Chapter Three: On the Epic with Sustainable Communities & Climate Action Intersections

Outcomes and Skills Practiced

- Identify and practice close reading skills on the epic and the narrative (character, plot, setting)

- Practice textual analysis to identify the mythological figures and roles in the epic (epithets)

- Close read of key passages on the hero’s journey (theme, trope, bildungsroman, & others)

- Enhance critical reading with ecocritical interpretative approaches(representations of nature)

The challenge of scale, complexity, and agency are problems of narrative.

Stories require that we construct a world, the setting into which we place

an agent who undertakes an action.

But what kinds of stories should these be?

Martin Puchard, Literature for a Changing Planet

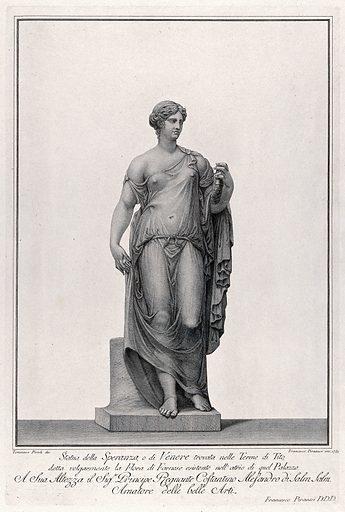

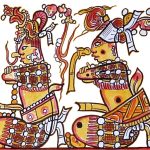

Gilgamesh’s Ninsun control’s the wind (left), Spain’s El Cid, Italy’s Venus, Maya captives 785 CE, & Mali Calvary (right) CC

Introduction of Chapter Three

Our profound question of ‘where do we come from?’ evokes a universal quest for answers witnessed in ancient epics and pre-writing cultures. While the previous chapter features such questions in the origin stories of the Haudenosaunee, Anishinaabe, Taíno, and scholarship on African American storytelling, this chapter elaborates on the epic, an episodic narrative with oral tradition origins later preserved as a written literary tradition. Fragments of ancient epics continue to be found on clay tablets (with ancient writing systems), on parchment (made of animal skin) and papyrus (made of plant-based materials). Epics are compilations of separate stories, of tales that are woven together to create a linear narrative. Let’s begin to identify themes in literature by working with a West African tale (activity below).

What Do You Presently Know about Textual Analysis Beyond Theme in Literature?

What is Theme in Storytelling Traditions and its Intersection with Equality?

GOALS: To build on textual analysis skills, to identify, and to explain theme in a mythological story

INSTRUCTIONS: Theme in literary studies refers to an overall subject matter, argument, or message of a piece of literature. The theme of a story, for example, is not always obvious, transparent, or agreed upon. Read or listen to the following West African story: OER West African tale “Wisdom and the Human Race” by Barker

-

- Listen or read for basic familiarity

- Annotate and take notes on the storyline, plot, and characters

- Identify the main topic, by explaining its general subject matter and focus

- Lastly, identify its theme. To do so ask, What message is expressed about the main topic? Your answer will address the theme of the story. Another question to consider is, How does the story “Wisdom and the Human Race” advocate for equality and community-centered social values? Your insights should address its theme and its message in this folktale.

NOTE: *Source of story and its written version: West African folktale: “Wisdom and the Human Race” by Barker

What Key Aspects of the Epic Reflect Ancient Oral Traditions?

Oral epics are found in cultures all around the world – throughout the African continent, Near East, Middle East, India, China, Southeast Asia, Australia, Europe, Russia, and the Americas and Caribbean. Most ancient epics address the deeds and feats of its heroes. These protagonists negotiate aspects of human civilization – like on the roles of nature and natural resources, establishing social norms of order or social cohesion, or ways to appease deities to win their favor or to temper the hubris of rulers. In many instances, the epic reveals concerns over territory and its resources.

World mythology also reflects oral epics preserved in writing like India’s Ramayana, the West African Malian Epic of Sundiata, and the Mycenaean Homeric epics, The Iliad and The Odyssey. Throughout these epics, the hero navigates adversaries who threaten social cohesion and stability. Many epics share oral storytelling techniques that assist storyteller’s memory and commonalities in theme and form, including epithets, literary tropes, and representations of nature.

The epic was a performed oral storytelling tradition. The earliest known written version of a performed epic is the Epic of Gilgamesh that dates from 2500 B.C.E. Available to us in writing today, this ancient epic seems modern with a tone that enchants and teases audiences with promises of fantastic events.

For example, the poet’s tone in the opening lines of the Mesopotamian Epic of Gilgamesh (2500-1200 BC) enchants audiences by relating the fantastic feats of its hero Gilgamesh.

Let me proclaim to the land (the feats) of him

who has seen the deep Of him who knows the seas,

let me inform it fully He has (seen/visited)

The wise (one) who knows everything. Secret things

He has seen, what is hidden to man (he knows)

And he brought tidings from before the Flood

These opening lines from the Epic of Gilgamesh show the inherent heroic culture of early ancient epics.

What Are Epithets in the Epic?

Literary historians and cultural studies scholars recognize the contributions of early creation and origin mythological stories to our own storytelling practices in the twenty-first century. For example, The Epic of Gilgamesh represents an early flood story, a literary trope that is also included centuries later in the “Book of Genesis” and the cosmogony of Greek mythology. In many cases flood stories in the epic reveal human unsustainable agricultural practices. In regard to Genesis, Bennett argues that “This makes the flood a likely candidate for portraying the environmental chaos that accompanies the disorder of sin. Exploiting the environment is unsustainable. It is effectively ‘uncreating’” (Bennett 2014).

In addition to literary tropes like flood stories, epics – like The Iliad and The Odyssey – also present symbolic mythological figures with specific characterizations, known as the epithet. A form of symbolism, an epithet is an attribution associated with a key character’s inherent talent, like the epithets of Poseidon as ‘earth shaker’ and Zeus with ‘thunder’ in Greek mythology. In many cases, early examples of epithets in ancient epics associate human attributes with nature. These instances are telling, since these epithets associate male gendered deities with talents that assert efforts to have power over nature, or at least a cultural norm of an anthropocentric treatment of natural resources. These examples in literary studies are fruitful in ecocriticism, feminism, among other literary theories.

Other attributes and symbols associated with heroes, come in the form of:

- Owls as a symbol represents Athena and her wisdom in Greek myth

- Capes are symbols in their attire of a hero, like the cape of Superman and the visor of Wonder Woman. The cape reflects his attributes of defeating a villain who threatens humanity, and her visor alludes to her attributes to Diana and Artemis – a female warrior with masculine characteristics and powers.

