Chapter Ten The Conclusion of an Introduction to Literary Studies with Sustainability Intersections

On William Shakespeare’s ‘Problem Plays’ on Race, Gender, and Social Justice

Outcomes and Skills Practiced

- Chapter Ten completes course outcomes by featuring Shakespeare’s problem plays

- We continue to identify literary & poetic conventions in early modern drama

- Selected assignments apply ‘ecocritical’ approaches to prepare for a sustainability project

- Themes intersect with gender, inequality, social justice, among others (UNSDG Toolkit)

To many Shakespeareans, ecocriticism seems not to be new

and instead to be like old thematicism and nature studies.

….As a non-environmental writer, the work of Shakespeare… should

be approached without the anthropocentric and ecocentric binary….

Simon Esto, 2005

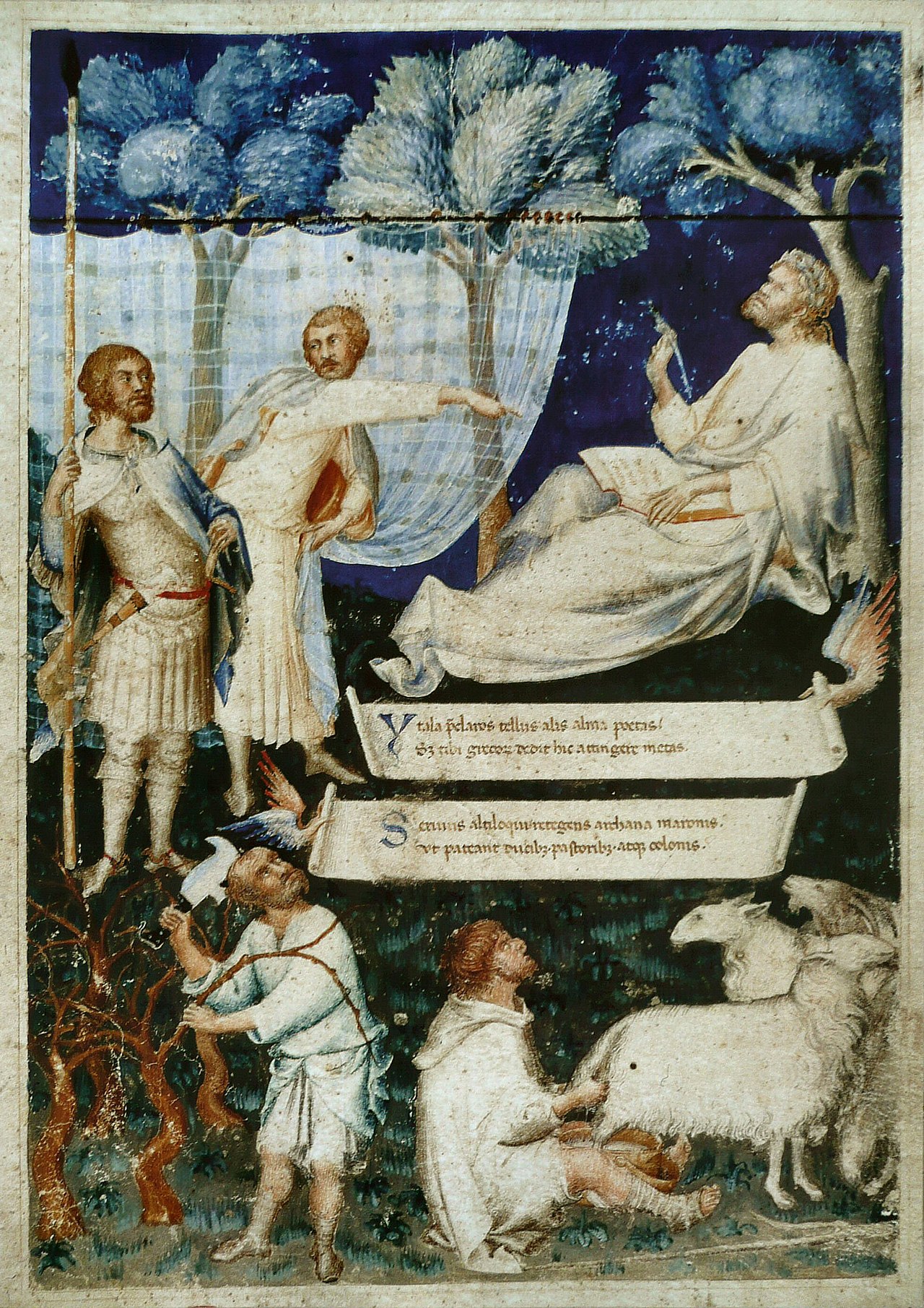

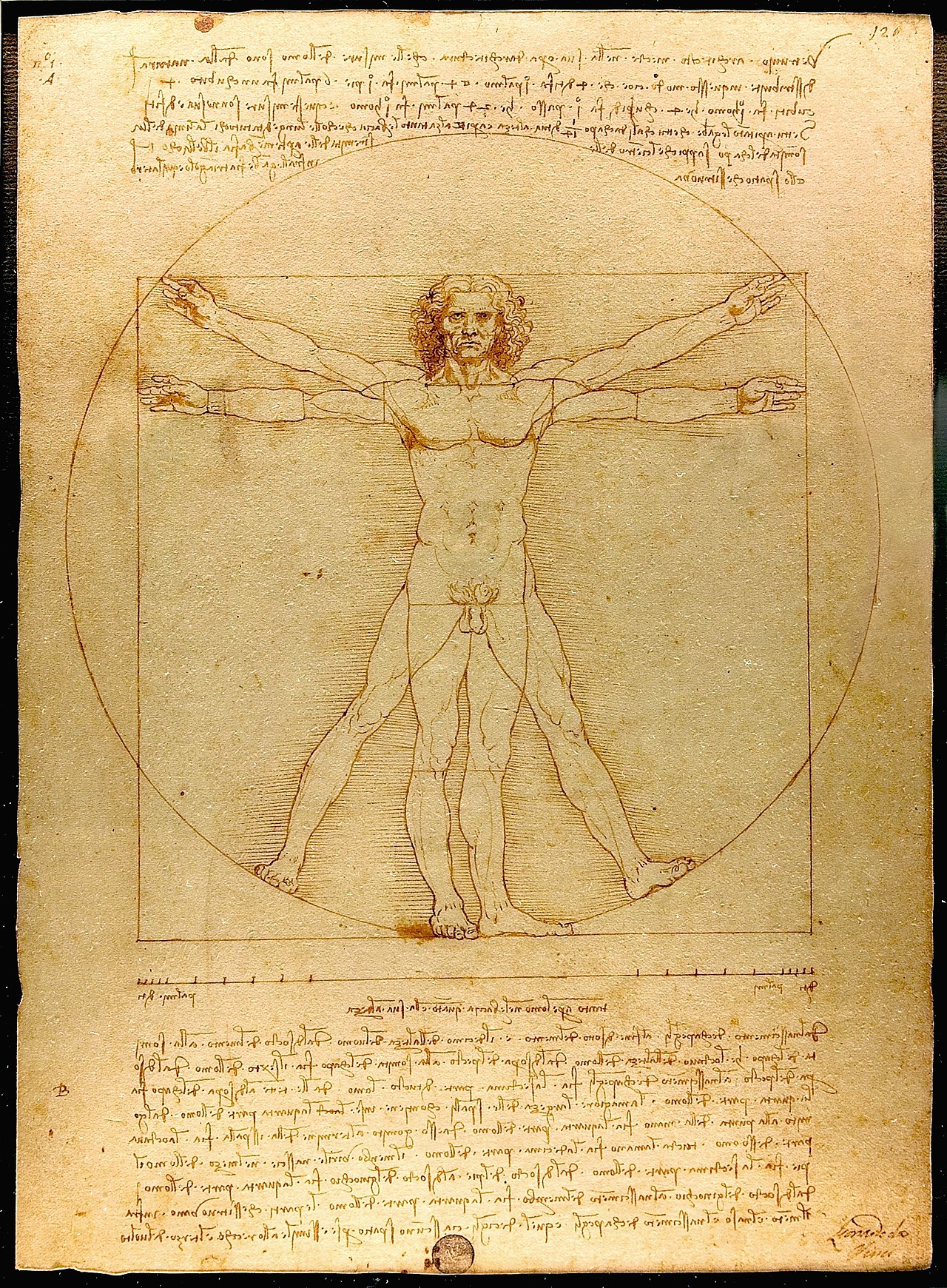

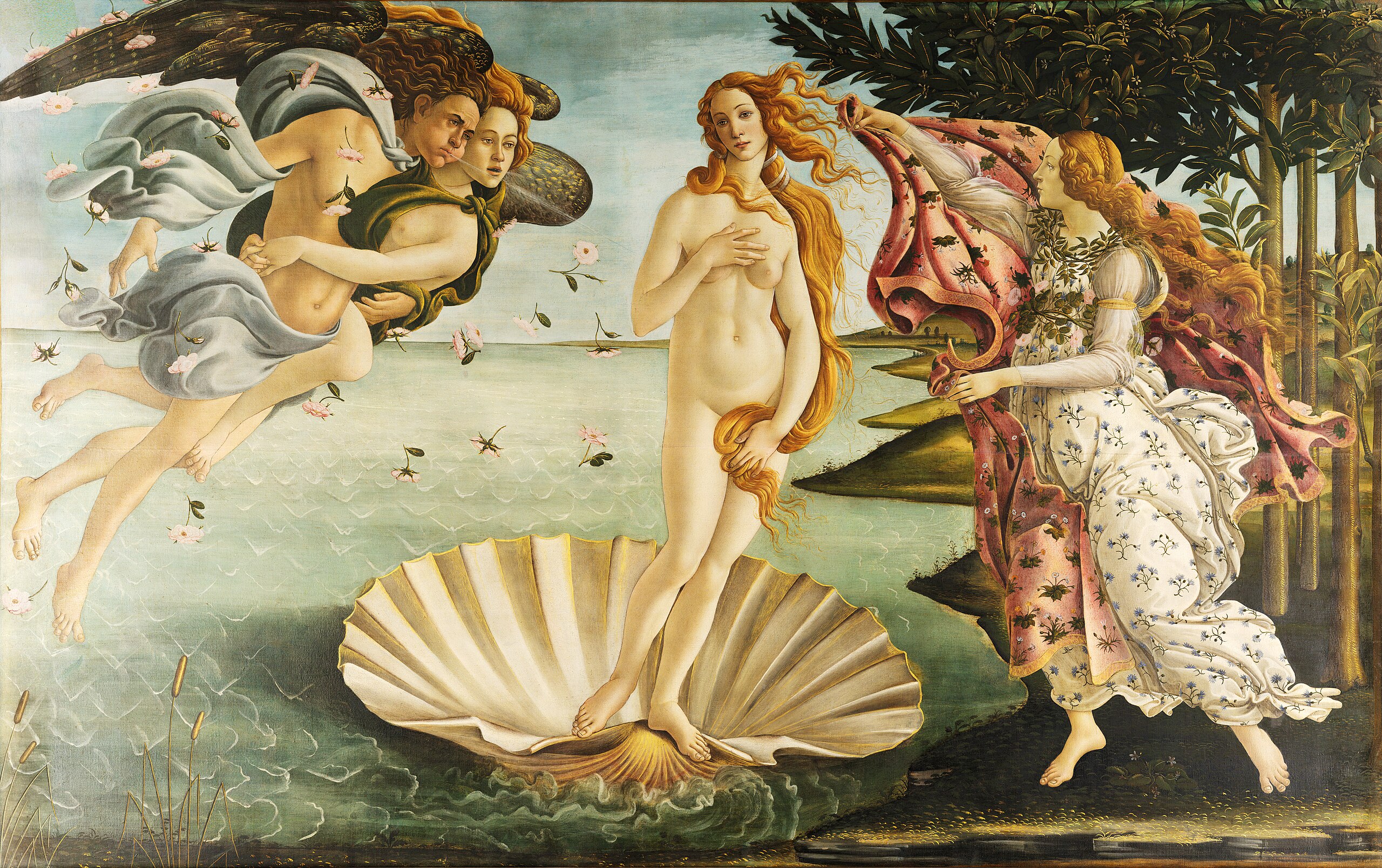

Martini’s 1336 Petrarch’s Virgil, 1490 da Vinci’s Vitruvian Man, 25 C.E. Egyptian Gaia, & 1480 Botticelli’s Birth of Venus (right) CC

