Revising 2: Revising Paragraphs

While making global revisions, you have probably also worked on revising paragraphs to clarify your point or add more explanation. That work is important, but the strategies in this section are designed to help you make sure that your individual paragraphs are solid by looking at the specific qualities of good paragraphs: focus, development, and coherence. These can be particularly useful for paragraphs that don’t seem to be working well.

Color Coding Topics: A Strategy to Strengthen Focus

A focused paragraph has one main idea that usually appears in a topic sentence (at least in academic writing), and the rest of the paragraph elaborates on that idea. If your paragraph isn’t focused, your reader may struggle to follow your point and the connections among the ideas in your paragraph.

This activity works on body paragraphs, but not really on introductions or conclusions. As with previous activities, you can do this with the highlighter feature in your word processor or with actual highlighters on a printed copy of your paper.

Part 1: Highlighting

View the instructions.

- Identify the paragraph’s topic sentence and highlight it in one color.

- Look at the next sentence (or the first sentence in the paragraph if the topic sentence isn’t the first sentence), and decide if it’s on the same topic. If it is, highlight it in the same color. If it isn’t, highlight it in a different color.

- Continue highlighting this way, matching the highlight color to the sentence topic, until all of the sentences in the paragraph are marked. Note that you can have split sentences (sentences that have more than one topic in them). In those cases, highlight the parts of the sentence in different colors accordingly.

Part 2: Analyzing Your Highlighting

View the instructions.

- If your paragraph is all one color, then you have a well-focused paragraph.

- If your paragraph contains two colors, it’s probably fine. Paragraphs can shift focus sometimes, so a paragraph that has two colors may still work as a single paragraph. Look carefully at the topics to make sure that they are connected and that you haven’t dropped in a new topic in that really belongs in a different paragraph.

- If your paragraph has three or more colors, you probably need to think about separating the topics.

- I frequently see this problem when the writer starts a paragraph on one idea, realizes that they need to explain a specific point before getting into the original topic, and then shifts back to the first topic, with an additional shift in topic later in the paragraph. Often, that second topic can be pulled out and developed into a new paragraph that is placed before the current one.

- This can also happen when the paragraph is very long and simply isn’t broken into chunks to make reading easier. Look for those moments when the colors shift, which can indicate good places for paragraph breaks. The new paragraphs might also need a little development (see the next strategy).

Examples: Color-Coded Paragraphs

View the examples.

Here are some examples of paragraphs with one, two, and three colors.

Example 1

If you look up at the sky, you’ll notice it’s blue during the day. The reason why the sky is the color we see is because of how the light bounces, causing us to see a light blue instead of red. The light blue we see is also very beautiful, and an activity that some people enjoy doing is looking up at the sky.

While the paragraph above is relatively short, every sentence ties in with one another. Of course, the paragraph could use more work, but the paragraph is well focused.

Example 2

If you look up at the sky, you’ll notice it’s blue during the day. A question that children often ask adults is why this is. However, not many people can come up with an answer, even if they’re taught in school. The reason why the sky is the color we see is because of how the light bounces, causing us to see a light blue instead of red. By the time people become adults, they tend to forget how and why this is, causing them to simply state that they don’t know when children ask. The light blue we see is also very beautiful, and an activity that some people enjoy doing is looking up at the sky.

This is an example of a paragraph that shifts focus but sticks with the main point. While this one probably doesn’t need to be broken up (though it could benefit from some reorganization), you can have a paragraph that has two colors where the different sentences shift focus drastically. Such a paragraph would need to be broken up.

Example 3

If you look up at the sky, you’ll notice it’s blue during the day. A question that children often ask adults is why this is. However, not many people can come up with an answer, even if they’re taught in school. But did you know that in California, the sky has sometimes turned orange due to fires? Residents couldn’t even leave their homes, even if the sky looked hauntingly beautiful. The reason why the sky is the color we see is because of how the light bounces, causing us to see a light blue instead of red. By the time people become adults, they tend to forget how and why this is, causing them to simply state that they don’t know when children ask. The light blue we see is also very beautiful, and an activity that some people enjoy doing is looking up at the sky.

While this paragraph has mostly the same focus points as the previous example, look at the blue section. These two sentences would work better as a topic sentence in a new paragraph due to the focus shifting away from the sky being blue to the sky being orange in California.

Occasionally, multiple colors in the same paragraph indicate a larger problem with topic organization throughout the paper. When this happens, the same topics appear in small clumps throughout the paper. One of my former students called these “rainbow paragraphs.”