Think about your favorite comic book heroes.

“We personally may relate with the hero’s associations and values, even in modern-day versions which are the vestiges of long-ago epic heroes.”These symbolic attributes reveal certain values that we as a culture embrace and share. We personally may relate with the hero’s associations and values, even in modern-day versions which are the vestiges of long-ago epic heroes. While modern-day video or table-top role playing games blur the lines between the ancient role of literature and entertainment, let’s proceed to learn more about the rich culture of storytelling, like symbolism (OER SAGA).

What are Examples of Symbolism as Literary Trope?

Trees in early creation myths serve to symbolize the web of life that binds a community with other life forms on earth, and even with the cosmos. Trees in world literature hold sacred meaning since these early stories often relate to a religious doctrine. Trees are key symbols in many origin stories around the world, including the Biblical “Book of Genesis,” which has the story of the Garden of Eden and the Maya Popol Vuh, a Mayan creation mythological story of Mesoamerica. Trees appear as much in Eastern traditions as in Western texts.

India’s Bodh Gaya, a Buddhist sacred site, Ceiba, Maya Tree of Life, and Christian symbol of the Cross CC

Epic poems feature heroes. In several epics they seek immortality, a theme closely associated with the founding of homeland or empire. Yet, for the Anishinaabe, it is the intimacy with the land, ocean, and sky that takes precedence.

The landscape around them originates from a floating tree that unites the gods of another world with their own people by the goddess Antaensic – Sky Woman – in their own world known as Turtle Island. For the Romans, it is the quest of twin heroes Romulus and Remus who founded Rome. They were protected by the fig tree. And in the Epic of Gilgamesh, the quest for immortality represents sustainability concerns of a civilization in Mesopotamian Uruk – today’s region of Iraq. Gilgamesh’s epic journey results in tending a garden. These epic heroes who emerge in ancient mythological stories confront universal questions about life and death, fate, and mortality through the symbolism of the tree. The cycle of life and death is intertwined. Commonalities throughout works of literature are known as literary tropes.

What Are the Literary Tropes of the Early Oral Epic?

A literary trope is a recognizable plot element, theme, or visual cue that has figurative or metaphorical meaning. It can appear within the body of an author’s work, within a tradition, or even across cultures in world literature and world mythology.

A common trope is the hero’s journey – in oral traditions these stories usually involve twin heroes. This plot element is found in stories all around the world. Any literary work in verse is considered poetry, as Aristotle affirmed in Poetics. Yet, oral traditions inhabit both styles of poetry and prose.

Prose has its origins in oral traditions too, as in speeches, sermons, and creation myth. Any community that shares dramatic, poetic, or storytelling traditions constitutes value placed on a work of literature.

Scholars in literary studies identify overarching literary tropes in early storytelling oral traditions. Some of these tropes may reveal how a culture negotiates their own lived experiences, as a displaced people who gain a sense of place and identity through their own storytelling tradition. For example, the hero’s journey of an epic can reveal how its culture values a cosmic sense of permanence. Other epics may reveal an ideology of empire building, through the actions of its epic hero. Epics may also represent how its culture negotiates dualities: light and darkness, the cosmos and the earth, human civilization and the wilderness, and heroism and villainy. Their stories – originally retold in oral traditions – present key characterizations and themes witnessed across world literature, which are then seen as tropes. Literary tropes also represent archetypal characters witnessed in the ancient Mesopotamian odyssey Epic of Gilgamesh and Maya culture and mythology Popol Vuh.

“…these ancient epics seem modern with a tone that engages and teases audiences with promises of its fantastic events.”

The fantastic feats of the hero or heroes of an epic show a culture’s religious doctrine, ideological social practices, and norms, and reflect the day-to-day lived experiences of the community members. The epic also shows a culture’s effort to express what it means to be human.

For example, the hero’s journey in the Sumer, Babylonian Epic of Gilgamesh presents a set of challenges to test its hero. The lines below are from a scene that shows Gilgamesh as obstinate. His hubris emerges through his unbending insistence on killing the god of the forest, Humbaba, so he can attain its lumber, a resource Gilgamesh associates with establishing his own legacy.

‘But whether you come along or not,

I will cut down the tree. I will kill Humbaba,

I will make a lasting name for myself,

I will stamp my fame on men’s minds forever.’

(Puchner 2020)

*Another translation

‘I am determined to cut them down, so that I may gain fame everlasting.’

Gilgamesh spoke again to Enkidu, saying:

‘Now, O my friend, I must give my orders to the craftsmen,

So that they cast in our presence our weapons.’ OER “Epic of Gilgamesh”

Ecocritics point to Gilgamesh’s hubris to demonstrate how his insistence on killing Humbaba, the protector of the forest, reveals Mesopotamia’s need for natural resources beyond their own territory. Narrative moments like these enrich interpretative approaches like ecocriticism, because ancient cultures, like our own, were also challenged with resource scarcity, due to human overconsumption and preoccupations with building legacies. The rise of urbanization then and now are not examples of sustainable cities.

What are the Common Features of the Epic

The form of the epic with it narrative recited or written down verse – lines of poetry – is composed of several common elements witnessed in early world literature and religious scripture:

- Characters associated with the cosmos and supernatural

- The invocation of a muse by the poet as messenger and storyteller

- Narrating from the ‘middle of the action’

- Epithets

- A hero’s journey

- And negotiating and resolving conflict

What Are the Narrative Elements of the Epic?

The narrative elements of the epic include the following, oral epics

- Are rooted in performance and ritual and represent both nature and social norms

- Show a diversity of ancient languages and religious practices across geographic regions

- “Hence, the supernatural qualities of most epic heroes establish and reaffirm the epic as a text that also folds in scripture – the imagined world of gods who interact with humans.”Are long narratives in verse, with some exceptions written in prose. The literary epic in verse is known as ‘epic poetry’.

- Share common character tropes in the epic is the presentation of mythological figures who achieve fantastic feats and interact with deities. Hence, the supernatural qualities of most epic heroes establish and reaffirm the epic as a text that also folds in scripture – to imagine gods who interact with humans.

- Are relevant to their cultures and peoples.

That is to say, through its storyline, plot development and characterization, as well as its creative array of literary merits – like foreboding, symbolism, evocation of the gods, and presentation of a hero’s journey, the epic teaches social norms and values, while it reveals challenges about sustainability, either in urbanization or natural resources, for example.

