Chapter Two: On Indigenous Storytelling Traditions & Sustainability

Outcomes and Skills Practiced

-

Identify context of featured storytelling traditions of Indigenous communities

-

Apply key concepts to featured creation and origin mythological stories as cosmogony

-

Textual analysis of theme, literary tropes, & ideology that intersect with sustainability

Our stories were us, what we knew, where we came

from and where we were going. They were told to remind

us of our responsibility, to instruct, and to entertain.

There were stories of the Creation, our travels, our laws.

Larry Hill, Seneca

Seneca Totem Raven, Haudenosaunee Antaensic (Sky Woman), & Transformation Mask (1865) by Nuxalk or Heiltsuk. CC

Introduction to Chapter Two

For over 20,000 years, the Indigenous communities of Mesoamerica and throughout the Western Hemisphere represent a direct link to the world’s “cradles of civilization,” of early agriculture-based societies with architectural and scientific advances during the Bronze Age of human history (OER on Geology of Hemisphere). The Incas developed a complex accounting system by 600 C.E. The only known human civilization to independently create a writing system is the Maya, who developed a writing system by 900 C.E. Mayan artisans also refined porcelain. By the 1400s, the Aztecs built pyramids comparable to the Egyptians. And, by the early 1600s, the Haudenosaunee Confederacy engaged in treaties to consolidate and expand territory.

Today, the ancestors of the Maya, Inca, Aztec, and of the descendants among many surviving global Indigenous communities – of ancient peoples from cultures comparable to Mesopotamia, China, Egypt, and the Indus Valley – continue to persist within environments known to their peoples for millennia (OER on History of Indigenous in Americas). Caribbean islanders also presently strive to persist and preserve ancient sustainable means of living throughout the West Indies, like the descendants of the Taínos and hundreds of social groups throughout Brazil (OER). While facing concerns over sustainable governance, Indigenous communities all around the world to this day, continue “using their knowledge and understanding of reciprocal relationships with the environment to demonstrate a more sustainable approach”(UN). Their concerns demonstrate twenty-first century storytelling traditions directly connected to legacies of sustainability situated both in the present and past. “As Earth’s original stewards, the lives of Indigenous peoples are rooted in sustainable development processes” (UN).

How Do Indigenous Stories Include Humanity in the Web of Life?

Outcome and Skill Practiced

Gain practice with origin stories by Indigenous communities to continue to identify key concepts anTo build textual analysis on representations of nature

Throughout the northern region of the eastern seaboard of North America, the literature of its ancient cultures has had a vast oral storytelling tradition. The Haudenosaunee Confederacy of the Mohawk, Oneida, Onondaga, Cayuga, Seneca, and the Tuscarora and the Anishnaabe are several examples of these northern Indigenous communities, whose mythological storytelling oral cultures continue in ritual and writing. Other Indigenous communities are the Cherokee, Seminole, Sauks, Navajo, Hopi, Chumash, Lakota, and Laguna Pueblo people, among many many many others who have resided in the American Midwest, the South, and Southwest for thousands of years (OER on Indigenous History of North East).

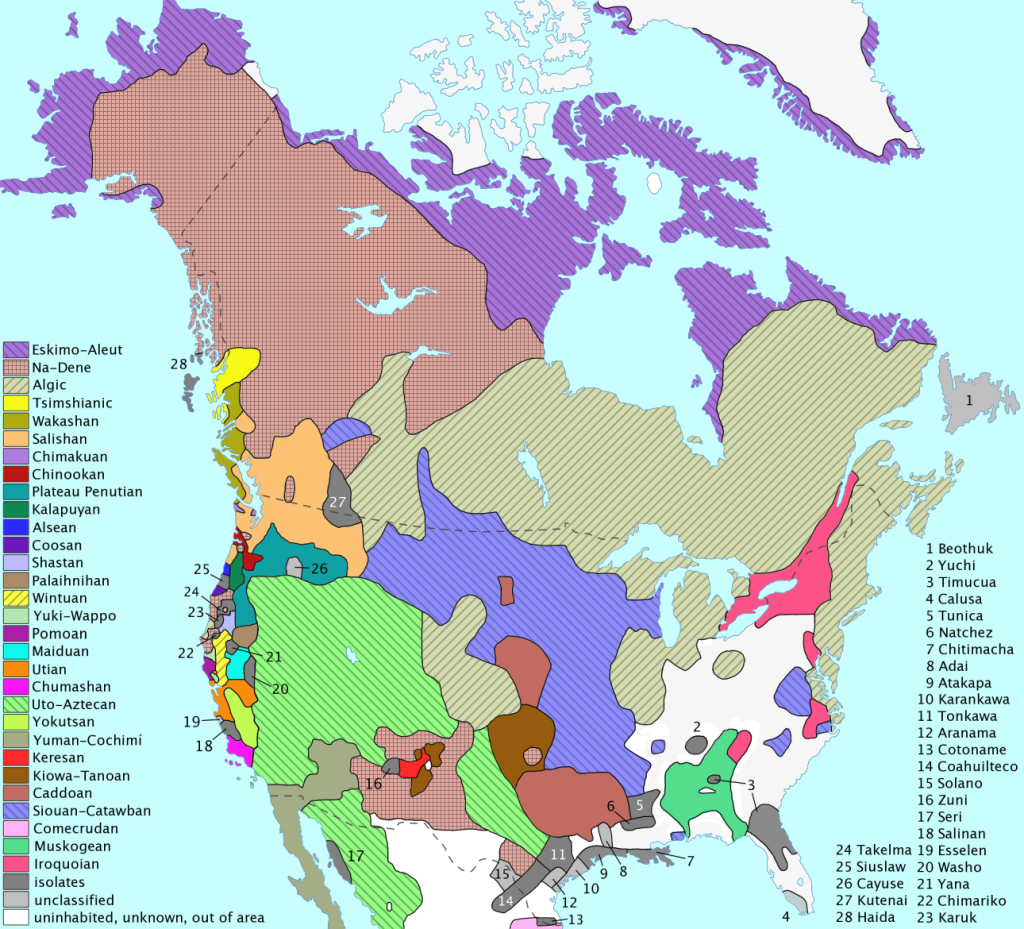

Map of the land of Indigenous communities throughout Canada, Northern Mexico, and the U.S. OER

Efforts to save, collect, and write down the knowledge and stories of Indigenous oral traditions were initiated in the early 1600s, at the advent of European colonialism and again in the 1800s, at the advent of American territorial and economic expansionism when expulsion became the norm. “Native identity was easily erased because Native peoples’ conceptions of themselves are closely tied to their conceptions of their land and their communities (Basso 1996, 67 qtd. in Michalec).” As an anthropological practice witnessed since the early 1900s by other ethnographers including Black author, dramatist, and anthropologist Zora Neale Hurston, more recent efforts to save the oral texts of Indigenous traditions gained momentum in the 1970s when members of the Indigenous communities themselves worked to preserve the knowledge of the spoken word traditions of the elders (OER on Indigenous expulsion). The work of storyteller and postcolonial scholarship and recipient of the MacArthur Laguna Puebla Leslie Marmon Silko demonstrates how this knowledge informs on current climate concerns and gender.