On the European Renaissance

Petrarch’s objects of desire, da Vinci’s innovations, Egypt’s Gaia, and Botticelli’s Venus represent the artistic and intellectual splendor of Europe’s cultural revival known as the Renaissance (see images above). At its advent in the mid-1400s through the 1500s, the Renaissance captivated Europeans with rediscoveries of classical antiquities and literature in the arts, humanities, and sciences that were not widely known, since the fall of the Roman Empire in 476 C.E.

Florence, Italy became the center of the Renaissance. Its population boomed to rival Rome where it struggled to recover since the Justinian Plague of 541 C.E. (OER). After the fall of the Byzantine Empire in 1453 to the Ottoman Empire, scholars from Constantinople brought back antiquities to Florence, Italy in the mid-1400s (OER). For the next century Europe’s early modern period emerged with advances in the arts, history, literature, mathematics, music, philosophy, and the sciences. Europeans embraced their classical past and admired ancient heroes in Renaissance art. “To clearly identify one’s past involves the simultaneous identification of one’s present” (Miller 1991). This vibrant cultural revival reached William Shakespeare’s England by the latter part of the 1500s, as Protestantism emerged.

The 1450s Gutenberg printing press accelerated exquisite outbursts of creativity and philosophical productions since the European Renaissance. This technology opened Europe to the world of ideas with popular travel accounts, as new maritime technologies propelled global trade (OER).

By the 1400s people throughout Europe had long been accustomed to the use of spices and other luxury items from Asia. Not long after the Portuguese completed their reconquest and Castilian forces captured Andalusia, Marco Polo embarked on his famous journeys to the Far East. Although not the first European to make contact with China or the fearsome leaders of the nomadic Mongolian Empire, Polo was the first to leave a detailed account of his journeys. OER on Europe’s Renaissance & Technology

On the Early Modern Era and Humanism

Renaissance poets and artists incorporated classical allusions in their own works to create different forms of poetry and storytelling outside of traditional religious contexts that replaced traditional narratives like the medieval miracle play. Following Dante Alighieri, Giovanni Boccaccio, Christine de Pizan, European writers integrated Greek mythology and Roman histories in their own works at a time when the Roman Catholic Church’s stronghold was being challenged. Martin Luther’s critique in the early 1500s is one significant example that marks different cultural trends in religious doctrine. Another example of systemic change in European religiosity is the emergence of Protestantism, which flourished throughout Northern Europe and beyond since the mid-1550s (OER Pressbooks on Luther & Technology). The emergence of humanism reflects new trends in Europe’s intellectualism and religiosity.

“Prayer, to be sure, is the stronger weapon…Yet, knowledge is no less necessary”

(Erasmus of Rotterdam).

Humanism centered on the history of philosophy and transformed Renaissance philosophies – like Cartesian dualism – to privilege humanity over nature, masculinity over femininity, and the integrated over the ‘othered’ (OER On Cartesian dualism in Philosophy). Sequentially, European poets, inventors, and painters did not initially shape Elizabethan cultural works in England since the Renaissance did not reach England until after the mid-1500s.

On Humanism and England’s Jacobean Theater

Artists like Raffaello Sanzio da Urbino and writers like Dante Alighieri and Luigi de Porto influenced Elizabethan and Jacobean humanism and theater. Urbino’s The School of Athens (1510) heightened English artistic humanism and Luigi de Porto’s folkloric 1530 Novella novamente ritrovata [Newly Found Story of Two Noble Lovers] shaped Elizabethan theater as the primary source of Shakespeare’s 1597 Romeo and Juliet, after which Arthur Brooke adapted into English in his narrative poem, The Tragicall Historye of Romeus and Juliet in 1562.

Christopher Marlowe, Ben Jonson, and William Shakespeare are a few English millennial dramatists who were also greatly influenced by and experimented with classical works, including Aristotle’s Poetics, a classical literary theory from 335 B.C.E., and Ovid’s verse (OER Pressbooks on Aristotle & Early Classical & Indian Drama).

The plots of Elizabethan and Jacobean dramas show variations of Aristotelian unities on a wide array of subjects on humanism, on matters of governance and the ministry and representations of nature, which placed nature outside of urban centers – like Shakespeare’s A Midsummer Night’s Dream, Macbeth, The Winter’s Tale, and The Tempest or placed nature within an urban center as anthropomorphized allegory – like Jonson’s Volpone; Or the Fox. Arguably, these dramatic works also questioned established beliefs in the rigidity of supreme rule, extravagant wealth, and human desire. Marlowe’s Dr. Faustus (1592) exposed the hubris of superiority while Jonson’s allegorical satire critiqued the culture of the urban wealthy (OER Marlowe and On Social Contract).

On Literary Studies and Shakespeare

Literary studies in English Renaissance theater challenge learners to closely read Jacobean works on several levels.

- Learners can manage the process of engaging with a poem or dramatic work by William Shakespeare.

- Learners can manage their own learning to avoid taking on too many tasks.

- Always start with a text that is manageable – start with a popular sonnet or scene. View a filmed production of a play before reading the written version.

- Once a text is chosen, simply identify a key passage or scene of intrigue. Then work backwards by reading its source, the scene in the actual written version.

- Learners can read a review of a filmed adaptation that informs on how a specific production interprets an Elizabethan or Jacobean original play.

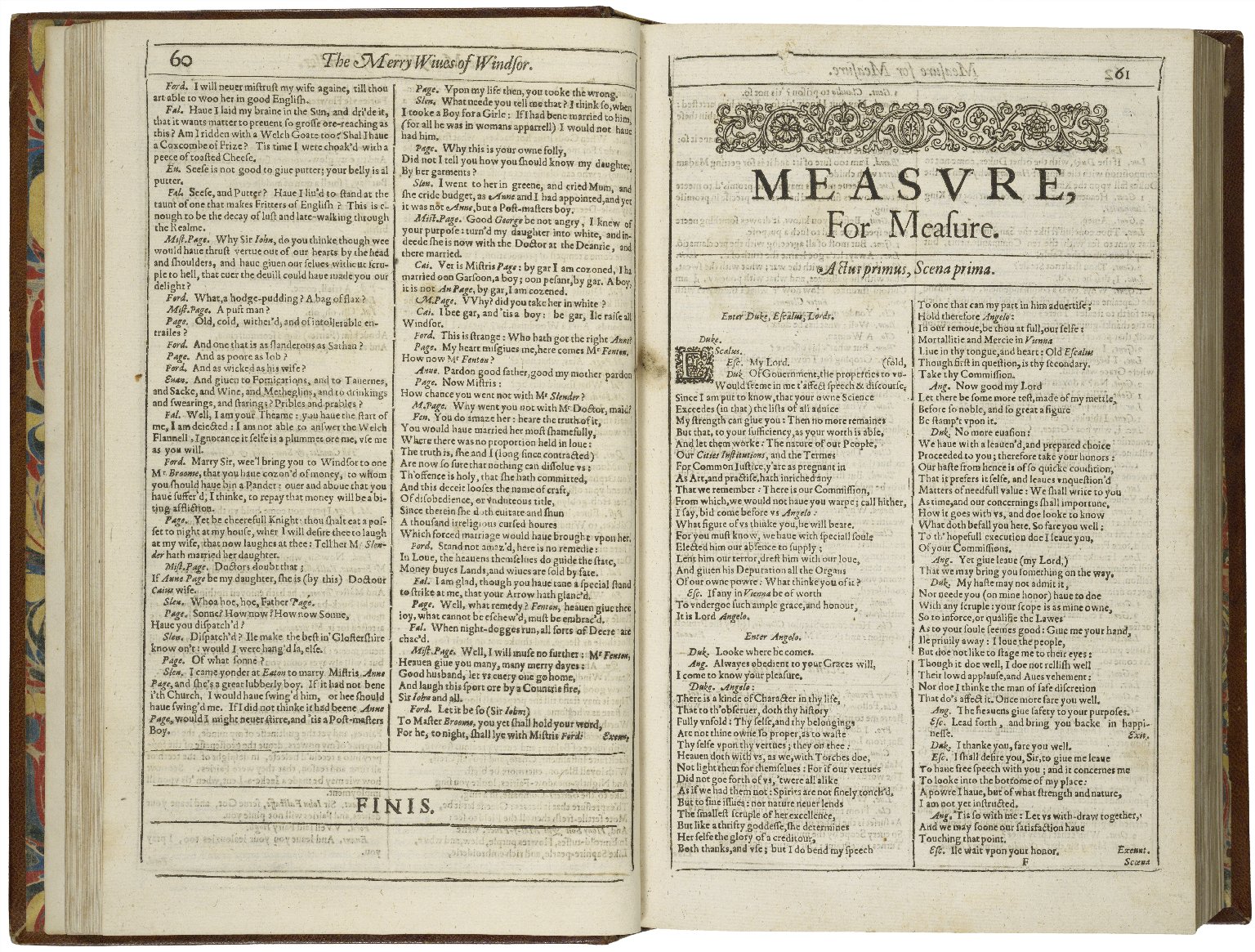

- For example, most libraries offer access to Shakespeare’s Measure for Measure, but since its ending is open to interpretation, numerous productions end the play in diverse ways.

- In addition to critically reading on poetic devices and themes, classical allusions can also be understood by twenty-first century learners.

- Access to source materials is helpful. They offer an understanding of an allusion in an earlier work, as a way to compare their contexts.

- For example, most libraries offer access to Shakespeare’s Measure for Measure, but since its ending is open to interpretation, numerous productions end the play in diverse ways.

