to correct misrepresentations of women in canonical Western literature, like The Book of the City of Ladies (1405). Her work is an example of late medieval and early modern feminism in Western literature (Richards 1998) OER on Pizan and her work.

On Christine de Pizan’s Allegories Centering Women and Morality

Initially, Christine de Pizan wrote poems about her private life, and then soon wrote to address public discourses and debates. Her literary works in the late 1300s and early 1400s paralleled an era in European literature that misrepresented women. As a millennial writer, Pizan’s work can also be understood as both innovative and revisionist.

This opened opportunities for a new generation of writers to emerge and fill the imagination with themes closer to home; like outbursts of a plague and the Hundred Years’ War of warring kingdoms nearby, among others.

The literary works of Christine de Pizan elevate women’s intellect and moral integrity. Pizan presented innovative mythological allegories to revise and replace existing popular medieval literary works, including works known as the dream vision. Traditionally, medieval dream visions negatively represented women in works that emulated misogynist views.

On Pizan and Emerging Trans-Female & Trans-Male Identities

In The Book of the City of Ladies (1404), the main character changes gender, from female to male, a transformation of a transgender identity that contrasts with both classical homoeroticism and Ovid’s attention to the ‘gender neutral’ Iphis. Ovid’s Iphis, regardless of her androgynous physical traits and name, fails to embrace an ‘imposed’ male identity, as witnessed by Iphis’ rejection of amorous desires or marriage with another female. “The two loved and longed for each other, but Iphis was filled with doubt. Ianthe thought Iphis was a boy, and Iphis believed lust between two women was immoral” (WordPress on Ovid’s “Iphis,” from Book IX of “Metamorphoses”).

Yet, in Pizan’s allegory, the new identity is not questioned, but embraced – perhaps due to the fact that the character wishes to change their own gender.

And my appearance was changed and strengthened,/And my voice become deeper,/And my body, harder and more agile./But the ring that Hymen had given me/Fell from my finger,/Which troubled me, as indeed it should For I loved it dearly. / Now I will prove that I became a real man.

From this perspective, her feminism is cultural work as an activist and reformer through literature. Her works show a methodology to revise and reform through her version of feminism.

On the #MeToo Movement’s Dialectic and Sustainability

One rationale as to why the work of Christine de Pizan is not taught in university courses, including in Gender Studies and LGBTQ+ Studies classes, historians argue, may be due to her choice to reform within the current social order, in place of advocating for revolutionary change. And perhaps, another related reason lies in how Pizan’s work is seen by critics as supporting the status quo too conservatively, which places women of different socioeconomic status and people of various genders and religious doctrines in an unequal disadvantage. Recent #MeToo criticism on Pizan addresses past efforts that have understood her work as ‘ambivalent’ (Holland and Hewett).

“Christine’s views as ‘ideologically ambivalent’, almost conservative…Because critics have often taken Christine for conservative, feminists have sometimes hesitated to cite her (Richards 1998).”

Yet, recent literary work inspired by the #MeToo movement has renewed the gestalt against misogyny – similar to Pizan’s critiques of misogyny in her time, especially on subject matters concerning rape, which elevates her feminism then and now.

“Christine de Pizan’s narratives of rape prevention and retribution revise the social rape ‘scripts’ that focus on women’s essential vulnerability (#MeToo and Literary Studies 328).”

In light of the #MeToo Movement, perhaps Pizan’s limitations also reflect that she ‘reformed’ and ‘revised’ within her present-day superstructure: Christianity, politics, and social society.

On the work of Pizan and Ecocriticism

A fruitful and provocative topic for projects on ecocritical understandings of Christine de Pizan is misogyny. While her rhetorical debates on the Romance of the Rose and her own work address misogyny as a cultural norm and systemic injustice, medieval literature also offers opportunities to further explore. For example, one of the themes of the UNSDG is peacemaking, and romance is a literary form that concerns itself with the conflict of the crusades in legends, dream visions, and epistolary literature.

One main concern for Pizan and today’s feminists is the way literary works like the Romance of the Rose equated the conquering of women to warfare. During Pizan’s lifetime the Hundred Years’ War between England and France occupied the imaginations of her generation, which culminated in Pizan’s poem on Joan of Arc – its heroine was Christian, of rural Western France, and captured by the English. William Shakespeare places Joan of Arc’s fate on stage in Henry the VI, Part 1 (1597).