We, as a class, have come to the conclusion that Mary Shelley’s depiction of Victor was not as the traditional protagonist, and Le Guin wrote Don Davidson to bash the masculine hero trope, and so Silko’s views on the binary between men and women can help our own understanding of our prejudices and biases…(OER CUNY).

The oral traditions of Indigenous communities also show a sophistication of rhetorical technique and a reverence for the spoken word unheard of in modern Western storytelling culture. Pulitzer prize winner Indigenous Kiowa of the Great Plains (Oklahoma, U.S.) and scholar Navarre Scott Momaday explains the reverence Indigenous communities have for the spoken word.

Words are spoken with great care, and they are heard. They matter, and they must not be taken for granted; they must be taken seriously, and they must be remembered….At the heart of the American Indian oral tradition is a deep and unconditional belief in the efficacy of language. Words are intrinsically powerful.

The oral tradition of the Indigenous Seneca shows a reverence for the spoken word. Being the largest community of the Six Nation (Haudenosaunee) Confederacy, the oral narratives of the Seneca were written down in the twentieth century, but the collection only represents a fraction of their tradition (OER pdf of collection). “According to John Bruno Hare, ‘This huge (500 page) book of Seneca myths was collected by Jeremiah Curtin at the turn of the 20th century. Curtin also wrote Creation Myths of Primitive America, Myths and Folk-lore of Ireland, and Tales of the Fairies and of the Ghost World’” (OER on Seneca).

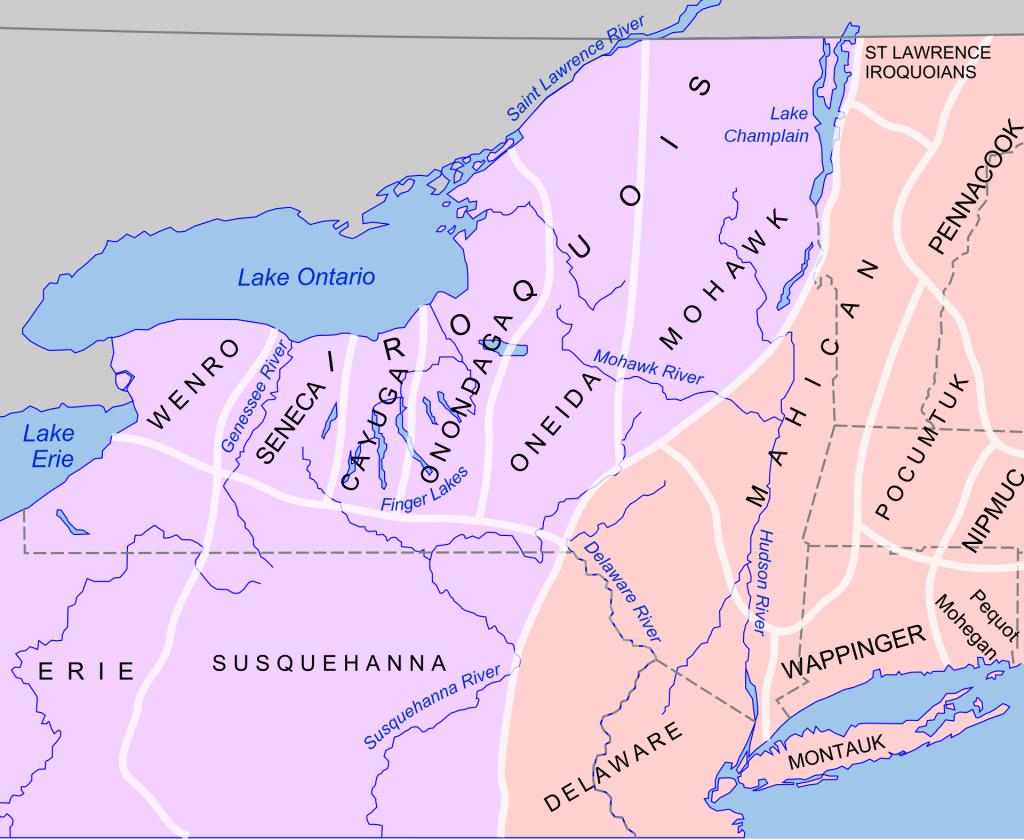

The Haudenosaunee people resided in the Northeast region of the modern United States CC

The mythology of the Seneca also demonstrates a reverence for the spoken word through a philosophy that understands humanity’s interdependence of the web of life, in that the Seneca attributes fauna and flora as contributors of their peoples’ identities and survival. In turn humans show a respect toward nature by reciprocating with an offering of tobacco, an indigenous ritual later acculturated by European colonialism (Lemire 2021). Seneca mythology asserts an intimacy with nature by relating the cosmos to all of their people, including those who endure exile.

In the Seneca mythological story The Origin of Stories the past links with the present by a spirit that emerges from the immediate geological region; a cliff. This spirit also emerges to represent an ancestor. For the Seneca, this expression of the cosmos represents an instance of anthropomorphism that does not depend on a human-centered reality, which contrasts geocentric worldviews throughout Western tradition. In this cosmogony, nature for the Seneca represents an actual known landmark that connects the present community with their past through storytelling. This treatment of the land reveals how the Seneca identify with the web of life (OER “The Origin of Stories”). For example, the hero of The Origins of Stories is Gaqka, an orphan who is forced into exile. Alone, Gaqka learns to become a storyteller when he listens to a speaking cliff that tells him stories. In return Gaqka offers the speaking cliff tobacco.

The first night he sat on the edge of the cliff. He heard a voice saying,

“Give me some tobacco.”

Looking around the boy, seeing no one, replied,

“Why should I give tobacco?”

There was no answer and the boy began to fix his arrows for the next day’s hunt. After a while the voice spoke again,

“Give me some tobacco.”

In this story, the current generation learns to honor the past through a speaking rock, whose stories link the Seneca to their oral tradition. Its philosophy of the interconnectedness of the web of life attributes nature with the past, present, and future. This philosophy grounds humanity with the elements, even while Gaqka faces a possible existential dilemma; how does one survive without a people as an exiled orphan? When the speaking cliff informs Gaqka that is his own deceased grandfather, the youth’s present dilemma dissipates. Gaqka continues to train in Seneca storytelling tradition and matures.

The ideology of the Seneca relies on negotiations and interactions among its people, nature, and the past. This is all accomplished through engaging with and honoring their surrounding; the land. Themes include how to be human through representations that acknowledge the primacy of the web of life, where relatives teach younger generations about how to engage in reciprocal relationships with nature.

Seneca mythology also shows how this Indigenous community experiences time and plans for an existence beyond survival. Like an omniscient present, the Seneca understand storytelling as a medium to establish and build a sense of place and permanence for their community. Being part of nature means humans experience change and transformation, like the cyclical phenomena throughout nature.

Origin stories in the mythologies of Indigenous communities, like those of the Seneca, advocate for and inform on what we call today sustainable communities, which is Goal Eleven in the United Nations list of Sustainable Goals (UNSDG). Efforts to address hunger and poverty are also addressed in UN Goals One and Two on sustainability.

On Identifying Literary Tropes in Mythological Emergence Stories

Outcome and Skill Practiced

Gain practice in textual analysis of a creation mythological storyTo identify and engage in close reading on key terms and literary tropes which represent nature.