Learners may also practice closely reading early modern dramatic works to identify biblical allusions, while engaging in literary studies from the perspective of our own present moment, since none of us can avoid our own cultures and social norms.

On Ecocriticism and the European Renaissance

Europe’s early modern period has been identified by twenty-first century scientists, ecocritics, and philosophers to represent the origins of the industrial revolution – industry accelerated to transform life on earth since the late 1700s as human activity in exploration, colonialism, and global trade aggravated traditional communities and ecosystems alike around the world. English feminist philosopher Kate Soper argues that we must know the present status of and correlations between global overall health and our roles in global trade in our efforts to address present-day sustainability challenges.

“…in view of the latest IPPC and UN reports on the planetary conduction, the urgency of checking growth and changing consumption to meet environmental constraints must be stressed in any argument” (Soper 2023).

Since ecocriticism on European Renaissance theater and Jacobean theater has [ironically] arisen only in the last fifteen years, our initial ecocritical efforts may seem less intuitive or well-founded.

“Early modern scholarship and ecocriticism…continue to pose challenges to one another”

(O’Dair 2008).

However, our efforts in literary studies should result in growth and refinement with practice in textual analysis important in ecocriticism. Familiarity with our present situation on overproduction and consumption along with its economic disparities, such as between the rich classes and laypersons, also inform on present efforts to engage literature on similar concerns and themes (UN Film on Planetary Health). For example, modern human activity has had its byproducts, such as air pollution. In Western literature air quality has been addressed since 400 B.C.E., which is addressed by Hippocrates and Seneca of Rome in 96 C.E.,

“the causes of the unwholesome atmosphere, which gave the air of the City so bad a name with the ancients, are now removed” (Seneca qtd. in Fowler 2020).

Recent ecocriticism on European Renaissance art and literature intrinsically demarcates Europe’s role in current twenty-first century climate stability, ecosystem and wildlife devastations, and sustainability concerns outlined by the United Nations (UNSDG), which go hand in hand with social injustices and labor exploitation.

[European Renaissance] marks a pivotal epoch in the history of the earth. Spurred by the rediscovery of classical learning to rival the grandeur of Ancient Rome and spurred by Columbus’s plundering of the West Indies, European powers studied and exploited the environment with unprecedented zeal, while investing in resource extraction, overseas colonization, and technoscience (OER Article by Borlik 2022).

Europe’s cultural revival was quite extensive and complex. What seems to have started as an artistic and intellectual cultural movement, the Renaissance opened Europe to the rest of the world through maritime travels and colonialism.

These global economic undertakings compounded Europe’s revival with exorbitant amounts of accumulated wealth and access to natural resources extracted from pristine, uncharted territory and waters. The Indigenous communities of the Americas and West Africa saw nothing like it (TED Talk by Anthony Hazard). These endeavors set the stage for Europe’s role in the first industrial revolution, which accelerated in the 1700s. Currently, in the 21st century, we are in the 4IR (Fourth Industrial Revolution), where First World nations – China, the United States, India, and the West – now lead other worldwide nations in aggravating global temperature, due to non-renewable atmospheric, oceanic, and land pollution, like carbon and plastics (OER Pressbooks on 4th Industrial Revolution).

Current Renaissance scholars and ecocritics point to Cartesian ideology to explain how exploitive social norms at the base and sanctioned patriarchal forms of governance and surveillance were upheld throughout the four industrial revolutions. Boundaries between the human and nonhuman and binary thinking – like preferring the human intellect more than the human body – may emulate the Great Chain of Being only to some extent, due to Cartesian ideology. The reliance on binaries in Cartesian ideology reflects an uninformed and unsustainable view of reality and natural phenomena.

When Elizabethan playwrights like William Shakespeare were performing theatrical dramas, distinctions between superior and inferior were aggravated as a global empire began to germinate: English colonialism (OER). Like other critical approaches – Cultural Studies, Marxism, and Gender Studies – ecocritical literary studies on English theatrical works may reveal how its people navigated through a transforming culture with Protestant monarchs at home and colonizing companies with enslaved people abroad while urban centers were erected.

On William Shakespeare, an Elizabethan & Jacobean Dramatist

Biographical details about the historical William Shakespeare have eluded researchers. It is known that he was born and baptized in 1564 and was educated in Latin, performance art, and verse. At age eighteen, Shakespeare married twenty-six-year-old Anne Hathaway and fathered several children at Stratford-upon-Avon, England. When Shakespeare was twenty-five years old his contribution to Elizabethan theater was recognized in London as a poet and thespian. In Samuel Johnson’s preface to The Plays of Shakespeare (1765), he wrote: “His characters…are the genuine progeny of common humanity, such as the world will always supply, and observation will always find.”

William Shakespeare’s corpus extends from his earliest play Henry VI Part 1 in 1590 and narrative poems to his last play in 1611, The Tempest, a problem play. His preserved long poems – Venus and Adonis (1593) and The Rape of Lucrece (1594) – were published during his lifetime, as well as a collection of his sonnets in 1609 by Thomas Thorpe. The rest of his works were published posthumously. Other problem plays of Shakespeare are The Merchant of Venice (1600), Measure for Measure (1605), and The Winter’s Tale (1604).

Throughout his works, emerging themes challenge well-established social orders and confront the strictures and confines of ‘official’ culture in England. Shakespeare’s classical literary allusions throughout his work inspire reimaginings of human desire, the representation of women, and the fluidity of sexualities, and explores governance, among other themes. A prevalent literary trope throughout Shakespeare’s corpus is the role and use of power by those who hold it.

Shakespeare’s Works with Gender & Social Justice Intersections

Power concedes nothing without demand.

It never did and it never will.

Frederick Douglass, West India Emancipation Speech, August 1857

Throughout his dramas, long poems, and lyrical poetry, William Shakespeare’s corpus is heavily invested in gender equality and social justice to address overarching concerns on ideology, superstructure, and governance, which also allude to concerns we share in the present day, like ecological preservation. By his principal female characters, Shakespeare creates themes on forms of power and monarchical rule in dramatic works where female characters also reflect admired historical figures, like Joan of Arc. She appears as Joan la Pucelle, ‘the virgin’ in King Henry VI Part 1 (1590).

1790 engraving of Desdemona & Othello, 1429 drawing of Joan of Arc, & 1790 painting of Juliet in Act 5, Romeo and Juliet CC

The effects of expressions of power is a theme that is a prominent literary trope throughout Shakespeare’s work: on the role and use of power by those who hold it. Shakespeare further develops his themes on female agency with key female figures who must navigate the patriarchal superstructures of European city-states, throughout his works. And, unlike the work of Ovid and Christine de Pizan, for example, Shakespeare’s female characters practice their own agency and, in many cases, this results in tragedy: Juliet in Romeo and Juliet (1597) commits suicide, Desdemona is murdered in Othello (1603), and Cleopatra in Antony and Cleopatra (1607) cannot escape her own Egyptian patriarchal apparatus. Shakespeare’s lyrical poems also represent women.

A large number of his sonnets also address the dynamics and effects of male supremacy upon women. Several poems show the effects of rulers upon people – which include the fate of women – and even nature. Sonnet 94 in particular reflects this literary trope and alludes to the Gaia hypothesis that suggests values that support sustainable ideologies.

For example, Sonnet XCIV expresses a sustainable ideology when the topic of just rule intersects with the well-being of a community and nature:

- In this sonnet Shakespeare describes the connections between the actions of a ruler both upon nature and the community.

They that have power to hurt and will do none, / That do not do the thing they most do show, / Who, moving others, are themselves as stone, / Unmoved, cold, and to temptation slow / They rightly do inherit heaven’s graces / And husband nature’s riches from expense;…(OER Sonnet 94).

Several lines of the sonnet express an advocacy for ‘merciful’ rule.

- For example, the phrase “have power to hurt and will do none” is one example.

- Other lines show the benefits of this form of governance – which imply social practices based on an ideology that honors the ‘Gaia hypothesis’ and the web of life, through merciful means of governance: “They [rulers] rightly do inherit heaven’s graces / And husband nature’s riches from expense.” Here when a ruler governs ‘rightly’ the web of life prevails; is sustained. Hence, we can understand Shakespearean justice to expand human and ecosystem health to ensure overall sustainability beyond human civilization.

- The last line alludes to the benefits of ruling with measured mercy and heart. If a ruler were consistent in withholding from either exercising or abusing power, then corruption is also avoided; greed is tempered. And decisions sway toward just outcomes.

- “…husband nature’s riches from expenses.”

In addition to rhyme scheme and internal rhyme, the use of juxtaposition in this poem emphasizes the tactful and consistent merciful actions of a ruler; as well as its implications to the status of nature. Through poetic devices and themes, this lyrical poem also challenges Cartesian dualism, because it takes ‘human emotion’ – the heart – to lead and rule over a people and the ecosystem with compassion.

Shakespeare’s sonnet brilliantly articulates the role of power to uphold social justice and preserve nature, while also allowing liberty. The idea to rule to support freedom is expressed by the phrase “Who, moving others, are themselves as stone.” To paraphrase, this phrase communicates the idea that those who have the power to rule should be consistent and reliable, as the people live their lives.

Expressions of a sustainable ideology are manifested in the idea that if humanity were to rule mercifully and with conviction, people and nature would not be exploited. This idea derives from Shakespeare’s word choice “expenses,” implying extravagant wastefulness as we “husband nature’s riches” to maintain its health.

Sonnet 94 also proposes a solution for the source of conflict in Ben Jonson’s Volpone; Or the Fox; in order to avoid the tendencies of greed and corruption that spiral out of control and threaten all, we must make efforts to practice consistency in self-regulation to avoid abuses of power.

Shakespeare’s proposed solution is shared in other literary traditions, including those by the Indigenous communities of the Americas and abolition and lyrical poets; the poets featured in this book are Enheduanna, Phyllis Wheatly, Sappho, Etheridge Knight, and June Jordan, among others. Topics from their works are relevant in the United Nations Sustainability Development Guide (UNSDG), especially on peace and social justice, the health of women and children, labor exploitation, and climate instability.

The Shakespearean literary trope witnessed in Sonnet 94 – on the role and use of power by those who hold it – also manifests in his Roman history plays Julius Caesar (1599) and Antony and Cleopatra (1607), tragedies Hamlet and King Lear, and comedies Measure for Measure, The Merchant of Venice, and The Tempest. This chapter features Shakespeare’s problem play Measure for Measure.

Let’s proceed in this chapter to engage with the literary trope on the use of power in Shakespeare’s work and learn more about its intersections with systemic injustices. While doing so, let’s also refine both our analytical and ‘ecocritical’ interpretive talents, as this book comes to a close and anticipates projects on sustainability. Review the global goals of The United Nations Sustainable Development Goals, which collectively ensures a healthy and prosperous future for all, our planet, and its nonhuman life (UNSDG).