As you can see in the example below, there’s a glaring issue with the focus of the paragraph. While the yellow and green sentences could work together, the other three colors would work best as their own paragraphs.

If you look up at the sky, you’ll notice it’s blue during the day. A question that children often ask adults is why this is. However, not many people can come up with an answer, even if they’re taught in school. But did you know that in California, the sky has sometimes turned orange due to fires? Residents couldn’t even leave their homes, even if the sky looked hauntingly beautiful. A great way to learn about major fires is the news. Time and again, forest fires in the United States are shown on the news. People who have done gender reveal parties have recently been responsible for fires. These parties tend to involve fireworks or other explosives, and the people handling them don’t think of taking any precautions.

Rainbow paragraphs are really a global-level revision problem rather than a paragraph-level revision problem, and you can find them by doing a more complete version of this focus activity.

If you suspect you have a rainbow paragraph problem, create a key where you color code different topics in your paper, and then highlight according to that key. You can then gather all of the sentences that deal with each topic to work together in one or more paragraphs.

Revisiting the Evidence/Explanation Balance: A Strategy to Strengthen Development

A paragraph that is sufficiently developed has enough evidence and enough explanation, with “enough” being defined mostly by the reader. You can use the same kind of highlighting activity that you did for your entire paper to make sure that you are balancing evidence and explanation at the paragraph level, too. This strategy can help you identify paragraphs with too little evidence or too little explanation.

In the case of too little evidence, you may find that you thought your reader would already understand your point. To you, the point seems obvious, but keep in mind that your reader has not been working with the evidence that you have. Show them the source material that supports your ideas.

In the case of too little explanation, students commonly try to let the evidence speak for itself. But, as I said earlier, evidence itself is neutral. Evidence exists out in the world and doesn’t mean anything until we start interpreting and explaining it. You need to provide your reader with some of that explanation.

This activity can help when you have a paragraph that you believe is out of balance (something you might have noticed if you did the full project evidence/explanation balance activity).

Part 1: Highlighting

View the instructions.

Using the highlighting feature in your word processor or actual highlighters on print versions, do the following:

- Highlight or otherwise mark all the supporting evidence in the your paragraph.

-

- From textual sources, this would include quotations and paraphrases, facts, examples, and background information. Include the attributive tags and citations in these highlights.

- You can also do this with evidence from personal experience and observations or data that you have personally collected. These would be evidence in projects that don’t rely heavily on published sources.

- Using a different color, highlight or otherwise mark differently all of the explanations of that evidence that you have provided. This material should all be coming from your own ideas.

- Be sure that you have highlighted every sentence in the body of your paragraph. Note: You may have sentences that are part evidence and part explanation. That is perfectly fine.

Part 2: Analyzing Your Balance

View the instructions.

Your focus here is a bit different from the earlier balancing activity where you examined the balance in your entire paper. Here you are looking for large-ish blocks of one color or the other in a single paragraph, usually three or more sentences. Those blocks are potential problem spots.

- Blocks of evidence can indicate the need for more explanation. While sometimes you will spend the majority of a paragraph providing a summary or an extended example from a source, much more often, you will want to present a little evidence (perhaps a sentence or two) and then explain how that evidence relates to your thesis or your point in that paragraph.

- Blocks of explanation can indicate the need for more evidence. Work through your sentences and determine whether a skeptical reader (one who doesn’t automatically agree with you) would be inclined to ask “How do you know?” If you find any of those moments, look for evidence you can bring in to support your point.

Don’t assume that you need to make a change every time you have one of these blocks, particularly when the blocks are explaining one of your points. Sometimes, these larger blocks are necessary.

Mapping Paragraphs: A Strategy to Strengthen Logical Coherence

A coherent paragraph holds together logically and stylistically; the ideas flow from sentence to sentence so that the reader can understand the author’s line of thought. Stylistic coherence is discussed in the editing section, but logical coherence is a paragraph-level matter.

When a paragraph coheres, it holds together topically—like a focused paragraph does—but its sentences logically lead your reader, step-by-step, through your thinking.

The activity below can pick up problems with focus as well as coherence, so if you don’t have substantial difficulties with focus, this activity might be a better choice for you. Also, unlike the focus activity, this one works on all paragraphs, including introductions and conclusions.

This activity can work well when you have a paragraph that feels jumbled or jumpy. It may be all on the same topic (so it may pass the focus test), but it still isn’t connecting well from point to point.