Close-reading Exercise on the Epic

GOAL: To build textual analysis on the epic and to build ‘interpretive’ approaches as learner’s gain familiarity with its form. This short writing activity also builds on critical reading and thinking skills.

INSTRUCTION: Read the opening lines of Tablet 1. Note the praises by an omniscient narrator of Gilgamesh, king of Uruk. This heroic epic opens to address the attributes of its central hero Gilgamesh and sets up the ‘conflict’ of the plot. Identify the characterization of Gilgamesh. Then, identify the source of conflict in this epic. What pushes the plot? *Note: These deities are also mentioned in Enheduanna’s hymns.

How do the Maya Express Cosmic Representations of Nature?

The Maya creation mythological story the Popol Vuh is part of their Almanac, a tome of works utilized to educate the working classes with narrations on health and medicine, political and social history, the status of exhausted natural resources, and a calendar to predict astrological phenomena. These texts would theorize how to be human. Early Maya poets also believed that their poetry itself came from the cosmos.

From within the heavens they come,

The beautiful flowers, the beautiful songs.

Our longing spoils them,

Our inventiveness makes them

lose their fragrance.

(León-Portilla, Broken Spears 1980)

What are the Narrative Elements of Literary, Written Epics?

While early, ancient epics from oral traditions are tales and stories that come from various different religious cults that are woven into a sequential episodic cohesive plot, written literary epics reflect modern technologies in their composition. Yet, they also share similar narrative elements from the oral epic, like literary tropes, the archetype, epithets, symbolism, and theme, among others.

The Roman epic The Aeneid, El Cid in Spain, and John Milton’s Paradise Lost (1667) are examples of written literary epics. Their storylines involve the founding of recent civilizations and empires and pay homage to the oral epic tradition in form and storytelling tradition. Milton’s epic poem is one example; another is Dante Alighieri’s La divina commedia (1322); and, of course there are mock epics that satirize a culture’s social norms – like Thomas Morton’s New English Canaan (1637), which satirizes Puritan belief, and Alexander Pope’s The Rape of the Lock (1712), which mocks the values of contemporary English aristocracy.

Examples

GOAL: To become familiar with literary forms and its variations, like the epic

DIRECTIONS: Compare with the opening lines from Epic of Gilgamesh at the beginning of this chapter.

THIS IS THE ACCOUNT of when all is still silent and placid.

All is silent and calm. Hushed and empty is the womb of the sky….

The face of the earth has not yet appeared.

Alone lies the expanse of the sea, along with the womb of all the sky.

There is not yet anything gathered together.

All is at rest. Nothing stirs. (Popol Vuh, p. 67)

How Do Epics Inform on Modern-Day Sustainability?

Ecocritic and world literature scholar Dr. Puchner revisits the epic to address our current climate crisis also known as the Fourth Industrial Revolution – a concept coined in 2011 by German engineer and economist Klaus Schwab (Brookings Institute). Puchner’s purpose in placing the epic within the context of our present climate and sustainability challenges is to propose new efforts in literary studies to engage and interpret the literary works of world literature, including ancient epics, to gain new insights from their storytelling that reveal their interactions with the natural environment. For example, the hero’s journey intersects with the culture’s exhausted use of nearby natural resources in the Epic of Gilgamesh.

Hesiod, an early Greek writer of Greek oral tradition near the time of Homer, evoked the Muses as the narrator of Greek mythology. Witness both the invocation of the Muses and the epithet attributed to Aphrodite.

From the Heliconian Muses let us begin to sing, who hold the great and holy mount of Helicon, and dance on soft feet about the deep-blue spring and the altar of the almighty son of Cronos, and, when they have washed their tender bodies in Permessus or in the Horse’s Spring or Olmeius, make their fair, lovely dances upon highest Helicon and move with vigorous feet. Thence they arise and go abroad by night, veiled in thick mist, and utter their song with lovely voice, praising Zeus the aegis-holder, and queenly Hera of Argos who walks on golden sandals, and the daughter of Zeus the aegis-holder bright-eyed Athena, and Phoebus Apollo, and Artemis who delights in arrows, and Poseidon the earth holder who shakes the earth, and revered Themis, and quick-glancing Aphrodite. OER Hesiod’s Theogony

Topics relevant to twenty-first century sustainable goals from the epic like those outlined by the United Nations (UNSDG) include Life on land and below water, gender equality, reducing inequality, sustainable communities and cities, quality education and peace and justice.

Sankore Mosque 1100s (left), Mali Sculpture, Mansa Musa Mali Ruler, & Djenné Mosque, 1200s (right)

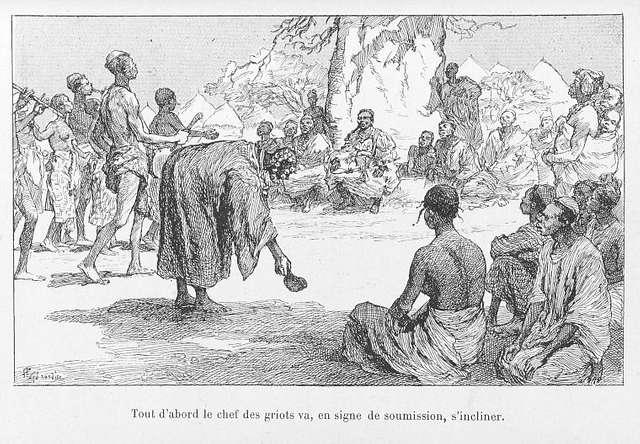

On the Epic of Sundiata by the Malinke

If you currently reside on the African continent, you are most likely familiar with the oral traditions performed to this day but rooted in thousands of years of history. And for those of you who are from West Africa, you’d also know the tradition of the djeli – the multigenerational storytellers known to Westerners as ‘griots’, a term coined by French colonists. Like other oral traditions, the stories by the Malinke, the Mali of West Africa, are memorized and performed in ritual and festivals by djelis, along with musical accompaniment. Djelis play an important role in their society and culture and serve in many of its facets – as historians and political advisors, in addition to sustaining the oral tradition. Yet, this epic does not practice what is known in Greek myth as in medias res. Events in Epic of Sundiata operate within the ideology of the Malinke culture; historical events happen simultaneously; the past, future, and present occur all in the same space of time. This can be witnessed by its hero’s affiliations with both Islam and Alexander the Great.