Creation stories by the Indigenous communities of the Haudenosaunee known as the “People of the Longhouse” and by the Anishinaabe and the Ojibwa known as “The People Who Live upon the Earth in the Right Way” and “Spontaneous Beings” reflects literary tropes on the 1) Emergence of a new world, 2) Initial appearance of humans, 3) A miraculous birth, and 4) The hero’s journey.

For example, these literary tropes are demonstrated by Sky Woman Antaensic in the Iroquois Creation.

Sky Woman realized she was going to give birth to twins….In the center of the island there was a tree which gave light to the entire island since the sun hadn’t been created yet…Far below she could see the waters that covered the earth….She fell through the hole, tumbling towards the waters below. Water animals already existed on the earth, so far below the floating island two birds saw the Sky Woman fall. Just before she reached the waters they caught her on their backs and brought her to the other animals…The Sky Woman gave birth to twin sons.

Antaensic represents the interconnection between the cosmos, Earth, and Turtle Island, while the representation of nonhuman life forms play a central role in the creation.

This creation mythological story, as cosmogony, reveals a less hegemonic ideology. An acknowledgement of a cyclical and interconnected reality is presented in this myth where nonhuman deities, the significance of life-forms, and the role of reproduction are all located within a single physical material environment; the web of life. Expressions of anthropomorphism are also less anthropocentric.

As you begin to realize that you are building on prior knowledge and on your critical reading skills by identifying elements of fiction, key literary terms, and annotating beyond summary, you should also practice identifying emerging themes and sources of conflict. To gain more familiarity and practice with mythology, let’s turn to Taíno storytelling.

Taíno Storytelling

Outcome and Skill Practiced

Gain practice in textual analysis of a Taíno creation mythological storyTo identify and engage in close reading on key terms like symbolism and theme, which represent nature.

Like the creation mythological story by the Haudenosaunee, the creation myth by the Taíno also begins in a place before humans emerged. A journey also takes place by parentless brothers – the common literary trope of ‘orphan stories’ manifests in this cosmogony, too (https://youtu.be/arlTwhiMxVM).

In the Taíno’s creation story the elders tell stories about the mother of the brothers, about the fertility goddess Cahubaba. She died giving birth to them, just like Antaensic Sky Woman in the early Indigenous creation story by the Haudenosaunee – another common literary trope. The role and the plight of the god Deminan in the Taíno creation story shows a desire to establish a link between the cosmos and the earth in order for humans to emerge.

This Taíno mythological creation story becomes much more complex once its symbolic and cultural worldviews are investigated. The idea of water as a source of creating new lands and seas is one example of an aspect of the story that can be understood symbolically. Also, the transformation (shapeshifting) that Deminan experiences is another example where symbolism can be investigated to learn more about the ideology behind this story and of the culture of the Taínos

In early mythology and in more developed narratives like the epic, we are also challenged to learn about the plot and its characters in terms of symbolism. To develop understandings beyond literal ones of this Taíno story, go to recommended sources at the end of this chapter.

Topics relevant to twenty-first century sustainable goals from Diné Lyla June, the Haudenosaunee, and the Taíno like those outlined by the United Nations (UNSDG), include Life on land and below water, gender equality, reducing inequality, sustainable communities and cities, quality education and peace and justice.

How Do Storytelling Traditions Vary in Indigenous Communities?

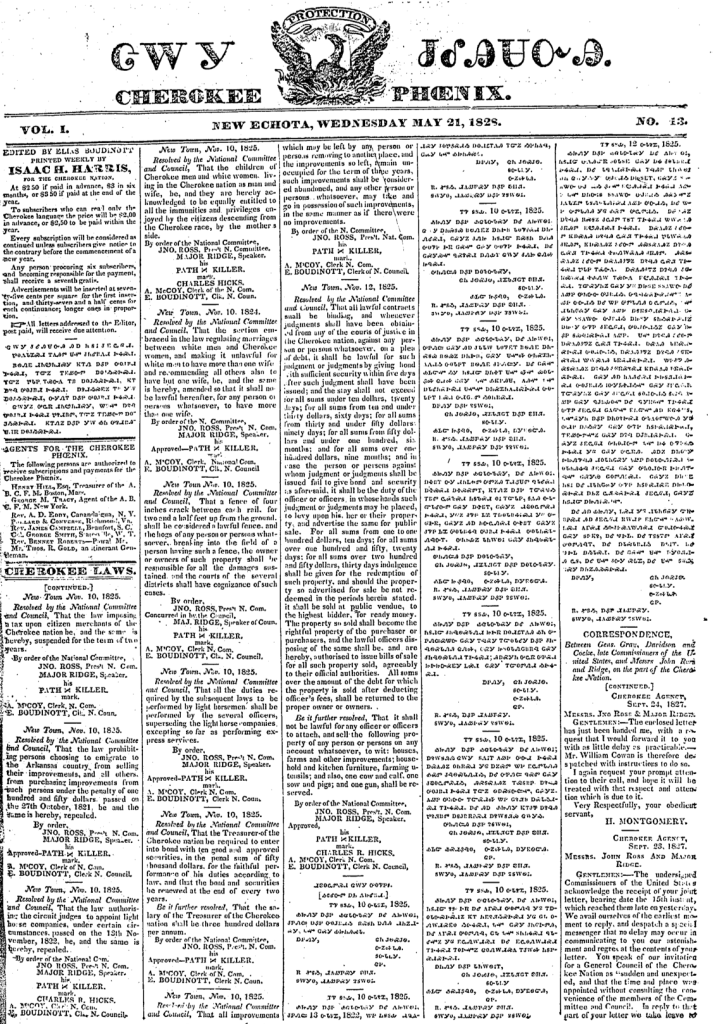

Jane Schoolcraft (left), 1828 Cherokee/English Newspaper, Leather Anishinaabe artisan shoulder-bag 1820 CC

Those of us who are not part of an Indigenous community are challenged by their storytelling traditions. Many members of these communities have and continue to live closer to nature and their stories reflect this relation to their environment. A sampling of their mythological stories began to be told and published by tribe members, especially those who married people from other cultures and languages from Europe. In the United States Anishinaabe-British Jane Schoolcraft and Cherokee-Irish John Rollin Ridge became prominent bilingual authors by the mid-1800s.

“Many members also suffered injustices that caused cycles of trauma due to ‘reeducation’ programs of the early 1900s. ‘It was during the Indian Wars that the US Cavalry rounded up the Natives, successfully homogenized them into Indian Country, and put them in boarding schools to take away their spirit’. To work with their literary works means to also learn about their value systems” (Nez 2011).

By 1820, the Cherokee Sequoyah became the first member of an Indigenous community in North America to create a writing system. His efforts demonstrate the intellectual superiority of the Indigenous communities, as well as their social agility to interact with different cultures and adopt technologies. Sequoyah’s invention also shows the intellectual pursuits by many of these communities to confront colonial and imperial dominion in order to protect their culture and survive. For the Cherokee, among many other social groups whose ancestral territories are located east of the Mississippi River, their efforts directly confronted a sequence of “Indian Removal” laws, from 1828 in the U.S. These acts justified the expulsion of the Indigenous communities of the region. Although the language in these acts claimed to protect the livelihoods of the natives, its underpinning ideology was one that blatantly claimed dominion over the ancestral lands of Indigenous communities to access natural resources in demand. Mythic ideals of expansionism as mandated by Christianity were also expressed to further justify expulsion. Many members also suffered injustices that caused cycles of trauma due to ‘reeducation’ programs of the early 1900s. “It was during the Indian Wars that the US Cavalry rounded up the Natives, successfully homogenized them within Indian Country, and bordered them into boarding schools to take away their spirit” (Nez 2011). To work with their literary works means to also learn about their value systems. In many cases, it is their ideals and values that sustain their culture for future generations.