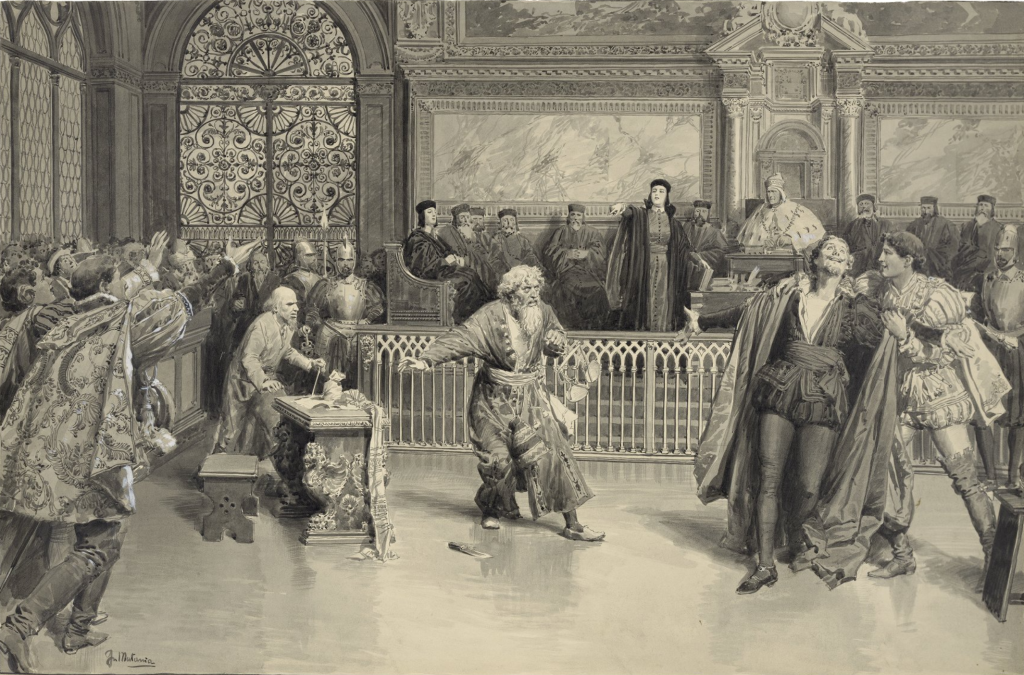

On Shakespeare’s Problem Play: The Merchant of Venice (1600)

Keeping the prevalent literary trope on the role and use of power by those who hold it in mind, let’s explore Shakespeare’s problem plays. These plays are didactic by their complex characters who either partake in or suffer injustices, due to faulty governance that aggravate racism, sexism, and injustice.

For example, The Winter’s Tale represents principal characters who must learn how to manage and navigate King Leontes, who overnight becomes tyrannical. Principal characters who either profit from or are dispossessed by institutional inequalities – like racism and sexism – are represented in The Merchant of Venice and Measure for Measure. The plots of these problem plays are only resolved by marginal characters who become mediators, in order to minimize unjust governance and in turn reduce harm toward the community.

1876 Gottlieb’s Shylock & Jessica, 1600 scene of Portia, The Merchant of Venice, 1899 Porita, & Maurycy Gottlieb (right) CC

Shakespeare’s characterization of Shylock in his second problem play – The Merchant of Venice – demonstrates to audiences ways to approach injustices that have been normalized, like the othering of non-Christians in Europe, of what we know today as systemic racism (OER synopsis, The Merchant of Venice). To learn about an adaptation of The Merchant of Venice set in Washington, DC., go to link: 2022 Folger’s production. To engage with the play proceed by adding annotations and notes on representations of perpetual cycles of oppression, like those that Shylock addresses in a soliloquy.

For example, a soliloquy in Act 4 scene 1 of The Merchant of Venice has audiences witness Shylock’s reasoning to have a ‘pound of flesh’ from Antonio’s heart. His insistence on upholding the ‘pound of flesh’ contract becomes a means of retribution, because Shylock has been experiencing many injuries and injustices by Antonio for simply being a member of the dispossessed people of Jewish ancestry in Italy. Hence, Shakespeare’s Shylock exposes cyclical oppressions toward many peoples at that time period, which also implicate the English.

What judgment shall I dread, doing no wrong?

You have among you many a purchased slave,

Which, like your asses and your dogs and mules,

You use in abject and in slavish parts

Because you bought them. Shall I say to you

Let them be free! Marry them to your heirs!

Why sweat they under burdens? Let their beds

Be made as soft as yours, and let their palates

Be seasoned with such viands”? You will answer

“The slaves are ours!” So do I answer you:

The pound of flesh which I demand of him.

Shylock’s soliloquy exposes the ‘cycles of oppression’ suffered by those of Hebraic heritage and Judaic faith, of those who have experienced multigenerational injustices throughout Europe. These forms of injustices were also commonplace in England since the 1290 Edict of Expulsion, which Geoffrey Chaucer alludes to in “The Prioress’s Tale,” from the Canterbury Tales (OER). While Shylock’s claim to a “pound of flesh” is unlawful, his claim is reactive. It is an extreme expression of ‘an eye for an eye’ form of justice in Judaic law, as demonstrated in the “Book of Exodus” in The Torah, (OER Book of Exodus). Shakespeare’s literary trope on the role and use of power by those who hold it is addressed to negotiate systemic injustices, as Shylock exposes Europe’s institutional racism; hence, implicates English audiences, too.

On Shakespeare’s Problem Play: The Winter’s Tale (1609)

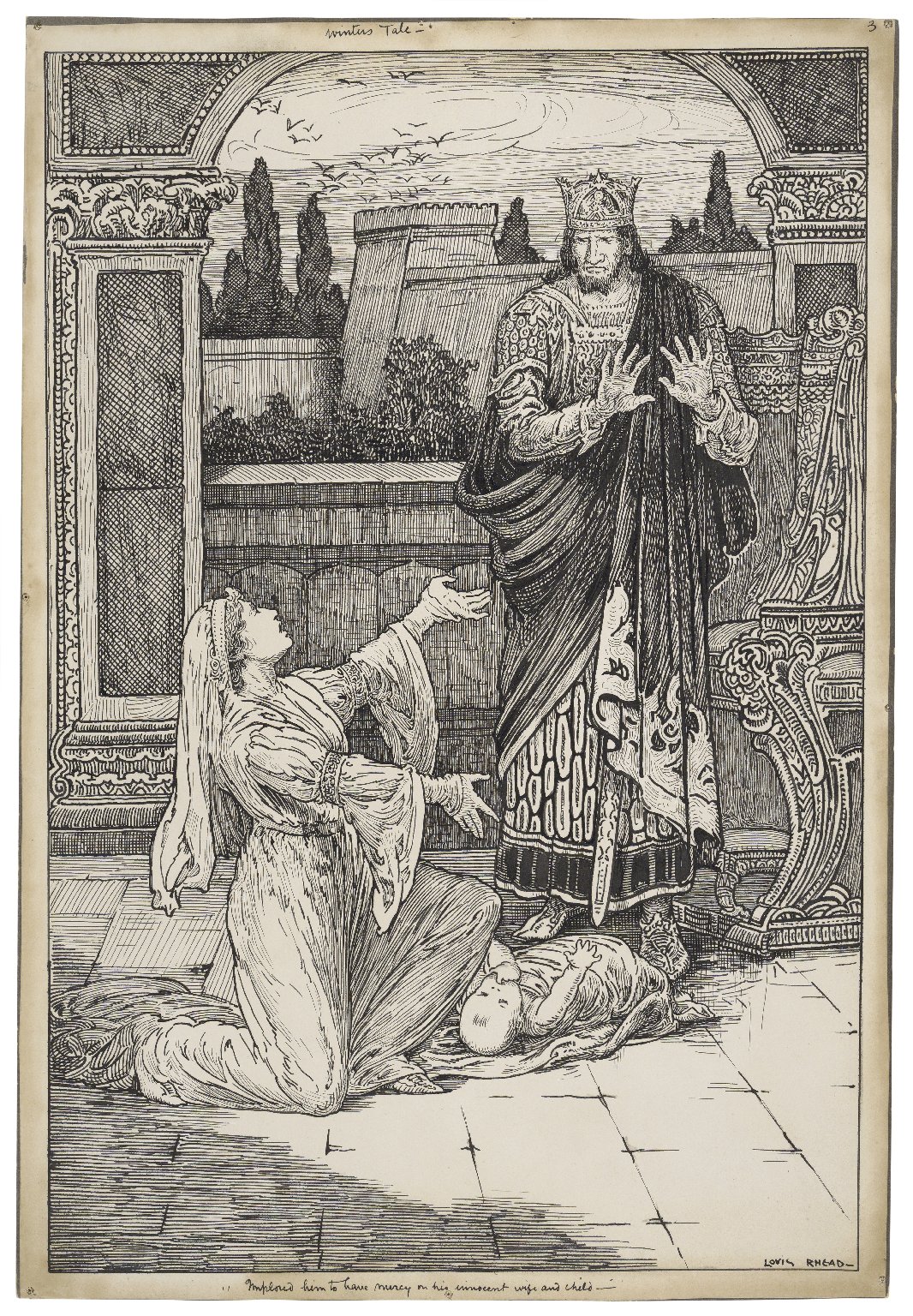

Autolycus (left), Florizel & Perdita dance, Paulina pleads to King Leontes, & Perdita & Florizel, The Winter’s Tale (far-right) CC

A few of William Shakespeare’s dramatic works have been designated as ‘problem plays,’ due to integrating opposite genres. The plots of problem plays unfold in a dramatic hybrid that blends comedy with tragedy. They seem to defy predictable and simple endings; as a matter of fact, they do not resolve easily, if at all. This mixture of literary forms in problem plays enhances the development of paradoxical and complex principal characters.

A motif of Shakespeare’s problem plays is the representation of contradictory characters – Shylock immediately comes to mind, but Antonio and Bassanio are also problematic characters in The Merchant of Venice, as are Prospero and Caliban in The Tempest. To achieve unforeseen resolutions, Shakespeare conjures up characters who tackle the play’s conflict. As mediators, they contribute to the ending and are usually female figures.

Initially, a female figure in a Shakespearean problem play may be a minor character. She may watch tragic events unfold from the margins of the action throughout the play. Yet, she is secretly orchestrating a solution. Portia in The Merchant of Venice is an example of the role of a marginalized female character in a problem play. Throughout the plot Portia becomes a prime mediator of conflict. She navigates the conflict between several characters to avoid a tragic outcome and to secure an ending that simulates a traditional comedy with a marriage, but the union between her and Bassanio is not simple nor stable.

Another Shakespearean problem play with a resolution that is orchestrated by a female character is represented in The Winter’s Tale (1609). In this problem play Paulina orchestrates its unforeseen ending after King Leontes suffered a form of mental illness that manifested as jealous violent life-threatening outbursts towards his wife, Queen Hermione.

For example, after King Leontes falsely accuses Queen Hermione of infidelity, his irrational behavior results in the tragic death of their only son, of the exile of his newly born and only daughter, and the supposed death of the queen herself (OER Synopsis of “The Winter’s Tale”). Sixteen years go by and King Leontes, under the counsel and guidance of Paulina, is sincerely repentant.