I am going to talk of Sundiata, Manding Diara, Lion of Mali, Sogolon Djata, son of Sogolon, Nare Maghan Djata, son of Naré Maghan, Sogo Sogo Simbon Salaba, hero of many names. I am going to tell you of Sundiata, he whose exploits will astonish men for a long time yet. He was great among kings; he was peerless among men; he was beloved of God because he was the last of the great conquerors. Right at the beginning then, Mali was a province of the Bambara kings; those who are today called Mandingo, inhabitants of Mali, are not Indigenous; they come from the East. Bilali Bounama, ancestor of the Keitas, was the faithful servant of the Prophet Muhammad.

The Epic of Sundiata is the only epic known today that has been continually retold since the 1200s. Or, if you are like me and reside in the U.S. with roots in the Americas and Europe, then you may have enjoyed aspects of the Malinke epic in popular films and theatrical productions like Disney’s The Lion King.

The Epic of Sundiata emerged from the Mali people whose storytelling culture has witnessed the history and changing dynamics of the region, including its empire building era in the 1200s and Islamic influences. “Sundiata retells the rise of a historical figure and narrates on the quest of a hero who matured and reached the status of a peoples’ king who ruled and consolidated to unite the region of West Africa and established an empire to last over four-hundred years.”Unlike epics of ancient times, Sundiata retells the rise of a historical figure and narrates on the quest of a hero who matured and reached the status of a peoples’ king who ruled and consolidated to unite the region of West Africa and established an empire to last over four-hundred years. To experience the role of music in storytelling traditions of West Africa, view and listen to musician Kadialy Kouyate, a great example of the richness of world music and the storytelling cultures of the West African people.

W. African Mali Epic of Sundiata ritual is recited by djeli (1894 engraving) and inspires adaptations, like The Lion King CC

Stories are often concerned with safeguarding families and building social ties, and Sundiata is a great example of these domestic representations. The epic inspires readers to inquire about their own origins and the journeys of their ancestors. Other archetypal quest narratives of Theseus, Jason, and Odysseus.

How Does the Maya The Popol Vuh Reflect Aspects of the Epic?

Popol Vuh’s Twin heroes (left), Athena and Jason on Greek pottery (middle), and Roman Romulus and Remus (right) CC

Let’s proceed to work through the Popol Vuh. Review key features of the epic, then work on:

- The twin heroes, on their journey to the underworld to restore order.

- Begin to observe the characterizations of the twin heroes.

- Keep track of their associations with immorality and morality.

- And as a comparative investigation, close read how the life cycle is intertwined.

- Make inquiries on how topics of sustainability enrich initial understandings of epics.

Topics relevant to twenty-first century sustainable goals from the Maya like those outlined by the United Nations (UNSDG), include Life on land and below water, gender equality, and from the Malinke sustainable communities and cities, quality education and peace and justice.

Key Points

- On the Epic and Hero’s Journey

- On the Epithets of an Epic and Literary Tropes

- On the Ideology that the epic reveals through its religious doctrine and world views

- On the Mesopotamian Epic of Gilgamesh and the Mali of West Africa Sundiata

- On the Popol Vuh by the Maya and Ecocritical readings of representations of nature in epics

Engage in Writing Assignments on the Epic & Compare Traditions

Activity: The Epic as an Informant on Sustainability

GOAL: To identify fauna and flora in the epic to read literal and its symbolism. This short writing activity builds on critical reading and thinking skills to succeed in the learning process of interpreting a piece of literature with theoretical approaches.

INSTRUCTIONS: 1) Work with The Popol Vuh, 2) Close read the passage below, and 3) Respond to the criticism on how the passage addresses aspects of the environment, 4) Apply the interpretative lens of cultural studies and ecocriticism to express your understanding of the role of agriculture to the first humans in the creation mythological story by the Maya. What do you learn? What are your inquiries?

“The making, the modeling of our first mother-father, with yellow corn, white corn alone for the flesh, food alone for the human legs and arms, for our first fathers, the four humans works. It was staples alone that made up their flesh.” OER Popol Vuh

Media Attributions

- Goddess as protector © Wikipedia is licensed under a CC0 (Creative Commons Zero) license

- Parque de Balboa © Wikipedia is licensed under a CC0 (Creative Commons Zero) license

- Venus (Aphrodite) © Wellcome Collection is licensed under a Public Domain license

- Presentation of Captives to a Maya Ruler © Wikipedia is licensed under a CC0 (Creative Commons Zero) license

- Warrior on horse © World History Encyclopedia is licensed under a Public Domain license

- Bodh Gaya © Wikipedia is licensed under a CC0 (Creative Commons Zero) license

- Maya Tree of life © Wikipedia is licensed under a CC0 (Creative Commons Zero) license

- Christian Tree of life symbol © Open Library is licensed under a CC0 (Creative Commons Zero) license

- Sankore Mosque, Timbuktu © World History Encyclopedia is licensed under a Public Domain license

- Female Figure from Mali

- Mansa Musa © World History Encyclopedia is licensed under a Public Domain license

- Great Mosque, Djenne, Mali © World History Encyclopedia is licensed under a Public Domain license

- Map of Western Africa in the 1200s © Wikipedia is licensed under a CC0 (Creative Commons Zero) license

- Storytelling in Western region © New York Public Library is licensed under a Public Domain license

- Tusk Woman at Festival © Wikipedia is licensed under a CC0 (Creative Commons Zero) license

- Hero Twins © Wikipedia is licensed under a CC0 (Creative Commons Zero) license

- Athena’s aegis, with Gorgon © Wikipedia is licensed under a CC0 (Creative Commons Zero) license

- Santa Maria della Scalla © Wikipedia is licensed under a CC0 (Creative Commons Zero) license

An epic originates from oral tradition, in contrast to the literary epic, and many are written in poetry. With an overarching narrative of several tales woven together, the topics and themes of an epic range from the origins of the cosmos, emergence of life and humanity, and heroes’ journey toward order. Epics were originally sung and performed annually, or a chosen part at a specific season. They relate narratives about people’s geographic sense of home via its plot and characters. Epics may also relate the founding of civilizations and empires. We have many of these epics today because they were eventually written down, like India’s Ramayana and the Mahabharata written in Sanskrit, Spain’s first written epic is El Cid (1100 AC) written in old Spanish, England’s is Beowulf (1000 AC) written in Old English, and France’s is Song of Roland (1000 AD) written in old French, while the Maya Popol Vuh comes in written hieroglyph storyboards and the epic of Sundiata is still orally performed every year in North Africa. Well-known epics include those by Native Americans — the Haudenosaunee Confederation, the Cherokee, the Sumerian’s The Epic of Gilgamesh, Greek’s The Iliad, English Beowulf, N. Africa Sundiata, and the Mayans Popol Vuh. The Creation by the Haudenosaunee (People Who Build A House), a confederation of Indigenous communities included the Mohawk, Oneida, Onondaga, Cayuga, and Seneca, whose territory covered a vast region from the eastern part of North American (what today is known as eastern New England seaboard) to Ohio and northward at Canada’s Lake Ontario.

culture is a multi-dimensional construct of social cohesion defined by English anthropologist Edward Taylor in 1871 as learned behavior, which contrasts colonial, essentialist, and race-ignorant views of culture as ‘biological traits’ (OER). Visit Key Terms for more details.

