Citing Your Sources

When I ask students why we cite sources, they usually tell me two things: so that we don’t get accused of plagiarism and so that we give credit to other people for their work. While the former is true, the latter is much more important.

When I ask students why we cite sources, they usually tell me two things: so that we don’t get accused of plagiarism and so that we give credit to other people for their work. While the former is true, the latter is much more important.

People who are honest about their intellectual work want to get credit for that work, and they want to give credit to those who have helped shape their ideas. If you write something that makes a difference and is worth quoting, wouldn’t you want to get credit?

In addition, we cite so that others can find our sources. Frequently, as I am reading someone else’s research, I see a source that I want to understand better. The citations help me locate that source for my own use.

The desire to give credit means that we need to acknowledge our sources. The desire to help others locate our sources means that we need to follow style guides. Those guides provide conventions for citing, and if we follow those guides, readers familiar with those conventions should have no trouble locating the sources.

Citation is one of the few places in academic writing where the ideas “right” and “wrong” apply. There are rules, and you should follow them to the best of your ability.

In this section, I’m not going to provide a guide for using any specific style. You can find those guides in lots of places, including on the internet. Instead, I’m going to explain how citation works so that you can apply these principles to your projects.

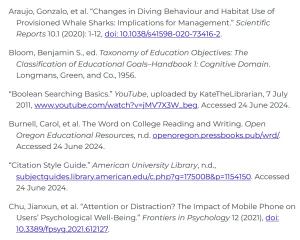

Understanding Citation Styles

There are many citation styles, usually specific to different disciplines. For example, disciplines like psychology and education use the American Psychological Association (APA) style, while literature uses the Modern Language Association (MLA) style and biology uses the Council of Science Editors (CSE) style. Some disciplines use more than one. Business, for example, might use APA, the Chicago Manual of Style (usually just called “Chicago”), or Harvard Business School style (usually just called “Harvard”). You can find a number of guides for choosing styles online, like this one from the American University Library.

There are many citation styles, usually specific to different disciplines. For example, disciplines like psychology and education use the American Psychological Association (APA) style, while literature uses the Modern Language Association (MLA) style and biology uses the Council of Science Editors (CSE) style. Some disciplines use more than one. Business, for example, might use APA, the Chicago Manual of Style (usually just called “Chicago”), or Harvard Business School style (usually just called “Harvard”). You can find a number of guides for choosing styles online, like this one from the American University Library.

You won’t need to learn all of these, even when you are taking classes in those fields. You should plan to learn the primary style (or styles) for your discipline, but for specific classes, your professor can tell you which style you should use. And many professors of general education courses will just tell you that you need to follow a style guide, but they are indifferent about which one.

There are so many different styles in part because different disciplines have need for different information about sources. For example, many styles include the year of publication of the source in the in-text citation, but MLA doesn’t. That’s because for the disciplines that use MLA, the date of the research is not terribly important. As another example, many sources in the sciences use a note numbering system and highly abbreviated reference list entries because publishing in the sciences can be expensive, and no one wants this kind of information to take up much space.

Starting with Reference Lists

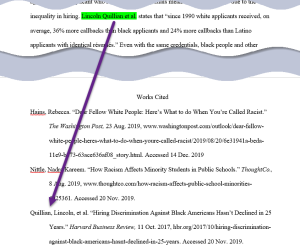

Most citation styles require two parts: (1) the list of references at the end of your text and (2) the in-text citations. These two parts must work together in order for citations to do the work they need to.

The list of references goes by a few different titles. MLA uses “Works Cited” (or “Work Cited” when there is only one source). Styles like APA use “References.” Some, like Chicago, use either “References” or “Bibliography,” depending on whether you are using the note version of the style or not. You can find specific information about the style you are using online at sites like the Excelsior OWL or through your university library website. You can also often buy guides for specific styles designed for students, but I wouldn’t bother purchasing these unless you know that you will need them for your major.

Until you are familiar with how a style works, you should plan to do your list of references first because the in-text citations for those styles depend on your reference list entries. Many styles, including MLA and APA (two very common styles in college-level work), rely on the author’s names or an abbreviated version of the first words of the reference list entry. If you don’t know what begins an entry, you’ll have trouble writing an accurate in-text citation. Once you become comfortable using that citation style, you may be able to draft your in-text citations without the reference list entries.