I am ashamed. Does not the stone rebuke me / For being more stone than it?—O royal piece, / There’s magic in thy majesty, which has / My evils conjured to remembrance and / From thy admiring daughter took the spirits, / Standing like stone with thee. (Act 5, scene 3 , lines 45-50)

Unbeknownst to the king, Paulina has been secretly caring for and protecting Queen Hermione. Shakespeare’s literary trope on the role and use of power by those who hold it is resolved at the end when repentant Leontes reunites with both his wife and his exiled daughter Perdita (lost in Latin and Spanish), through Paulina’s tactful mediation.

On Shakespeare’s The Winter’s Tale (1609) and Ecocriticism

Ecocriticism of Shakespeare’s work was initiated in the 1990s by the representation of nature in The Winter’s Tale.

For example, ecocritics have relied on a scene set at Perdita’s garden. While gardening, she describes the carnations in her garden as “bastards” of nature, because of genetic engineering. Perdita tells Polixenes,

“For I have heard it said / There is an art which in their piedness shares / With great creating nature” (Act IV scene iv line 104-108).

In other words, she tells Polixenes that she knows that humans alter nature through ‘art’ and she interprets this human activity as inferior to nature itself. Yet, Polixenes reassures her that nature and art are one of the same, an assertion that alludes to Paulina’s orchestrated plan at the play’s end – when she shows her own art collection to King Leontes to show the king a live statue of Queen Hermione.

In The Winter’s Tale, themes emerge to suggest that rulers who make errors may also make amends. This possible outcome in the play repairs the harm committed toward the community and of its legacy – of its children and mothers. Through mediation, The Winter’s Tale resolves the conflict caused by its monarch. Similar to The Merchant of Venice, this theme informs learners and critics alike about Shakespeare’s literary trope – on the role and use of power by those who hold it, because power demands mediation in place of centralized versions.

Each problem plays, The Merchant of Venice and The Winter’s Tale, elevate the role of women to the status of peacemakers who hold wrongdoers accountable. Through a blend of comedy and tragedy, Shakespeare’s problem plays are fruitful platforms for ecocriticism and for projects on sustainability since the plays reflect concerns similar to those addressed by the United Nations Sustainable Guide (UNSDG).

Featuring Shakespeare’s Problem Play: Measure for Measure (1604)

Isabella & Angelo, 1623 Measure for Measure, 2007 Production with Angelo & Isabella, & Pompey Bum with Escalus CC

A Brief Summary of Measure for Measure

William Shakespeare’s first known problem play is Measure for Measure (1603), a problematic comedy that centers on the paradoxes of excessive measures to regulate sexual practices out of wedlock. Excesses to regulate relate to rigid interpretations of scripture or of implementing ruling statues. Its central patriarch is Duke Vincentio. The play unfolds when the Duke decides to delegate an ignored statue on sexual practices. Since King James I of England watched its first production in 1603, many critics argue that the play’s conflict navigates how a monarch should mediate power.

Set in the urban city of Vienna, Act 1 of Measure for Measure begins with a dialogue between Duke Vincentio and Escalus. In a lackadaisical demeanor, the Duke informs Escalus that he is called to leave the city, but wants to enforce an ignored law in his absence that regulates sexual conduct. So, the Duke elects Lord Angelo to enforce this law, due to Angelo’s outwardly righteous display of morality. Yet, soon after, Duke Vincentio reveals that he plans to remain in Vienna in the disguise of a friar to watch the plot he has orchestrated unfold.

For example, in Act 1, when the Duke admits that laws on immoral sexual conduct originate from Christianity, which he has failed to uphold for “fourteen years,” he rationalizes his decision to remain in Vienna disguised as a Friar to test whether his subjects, especially Angelo, can rectify the sense of ‘lawlessness’ that has taken over Vienna. Is Angelo as competent as he projects?

Only this one: Lord Angelo is precise,

Stands at a guard with envy, scarce confesses

That his blood flows or that his appetite

Is more to bread than stone. Hence shall we see,

If power change purpose, what our seemers be.

Ironically, the reasoning behind the Duke’s decision to hand over his power to Puritanical Angelo is to have him enforce the laws in his place. But, the Duke’s decision to remain in Vienna suggests the role of the monarch as the master of disguises in efforts to not necessarily regulate immorality, but expose his subjects’ hypocrisy. The result has the Duke placing numerous characters in an assembly of outrageous scenarios – like comedic bed tricks and confusing identities – to test the moral appearances of his subjects. Character serves as a dramatic device in this play to address its theme.

When instances of regulating behavior are asserted in the play, characters become caught in situations that oscillate between a comedic farce and an existential tragedy. Angelo tragically faces his own existential self when he fails at enforcing his own morality. Commoners must mediate their own fate when they are pursued by rigid regulatory means, like those drunkard Bernadine must navigate. Even Isabella, the play’s novice nun, becomes entangled by the sexual behaviors of family members and strangers. Her own moral righteousness is tested, too. In the case of Angelo, once he becomes the acting Deputy of Vienna, his outward moral appearance begins to fade that ironically results in a firmer adamance against leniency.

Angelo’s lack of a calm, predisposed temperament starts to show when he applies the law and issues drastic decrees to punish violators, actions that even go against the wishes of his own advisors.

For example, Escalus repeatedly tells Angelo not to apply harsh punishments if he is guilty of similar behavior:

Whether you had not sometime in your life / Erred in this point which now you censure him, / And pulled the law upon you (“Measure for Measure” Act 2 scene 1 line 15-18).

Escalus’ advice involves another source of conflict in the play, those that also surround Claudio. Claudio is the brother of Isabella. He is arrested for the crime of impregnating his betrothed fiancé, Juliet. According to Angelo’s interpretation of the law, Claudio’s crime of having sex out of wedlock is punishable by death. Throughout the play Angelo asserts he has not violated any moral law; yet, the Duke as a Friar implicates him anyway to demonstrate his hypocrisy.

In disguise, the Duke fabricates a bed trick scenario. He has Angelo sleep with Isabell out of wedlock. But it is Marianna, his ex-fiancé in Isabella’s place. Ironically, the Duke’s orchestrated comedic bed trick exposes Angelo’s imperfect humanity, because it is disclosed that Angelo broke off their wedding when Mariana lost her dowry onboard a ship that sank.

The play’s denouement climaxes when Isabella exposes Angelo’s moral hypocrisy. Initially, Isabella is not taken seriously, until her unbending pleas to hold Angelo accountable reach the Duke: “justice, justice, justice, justice” (“Measure for Measure” Act 5 scene 1 line 27). Knowing all along of Angelo’s misuse of power, the Duke ends the play by orchestrating four absurd ad hoc marriages. The last words of the play are directed toward Isabella when the Duke himself proposes to her. Isabella refuses to answer.

Shakespeare’s literary trope on the role and use of power by those who hold it in this play involves hypocrisy, denial of one’s own libido, the abuse of power, and institutional sexism. Women’s rights – like the right not to marry or live a life in a nunnery – are dismissed. The theme of this play unveils the absurdity of regulating consensual sexual desire, while exposing how sexual oppression leads to sexual abuse of others, like Angelo’s exploitation of Isabella.

Shakespeare’s literary trope on the role and use of power by those who hold it emerges in Measure for Measure through Duke Vincentio, Lord Angelo, and novice nun Isabella, who either hold power, assert it, or challenge it, like Isabella. She penetrates the glass ceiling of gender injustice of its patriarchal superstructure.

An Analysis of Measure for Measure (1604) in its Literary Devices

Measure for Measure is a phrase taken from the Christian Bible. It also has roots in Judaic law. The phrase alludes to Jesus Christ of Nazareth’s speech in Matthew 7:2 who discusses the ethical practice to not accuse others of an offense that accusers also hold – to adhere to the ethical duty of avoiding hypocrisy to uphold social cohesion. Another premise of the title expresses the ethical practice of fair retribution, as Judaic law states.

For with what judgment ye judge, ye shall be judged:

and with what measure ye mete, it shall be measured to you again

To complicate and develop its title, the theme of Measure for Measure involves excessive means taken to appear moral through regulating one’s own and the behavior of others, which is an early modern form of Foucault’s panopticon explored in The Disguised Ruler (2016) by Dr. Kevin Quarmby of MIT and explored in Surveillance Studies (OER). The title appears at key moments throughout Measure for Measure to develop motifs on tempering hierarchical methods of controlling social behavior.

Even though this play is set in Vienna where the Roman Catholic Church lost its last stronghold, its title also alludes to Protestant England and the Puritan factions of the late 1590s and early 1600s. Its plot unfolds to position characters in paradoxical situations that challenge their own moral standards that are not necessarily measured against others or written law, but against how to interpret and understand established decrees in a modernizing England. Characters find it difficult to honor decrees in practice, including the play’s patriarch, Duke Vincentio. Disguised as the Friar, the Duke can witness how established decrees are carried out as he moderates their impact, including those by acting Deputy Angelo.

At first Angelo is hesitant about his new appointment, but almost miraculously he becomes a committed enforcer overnight. His decrees to regulate and punish those who violate sexual misdemeanors – prostitution, premarital sex, and abandoning one’s children – follow strict interpretations of the law to include capital punishment. When Claudio is arrested to be executed for impregnating his fiancé, his friend Lucio visits him in jail. Claudio insists on Lucio to go see his sister Isabella who resides at a nunnery and ask her to dissuade the acting Deputy Angelo from executing him.

In Act 1 scene 4, Isabella demonstrates sound judgment when she asserts that Claudio simply has to marry Juliet to uphold moral law; yet Angelo’s impractical interpretation of the law ironically obstructs morality.

ISABELLA O, let him marry her!

LUCIO This is the point.

The Duke is very strangely gone from hence;

Bore many gentlemen, myself being one,

In hand, and hope of action; but we do learn,

By those that know the very nerves of state,

His givings-out were of an infinite distance

From his true-meant design. Upon his place,

And with full line of his authority,

Governs Lord Angelo, a man whose blood

Is very snow-broth; one who never feels

The wanton stings and motions of the sense,

But doth rebate and blunt his natural edge

With profits of the mind: study and fast.

Lucio describes Anglo as an injudicious enforcer of the law who rules without emotions and lacks compassion. Angelo’s rectitude reflects a Puritan belief system due to his strict interpretation of the law. Audiences start to question Angelo’s ability as Vienna’s acting deputy and even his character. Is Angelo fit to rule?

When Isabella speaks with him, Angelo’s response to her pleas for a merciful treatment of the law exposes his alarming rigidity in enforcing the law itself. For example, Isabella asks Angelo to be merciful in applying the law. Angelo remains adamant.

ANGELO Be you content, fair maid.

It is the law, not I, condemn your brother.

Other scenes also show how characters navigate Angelo’s interpretation of established decrees. A well-known scene between Pompey Bun and Escalus addresses the paradoxes of morality and regulating sexual behaviors.