How to Navigate a Piece of Literature to Learn about Ideology?

A culture’s worldview and social order are sustained by ideology, as practiced social norms and accepted beliefs reflect it.

Let’s practice close reading approaches that are more inquisitive and objective:

- To read more objectively, try to not make assumptions, inquire instead

- To make inquiries, ask questions like, How similar are the religious doctrines of these peoples with a Buddhist or Christian worldview? Do we share values? Which ones?

- To build on critical reading approaches, also practice reading a literary work to identify the characteristics of its worldview. Ask, “What do they hold sacred?”

- To build on close reading, engage in textual analysis by identifying key passages.

Working on a culture’s ideology through their storytelling tradition also supports projects on sustainability, because ideology may aggravate sustainable aims and threaten climate stability or uphold social norms that value nature, which minimize harm to its people and the web of life overall.

Close Reading Exercise

GOAL: Build skills on the role of character and plot. This short writing activity builds on critical reading and thinking skills to succeed in the learning process of ‘interpreting’ a piece of literature with theoretical approaches.

INSTRUCTIONS: Build on Activity A. Work with mythological stories by the Haudenosaunee and Anishinaabe. Identify and explain the presentation of ‘conflict’ that pushes the plot. How is conflict, imbalance, established through characterization and plot? What exactly threatens ‘imbalance’ and chaos? Then, demonstrate in writing how the chosen mythological story restores balance. Ask, what problem-solving techniques does each story share for future generations? Add your initial reflections on how conflict in the stories assist the present generations to also address imbalance.

Refer to the quote below by ecocritic Scott Slavic on the importance of experiencing literary works that value the dynamics between the human and non-human.

“Ecocriticism without narrative is like stepping off the face of a mountain—it’s the disoriented silence of freefall, the numb, blind rasp of friction descent. To the extent that our scholarship begins with our experiences in and concern for the physical world of nature, we must seek an appropriately grounded, conscious language. The language of stories, charged with emotion and sensation, may be our best bet” (Narrative Scholarship: Storytelling in Ecocriticism 1995).

How to Navigate Works of Literature to Understand Ideology?

Outcome and Skill Practiced

Gain practice in textual analysis of Indigenous literature and oral storytelling traditions by engaging in close reading and listening skills to identify key terms on ideology, gender fluidity, and sustainability.

To identify and witness the ideology of a social group is

- To learn about their cultural worldviews through their artifacts – recorded texts and revered objects, for example. A people’s oral storytelling tradition is another form of artifact that reveals their philosophy, religious practices, and their social order.

- Other cultural artifacts and practices that reveal ideology are its social institutions – like marriage, agriculture, and food production, among others.

Learning about ideology is a fruitful path when considering problem-solving methods to address today’s challenges on sustainability, including those that pertain to climate.

Activity On Note Taking to Identify Ideology in Storytelling

GOAL: To build on textual analysis of identifications in culture, such as characteristics and trends in ideology

DIRECTIONS: Download “Why We Need Gender Fluidity” (2015) TED Talk by Indigenous Nick Metcalf, Yellow Hawk of the Rosebud Sioux tribe in South Dakota: TED Talk by Metcalf, Yellow Hawk Listen to Yellow Hawk’s Ted Talk. Listen again and write down your observation:Write down your observations on how geography is understoodWrite down your thoughts on how gender and “two spirits” are understood by the Rosebud Sioux TribeAlso, share your observations about what you learn about their ideology, especially in reference to your own community’s cultural norm. *For more info, go to OER 2016 Interview of Yellow Hawk, at UN of Minnesota

How to Compare the Ideologies of Different Traditions?

It is now common knowledge that the ideology of Western cultures can be quite hierarchical and hegemonic. This can be witnessed in the political realm and in the order of its institutions, from the religious to the secular, like education and the marketplace.

In Western cultures, the impact upon the surrounding environment follows an economically-dominated value system that coincides with the first industrial revolution in the early 1800s. Its impact is exponentially worse than older versions of urban development and has accelerated environmental destruction to alarming rates worldwide. Its cultural norm of extracting resources refuses to integrate and treat ecosystems equitably. Both people and wildlife are exploited. Understanding how hegemony operated that has resulted in rigid hierarchical social orders helps present generations to prevent and address concerns with unsustainable ideology.

For example, Lawrence Buell speculates that “[i]f, as W. E. B. Du Bois famously remarked, ‘the key problem of the twentieth century has been the problem of the color line,’ it is not at all unlikely that the twenty-first century’s most pressing problem will be the sustainability of earth’s environment” (Ybarra 2009). Yet, the social orders of non-Western cultures reflect a different, more sustainable ideology, one that is less driven by the demands and lifestyles of the industrial revolutions, and more by the rhythms of seasons and attention given to the preservation of local fauna and flora.

INTERTEXT

The poetry of Tohono O’odham Ofelia Zepeda, a professor of linguistics at the University of Arizona, addresses the aftermath of the nuclear arms race and nuclear testing in the American Southwest. In explaining the poem “Bury Me with a Band” by Zepeda, Indigenous communities and environmental humanist Joni Adamson remind us of the role nature has to its Indigenous people. “The people in Zepeda’s landscape are connected to the ‘people before them,’ the creators of the ancient petroglyphs scattered throughout the region” (Adamson 12). Zepeda’s poem “Black Top” explains how her mother desires to return to the desert earth once she passes (OER on works by Ofelia Zepeda, 2011).It wants to carry me in all directions.

It whispers, ‘You will always see Waw Giwalik

In your rearview mirror’” (Adamson 66).

(An oral history on Ofelia Zepeda and live recording at .gov Tohono O’odhan Ofelia Zepeda’s poetry)

Zepeda espouses a less abrasive ideology, one that “humans must forge a more reverent, respectful relation to the land.” Their worldview recognizes the inherent connection between life on earth, the sky that nourishes the earth and replenishes rivers and agricultural crops, and the cyclical phenomena of the cosmos: what we know as ‘the compass’, the natives see the ‘circle’ of the earth, moon, sun, and seasons, a value system that is also demonstrated through a dance ritual by Alexander [Kipochtakaw] in a 2015 Ted Talk.

TED Talk on Hoop Dance Ritual & Living in a ‘Circle’ with Nature

Representing the Cree nation near Alberta, Canada, Alexander (Kipochtakaw) presents the multiple roles of oral tradition and storytelling traditions of a hoop dance ritual. His Indigenous community represents cultures that rely on memory and the cohesion of the community to protect their stories for generations, as pre-writing societies.

Not unlike our depositories in libraries, mythological stories are now housed and handed down to future generations through complex cultural and annual events and rituals by a social group. To better understand the role of storytelling in pre-writing cultures, just ask, where do the ideas live and are preserved – through the talents and memories of its storytellers; of community members, people everyone knows.