This exercise can be done on a computer, but it is probably easier to draw the map on a piece of paper.

Here, I’ll use an example paragraph:

View the example.

(1) The technology barrier is what humanity will need to work on. (2) Even if we could convince everyone to pay the enormous prices of installation and switch to clean energy, we still would not have the technology to support this substantial change. (3) Nevshehir states that the technology that we have today is still expensive and not powerful enough compared with what fossil fuels deliver. (4) Fossil fuels have one major advantage over renewable resources: Oil-based fuels are stable and predictable. (5) On the other hand, solar and wind electricity production can vary, which can leave people’s homes vulnerable to energy shortages. (6) Moradiya brings another barrier into the technology issue when he states “Although the development of a coal plant requires about $6 per megawatt, it is known that wind and solar power plants also required high investment. In addition to this, storage systems of the generated energy are expensive and represent a challenge in terms of megawatt production.” (7) In these sentences, Moradiya shows that in addition to the costs of installing the power generators (e.g., solar panels and wind turbines), the costs to store excess energy can be a major hurdle, since the technology that we have today makes large batteries that could sustain cities expensive.

Works Cited

Moradiya, Meet A. “The Challenges Renewable Energy Sources Face.” AZoCleantech, 11 Jan. 2019, www.azocleantech.com/article.aspx?ArticleID=836.

Nevshehir, Noel. “These Are the Biggest Hurdles On The Path to Clean Energy.” World Economic Forum, 19 Feb. 2021, www.weforum.org/agenda/2021/02/heres-why-geopolitics-could-hamper-the-energy-transition/.

Part 1: Create the Map

View the instructions.

- Number all the sentences in your paragraph. Notice that sentences in a quotation are considered all part of one sentence (sentence 6 in the example).

- For each sentence after the first one, draw lines to indicate which sentence that one logically follows from. Looking at the topic of each sentence can help.

-

- Use solid lines to indicate a clear logical connection between sentences.

- Use dashed/dotted lines to indicate a connection that isn’t as clear or strong as it could be.

- It is possible that a sentence may connect to more than one sentence.

- Sentences that are disconnected from all of the others in the paragraph should have no lines.