Isabella appeals to Angelo (left), Shakespeare’s Poetry (center), Pompey Pun, & Players in Measure for Measure CC

In the play Escalus serves the residing Deputy Angelo and Pompey Bun works at Vienna’s version of what we know today as the red-light district. Their conversation about morality and the law takes place in the streets, which resonates Angelo’s impractical interpretation of the law and the absurdity of enforcing it simply through punishing the most vulnerable.

ESCALUS How would you live, Pompey? By being a bawd? What do you think of the trade, Pompey? Is it a lawful trade?

POMPEY If the law would allow it, sir.

After this brief exchange entertained by Pompey’s wit and logic, its following dialogue exposes the absurdity of the law, again through Pompey.

ESCALUS But the law will not allow it, Pompey, nor it shall not be allowed in Vienna.

POMPEY Does your Worship mean to geld and splay all (to spay) the youth of the city?

On Measure for Measure (1604) & Psychoanalysis

Psychoanalytic critics explain the play’s motif on the hypocrisy of judging the sexual conduct of others when the accusers themselves also share the same desires, through Freudian readings. Representations of repressed forms of sexual desire are understood through the two principal characters – Isabella and Angelo. This suggests that public mandates that regulate human behavior have been emotionally internalized to evade accusation and punishment, and unbeknownst by these characters.

When Angelo reasons with Isabella to have her yield to him so he can satisfy his own sexual drive, her word choice seems to eroticize her own body. Psychoanalytic critics argue that Isabella’s own understanding of moral righteousness is a sign of her own sexual repression.

ISABELLA That is, were I under the terms of death,

Th’ impression of keen whips I’d wear as rubies

And strip myself to death as to a bed

That longing have been sick for, ere I’d yield

My body up to shame.

Paradoxically, while Isabella asserts the integrity of her own control over her own body, the imagery of her words disassociate purity from her body. Rather, they imply deeply buried desire. Nouns like “whips,” “rubies,” “bed”, and “strip” imply sexual repression – whips associate pain upon the body and rubies emulate blood droplets, for example. Shakespeareans identify Isabella’s own sexual repression by her word choice. Similarly, psychoanalysts also understand Angel as sexually repressed. Angelo, Vienna’s acting Deputy, also expresses pent up, restrained sexual desire.

For example, when Angelo proposes that if Isabella were to submit to him, he assures her he will pardon her brother Claudio from execution.

ANGELO Plainly conceive I love you.

ISABELLA My brother did love Juliet,

And you tell me that he shall die for ’t.ANGELO He shall not, Isabel, if you give me love.

ISABELLAI know your virtue hath a license in ’t

Which seems a little fouler than it is

To pluck on others.

When Isabella threatens to expose his corruption, Angelo responds by asserting more power. This suggests his own awareness of his power as a Deputy and for being male.

Fit thy consent to my sharp appetite;

Lay by all nicety and prolixious blushes

That banish what they sue for. Redeem thy brother

By yielding up thy body to my will,

Or else he must not only die the death…

Hence, regardless of the presumed agency Isabella thinks she has by embracing both the edicts of the law and the nunnery, it dissipates when the patriarchal superstructure is confronted. The sexual repression of Isabella and Angelo seems symptomatic of the culture they reside in.

Angelo’s treatment of Isabella simply hints at what is not allowed to be revealed or spoken of, immoral practices like slavery and the exploits of natural resources throughout colonialism. Caught within a corrupt web, Isabella is instantly reminded of the ideology that sustains the patriarchal superstructure. Yet, Isabella can be adamant, too. She is committed to exposing Angelo’s abuse of power and hypocrisy to bargain sex for her brother’s life.

Ovid’s Metamorphosis may have influenced Shakespeare to address the fluidity of sexual desire and failed attempts to regulate it. And Christine de Pizan too, since her work also exposes institutional sexism and systemic misogyny through her debates on sanctioned rape in medieval romances and her literary works to represent women’s intelligence, integrity, and morality. Gender Studies may shed more light on Shakespeare’s characters and may also inform the causes of self-imposed sexual repression.

On Measure for Measure, Gender Studies, & Course Outcomes

Once a close reading of the play is conducted, learners may interpret this play as Shakespeare’s efforts to expose the mechanisms that sustain systemic misogyny and institutional sexism. This approach to textual analysis in Gender and LGBTQ+ Studies may also inform on the paradoxical characterization of Isabella to unveil her role and contribution in the play. These interpretations may also inform on Shakespeare’s representation of the ideal woman, who embraces archaic rules and regulations and faces a disillusioned bildungsroman in silence, as witnessed in his characterization of Isabella.

This play addresses the theme of Shakespeare’s Sonnet 94 – on the role of the ruler over the ruled, even if Measure for Measure does not end with merciful judgements for all; the injustices that Isabella suffers under Angelo’s authority continue by Duke Vincentio’s proposals.

Throughout Shakespeare’s problem plays, a mediator emerges to pacify and resolve conflict. This motif is witnessed by the role of Portia in The Merchant of Venice and Paulina in The Winter’s Tale. In Measure for Measure, Claudio appoints Isabella to mediate between him and Angelo. The Duke asks Isabella to mediate between Angelo and Mariana, to play a bed trick. And, Mariana asks Isabella to mediate between her and the Duke to pacify his wish to execute Angelo. Isabella must also mediate for herself to advocate for the injustices she suffered by Angelo.

For example, when Angelo proposes to pardon her brother if she would allow him to have sex with her, Isabella remains firm, and states

Ha! Little honor to be much believed,

And most pernicious purpose. Seeming, seeming!

I will proclaim thee, Angelo, look for ’t.

Sign me a present pardon for my brother

Or with an outstretched throat I’ll tell the world aloud

What man thou art.

This moment in the drama Isabella asserts an unbending sense of morality and consistency, qualities that Sonnet 94 expresses for a merciful and just ruler. The symbolism of Isabella’s gender emphasizes that which unjust patriarchal rule excludes: the human heart.

Shakespeare’s Isabella preserves Angelo’s humanity by vowing to hold him accountable for his moral transgressions. She elevates human integrity as witnessed in Christine de Pizan’s works in taking the community into account.

Yet, Isabella’s climatic proclamation is followed with Angelo’s disheartening response to her moral rectitude. His words resonate a somber, yet righteous tone of their own that haunts.

Measure for Measure reaches its climax with Angelo’s rhetorical question:

His words devalue Isabella’s agency to speak and leaves her in an existential stupor.

ISABELLA To whom should I complain? Did I tell this, / Who would believe me?

ANGELO Who will believe thee, Isabel?

His words devalue Isabella’s agency to speak and leaves her in an existential stupor.

ISABELLA To whom should I complain? Did I tell this, / Who would believe me?

Angelo’s rhetorical question and Isabella’s placement as his inferior add a new dimension to the play’s theme on morality and regulating human behavior. It calls for interpretive approaches that involve intersectionality between gender studies and institutional sexism, because the moral dilemma of the play is now institutional, as Angelo affirms his authority.

ANGELO My unsoiled name, th’ austereness of my life,

My vouch against you, and my place i’ th’ state…

By positioning Angelo as one who entertains power and its uses to affirm systemic gender inequality, Shakespeare’s literary trope emerges for audiences to witness what is not easily seen or admitted by those in governing roles: institutional sexism.

The climax demonstrates the stranglehold of an ideology that sanctions systemic inequalities, an ideology that reflects Cartesian fractures between the body and mind and men and women. Yet, while Angelo firmly claims his position while attempting to diminish the agency of others, the Gaia hypothesis prevails. The interconnectedness among all life on earth is not invalidated by arrogant control and oppression, but it can be threatened if those in power do not recognize the implications of their actions, like Angelo.

At the close of the play, Shakespeare’s Duke Vincentio does see, up to a point. While he sees the fruits of his labor by affecting the outcomes to hold actors accountable, he professes his love to Isabella. Her silence encourages the Duke to ask again. And again, she is silent. Her silence speaks volumes, as she continues to navigate her culture through its margins.

On Measure for Measure and Approaches to Intersections

Shakespeare’s Measure for Measure serves as a platform to learn more about intersections that involve sustainability.

Learners have several options on how to proceed to identify and negotiate intersections that this play allows for:

- on gender and governance,

- on ideology and systemic gender inequality,

- on the intersectionality that Sonnet 94 also allows for, on governance and the health of nature.

To show a few possible directions in our interpretive approaches, let’s review the preliminary pages on ecocriticism and intersectionality of this textbook. For example, let’s review Joni Adamson’s literary study on intersections between ecocritical topics in the literature of the Indigenous communities and environmental devastation. A critical intersection is identified by Joni Adamson: violence against women.

On Institutional Sexism & Nature in Measure for Measure (1604)

The work by Joni Adamson reminds us that literary studies involves intersections and critical approaches to those intersections – like ecocriticism and gender studies – assist us to link what may seem as unrelated areas of inquiry. These avenues for inquiry in literary studies ultimately inform real-world twenty-first century concerns and challenges, like systemic sexism. They also reveal fruitful readings of the dynamics behind misogyny and ecophobia, a hatred toward women and nature.

For example, #MeToo finally gained momentum in 2017, even though it began with Tarana Burke of Selma, Alabama in 2006. She responded to a reported sexual violence experience with “Me Too” in Myspace. The scholarship of Holland and Hewett on Gender Studies echo Adamson’s own study on how Indigenous literature and intersections that involve violence.

#MeToo has inspired work not only in memoir but also in poetry, fiction, creative nonfiction, graphic narrative, and writing for stage and screen….Poets such as Audre Lorde, Adrienne Rich, Maya Angelou, Marge Piercy, June Jordan, Sonia Sanchez, Cherríe Moraga…[and] authors like Toni Morrison, Gayl Jones, Maxine Hong Kingston, Marilyn French, Alice Walker, and Sandra Cisneros…[call] for a retheorizing of rape and its representation predicated on the understanding that ‘all violence is, in fact, sexual violence.’ (#Metoo & Literary Studies: Reading, Writing, and Teaching About Sexual Violence and Rape Culture 4-5)

Our revisit of William Shakespeare’s Measure for Measure calls for ‘retheorizing’ to continue work on identifying the links between violence against women with other forms of violence by interpretive approaches in ecocriticism and gender studies.

Joni Adamson asserts in her own work, American Indian Literature, Environmental Justice, and Ecocriticism: The Middle Place (2001) the same fruitful avenues for literary inquiry, as do Holland and Hewett. Intersections of storytelling and human-made environmental degradation are unveiled in Adamson’s work. Joni Adamson shows that scholarship on Maya literary history by Laguna Leslie Marmon Silko informs our current efforts to address sustainability, social justice, and the climate crisis. Adamson’s featured intersectionality in 2001 mirrors Holland and Hewett’s work in on the #MeToo movement in 2021.

“Readers must make some connections between the sexual violence of women, the historical objectification of people of color, and the objectification of violence of the body of Mother Earth” (Adamson 148).