The value of multigenerational storytelling reflects an ideology grounded in the community. Stories performed in ritual and dance are preserved for generations. These tellers are multi-generationally trained, like the West African djei or what most of us may know as griots – to perform and share stories by memory in rituals and festivals.

How do African and African Diaspora Intersect with Storytelling?

Outcome and Skill Practiced

Learn about ideological differences between Western and non-Western traditions, identify how the literary texts by African Americans and Indigenous Americans represent nature, and engage in close reading to identify key terms related to ecocriticism and intersections with sustainability.

Ecocritics have identified ideological differences of worldviews and values throughout world literature, as between Western literary tradition and the literary traditions of Indigenous communities throughout North America and those of African descent. Elaborating on Joni Adamson’s ecocriticism on the literature of the Indigenous communities of North America, Jeffrey Myers compares the ideologies of Black Americans with those from Indigenous cultures and European-Americans to distinguish sustainable worldviews, values, and treatments of nature from those that regard people and nature as inferior, with less innate worth.

“Charles W. Chestnut and Zitkala-Ša, two writers of color late in the century, imagine a more fully ecological vision of people and the land without which the environmental visions of writers like Muir, Austin, and even Thoreau remain incomplete” (Myers 2005).

This distinction is helpful for literary studies geared toward understanding “our cultural and historical differences,” as Dr. Joni Adamson asserts (American Indian Literature, Environmental Justice, and Ecocriticism 2001).

What Ecocritical Approaches are Represented by Ethnic Writers?

In a literary studies course, literature encompasses both our familiarity with its forms and styles and also with the cultural trends of its people. Cultural Studies, Black Studies, and Postcolonial Studies are just a few literary theories that acknowledge the cultures from which a literary culture represents. Once we address intersections of a literary culture with its communities and environment, interpretative approaches are eco-critically focused.

Ecocriticism serves as a navigating interpretative approach in this journey. By identifying social and environmental injustices, for example, understandings of ideology emerge to inform all learners about more sustainable worldviews.

“The more holistic relationship between humanity and other beings in the natural world characteristic of Native American and West African cosmologies subverts the dominant culture’s alienation from nature and desire for mastery over it” (Myers 2005).

Hence, ecocriticism enhances other literary approaches like Feminism and Postcolonial Studies. Our role is to learn to identify and recognize a sustainable ideology, even if we ourselves come from cultures whose ideologies view the nonhuman as inferior.

Topics relevant to twenty-first century sustainable goals from Jane Schoolcraft, John Rollin Ridge, Sequoyah, Nick Metcalf, W.E.B. Du Bois, Ofelia Zepeda, Alexander (Kipochtakaw), Charles W. Chestnutt, and Zitkala-Ša, like those outlined by the United Nations (UNSDG), include gender equality, reducing inequality, preserving life on land, quality education and peace and justice.

How Does Western Ideology Differ from Non-Western Ideology?

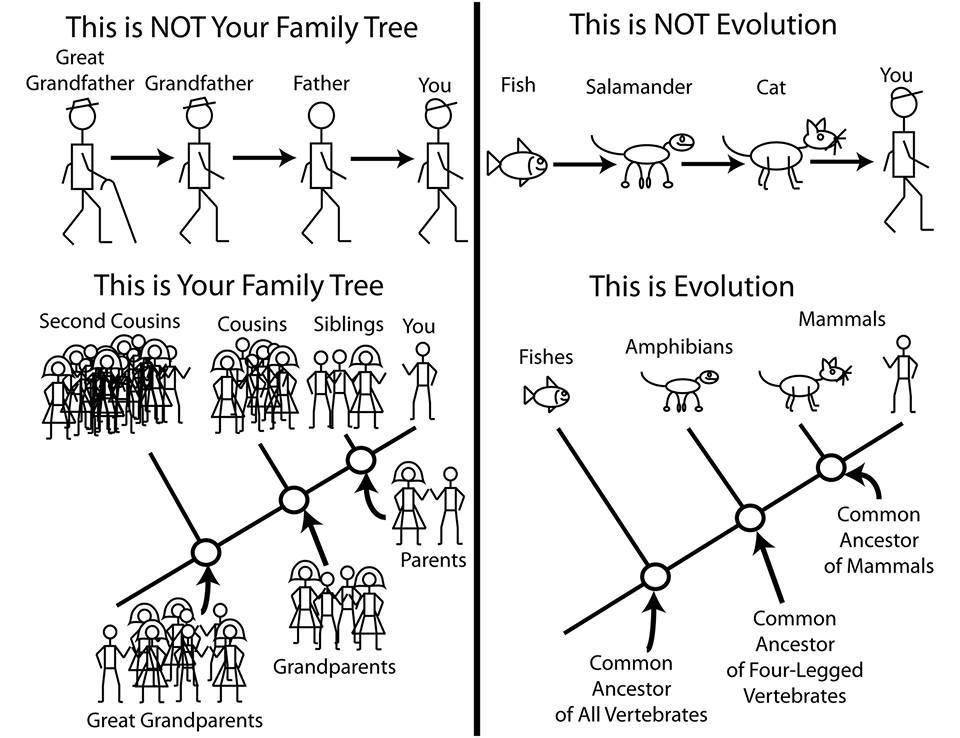

View diagram on family tree and evolution: Visual aids demonstrate differences – what are they?

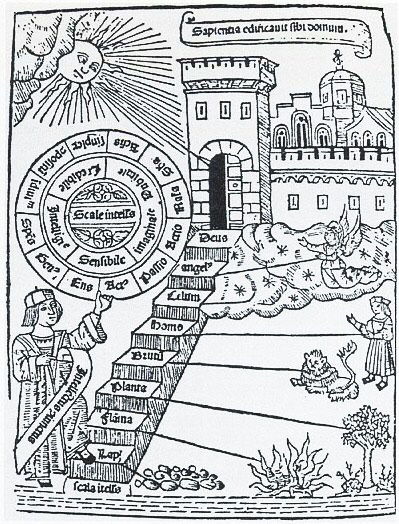

Paleontologist Bonnan’s old vs. science-based ‘the web of life’(left), Bonna’s scientific view (center), & medieval view (right) cc

Some of us may come from cultures that form the Western tradition with a Western ideology. An ideology that reflects Western values and traditions encompasses a hierarchical sense of social order, worldview of ‘the web of life’, and even of the cosmos. For example, Christianity views the ‘web of life’ as hierarchical. Yet, we may hold personal values and world views that reflect a more heterogeneous ideology, as earlier classical cultures also understood a dynamic view of life on earth.

“The idea of a continuous scale of differences between entities, as opposed to discrete classes of entities” (Egan 2011).

The ideology of the Indigenous communities of the Americas contrasts Western ideology, as Gabriel Egan suggests. Expressions of the web of life by Indigenous communities resemble the cyclical quality of the seasons, the planet, and the cosmos.

How do Indigenous Communities Explain Ideology?

The storytelling culture of the Indigenous communities throughout North America originates in oral tradition. Their creation and origin stories are quite wondrous because these early forms of narratives reflect worldviews and ideologies with values not common in the oral traditions from other geographic regions and continents.

The mythology and folklore of the Indigenous communities throughout North America are complex and integral to a culture’s sense of community, place, and memory. The form and episodic plots and characters in their mythological stories and folktales reflect aspects of the narrative known in world literature.