Oral tradition involves performing somatic and linguistic cultural codes as a dynamic visual art. These performances involve dancers dressed in sacred clothing with symbolic significances, along with music and dynamic jestering. A social group’s oral tradition is maintained and related through memory and referential communication to make meaning. Social groups communicate their people’s legacies of known institutions for the present generations to learn from and preserve. Oral tradition as performance addresses known understandings of astronomical, cosmic phenomena, biology of fauna and flora, especially about their medicinal and nutritional properties, refer to geographic locations and seasonal phenomena, relate political history and treaties, reflect on philosophical and religious storytelling traditions, and perform rituals on current technologies. Scholars like John Miles Foley point out that once an orally delivered text is written down, its original version has been “reduced,” of a once-living experience to one of bureaucracy, forever eliminating much of its meaning. Oral traditions dwarf written literature in both size and diversity (Foley Native American Oral Traditions).

The theme of a narrative or a play is the general idea or underlying message that the writer wants to expose. In Elizabethan Theater, “John Milton states as explicit theme of Paradise Lost to 'assert Eternal Providence,/And justify the ways of God to men.' Some critics have claimed that all nontrivial works of literature, including lyrical poems, involve an implicit theme which is embodied and dramatizes in the evolving meanings and imagery” (OER Elizabethan Theater). Whether you define it as the overarching subject matter of a text or its message, identifying themes in literary studies establishes initial skills in describing, summarizing, and offering a commentary to a piece of literature, without additional theoretical approaches. Yet, some research is helpful - of its historical era, culture, and geographic region.

The concept of nature is a social construct with qualifiers that make nature idyllic, or ‘balanced.’ Yet, in non-Western literary traditions, references to nature reflect real lived experiences, immersed in nature. For example, in Indigenous oral traditions, nature is dynamic. Adamson explains, “They tell of wars, crisis, and famine…they learned to live with ambiguities, to see the patterns, and to mimic natural processes in the cultivation of their gardens” (Adamson 56). Ecocritics and environmental humanists, among other scholars, witness humans as also a social construct in opposition to nature, or the nonhuman, which is witnessed throughout literature. Instances of the feminization of nature are understood as gendered ethnocentric views of nature by those who define humanity as superior to nature, and the masculine gender as superior to the female gender. These social constructions suggest anxieties about what it means to be human and overlap with discourses on power and colonialism when the colonized are effeminate, along with the conquered landscape. The gendering of a people and nature acts as a mechanism that initiated modernity, inequalities ecofeminist Soper addresses, “given the widely perceived parallels between the oppression of women and the destruction of nature” (Soper 1995). Feminist philosopher Kate Soper also argues on how nature is an ‘otherness’ in What is Nature: Culture, Politics, and the Non-Human (1995) to focus on Western attitudes from two schools of thought, on ecology and cultural criticism - that of our current climate crisis and efforts to address this crisis while understanding “the politics of the idea of nature,” on the semiotics of ‘nature’. Intersections between perception of nature and theories of sexuality offer insights into ‘the politics of the idea of nature.’

A literary trope is a recognizable plot element, theme, or visual cue that has figurative meaning. It can appear within the body of an author’s work, within a tradition, and across cultures as witnessed in world literature and world mythology. A common literary trope is the hero’s journey, which is a plot structure found in stories all around the world. Many literary tropes may not be universally understood, but occur commonly within a specific tradition – like in gothic and fantasy literature, and also in popular comics. Another recognizable literary trope that is observed in Western letters is the symbolism of skulls, like the skull Shakespeare’s Hamlet holds when he delivers his “Alas poor Yorick” soliloquy. In this scene, the skull represents a contemplation of one’s morality in the face of contradicting desires. Yet, as a religious Catholic trope a skull is associated with Jesus of Nazareth, for example. This association may signify more directly with death. Yet, in most religious contexts, skulls are associated with the life-cycle. For example, a skull in Mexican cultural traditions represents this meaning, through rituals associated with the Day of the Dead. They involve visiting and speaking with the deceased at nearby cemeteries, among other rituals; here, the skull signifies the life-cycle. The skull may also share associations with the serpent, like in Chinese and Mesoamerican traditions. Yet, the ‘serpent’ in most Western texts –the New Testament, Ovid’s Medusa, and even popular texts like Harry Potter – is usually associated with demons and the unholy, a finite view of the life-cycle. Another literary trope common in European literary texts is the color ‘white’. In many instances this color means death when associated with snow. Witnessed in James Joyce’s 1914 story “The Dead” from Dubliners, snow is a metaphor that signifies the death of a beloved and of a marriage (Wiki on Joyce's "The Dead" from Dubliners).

Over five thousand years of writing cultures have been identified all around the world and the efforts conducted by numerous scholars in literary history, among other fields like cultural anthropology, aim to understand our history of writing. A literary historian will work with a social group’s writing culture to understand its trends, including of its local, regional, and geographic influences. In literary history, scholars learn about the origins and development of a literary tradition that may include a culture’s reliance on form, style, and expressions including on drama, hymns and poetry, as well as the epic. As a part of literary studies, literary history reflects efforts to capture the historical trends of writing surrounding a specific literary tradition, like of the Indigenous community the Haudenosaunee of North America or the corpus of an author’s work, like the work of Miguel de Cervantes of Spain. Literary history also looks into historical eras, such as medieval Europe, Harlem Renaissance, and Postmodernism. For information on literary movements, visit OER Pressbooks.

The oldest known preserved book written in cuneiform. Its main hero Gilgamesh is part human and part divine. The god Anu creates Enkidu to temper Gilgamesh’s rule and dominance. Enkidu is closely associated with the wilderness; the uncivilized. Its language is Akkadian, ancient Sumerian, one of several Semitic languages.