For styles that rely on numbering, like the American Medical Association (AMA) style or some versions of the Council of Science Editors (CSE) style, your citations appear in the list in the order that they appear in your paper. In these cases, it may be better to order your reference list as you draft and revise—and work on finalizing your list later.

Your complete list of references includes all of the bibliographic information necessary to allow your reader to find your source. The style guide you are following tells you what information to include and how to arrange it.

To help your reader locate the proper source in your list, style guides that use a references list following one of two organizational strategies:

- Alphabetical order by whatever is first in the entry. While this is usually an author’s name, sometimes you may be using sources written by institutions or other organizations and you don’t have a person’s name. For the purposes of alphabetization, you treat the first words in the entry just like an author’s name. This is the most common strategy, and the one you are almost certainly going to be asked to use in the course where you are using this textbook.

- Numerical order according to the order in which the sources appear in your project. This ordering appears mostly in scholarly articles in the natural sciences, but you may see it in other places.

The organizational method you use will be dictated by the style guide that your professor requires. And you should follow it, even if you only have two or three sources.

Creating In-Text Citations

The other half of a complete citation is the in-text citation. There are three kinds of in-text citations:

The other half of a complete citation is the in-text citation. There are three kinds of in-text citations:

- The first, often called parenthetical citation, provides information inside of parentheses that indicates the corresponding source from your reference list. This is the most common form in both the humanities and the social sciences.

- The second kind is a superscript number. This is only used in styles that use a numbering system, and just like a parenthetical citation, the number indicates a corresponding reference. You will see this more frequently in the natural sciences.

- The final kind is a reference in the sentence itself, usually as part of an introductory phrase or other attributive tag. Like the other kinds of in-text citation, you must include enough information that your reader can locate the source in your list of references. This kind is sometimes used in conjunction with the first two kinds. It is most common in the humanities and relatively rare in the natural sciences.

You will use parenthetical in-text citation in most of your early college coursework, so I am focusing on it here. Keep in mind that you should check on the rules if you are being asked to use an unfamiliar style.

Both quotations and paraphrases require in-text citation, though the specifics vary depending on the style guide you are using:

- Most styles want the author’s name or names when there is more than one, though they have some differences about how to refer to multiple authors. You will sometimes see “et al.” following an author’s last name. This indicates that there is more than one author, and almost always it means that there are more than two.

- Many styles ask you to include the year of the source in the parentheses. This is so that readers can know immediately how current the source is.

- Most style guides require page numbers for every quotation, even a partial quotation.

- Some style guides, such as MLA, require page numbers for paraphrases as well as quotations. Even when a style doesn’t require page numbers for paraphrases (e.g., APA), your professor may want them anyway. Be sure to check.

For details about what should go in the parenthetical citations, head for a reference like the Excelsior OWL’s Citation and Documentation section. And be sure to check with your instructor and/or a writing tutor if you have any questions.

The Jobs of In-Text Citation

All three kinds of in-text citation have three primary jobs in your text:

All three kinds of in-text citation have three primary jobs in your text:

The first job is technical: It must lead your reader to the correct complete citation that appears in your list of references. This is why, for example, a parenthetical citation must start with the same information as the full reference list entry. If your reference list entry starts with an author’s name, your in-text citation for that source must start with the same name so that your reader can find it in your alphabetical list of entries.

The second job of an in-text citation is to acknowledge your sources at the moment you are using them. Knowledgeable readers—which probably include your professors—may recognize the source you have chosen just from the citation. But even if a reader doesn’t recognize the source, your citations make clear that what you have just presented is someone else’s idea and may give a little information (such as the year) to contextualize that source.

The final job of an in-text citation is to clarify which ideas are yours and which belong to someone else. This is why you must be careful with your placement of citations. If you have a sentence begins with a paraphrase from a source followed by your own idea, you cannot put the citation at the end of the sentence. That placement would indicate that your idea is actually an idea from the source. This need for clarification is why most sentences only contain ideas from sources or ideas from the writer, but not both. Citation placement is much simpler and, more importantly, the meaning is clearer when a sentence only contains one or the other.