On Shakespeare’s Measure for Measure (1604) & Ecocriticism

Ecocritical Shakespeare (2011) by Bruckner and Braydon asks, “Can reading, writing about, and teaching Shakespeare contribute to the health of the planet?” Their own answer challenges us all to revisit literary works to rethink our own ecocritical approaches in literary studies.

“Scholars of early modern drama identify in these works ‘a sincere concern for the human impact on the biophysical environment’ and its resultant effects” (3).

The question posed and the answer also elevates literature to the role of informant and ally in our time of climate and social justice crises.

- Since the beginning of this book, cultural leaders Chimamanda Ngozi and Diné share their own storytelling traditions to emphasize the fluidity of the narrative and of its many communities and languages.

- In English translation, this book offers stories in cuneiform in Sumero-Akkadian and Akkadian, glyphs in Maya, tales in Anishinaabe, Taíno, and Cherokee, epic in Mandingo, and classical Western and Eastern story collections in Persian, Arabic, Hindi, ancient Greek, vernacular Latin, French, Spanish, English and Italian.

- Stories travel like people do. And no one tradition exists alone, not even the Mayans of the Popol Vuh.

Framed by these storytelling cultures and traditions, this book ends with a closer journey into the corpus of Shakespeare. Yet, let’s also tread lightly to witness literary moments that inform and support an ‘ecocritical’ interpretative mindset.

For example, Measure for Measure and intersections between institutional sexism and representations of nature

Perhaps the most urgent environmental threat we see in Shakespeare’s plays is industrial militarization. Shakespeare registers its multi-scaled destruction of human and non-human life in late-medieval English warfare and nascent imperial regimes such as Henry V in France and Claudius’s in Denmark. Besides the iron-making which caused deforestation, guns large and small needed saltpeter for gunpowder. It was made from composted manure taken by government officers from private barns and privies. These forced appropriations clashed with farmers’ efforts to feed growing numbers of people and animals. And they sparked England’s first country-wide but ultimately unsuccessful environmental protests. Shakespeare’s Climate Crisis

Key Points

- European Renaissance & Gutenberg Printing Press in English Elizabethan and Jacobean theater

- Jacobean theater arose with English colonialism and ecological and human rights exploitations

- Rise of humanism and Cartesian dualism in poetry and theater

- The Elizabethan sonnet with intersections on gender and ecocriticism

- Jacobean theater has classical & Christian allusion and symbolism

- Shakespeare’s problem plays with institutional inequality, gender and ecophobia intersections

- Focus on intersections throughout Shakespeare’s Measure for Measure and Gaia Principle

- UNSDG on gender equality, reducing inequalities, and social justice on systemic sexism

Media Attributions

- Gaia-Isis in a medallion © Wikipedia is licensed under a Public Domain license

- Hercules and the wagoner © Wikipedia is licensed under a CC0 (Creative Commons Zero) license

- Desdemona with Othello © Wikipedia is licensed under a Public Domain license

- Profile of Joan of Arc © Wikipedia is licensed under a Public Domain license

- Romeo and Juliet, act V, scene III © LUNA: Folger Digital Image Collection is licensed under a Public Domain license

- Scene from the Merchant of Venice © LUNA: Folger Digital Image Collection is licensed under a Public Domain license

- Miss Ellen Terry as Portia © LUNA: Folger Digital Image Collection is licensed under a Public Domain license

- Fawcett as Autolycus © Wikipedia is licensed under a Public Domain license

- Scene from the Winters tale © LUNA: Folger Digital Image Collection is licensed under a Public Domain license

- 1505 of Orpheus in Book © Wikipedia is licensed under a Public Domain license

- Isabella © LUNA: Folger Digital Image Collection is licensed under a Public Domain license

- 1559 Indigenous weeping women © getarchive logo is licensed under a Public Domain license

- Angelo Measure for Measure © Wikipedia is licensed under a CC0 (Creative Commons Zero) license

- Mexico’s La Llorona © Wikipedia is licensed under a Public Domain license

- lost city z © Penguin Random House is licensed under a All Rights Reserved license

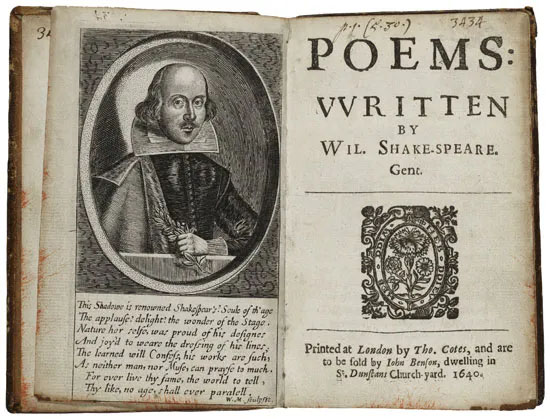

- Shakespeare’s Poems © Britannica Kids is licensed under a CC0 (Creative Commons Zero) license

- Smirke, Robert, 1753-1845; ‘Measure for Measure’, Act II, Scene 1, the Examination of Froth and Clown by Escalus and Justice © Wikipedia is licensed under a Public Domain license

Definitions of literature range from ’written’ works of poetry, the story, the narrative, film, and dramatic works – with numerous subgenres – to including any written, spoken, or otherwise recorded work like podcasts, and radio. Works of literature are frequently categorized in a genre that reflects a specific form. The tradition of designating a genre dates back to Aristotle’s Poetics in 335 B.C.E. Since the late 1990s in academia, definitions of literature include two more designations – ‘popular’ and ‘serious’ literature, as in commercial or traditional and canonical works. Cherokee First Nations and Indigenous scholar Daniel Heath Justice recognizes the “privileged status that literature holds in the Western tradition as ‘serious’ literature, which resonates associative binary and colonial legacies of “civilized and savage” treatment of a people and their literature (Justice 2018). Yet, Justice also acknowledges that, along with other social groups, representing a culture with their own literary tradition empowers their communities, regardless of the privilege of canonical works. Any literature course should utilize works of literature that have been canonized alongside uncanonized works. Some texts are traditionally canonized – like Ovid’s Metamorphosis (6 C.E.) and Ben Jonson’s Volpone; Or the Fox (1606). But, others have only been recently incorporated – like the hymns of Enheduanna, Sappho’s poetic fragments, and Arabian Nights. This last one originates from a complex Persian and Middle Eastern literary tradition that has been historically viewed as popular, until recently (Horta & Seale 2022). As Justice affirms, “Literature as a category is about what’s important to a culture, the stories that are privileged and honored, the narratives that people – often those in power, but also those resisting that power – believe to be central to their understanding of the world” (Justice 20). For more information, visit OER On Literature.

when a literary work references a person, place, event, or from another literary work. Visit Key Terms for more details.

Context refers to how and when information is presented. For example, to understand a historical fact – like African slavery in the Americas – it is important to know its context: when did this human violation begin, where, by whom, and why. Context is the background information of a historical fact. Visit Key Terms for more details.

Humanism is understood as a concept that denotes many aspects of the European renaissance, a cultural revival movement. Specifically, though, humanism signifies the human as a master of his universe; where we can seek within ourselves for answers while we also appreciate our shortcomings and inner contradictions. Humanists placed humanity’s life at the center but still advocated Christian values. Humanism also reflects moral philosophy, history, poetry, and language aesthetics. Unlike Puritanism, humanists were more concerned with intellectual development and less about the immorality of the soul. They valued early antiquity and Christianity while critiquing medieval culture and society. Education was key, as was the matter of virtue (masculine power as moral). Becoming learned served your virtue. Michel Montaigne considered himself a humanist whose philosophical concerns resided on morality.

Cartesian dualism is also known as the Cartesian tradition of Western religious thought whereby the human body and an imagined view of the human soul are understood as separate. Visit Key Terms for more details.

The narrator is the voice of a story and informant in explaining a plot to readers within a narrative. Their point of view can be in the first person, second, third, and omniscient. The narrative is the story itself. A novel can be defined as a substantial narrative with many characters with a main plot and several subplots that usually stretches over a long duration and can have several settings and timelines. There are many sub-categories of the narrative.

Aristotle and Poetics; Aristotle was a student of Plato, who shared his criticism of early poetry: Greek drama, the epic, and lyrical poetry in what has become to be known as Poetics (335 B.C.E.). Visit Key Terms for more information.

unities, according to Aristotle’s Poetics (350 B.C.E.) addresses the timeline of a Greek theatrical work. Visit Key Terms for more details: *Aristotelian unities.

A satire is a poem, story, narrative, artwork, or film, for example, exposes questionable social norms or practices in a subtle, concealed manner through allegory, an animal fable, or humor, for example. A satire can evoke humor but addresses serious topics, like Orwell’s Animal Farm (1945). A picaresque novel is also satirical through ‘roguish’ characters. Literary satirists in the Western tradition range from Aesop’s Fables to Greek and Roman satirists Lucian, Horace, and Petronius and Renaissance dramatists Shakespeare, Miguel Cervantes, and Ben Jonson. Enlightenment satirists and recent social critics include the work by Voltaire, Twain, and Ambrose Bierce. For an example of Edgar Allan Poe’s satirical novel, go to The Narrative of Arthur Gordon Pym of Nantucket (1838) OER Satire PYM by Matt Johnson, 2014.

A formal academic discipline, Literary Studies seeks to understand literature in its totality through its disciplinary subsets like literary history, literary criticism, literary theory, schools of thought, and multidisciplinary scholarship like Gender Studies, Cultural Studies, and Film Studies. As an academic discipline, engagements in Literary Studies always look into language usage in literary history and literary traditions. “Literary Studies is concerned with the ways that language is used. If it isn’t concerned with language use, it isn’t Literary Studies. Literary Studies is about the ways in which writers use the formal resources of literature to represent and comment upon life” (Aphorisms on Literary Studies). A Literary Studies course with an ecocritical interpretative approach aims to learn from different disciplines and various literary traditions. Its purpose is to expand traditional literary inquiries in order to articulate more concrete understandings of the human-nature binary, environmental challenges, and social justice. These intersections allow learners to identify representations of nature to investigate cultural norms practiced and become informed on the role of ideology in storytelling traditions. Storytelling traditions include various branches of Literary Studies, including on the literary traditions of Indigenous communities, American Studies, Black Studies, Comparative Literature, English Studies, Ethnic Studies, and World literature. The combination of literary traditions in literary studies enhances learning experiences that both inform and challenge learners and educators alike to address themes associated with sustainability, like those proposed in the United Nations’ Sustainable Guide (UN's Guidelines). “The end of literary studies is a discussion of how literary writers use formal rhetorical devices to represent life, thereby giving us new ways to understand and experience our world…the end of literary studies is not, for example, the recognition that Milton used blank verse in Paradise Lost. The end of literary studies is a discussion of how Milton used blank verse in Paradise Lost to associate the Christian empire he represented with the English nation” (Aphorisms on Literary Studies). This approach to literary studies aims to enhance collaborative engagement by its coursework, lesson plans, and group projects that contribute to our viable futures.