In world mythology, an account of the beginning of the universe, solar system, and earth in both Easter, Western, and oral traditions throughout the Americas, including by the Maya in the Popol Vuh, is known as cosmogony.

An epithet is a memorable phrase associating a character in mythology with his, her, their heroic characteristics, like Mesopotamian Ninsun as the “lady of wild cows” and Greek god Achilles as “behind those protecting,” Poseidon as “Earthshaker,” and Aphrodite as “the foam-born goddess.” “Ox-eyed queen” is an epithet for Greek goddess Hera. The ‘fixed’ epithet is also used for metrical value as an ornamental and distinctive. A word that is repeated in a literary work and is closely associated with a character’s traits - via the narrator or by another character in the same text - like Dante being referred to as ‘Oh my son’ by his poetry teacher in Divine Comedy, who resides in hell.

A symbol is an object, expression or event that represents an idea beyond itself. The weather and light/darkness will often have a symbolic meaning. Survey of Native American Literature: Symbols in Literature

In Shakespeare’s drama, “Characterization is the fundamental and lasting element in the greatness of any dramatic work.” Characterization is the exhibition of passions, motives, feelings in their growth, engagements and conflicts. Dialogue becomes an essential adjunct to action. The principal function of dialogue is characterization.” Also, “Soliloquy and asides are dramatist's means of taking us down into the hidden recesses of a person's nature, and of revealing those springs of conduct which ordinary dialogue provides him with no adequate opportunity to disclose.”

Environmental ethics in Western thought understands anthropocentrism as a belief in a human-centered cosmogony and worldview that displaces the non-human for the benefit of humans, since oppressive dimensions of scientific rationalism stemming from Enlightenment humanism upon the natural realm and continues as postmodern writer Philip K. Dick addresses (OER definition & OER on climate). In addition to the exploitation of nature, the nonhuman, ecofeminist and philosopher Kate Soper argues that the legacy of a human-centered worldview has also resulted in “ethnocentric and imperializing suppression of cultural differences” (Comparing human and non-human perspectives & intersections with Earth Science OER).

Feminism explores the representation of sex and gender identities to learn how they challenge expectations, social norms, and expressions of oppressive power dynamics. Feminist criticism also explores the representation of women to build on Gender and Queers Studies, as a part of feminism as an interpretative method. For more information, visit (OER Pressbooks).

Literary theory involves philosophy and schools of thought to understand literature. As a systematic account of the nature of literature, literary theory offers approaches to literature from a particular set of principles. These principles involve a “body of ideas and methods we use in the practice of reading literature. Not the meaning, but the theories that reveal what literature can mean'' (Literary Theory | Internet Encyclopedia of Philosophy). It is literary theory that gives us approaches on how authors and their texts relate – on the significance of class, gender, race, etc. – and from standpoints that include biographical information on an author and the text or on the linguistic and unintended aspects of a text. Hence, literary theory provides the ‘tools’ necessary to understand literature in depth. Literary theorists can trace the histories of texts to understand genre formations and to view literature as a collective, rather than as an individual cultural artifact. For example, Joni Adamson provides literary theory, cultural studies, and ethnic studies to offer ecocritical scholarship on Indigenous literature to address their sustainable storytelling traditions. Literary critics apply literary theory to a text or to a literary tradition. Literary critics rely on literary theory to understand literature. This relationship may cause some confusion between literary criticism and literary theory. Just remember that the purpose of literary theory is not to determine a causal sequence, but to engage in analyzing the corpus of an individual author or poet through a theory, like ecocriticism, feminism, or Marxism.

According to ecocritic Lawrence Buell’s definition of ecocriticism, which involves the philosophical view that “human being and human consciousness are thought to be grounded in intimate interdependence with the nonhuman living world,” this “interdependence” is the web of life (Buell 2011). According to Danel Wildcat and Dine Deloria Jr. – whose son is currently History faculty at Harvard Dr. Philip Deloria (wiki on Philip Deloria), the worldview, the metaphysics of Indigenous peoples in North America experience reality as ‘related,’ the world is unified, and all aspects have significance and share a commonality among the tangible, spiritual, intelligent, and intangible. “The teachings of the tribe are almost always more complete, but they are oriented toward a far greater understanding of reality than is scientific knowledge”(OER Pressbooks on Indigenous Education, go to Ch. 9). As a more thorough and intuitive philosophy, they expose the limitations and exclusionary culture of Western culture and its reliance on Cartesian dualistic philosophy: “We live in an industrial, technological world in which a knowledge of science is often the key to employment, and in many cases is essential to understanding how the larger society views and uses the natural world, including, unfortunately, people and animals.”

Meaning in literary studies represents the critical reading and thinking vigor that interpretating pieces of literary works entail, which follow a certain literary theory or school of thought like Marxism, feminism, ecocriticism, and formalism. Visit Key Terms for more details.

The plot is the structure and order of actions and conflict in a narrative text or a play: “Freytag suggests a pyramidal model. We pass through exposition, initial incident, growth of action to its crisis, crisis or a turning point, the resolution and catastrophe. The exposition should be brief and clear. With the initial incident we enter upon the real business of the play. The play of motive should be distinctly shown. Proper relation between character and action maintained” (OER On Elizabethan Theater). The plot mythos according to Aristotle - in a play or story is presented by events and the actions of its principle characters, which also achieve artistic and emotional effects.

Common contemporary usage of the word “myth” means something which is a popular claim, but is not true. In Literary Studies, mythology – like origin stories – refers to epics from oral traditions; a few examples include Sumerian Epic of Gilgamesh, The Iliad, and the Mayan Popol Vuh. Mythology originates from shorter stories, as in fable-like stories and legends and folktales, that were later compiled to create a cohesive narrative. Ancient mythology is intricately part of a social group’s religious cult. Part of folklore, mythology is a storytelling tradition tied to religious doctrine. All of the world’s mythology was polytheistic, as witnessed in Greece, Roman, and Norse mythology, and may have changed, like the Torah, in Christian bibles, and the Quran. Mythology is sustained by its culture and their community’s oral and practicing rituals and religious tradition. Stories on creation, key creators as gods, and supernatural beings are represented throughout world mythology. At times, humans and deities coexist, which is also a major trope in mythology. For more information, visit OER Pressbooks on World Mythology.

The hero’s journey is thoroughly examined in The Hero with a Thousand Faces (1949) by Joseph Campbell. Campbell examines the literary trope of the epic hero throughout world mythology. Visit Key Terms for more details.