Gender inequality, misogyny, and warfare are interconnected in the literature of Pizan’s day, implying that systemic dependence on war is represented through gendering human desire – through the transition from ‘normal’ sexuality to heterosexuality. Intersections between topics on gender inequality and perpetual exploitation of natural resources by warfare offer ecocritical understandings of the emergence of heterosexuality as the dominant form of sexuality and war.

The following and last chapter of this book also addresses systemic gender inequality, along with heterosexual marriages that are not only unwanted by the spouses but ironically represent forms of punishment. Not even the play’s heroine Isabella – who resides in a nunnery – escapes a marriage proposal in Shakespeare’s ‘problem play’ Measure for Measure (1603).

Chrstine de Pizan lived during the middle ages in France although she was born in the region of Florence in 1364. She is the first woman to become a professional writer in Europe and her literary production reflects an exegesis of the misrepresentation of women in classical and medieval literature. She wrote allegories in prose and verse and didactic treatises. Christine de Pizan’s revisionist narratives and poems uplift the status of female figures in the Western canon in the Book of the City of Ladies (1405) and The Book of the Duke and the True Lovers (1405). She reclaims Christian morality through her female allegorical figures, as her form of feminism at a time when the concept is not yet officially recognized. Pizan also critiqued Roman writer Ovid’s limitations of representing women and contemporary writers, like satirist Jean de Meun’s. He wrote the second part of The Romance of the Rose, a well-known popular medieval ‘lover’s complaint’ in European literature. Meun’s allegory represents women through misogynist characterizations that erase both their voices and humanity and themes on ‘conquering love’. Additional sources: OER on Christine de Pizan & Rhetoric

Key Points

- Featured biography & history of Christine de Pizan within context of early 1400s France

- Emphasis on Pizan’s role in Late Middle Ages as a proto-feminist

- The literary trope of gender equality throughout Pizan’s work affirms role of women

- Pizan’s revisionist allegorical dream visions offer literary spaces on rape prevention

- Gender fluidity intersects with representations of nature in Pizan’s work

Media Attributions

- Queen Penthesilea Harley © Wikipedia is licensed under a CC0 (Creative Commons Zero) license

- Book of the Duke of true_lovers © Wikipedia is licensed under a CC0 (Creative Commons Zero) license

- Joan of Arc © Wikipedia is licensed under a CC0 (Creative Commons Zero) license

- Le Roman de la Rose

Feminism explores the representation of sex and gender identities to learn how they challenge expectations, social norms, and expressions of oppressive power dynamics. Feminist criticism also explores the representation of women to build on Gender and Queers Studies, as a part of feminism as an interpretative method. For more information, visit (OER Pressbooks).

The theme of a narrative or a play is the general idea or underlying message that the writer wants to expose. In Elizabethan Theater, “John Milton states as explicit theme of Paradise Lost to 'assert Eternal Providence,/And justify the ways of God to men.' Some critics have claimed that all nontrivial works of literature, including lyrical poems, involve an implicit theme which is embodied and dramatizes in the evolving meanings and imagery” (OER Elizabethan Theater). Whether you define it as the overarching subject matter of a text or its message, identifying themes in literary studies establishes initial skills in describing, summarizing, and offering a commentary to a piece of literature, without additional theoretical approaches. Yet, some research is helpful - of its historical era, culture, and geographic region.

Misogyny is a cultural sentiment and social norm witnessed in Western cultures whereby social constructions of the feminine reflect treating anything associated with the female as inherently inferior and with a degree of hostility that culminates toward ‘hatred’ and even justified violence. The work of Christine de Pizan and scholarship on global rape culture through movements like #MeToo investigate misogyny. Contemporary studies on misogyny also offer a methodology to support present victims, to demystify victimhood, and to empower women as rape prevention by “discourses of survival“ (Torres, McNamara qtd. Holland, Hewett 328).