(“eco” in Greek is household, ecology is the learning of the life of populations)

What is ecocriticism? At first sight, it is simply a literary theory to learn about nature in literature; when critics approach literature to learn about nature, they are offering ‘ecocritical’ interpretations. Ecocriticism aims to not reduce nature into a concept or social construct, which the Western tradition shows in the majority of its literary traditions. Literary studies offers a platform to learn about representations of nature in texts, while analyzing themes on social injustices, which may share similar treatments, since “ecocriticism is a theory that seeks to relate literary works to the natural environment” (Estok 2005). Another explanation is “the study of the relationship between literature and the physical environment” and “takes an earth-centered approach to literary studies” (Glotfelty and Fromm 1996). Another explains that, “Ecocriticism examines the representation of and relationships between the biophysical environment and texts, predominantly through ecological theory” (Chisty 2021). Since the 2000s, ecocriticism has relied on scientific and philosophical approaches to understand humanity’s place in the world. The UNSDG offer a wide-ranging view of aspects of human’s roles to address current injustices and the climate crisis. Partly, it is “committed to effecting change by analyzing the function – thematic, artistic, social, historical, ideological, theoretical, or otherwise – of the natural environment.” Ecocritical readings on environmental injustices can intersect with social injustices, like Langston Hughes’ poem expresses. *Go to the section on Langston Hughes’ poem A Dream Deferred in the introduction of this book. This class supports intersections between social injustices and environmental ones. The work of Joni Adamson, American Indian Literature, Environmental Justice, and Ecocriticism: The Middle Place (2001) features the literatures of Indigenous communities and literary analyses with ecocritical understandings to address and expose Western abuse of nature and the causes of our current environmental crises, while demonstrating the literary and storytelling traditions of Indigenous communities as ‘an alternative’ theory. For more information, visit OER on Ecocriticism. This literary theory stems from the first wave of environmentalism in the U.S. by ecofeminism. The term ecocriticism emerged in the article Literature and Ecology (1978) by William Rueckert and an earlier work in 1972 by William Meeker The Comedy of Survival: Studies in Literary Ecology. “First wave" environmental criticism concerns itself with conventional nature writing and conservation-oriented environmentalism, which traces its origins to the work of Ralph Waldo Emerson, Henry David Thoreau, and John Muir. "Second wave" environmental criticism redefines the environment in terms of the seventeen Principles of Environmental Justice and increasingly concerns itself with "issues of environmental welfare and equity" and "critique of the demographic homogeneity of traditional environmental movements and academic environmental studies” (17 Principles of Environmental Justice). A modern third wave of ecocriticism recognizes ethnic and national particularities and yet transcends ethnic and national boundaries; this third wave explores all facets of human experience from an environmental viewpoint” (Adamson 2009). Originally, ecocritics looked at the relationship between literature and nature – between culture and the global environment. Literature shows human tendencies to anthropomorphize nature. Ecocritics see culture as hierarchical and in contrast to nature, especially in Western texts. To analyze this relationship, nature needs to be distinct from human constructs: the wilderness, scenic sublime, countryside, and domestic picturesque. Man-made factors are social orders and political constructs like culture and poverty. Yet, the ‘setting’ of narratives may also be fantastic – as in folklore, the gothic, and science fiction, and hence is also fertile soil for ecocritical readings. Ecocriticism takes as its subject the interconnections between nature and culture, specifically the cultural artifacts of language and literature. As a critical stance, “it has one foot in literature and the other on land; as a theoretical discourse, it negotiates between the human and the nonhuman" (Glotfelty and Fromm qtd. in Sandner 2000). The roots of the environmental movement can be traced back to the abolition movement, which revealed the connections between colonization, conquest, slavery, resource exploitation, and capital, and many of the most successful strategies of early environmentalism were borrowed from the abolition, civil rights, and women's movements and American Indian Land Claims lawsuits. For this reason, “any history of environmentalism that did not include W. E. B. Du Bois, Rosa Parks, Martin Luther King, Jr., or Cesar Chavez, among others, would need to be revised” (Adamson 2009).

Coined by Klaus Schwab of the World Economic Forum, our current historical moment since the early 2000s is designated as the Fourth Industrial Revolution and has become widely known since his 2016 publication. The Fourth Industrial Revolution navigates online technologies throughout major sects of society at a global scale – commercial, communication, education, manufacturing and production, and consumption. New technologies have not only transformed these traditional sects, but has also made them dependent upon them. “The concept of the Fourth Industrial Revolution affirms that technological change is a driver of transformation relevant to all industries and parts of society” (Columbia University). For more information, visit OER on The Fourth Industrial Revolution.

In the Cartesian tradition of Western religious thought the body and soul are understood as separate. This duality is an example of Descartes' understanding of humanity as a spirit, affiliated with the immortal soul, and the body with the finite, or death. Rene Descartes also asserted that animals have no consciousness, unlike humanity. Descartes as the father of modern philosophy introduced the idea that humanity is distrustful or critical of sensory experiences and of the human imagination, meaning that scientific observation is not entirely objective. Empiricism was greatly critiqued by Descartes. For more information, visit OER Pressbooks on Cartesian Thought.

In the European Middle Ages, the ‘Great Chain of Being’ represents a neo-platonic understanding of the cosmic order. This view is borrowed from Aristotle, but includes a blend of Christian theology where motion is controlled by the Christian God through orders of angels; “heaven and earth are intimately connected” (Joseph 2005). A Western notion of scala natura, or grand scheme of the universe, the Great Chain of Being is a hypothesis of cosmic order that places all natural phenomena and humans in a hierarchical order of spiritual inferiority to superiority. Classical views of the Great Chain of Being associate the lower forms as ‘lifeless’. This cosmic order is understood as a series of planes whose ascension is toward Platonic “perfect forms,” where they ascend toward their sources within a Ptolemaic (Earth at the center), geocentric view of the universe.

The theme of a narrative or a play is the general idea or underlying message that the writer wants to expose. In Elizabethan Theater, “John Milton states as explicit theme of Paradise Lost to 'assert Eternal Providence,/And justify the ways of God to men.' Some critics have claimed that all nontrivial works of literature, including lyrical poems, involve an implicit theme which is embodied and dramatizes in the evolving meanings and imagery” (OER Elizabethan Theater). Whether you define it as the overarching subject matter of a text or its message, identifying themes in literary studies establishes initial skills in describing, summarizing, and offering a commentary to a piece of literature, without additional theoretical approaches. Yet, some research is helpful - of its historical era, culture, and geographic region.

A literary trope is a recognizable plot element, theme, or visual cue that has figurative meaning. It can appear within the body of an author’s work, within a tradition, and across cultures as witnessed in world literature and world mythology. A common literary trope is the hero’s journey, which is a plot structure found in stories all around the world. Many literary tropes may not be universally understood, but occur commonly within a specific tradition – like in gothic and fantasy literature, and also in popular comics. Another recognizable literary trope that is observed in Western letters is the symbolism of skulls, like the skull Shakespeare’s Hamlet holds when he delivers his “Alas poor Yorick” soliloquy. In this scene, the skull represents a contemplation of one’s morality in the face of contradicting desires. Yet, as a religious Catholic trope a skull is associated with Jesus of Nazareth, for example. This association may signify more directly with death. Yet, in most religious contexts, skulls are associated with the life-cycle. For example, a skull in Mexican cultural traditions represents this meaning, through rituals associated with the Day of the Dead. They involve visiting and speaking with the deceased at nearby cemeteries, among other rituals; here, the skull signifies the life-cycle. The skull may also share associations with the serpent, like in Chinese and Mesoamerican traditions. Yet, the ‘serpent’ in most Western texts –the New Testament, Ovid’s Medusa, and even popular texts like Harry Potter – is usually associated with demons and the unholy, a finite view of the life-cycle. Another literary trope common in European literary texts is the color ‘white’. In many instances this color means death when associated with snow. Witnessed in James Joyce’s 1914 story “The Dead” from Dubliners, snow is a metaphor that signifies the death of a beloved and of a marriage (Wiki on Joyce's "The Dead" from Dubliners).

“A more or less systematic ordering of ideas with associated doctrines, attitudes, beliefs, and symbols that together form a more or less coherent philosophy or Weltanschauung for a person, group, or sociopolitical movement” (APA Dictionary qtd. BU Equity Guide). In schools of thought such as political science and psychology, ideology is addressed as a system of beliefs that underpins and sustains the form of a society. A school may be supported by an ideology of curricular vigor that rewards certain achievers. The economy of a country may be supported by a capitalist ideology. But, ideology is also understood through other worldviews and cultural norms, like those practiced by the Indigenous communities of the Americas.

In literary criticism, critics analyze the actions of key characters, and one purpose in doing so is to explain whether certain characters are ‘active’ in the plot itself, through choices and independent action – this is agency. Shakespeare’s Isabella in Measure for Measure and Shahrazad in One Thousand and One Nights are examples of characters whose agency drives the narrative.

The Gaia hypothesis is also known as the Gaia principle and Gaia Theory. The Gaia hypothesis realizes the life-giving forces of life on Earth, which dictate a worldview that is more ecologically sound and grounded like Indigenous thought. The concept that “Earth is a single organism” was popularized and accepted by modern scientists in the 1970s (Abou-Agag 2016) when British chemist James E. Lovelock and U.S. biologist Lynn Margulis coined the “Gaia Hypothesis” after the Greek Earth goddess (Britannica). They proved the importance of conceiving of things as a whole in science, a similar perspective known to Indigenous people like the Lakota, which Vine Deloria Jr. and Daniel Wildcat explain in Power and Place: Indian Education in America (2001). This principle is addressed by Deloria and Wildcat in their explanation of Indigenous metaphysics. Lakota philosophy also overlaps with recent understandings of the Gaia hypothesis. Again the ‘interconnectedness’ of the planet to sustain life is a worldview shared by many cultures, including the Lakota of the American plains region (Deloria). “With the entire Earth unified in this way, it seems artificial to distinguish between the parts that are obviously alive (the biota) and the inanimate oceans, rocks, and clouds. These inanimate parts are tightly coupled in chemical processes with the biota”(Abou-Agag 2016). In the 1970s Microbiologist Lynn Margulis and Chemist James Lovelock continues Goldsmith’s work on the Gaia hypothesis, as those who formulated this hypothesis and who “introduced into it the further complexity of the chemical reactions between the atmosphere and rock surfaces as they weathered (a process that bacteria can accelerate) and also the oceans full of algae.” The result was a chemical model of a complex interconnected chain of reactions whose ultimate effect was to regulate the conditions on Earth for the benefit of its life forms. “As Edward Goldsmith writes in The Way: An Ecological World-View, ‘What is required is a totally non-mechanistic theory of life and such a theory must by its very nature be holistic. Living things are alive because they are part of a whole.’ The main features of living things, those that make them alive – their dynamism, creativity, intelligence, purposiveness – are not apparent if one studies them in isolation from the hierarchy of natural systems of which they are a part" (qtd. in Sandner 2000).This model he called Gaia (Abou-Agag). For more information, visit OER Pressbooks on Classical Mythology & OER On Gaia by Harvard Edu.