Two early forms of mythology are the emergent and origin stories. They establish the tribe’s ideology through episodic plots, heroes and villains and literary devices like the epithet and theme. Early mythology also addresses topics that we care about today, including aspects of sustainability, which initiate critical thinking inquiries. For example, Navajo [Diné] Indigenous Community storytelling, as is shown in Diné Lyla June 2022 TED Talk 3000-Year-Old Solutions to Modern Problems: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=eH5zJxQETl4

Diné Lyla’s presentation challenges present audiences to witness different ideologies and perspectives that inspire effective problem-solving techniques, which in turn guide us to face the sustainability challenges of our times.

Her effectiveness may be due to several factors:

- One major factor is that the ancient storytelling traditions throughout the Americas were mainly smaller social groups, few civilizations consolidated to develop into empires.

- Another reason may be that most of these stories come from social groups and cultures that subsisted with nature.

- And lastly, they relied on the cycles of seasons.

Key Points

-

Early origin and creation mythological stories have distinct ideologies yet share literary tropes

-

Ideologies by Indigenous communities contrast Western versions & inform ecocritical readings

-

Taíno mythology contributes to world literature and informs on sustainability

-

Twin Heroes in origin stories as symbols restore order to complete cycles of seasons

Media Attributions

- Raven’s canoe © Canadian Museum of History is licensed under a CC BY-NC-SA (Attribution NonCommercial ShareAlike) license

- Flying Woman © Canadian Museum of History is licensed under a CC BY-NC-SA (Attribution NonCommercial ShareAlike) license

- Transformation Mask © Canadian Museum of History is licensed under a CC BY-NC-SA (Attribution NonCommercial ShareAlike) license

- Map of the Land of Indigenous communities © Wikipedia is licensed under a CC0 (Creative Commons Zero) license

- Native American NY © Wikipedia is licensed under a CC0 (Creative Commons Zero) license

- Cherokee Phoenix © Wikipedia is licensed under a Public Domain license

- Family tree comparison © PALEOAERIE is licensed under a CC BY-NC-SA (Attribution NonCommercial ShareAlike) license

- Ladder of ascent and decent © Wikipedia is licensed under a CC0 (Creative Commons Zero) license

Indigenous communities is a proper noun that refers to the peoples who have lived throughout North America for over 10,000 years, where they historically call Turtle Island. This territory reaches beyond the borders of today’s Canada and the United States. Hence, Indigenous communities are the “descendants of those who survived the colonizing apocalypse that started in 1492 and continues today” (Justice 2018). They affirm their “the spiritual, political, territorial, linguistic, and cultural distinctions” throughout numerous and varied tribes. Indigenous communities experience stories and their ancestral lands as crucial to the survival of their culture and heritages. They learn and share the world by storytelling, including oral traditions on science, medicinal biological knowledge, and religious rituals. The capitalization of the word Indigenous “affirms a distinctive political status of peoplehood” with agency (Justice 6).

The Mayan culture and their current descendants are the only culture known that developed writing independently. Their books operated like folding storyboards of symbols and figures, known as hieroglyphs, a pictorial symbolic writing system also known throughout ancient Egypt and India.

This proper noun refers to the confederation of Indigenous communities of the Mohawk, Oneida, Onondaga, Cayuga, Seneca, and Tuscarora. This work means “the people of the longhouse” in Anishinaabe, a cultural-linguistic group of tribes, including the Ojibwe, which means “people who emerged from the void.” For more information, visit OER Pressbooks.

Whether people may recognize that the environment includes all aspects of nature – from the cosmos to the Earth’s oceans, atmosphere, and forests with all of its life-forms, from an etymological perspective, the environment has been understood from a human-centric stance. This stance is a mode of anthropocentrism. This means that the environment is inherently viewed through a human-centric lens in many traditions, especially throughout the Western tradition. “Within ecocritical discourse, it is often acknowledged that the anthropocentric views that have developed over the centuries are at the roots of the ecological crisis. To call the nonhuman bodies the “environment,” points to the human body as the center of that environment, which can in itself be considered as an anthropocentric way of envisioning the world...This period is now identified as the beginning of the Anthropocene” (Boom 10). Hence, current climate challenges and ecological crises must be understood from a more ‘neutral’ and informed stance.

Oral tradition involves performing somatic and linguistic cultural codes as a dynamic visual art. These performances involve dancers dressed in sacred clothing with symbolic significances, along with music and dynamic jestering. A social group’s oral tradition is maintained and related through memory and referential communication to make meaning. Social groups communicate their people’s legacies of known institutions for the present generations to learn from and preserve. Oral tradition as performance addresses known understandings of astronomical, cosmic phenomena, biology of fauna and flora, especially about their medicinal and nutritional properties, refer to geographic locations and seasonal phenomena, relate political history and treaties, reflect on philosophical and religious storytelling traditions, and perform rituals on current technologies. Scholars like John Miles Foley point out that once an orally delivered text is written down, its original version has been “reduced,” of a once-living experience to one of bureaucracy, forever eliminating much of its meaning. Oral traditions dwarf written literature in both size and diversity (Foley Native American Oral Traditions).

Postcolonialism precedes global studies and arose after the First World War. Cultures became independent from colonized imperial forces throughout the African continent, India, the Caribbean and South Pacific, and other regions. Intellectuals theorized colonialism and liberation. Visit Key Terms for more details.

Common contemporary usage of the word “myth” means something which is a popular claim, but is not true. In Literary Studies, mythology – like origin stories – refers to epics from oral traditions; a few examples include Sumerian Epic of Gilgamesh, The Iliad, and the Mayan Popol Vuh. Mythology originates from shorter stories, as in fable-like stories and legends and folktales, that were later compiled to create a cohesive narrative. Ancient mythology is intricately part of a social group’s religious cult. Part of folklore, mythology is a storytelling tradition tied to religious doctrine. All of the world’s mythology was polytheistic, as witnessed in Greece, Roman, and Norse mythology, and may have changed, like the Torah, in Christian bibles, and the Quran. Mythology is sustained by its culture and their community’s oral and practicing rituals and religious tradition. Stories on creation, key creators as gods, and supernatural beings are represented throughout world mythology. At times, humans and deities coexist, which is also a major trope in mythology. For more information, visit OER Pressbooks on World Mythology.

According to ecocritic Lawrence Buell’s definition of ecocriticism, which involves the philosophical view that “human being and human consciousness are thought to be grounded in intimate interdependence with the nonhuman living world,” this “interdependence” is the web of life (Buell 2011). According to Danel Wildcat and Dine Deloria Jr. – whose son is currently History faculty at Harvard Dr. Philip Deloria (wiki on Philip Deloria), the worldview, the metaphysics of Indigenous peoples in North America experience reality as ‘related,’ the world is unified, and all aspects have significance and share a commonality among the tangible, spiritual, intelligent, and intangible. “The teachings of the tribe are almost always more complete, but they are oriented toward a far greater understanding of reality than is scientific knowledge”(OER Pressbooks on Indigenous Education, go to Ch. 9). As a more thorough and intuitive philosophy, they expose the limitations and exclusionary culture of Western culture and its reliance on Cartesian dualistic philosophy: “We live in an industrial, technological world in which a knowledge of science is often the key to employment, and in many cases is essential to understanding how the larger society views and uses the natural world, including, unfortunately, people and animals.”