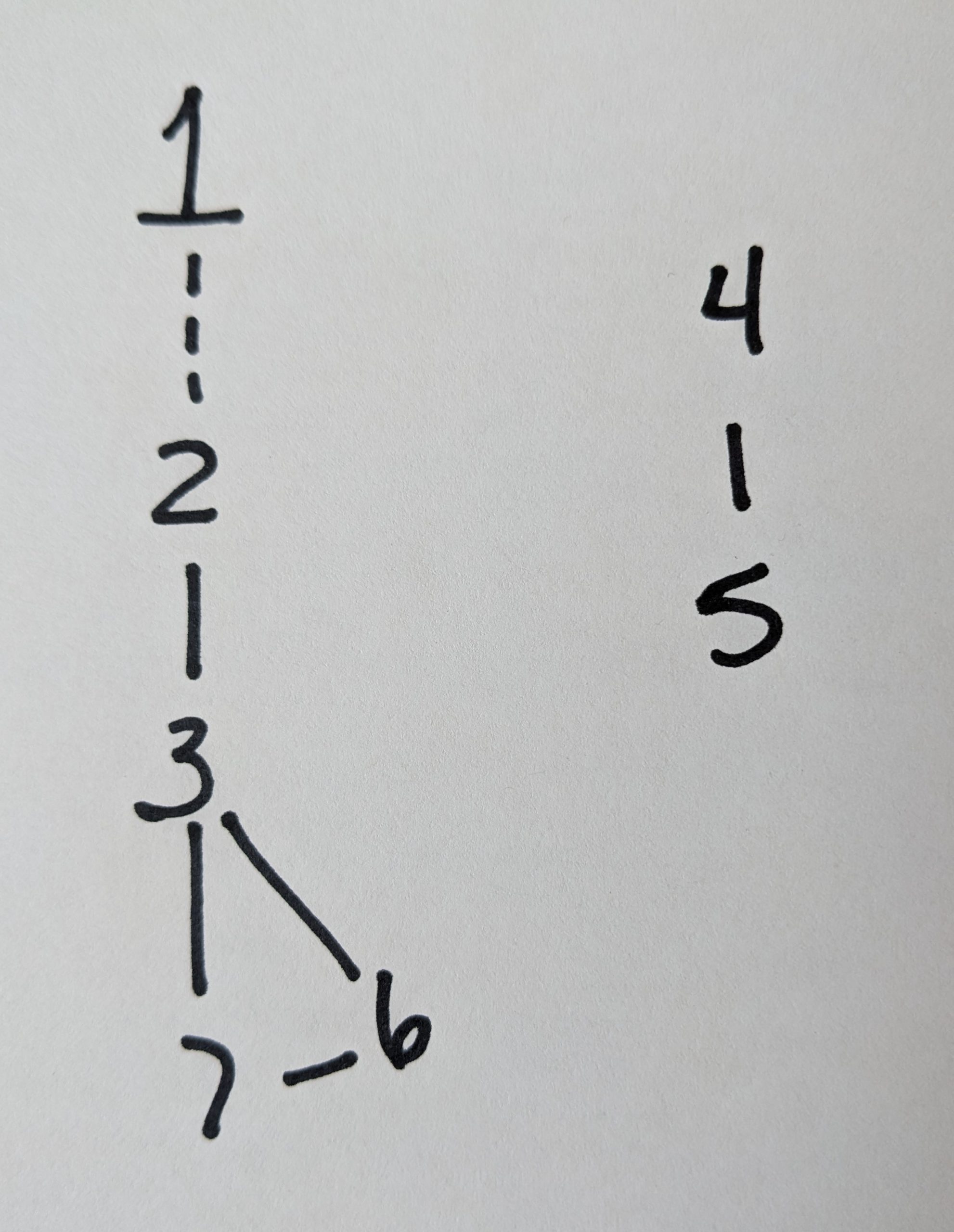

To the right, you’ll see a map of the paragraph above. In this map, sentence 1 is only loosely connected to 2. Sentences 2 and 3 are solidly connected and sentences 6 and 7 are solidly connected to each other and to sentence 3. Sentences 4 and 5, however, are connected to each other, but not to the rest of the map.

Part 2: Analyze the Map

View the instructions.

Once you have created the map, you can use it to identify and correct trouble spots.

- Here are some of the most common problems:

- Sentences that aren’t connected to any others in paragraph (sentences 4 and 5 in the diagram). These usually indicate a sentence or group of sentences that belong in another paragraph. I see this most frequently with transition sentences that appear at the end of a paragraph instead of the beginning of the next. I also see this with ideas that need more explanation, sometimes in a separate paragraph.

- Sentences connected by dashed/dotted lines (sentences 1 and 2 in the diagram). These sentences probably belong together, but the logic between isn’t as clear as it needs to be for the reader to follow. These connections can often be strengthened by adding a little more explanation to one of the two sentences—or sometimes in a sentence between them.

- Sentences whose connection jumps over sentences (sentences 3 and 6 in the diagram, which skip over sentences 4 and 5). Usually, this means that the sentences are out of order. Try moving the sentences so that those that are connected on your map are next to each other. You may have to adjust the wording of the sentences, including transitions, as you do this.

- Not everything in a map is necessarily a problem:

- A single sentence with multiple sentences connected to it (sentence 3 in the diagram). This probably indicates an important sentence for helping your reader understand the relationships among the ideas in your paragraph. Usually, these don’t need any revision—at least not because of this.

- A late sentence that comes back to an early sentence in your paragraph (not seen in this diagram). This is often a way of either wrapping up an explanation and making the connection clear to your reader or starting a new explanation from a key central sentence in the paragraph. Usually, these don’t need any revision.

- Long chains of sentences in the same paragraph (not seen in this diagram). These may be a problem if your paragraph is very long. Look at whether one or more of those chains should be turned into a separate paragraph.

Checking Introductions and Conclusions

Whether we draft our introductions first, last, or somewhere in the middle, we are often at a different place in our thinking when we draft our conclusions. As a result, sometimes the ideas in the two paragraphs don’t align.

Also, sometimes a conclusion sounds more like an introduction. When I ask students to do the mixed-up paragraph exercise, about 20% of the students in any given class end up with the introduction and conclusion switched. This usually happens when the conclusion does too much summary work and not enough gesturing forward.

The following activity can help you identify problems with both paragraphs and check the alignment between the two.

The first part of this activity can be more effective with a partner who knows the assignment but who isn’t familiar with your paper, but you can do this with someone who doesn’t know the assignment, or you can do it for yourself as long as you have given yourself enough time to come back to your paper as a reader.

Part 1: Thesis and Content Work (done by a partner, ideally)

View the instructions.