A formal academic discipline, Literary Studies seeks to understand literature in its totality through its disciplinary subsets like literary history, literary criticism, literary theory, schools of thought, and multidisciplinary scholarship like Gender Studies, Cultural Studies, and Film Studies. As an academic discipline, engagements in Literary Studies always look into language usage in literary history and literary traditions. “Literary Studies is concerned with the ways that language is used. If it isn’t concerned with language use, it isn’t Literary Studies. Literary Studies is about the ways in which writers use the formal resources of literature to represent and comment upon life” (Aphorisms on Literary Studies). A Literary Studies course with an ecocritical interpretative approach aims to learn from different disciplines and various literary traditions. Its purpose is to expand traditional literary inquiries in order to articulate more concrete understandings of the human-nature binary, environmental challenges, and social justice. These intersections allow learners to identify representations of nature to investigate cultural norms practiced and become informed on the role of ideology in storytelling traditions. Storytelling traditions include various branches of Literary Studies, including on the literary traditions of Indigenous communities, American Studies, Black Studies, Comparative Literature, English Studies, Ethnic Studies, and World literature. The combination of literary traditions in literary studies enhances learning experiences that both inform and challenge learners and educators alike to address themes associated with sustainability, like those proposed in the United Nations’ Sustainable Guide (UN's Guidelines). “The end of literary studies is a discussion of how literary writers use formal rhetorical devices to represent life, thereby giving us new ways to understand and experience our world…the end of literary studies is not, for example, the recognition that Milton used blank verse in Paradise Lost. The end of literary studies is a discussion of how Milton used blank verse in Paradise Lost to associate the Christian empire he represented with the English nation” (Aphorisms on Literary Studies). This approach to literary studies aims to enhance collaborative engagement by its coursework, lesson plans, and group projects that contribute to our viable futures.

In the most general sense, identity is the sense of oneself, the known self. But in literary studies, identity is quite complex since this word represents a conglomerate of many lived experiences with communities that share social norms and ideologies that contribute to the totality of selfhood, one’s own identity. For more information, visit OER Pressbooks on Identity and Literature.

(“eco” in Greek is household, ecology is the learning of the life of populations)

What is ecocriticism? At first sight, it is simply a literary theory to learn about nature in literature; when critics approach literature to learn about nature, they are offering ‘ecocritical’ interpretations. Ecocriticism aims to not reduce nature into a concept or social construct, which the Western tradition shows in the majority of its literary traditions. Literary studies offers a platform to learn about representations of nature in texts, while analyzing themes on social injustices, which may share similar treatments, since “ecocriticism is a theory that seeks to relate literary works to the natural environment” (Estok 2005). Another explanation is “the study of the relationship between literature and the physical environment” and “takes an earth-centered approach to literary studies” (Glotfelty and Fromm 1996). Another explains that, “Ecocriticism examines the representation of and relationships between the biophysical environment and texts, predominantly through ecological theory” (Chisty 2021). Since the 2000s, ecocriticism has relied on scientific and philosophical approaches to understand humanity’s place in the world. The UNSDG offer a wide-ranging view of aspects of human’s roles to address current injustices and the climate crisis. Partly, it is “committed to effecting change by analyzing the function – thematic, artistic, social, historical, ideological, theoretical, or otherwise – of the natural environment.” Ecocritical readings on environmental injustices can intersect with social injustices, like Langston Hughes’ poem expresses. *Go to the section on Langston Hughes’ poem A Dream Deferred in the introduction of this book. This class supports intersections between social injustices and environmental ones. The work of Joni Adamson, American Indian Literature, Environmental Justice, and Ecocriticism: The Middle Place (2001) features the literatures of Indigenous communities and literary analyses with ecocritical understandings to address and expose Western abuse of nature and the causes of our current environmental crises, while demonstrating the literary and storytelling traditions of Indigenous communities as ‘an alternative’ theory. For more information, visit OER on Ecocriticism. This literary theory stems from the first wave of environmentalism in the U.S. by ecofeminism. The term ecocriticism emerged in the article Literature and Ecology (1978) by William Rueckert and an earlier work in 1972 by William Meeker The Comedy of Survival: Studies in Literary Ecology. “First wave" environmental criticism concerns itself with conventional nature writing and conservation-oriented environmentalism, which traces its origins to the work of Ralph Waldo Emerson, Henry David Thoreau, and John Muir. "Second wave" environmental criticism redefines the environment in terms of the seventeen Principles of Environmental Justice and increasingly concerns itself with "issues of environmental welfare and equity" and "critique of the demographic homogeneity of traditional environmental movements and academic environmental studies” (17 Principles of Environmental Justice). A modern third wave of ecocriticism recognizes ethnic and national particularities and yet transcends ethnic and national boundaries; this third wave explores all facets of human experience from an environmental viewpoint” (Adamson 2009). Originally, ecocritics looked at the relationship between literature and nature – between culture and the global environment. Literature shows human tendencies to anthropomorphize nature. Ecocritics see culture as hierarchical and in contrast to nature, especially in Western texts. To analyze this relationship, nature needs to be distinct from human constructs: the wilderness, scenic sublime, countryside, and domestic picturesque. Man-made factors are social orders and political constructs like culture and poverty. Yet, the ‘setting’ of narratives may also be fantastic – as in folklore, the gothic, and science fiction, and hence is also fertile soil for ecocritical readings. Ecocriticism takes as its subject the interconnections between nature and culture, specifically the cultural artifacts of language and literature. As a critical stance, “it has one foot in literature and the other on land; as a theoretical discourse, it negotiates between the human and the nonhuman" (Glotfelty and Fromm qtd. in Sandner 2000). The roots of the environmental movement can be traced back to the abolition movement, which revealed the connections between colonization, conquest, slavery, resource exploitation, and capital, and many of the most successful strategies of early environmentalism were borrowed from the abolition, civil rights, and women's movements and American Indian Land Claims lawsuits. For this reason, “any history of environmentalism that did not include W. E. B. Du Bois, Rosa Parks, Martin Luther King, Jr., or Cesar Chavez, among others, would need to be revised” (Adamson 2009).

In literary works from the Western tradition, the definition of ‘human’ contrasts with nature, the nonhuman, due to Cartesian dualistic ideology. Yet, through multidisciplinary collaborations on climate, like between Anthropology, Environmental Studies, and World Literature, for example, inquiries about defining humans emerge. For example, Literary Studies and ecocritic scholar Lawrence Buell in Keywords for Environmental Studies (2013) inquires about such definitions in light of twenty-first century climate and sustainability challenges to “point to critical questions that must be asked and answered with regard to what it means to be ‘human’ and what it means to be in the multispecies relationships within the biosphere” (Buell qtd. in Keywords for Environmental Studies). Humans in contemporary scholarship should not be confused with posthuman in science fiction and transhumanism.