In the most general sense, identity is the sense of oneself, the known self. But in literary studies, identity is quite complex since this word represents a conglomerate of many lived experiences with communities that share social norms and ideologies that contribute to the totality of selfhood, one’s own identity. For more information, visit OER Pressbooks on Identity and Literature.

The concept of nature is a social construct with qualifiers that make nature idyllic, or ‘balanced.’ Yet, in non-Western literary traditions, references to nature reflect real lived experiences, immersed in nature. For example, in Indigenous oral traditions, nature is dynamic. Adamson explains, “They tell of wars, crisis, and famine…they learned to live with ambiguities, to see the patterns, and to mimic natural processes in the cultivation of their gardens” (Adamson 56). Ecocritics and environmental humanists, among other scholars, witness humans as also a social construct in opposition to nature, or the nonhuman, which is witnessed throughout literature. Instances of the feminization of nature are understood as gendered ethnocentric views of nature by those who define humanity as superior to nature, and the masculine gender as superior to the female gender. These social constructions suggest anxieties about what it means to be human and overlap with discourses on power and colonialism when the colonized are effeminate, along with the conquered landscape. The gendering of a people and nature acts as a mechanism that initiated modernity, inequalities ecofeminist Soper addresses, “given the widely perceived parallels between the oppression of women and the destruction of nature” (Soper 1995). Feminist philosopher Kate Soper also argues on how nature is an ‘otherness’ in What is Nature: Culture, Politics, and the Non-Human (1995) to focus on Western attitudes from two schools of thought, on ecology and cultural criticism - that of our current climate crisis and efforts to address this crisis while understanding “the politics of the idea of nature,” on the semiotics of ‘nature’. Intersections between perception of nature and theories of sexuality offer insights into ‘the politics of the idea of nature.’

Representations of the cosmos, animal characters, fantastic deities, and objects like robots in both Western and Eastern texts with human-like characteristics are instances of anthropomorphism (OER on Robots as 'human-like'). Anthropomorphism is also witnessed in religious texts to present divine-like qualities to humans, as the demigods in Greek mythology, Egyptian, and India’s mythology. Its opposite is known as theomorphism, when humans have god-like characteristics like in scripture: “Anthropomorphism ascribes human and nature to the divine”(A WordPress glossary). Yet, Native American literature does not fit this general construction of nature. Their stories allow the animal kingdom to simply be while humans coexist nearby.

A literary trope is a recognizable plot element, theme, or visual cue that has figurative meaning. It can appear within the body of an author’s work, within a tradition, and across cultures as witnessed in world literature and world mythology. A common literary trope is the hero’s journey, which is a plot structure found in stories all around the world. Many literary tropes may not be universally understood, but occur commonly within a specific tradition – like in gothic and fantasy literature, and also in popular comics. Another recognizable literary trope that is observed in Western letters is the symbolism of skulls, like the skull Shakespeare’s Hamlet holds when he delivers his “Alas poor Yorick” soliloquy. In this scene, the skull represents a contemplation of one’s morality in the face of contradicting desires. Yet, as a religious Catholic trope a skull is associated with Jesus of Nazareth, for example. This association may signify more directly with death. Yet, in most religious contexts, skulls are associated with the life-cycle. For example, a skull in Mexican cultural traditions represents this meaning, through rituals associated with the Day of the Dead. They involve visiting and speaking with the deceased at nearby cemeteries, among other rituals; here, the skull signifies the life-cycle. The skull may also share associations with the serpent, like in Chinese and Mesoamerican traditions. Yet, the ‘serpent’ in most Western texts –the New Testament, Ovid’s Medusa, and even popular texts like Harry Potter – is usually associated with demons and the unholy, a finite view of the life-cycle. Another literary trope common in European literary texts is the color ‘white’. In many instances this color means death when associated with snow. Witnessed in James Joyce’s 1914 story “The Dead” from Dubliners, snow is a metaphor that signifies the death of a beloved and of a marriage (Wiki on Joyce's "The Dead" from Dubliners).

The hero’s journey is thoroughly examined in The Hero with a Thousand Faces (1949) by Joseph Campbell. Campbell examines the literary trope of the epic hero throughout world mythology. Visit Key Terms for more details.

In world mythology, an account of the beginning of the universe, solar system, and earth in both Easter, Western, and oral traditions throughout the Americas, including by the Maya in the Popol Vuh, is known as cosmogony.

A symbol is an object, expression or event that represents an idea beyond itself. The weather and light/darkness will often have a symbolic meaning. Survey of Native American Literature: Symbols in Literature

An epic originates from oral tradition, in contrast to the literary epic, and many are written in poetry. With an overarching narrative of several tales woven together, the topics and themes of an epic range from the origins of the cosmos, emergence of life and humanity, and heroes’ journey toward order. Epics were originally sung and performed annually, or a chosen part at a specific season. They relate narratives about people’s geographic sense of home via its plot and characters. Epics may also relate the founding of civilizations and empires. We have many of these epics today because they were eventually written down, like India’s Ramayana and the Mahabharata written in Sanskrit, Spain’s first written epic is El Cid (1100 AC) written in old Spanish, England’s is Beowulf (1000 AC) written in Old English, and France’s is Song of Roland (1000 AD) written in old French, while the Maya Popol Vuh comes in written hieroglyph storyboards and the epic of Sundiata is still orally performed every year in North Africa. Well-known epics include those by Native Americans — the Haudenosaunee Confederation, the Cherokee, the Sumerian’s The Epic of Gilgamesh, Greek’s The Iliad, English Beowulf, N. Africa Sundiata, and the Mayans Popol Vuh. The Creation by the Haudenosaunee (People Who Build A House), a confederation of Indigenous communities included the Mohawk, Oneida, Onondaga, Cayuga, and Seneca, whose territory covered a vast region from the eastern part of North American (what today is known as eastern New England seaboard) to Ohio and northward at Canada’s Lake Ontario.

The plot is the structure and order of actions and conflict in a narrative text or a play: “Freytag suggests a pyramidal model. We pass through exposition, initial incident, growth of action to its crisis, crisis or a turning point, the resolution and catastrophe. The exposition should be brief and clear. With the initial incident we enter upon the real business of the play. The play of motive should be distinctly shown. Proper relation between character and action maintained” (OER On Elizabethan Theater). The plot mythos according to Aristotle - in a play or story is presented by events and the actions of its principle characters, which also achieve artistic and emotional effects.

In Shakespeare’s drama, “Characterization is the fundamental and lasting element in the greatness of any dramatic work.” Characterization is the exhibition of passions, motives, feelings in their growth, engagements and conflicts. Dialogue becomes an essential adjunct to action. The principal function of dialogue is characterization.” Also, “Soliloquy and asides are dramatist's means of taking us down into the hidden recesses of a person's nature, and of revealing those springs of conduct which ordinary dialogue provides him with no adequate opportunity to disclose.”

United Nations Sustainable Development Guide (UNSDG)

In 2015 countries around the world came together to address challenges and needs “For a Sustainable Future” with peace, prosperity, health, equality, and justice for our community members and nature.