Checking Citations

Arguably, checking citations could be considered part of proofreading as much as editing because citations are highly technical. However, I decided to put this section in this part of Reading and Writing Successfully in College instead of in the process section because it is too easy to make mistakes in citation. Those mistakes can get in the way of a successful project—and even end up in accusations of plagiarism. Here, I focus on some trouble areas and some tricks for checking citations.

Checking the List of References

Start with the entries themselves. Pay attention to things like the following:

Start with the entries themselves. Pay attention to things like the following:

- How authors’ names are spelled

- Where italics are used—and where they aren’t

- Where periods and commas go—and where they don’t

- Whether you have included all of the required information, including things like publication dates and accessed dates (where required)

If at all possible, you want to look at a sample list of references for that style (or from your professor) and make that your list looks as much as possible like that one. Here are some specific areas to check in the formatting:

- Have you given your list a heading (e.g., “Works Cited” or “References”)?

- Have you used a hanging indent? If you don’t know how to do this, Bibliography.com has pretty clear instructions for both Word and Google Docs (Mathewson).

- Are the sources in alphabetical order by the first word in the entry?

- Is this list double-spaced without extra spaces between the entries?

- Does this list start on a new page if that is what your style requires?

- Does the list appear in the same fonts and type size as the rest of your paper? Sometimes, if you copy and paste all or part of an entry, you’ll end up with different fonts.

Checking Your In-Text Citations

Keeping in mind that your in-text citations must match your reference list entries, you will want to check every in-text citation to make sure that it’s accurate. Do the following to check your in-text citations:

Keeping in mind that your in-text citations must match your reference list entries, you will want to check every in-text citation to make sure that it’s accurate. Do the following to check your in-text citations:

- Use the search feature to find all of your in-text citations. Highlight the citations as you find them so that you can more easily see them as you work.

- Search for “(“ to find all of them that appear in parentheses.

- Search for the names of authors to locate any that appear only in introductory phrases or attributive tags.

- Search for quotation marks to find any quotations (all of which should have a citation).

- Scan your text to find anything you missed. Look, in particular, for the following:

- References to authors that don’t appear in your list of references

- Paraphrases that you did not cite

As you go, make corrections if you find mistakes.

Once you have located and highlighted all of your in-text citations, you can look for these specific problem areas:

- Every source that appears in your list of references must also have some kind of in-text citation. If the source is not cited in your text, it doesn’t belong on your list.

- Every in-text citation must match an entry on your list of references.

- Be sure to check the spelling of authors’ names so that you are accurate each and every time.

- Be sure that whatever is in your in-text citation also starts your reference list entry.

- Check your sources, especially the page numbers. It is worth taking a little time to be sure that you can locate the point in the original source that you are referencing.

While this may seem tedious, as you become more adept at working with citations at the college level, you will find yourself better able to do this work efficiently. You’ll also know better where your trouble spots are, and you can focus your efforts there.

Key Points

- We use to citation to give credit to our sources and to help our readers locate those sources if they are interested. Citation is necessary to avoid accusations of plagiarism, but that’s not a primary reason for citation.

- There are many citation styles The ones you will need to use are dictated by your professor and your discipline.

- Citation consists of two parts: a reference list and in-text citations.

- The reference list entries will include all bibliographic information (per the style guide) and will usually be arranged alphabetically by the first word in the citation (usually an author’s last name).

- The in-text citations usually appear in parentheses and those citations must match the first word in the reference list entry so that a reader can find the source in the references list.

- In-text citations also clarify which ideas are yours and which belong to your sources, at the same time as they give credit to those sources.

- Be sure to check that your citations are correct and that you have a complete match between in-text citations and reference list entries.

Media Attributions

“Checklist-icon” by Clker-Free-Vector-Images on pixabay, Wikimedia Commons is in the Public Domain, CC0

“Checklist” by pixabay, Wikimedia Commons is in the Public Domain, CC0

A usual or customary way of doing something. In writing, the term is most commonly applied to grammar and citation.

A phrase embedded in a sentence that indicates the source of the information in that sentence. Sometimes these tags can serve as citations, particularly when there are no page numbers to reference.

An abbreviation used to indicate additional authors. Formally, it is an abbreviation for "et alia," which is Latin for "and others."

An area of study, very similar to a major in college.