A poem, narrative, or other types of texts like art and film with symbolic significance is allegory. The whole narrative of allegorical poetry, for example, – its storyline, characters, and setting – is not to be understood literally, but symbolically, especially of characters as personification. Famous allegories include Aesop’s Fables and John Bunyan’s The Pilgrim’s Progress (1678). The allegory is not to be confused with the satire, like George Orwell’s Animal Farm (1945). The symbolism of an allegorical story may also operate through anthropomorphism, like nonhuman figures in animal fables. Animal characters with human-like attributes symbolically express a certain meaning. Plants also have allegorical meaning. For example, the “Rose” in the medieval allegory The Romance of the Rose symbolizes a young maiden through the personification of this botanical plant. Plato’s “Allegory of the Cave” (Republic 380 B.C.E) is understood more as a thought experiment (OER source). The theoretical work of a philosopher is symbolically represented by Plato’s allegory to explain the role of the philosopher: A philosopher learns from emotional and reactive thinking to rely on and utilize reason in order to understand the real reality beyond human sensory capabilities. For more information, visit OER Allegory of the Cave.

This animation shows how human understanding directly relates to lived experiences CC

This image is of a colorful, artistic cartoon-like representation of the myth of the cave. It simply shows how our own direct experiences limit our understanding. To demonstrate this idea, the left-most portion of this image has an orange wall with shadows projected onto it. In front of these shadows are three men sitting on the floor in chains. They are shown reaching out their arms out toward the shadows as if the shadows were real. Behind the men’s backs is another wall, a yellow brick wall. The source of the shadows comes from this wall where three women in lavender dresses hold up three objects whose shadows project onto the far wall by a live fire, like puppetry. The women hold a Greek soldier, a horse, and a fox. Next to the row of women is a large cauldron, a large pot with flames overflowing it, as its sight source. The flames are bright white, yellow, red, orange, and blue, with an ashy gray trail of smoke lingering at the ceiling of the cave. On the right-side of this representation of the myth of the cave shows two men outside the cave. They realize that the shadows are caused by a fire. One of the men holds his hand over his eyes for shade and the other holds his hand out, palm facing up, to show confusion. This whole scene demonstrates the initial understanding we hold as true by our own direct experiences as we gradually grow from simple cause and effect assumptions to further realizations of the complexities of reality, which must be known through further observation, inquiry, and critical thinking, as well as evidence (Book VII of Plato’s The Republic Wiki).

A framing device in late medieval European allegorical narrative poems, like the French allegorical dream-vision on the ‘lover’s complaint in Old French titled The Romance of the Rose (1230-1275) by Guillaume de Lorris and Jean de Meun is allegorical dream-vision. Allegorical dream-visions begin with its protagonist falling asleep. The narrative that follows is a dream-vision with symbolic and allegorical characters, like the Rose, Friend, Genius, Nature, and Reason. Christine de Pizan wrote dream-visions to reform this tradition.

gender equality is associated with the UNSDG (United Nations Sustainable Development goal number 5. For more information, please visit Key Terms at the end of this book.

A satire is a poem, story, narrative, artwork, or film, for example, exposes questionable social norms or practices in a subtle, concealed manner through allegory, an animal fable, or humor, for example. A satire can evoke humor but addresses serious topics, like Orwell’s Animal Farm (1945). A picaresque novel is also satirical through ‘roguish’ characters. Literary satirists in the Western tradition range from Aesop’s Fables to Greek and Roman satirists Lucian, Horace, and Petronius and Renaissance dramatists Shakespeare, Miguel Cervantes, and Ben Jonson. Enlightenment satirists and recent social critics include the work by Voltaire, Twain, and Ambrose Bierce. For an example of Edgar Allan Poe’s satirical novel, go to The Narrative of Arthur Gordon Pym of Nantucket (1838) OER Satire PYM by Matt Johnson, 2014.

2017 march on gender rights and environmental justice at COP 23 Germany, UN Climate Change Conference CC

This is an interdisciplinary field of study that looks into gender and history, sociology, political science, gendered identities, and gendered violence. The aim is to understand the formation and implication of gender hierarchies and gender within a context, like history. Disciplines include Education, Law, the Arts, Human Services, the Social Sciences, Medicine, Literary Studies, among others. Intersections between gender studies and ecocriticism include ecofeminism. For more information, visit OER Pressbooks.