GOAL 3: Good Health and Well-being

GOAL 6: Clean Water and Sanitation

GOAL 7: Affordable and Clean Energy

GOAL 8: Decent Work and Economic Growth

GOAL 9: Industry, Innovation and Infrastructure

GOAL 11: Sustainable Cities and Communities

GOAL 12: Responsible Consumption and Production

GOAL 16: Peace and Justice Strong Institutions

GOAL 17: Partnerships to achieve the Goal

“A more or less systematic ordering of ideas with associated doctrines, attitudes, beliefs, and symbols that together form a more or less coherent philosophy or Weltanschauung for a person, group, or sociopolitical movement” (APA Dictionary qtd. BU Equity Guide). In schools of thought such as political science and psychology, ideology is addressed as a system of beliefs that underpins and sustains the form of a society. A school may be supported by an ideology of curricular vigor that rewards certain achievers. The economy of a country may be supported by a capitalist ideology. But, ideology is also understood through other worldviews and cultural norms, like those practiced by the Indigenous communities of the Americas.

A concept that encompasses the dynamic and intricate network of how humanity affects communities, the environment, and climate. Current efforts to address a wide array of cultural and sociological practices that are all interrelated and connected to seriously address the causes and effects of ‘climate instability’ and other injustices that plague some societies while threatening the rest. The United Nations offers 17 goals of development to highlight many facets of society – from the production of goods and treatment of women and the impoverished and social justice and renewable energies (UNSDG ). Yet, current scholarship by ecocritics in literature emphasizes the fundamental need to address today’s crisis – a sustainable ideology, to demystify human and nonhuman binary thinking. Where we as a global people realize that we are interconnected to local and global ecologies. This worldview can also demystify current human tendencies of placing humanity above the nonhuman. An example of this argument is witnessed in Frank Boom’s ecocritical analysis of Ovid’s Metamorphosis, Book 10 and 11, on the mythological tales of “Orpheus and Cyparissus” (OER Article on Today's Climate Crisis & Ovid's "Metamorphoses").

Joni Adamson is known for her literary scholarship on ecocriticism and the literature of Indigenous communities, demonstrated in American Indian Literature, Environmental Justice, and Ecocriticism (2001). Visit Key Terms for more details.

Claiming to be greatly influenced by Greek and Roman traditions, the Western literary tradition also reflects Arabic scholarship that includes the East – along with its technologies and cultural exchanges – and Indo-European linguistic traditions throughout Europe and its colonized territories – like the Americas – known as the romantic languages. This excludes Indigenous peoples and Slavic; yet, semitic language, religious thought, and near East influences are part of the Western tradition.

A formal academic discipline, Literary Studies seeks to understand literature in its totality through its disciplinary subsets like literary history, literary criticism, literary theory, schools of thought, and multidisciplinary scholarship like Gender Studies, Cultural Studies, and Film Studies. As an academic discipline, engagements in Literary Studies always look into language usage in literary history and literary traditions. “Literary Studies is concerned with the ways that language is used. If it isn’t concerned with language use, it isn’t Literary Studies. Literary Studies is about the ways in which writers use the formal resources of literature to represent and comment upon life” (Aphorisms on Literary Studies). A Literary Studies course with an ecocritical interpretative approach aims to learn from different disciplines and various literary traditions. Its purpose is to expand traditional literary inquiries in order to articulate more concrete understandings of the human-nature binary, environmental challenges, and social justice. These intersections allow learners to identify representations of nature to investigate cultural norms practiced and become informed on the role of ideology in storytelling traditions. Storytelling traditions include various branches of Literary Studies, including on the literary traditions of Indigenous communities, American Studies, Black Studies, Comparative Literature, English Studies, Ethnic Studies, and World literature. The combination of literary traditions in literary studies enhances learning experiences that both inform and challenge learners and educators alike to address themes associated with sustainability, like those proposed in the United Nations’ Sustainable Guide (UN's Guidelines). “The end of literary studies is a discussion of how literary writers use formal rhetorical devices to represent life, thereby giving us new ways to understand and experience our world…the end of literary studies is not, for example, the recognition that Milton used blank verse in Paradise Lost. The end of literary studies is a discussion of how Milton used blank verse in Paradise Lost to associate the Christian empire he represented with the English nation” (Aphorisms on Literary Studies). This approach to literary studies aims to enhance collaborative engagement by its coursework, lesson plans, and group projects that contribute to our viable futures.

Literary theory involves philosophy and schools of thought to understand literature. As a systematic account of the nature of literature, literary theory offers approaches to literature from a particular set of principles. These principles involve a “body of ideas and methods we use in the practice of reading literature. Not the meaning, but the theories that reveal what literature can mean'' (Literary Theory | Internet Encyclopedia of Philosophy). It is literary theory that gives us approaches on how authors and their texts relate – on the significance of class, gender, race, etc. – and from standpoints that include biographical information on an author and the text or on the linguistic and unintended aspects of a text. Hence, literary theory provides the ‘tools’ necessary to understand literature in depth. Literary theorists can trace the histories of texts to understand genre formations and to view literature as a collective, rather than as an individual cultural artifact. For example, Joni Adamson provides literary theory, cultural studies, and ethnic studies to offer ecocritical scholarship on Indigenous literature to address their sustainable storytelling traditions. Literary critics apply literary theory to a text or to a literary tradition. Literary critics rely on literary theory to understand literature. This relationship may cause some confusion between literary criticism and literary theory. Just remember that the purpose of literary theory is not to determine a causal sequence, but to engage in analyzing the corpus of an individual author or poet through a theory, like ecocriticism, feminism, or Marxism.

Intersectionality is the “study of overlapping, intersecting social identities and related systems of oppression, domination, or discrimination” (Syracuse University). Intersectionality was first posed on Langston Hughes poetry to highlight intersections between racism and the legacy of slavery with environmental exploitation and that of Black laborers, where learners can conduct further research on such overlapping topics. For example, learners can research Black oppression in the 1840s through the work of America’s first ‘Father of Black Nationalism’ Martin R. Delany, in order to learn about the effects of slavery, while researching Joni Adamson’s work on environmental devastation. Intersectionality is a concept coined by American law expert Dr. Kimberlé Crenshaw in a 1989 paper to address the oppression of African women to address that gender and racism are not “mutually exclusive categories of experience and analysis.” In legal matters, injustices on both gender and race are considered separately in the U.S. The tendency to simplify a composite of injustices that are all related is described as interpreting the law on a ‘single axis framework’ (on its history). To remedy this oversimplification, Crenshaw coins the idea of ‘intersectionality’ as an approach that recognizes the complex composite nature of an injustice that reflects several injustices at once. Her goal is to make Black women more visible and for the law to acknowledge their plight as women of color (Sociology & Intersectionality). Intersectionality is a lens through which you can see where power comes and collides, and where it interlocks. “It’s not simply that there’s a race problem here, a gender problem here, and a class or LBGTQ problem there. Many times that framework erases what happens to people who are subject to all of these things'' (Columbia Law School).

The EPA (Environmental Protection Agency) defines environmental justice as “the fair treatment and meaningful involvement of all people regardless of race, color, national origin, or income, with respect to the development, implementation, and enforcement of environmental laws, regulations, and policies (wiki). The 17 Principles of Environmental Justice in 1991 reflects the work and experiences of those who live in communities where toxic waste has decimated their ecosystem. For more information, visit OER Pressbooks on Environmental Justice.