In Latin in medias res means “in the middle of things.” Some epic narratives start ‘in the middle’ of its plot; hence, it starts in medias res.

Coined by Klaus Schwab of the World Economic Forum, our current historical moment since the early 2000s is designated as the Fourth Industrial Revolution and has become widely known since his 2016 publication. The Fourth Industrial Revolution navigates online technologies throughout major sects of society at a global scale – commercial, communication, education, manufacturing and production, and consumption. New technologies have not only transformed these traditional sects, but has also made them dependent upon them. “The concept of the Fourth Industrial Revolution affirms that technological change is a driver of transformation relevant to all industries and parts of society” (Columbia University). For more information, visit OER on The Fourth Industrial Revolution.

How and when information is presented. For example, to understand a historical fact – like African slavery in the Americans – it is important to know its context. Context means any background information that contributes to African slavery in the Americas. The context can address 1526 when the Spanish took Africans to Georgia and S. Carolina, or 1619 when the English brought African slaves, or even 1440, when the Portuguese first brought Africans to Europe. Hence to understand African slavery in the Americas we should research its context. This also includes the 800-year history of the African Moors in Europe. Starting in 711 C.E.

A concept that encompasses the dynamic and intricate network of how humanity affects communities, the environment, and climate. Current efforts to address a wide array of cultural and sociological practices that are all interrelated and connected to seriously address the causes and effects of ‘climate instability’ and other injustices that plague some societies while threatening the rest. The United Nations offers 17 goals of development to highlight many facets of society – from the production of goods and treatment of women and the impoverished and social justice and renewable energies (UNSDG ). Yet, current scholarship by ecocritics in literature emphasizes the fundamental need to address today’s crisis – a sustainable ideology, to demystify human and nonhuman binary thinking. Where we as a global people realize that we are interconnected to local and global ecologies. This worldview can also demystify current human tendencies of placing humanity above the nonhuman. An example of this argument is witnessed in Frank Boom’s ecocritical analysis of Ovid’s Metamorphosis, Book 10 and 11, on the mythological tales of “Orpheus and Cyparissus” (OER Article on Today's Climate Crisis & Ovid's "Metamorphoses").

Whether people may recognize that the environment includes all aspects of nature – from the cosmos to the Earth’s oceans, atmosphere, and forests with all of its life-forms, from an etymological perspective, the environment has been understood from a human-centric stance. This stance is a mode of anthropocentrism. This means that the environment is inherently viewed through a human-centric lens in many traditions, especially throughout the Western tradition. “Within ecocritical discourse, it is often acknowledged that the anthropocentric views that have developed over the centuries are at the roots of the ecological crisis. To call the nonhuman bodies the “environment,” points to the human body as the center of that environment, which can in itself be considered as an anthropocentric way of envisioning the world...This period is now identified as the beginning of the Anthropocene” (Boom 10). Hence, current climate challenges and ecological crises must be understood from a more ‘neutral’ and informed stance.

Intersectionality is the “study of overlapping, intersecting social identities and related systems of oppression, domination, or discrimination” (Syracuse University). Intersectionality was first posed on Langston Hughes poetry to highlight intersections between racism and the legacy of slavery with environmental exploitation and that of Black laborers, where learners can conduct further research on such overlapping topics. For example, learners can research Black oppression in the 1840s through the work of America’s first ‘Father of Black Nationalism’ Martin R. Delany, in order to learn about the effects of slavery, while researching Joni Adamson’s work on environmental devastation. Intersectionality is a concept coined by American law expert Dr. Kimberlé Crenshaw in a 1989 paper to address the oppression of African women to address that gender and racism are not “mutually exclusive categories of experience and analysis.” In legal matters, injustices on both gender and race are considered separately in the U.S. The tendency to simplify a composite of injustices that are all related is described as interpreting the law on a ‘single axis framework’ (on its history). To remedy this oversimplification, Crenshaw coins the idea of ‘intersectionality’ as an approach that recognizes the complex composite nature of an injustice that reflects several injustices at once. Her goal is to make Black women more visible and for the law to acknowledge their plight as women of color (Sociology & Intersectionality). Intersectionality is a lens through which you can see where power comes and collides, and where it interlocks. “It’s not simply that there’s a race problem here, a gender problem here, and a class or LBGTQ problem there. Many times that framework erases what happens to people who are subject to all of these things'' (Columbia Law School).

A Greek poet as significant as Homer on the legacy of Greek mythology. He wrote the first known Farmer’s Almanac with wise sayings that Benjamin Franklin emulates in his work. Hesiod wrote poetry, on agriculture, early Greek astronomy, and economic theory. Like the Sumerian poet Enheduanna, he is the first known Greek poet who viewed his work as ‘an individual’.

In West African oral traditions of folklore, history, and politics, the tellers are called djei. They are trained in successive generations. Most of us from the West know them as ‘griots’. The djei performs and shares stories by memory in rituals and festivals.

The epic hero of the epic Sunjata, on the history of the Mali empire – one of many empires across the African continent with historical and legendary figures. Sundiata is the only known ‘living’ oral epic. Like other epics, Sundiata reflects African religious traditions. Told by their poetic ambassadors of the royalty as storytellers with the title griot. Sundiata has inspired modern-day stories like Disney’s The Lion King and Marvel Comics Black Panther.

“A more or less systematic ordering of ideas with associated doctrines, attitudes, beliefs, and symbols that together form a more or less coherent philosophy or Weltanschauung for a person, group, or sociopolitical movement” (APA Dictionary qtd. BU Equity Guide). In schools of thought such as political science and psychology, ideology is addressed as a system of beliefs that underpins and sustains the form of a society. A school may be supported by an ideology of curricular vigor that rewards certain achievers. The economy of a country may be supported by a capitalist ideology. But, ideology is also understood through other worldviews and cultural norms, like those practiced by the Indigenous communities of the Americas.

These are foundation stories whereby an exiled hero ensures quests and faces threatening antagonists to then, once proven worthy, return and help found a new civilization or replace an old ruler. Greek heroes Perseus and Jason fall into this role, as does Odysseus. In Maya mythology, the Twin Heroes Hunahpu and Xbalanque restore patriarchal order in the Popol Vuh.