Use the highlighter feature in your word processor or an actual highlighter on paper to do the following (be sure to set up a key to the color-coding):

- Analyze the introduction:

-

- Highlight the sentence you believe is the thesis statement.

- If there is more than one sentence that you believe could be the thesis or that you think need to be together to make the thesis, make a note of the issue.

- Analyze the conclusion:

-

- Highlight/mark the restated thesis in the same color as you did the thesis in the introduction.

- Highlight/mark (in another color) any other sentences that seem to be summarizing the paper.

- Highlight/mark the gesture forward in a third color, and identify which approach you think the author is using in that gesture. Information about possible gestures appears in the conclusions section.

- Make note of any suggestions you have for strengthening the conclusion.

- Make a list of what you expect to see in the paper based just on the introduction and conclusion:

-

- Add a few spaces between the introduction and the conclusion paragraphs.

- In the space you have created, make a list of the topics you expect the author to cover, based on what you see in the introduction and conclusion.

Part 2: Reviewing the Feedback (done by the author)

View the instructions.

- Look at the highlighting of the thesis in your introduction. If the identified sentence was not what you thought your thesis was, think about whether and how to revise it so that it is clearer.

- Look at the highlighting of the restated thesis. If the identified sentence was not what you thought your restated thesis was, think about whether and how to revise it so that it is clearer.

- Compare the two statements of the thesis. Are they making essentially the same claim? Are they using distinct phrasing? You want both of these answers to be “yes.”

- Look at any additional summary that was highlighted in the conclusion. Try deleting that summary. Remember that the reader of a college-level paper is expecting a gesture forward, not a recap, unless the paper is long (more than about 2000 words).

- Look at the material marked as your gesture forward. Was this material identified in the way you had intended? If not, what could you do to make it clearer?

- Look at the list of topics that your partner thinks would be covered in this paper. Make note of any that differ from your actual organization. Significant differences could signal a need to return to global revision.

Once you have looked at all of these aspects of the feedback you have received, ask your partner about any of his/her feedback that you don’t understand. Then, write up notes on what, if anything, you are going to change and what you are not going to change based on this feedback.

Checking Paragraph-Level Transitions

During your revision process, you may have moved sentences and paragraphs around to make your meaning clearer. At this point, it is a good idea to check your transition sentences to make sure that they are conveying the logic and connections you want to make.

Remember that transition sentences almost always begin paragraphs, and they should make a gesture backward and a gesture forward so that your reader understands the connections between those paragraphs. While there may be a transition between your introduction and your first body paragraph, transition sentences are more important in later paragraphs, where you should be using them to help your reader see how the ideas in different paragraphs connect.

To make sure that your transition sentences are doing the work you want, do the following for each paragraph after the introduction:

- Identify the transition sentence. Remember that this will almost always be the first sentence of the paragraph.

- Check the gesture backward. Does the sentence give your reader some information that they already know from the previous paragraph(s)? It can sometimes help to highlight this part of the transition sentence to make sure that you can identify it. These parts may include the following:

-

- Repeated words, phrases, or even clauses from the previous paragraph

- Transition words

- Summaries of ideas previously discussed

- A reminder of the thesis of the project or the main point of a section of the paper

- Look at the remainder of the transition sentence. Is it providing some kind of gesture forward or introduction to new information?

Key Points: Revising Paragraphs

- Strong paragraphs are focused, developed, and coherent. There are activities (explained in this chapter) that you can try to help you find weaknesses in these areas.

- Make sure that your introduction and conclusion are aligned and that your conclusion doesn’t waste time summarizing a paper shorter than about 2000 words.

- Check transition sentences by making sure that the first sentence in each paragraph after the introduction includes a reference to ideas already covered and an introduction to new ideas to be explained in the paragraph that includes the transition.

Text Attributions

“Color Coding Topics: A Strategy to Strengthen Focus” was revised with the help of James Bushard, a student in my class during Spring 2022, who also provided the examples, including the example in “Rainbow Paragraphs.”

“Mapping Paragraphs: A Strategy to Strengthen Logical Coherence” was revised with the help of Lorenzo Locks Azeredo, a student in my class during Spring 2022, who also provided the example. The map provided is my recreation of his map.

A characteristic of writing in which the text stays on topic. This term applies to both full projects and to individual paragraphs.

A characteristic of writing that provides the reader with enough evidence and enough explanation to support the claim that the writer is making. This term applies to both full projects and to individual paragraphs.

A characteristic of writing that, when successful, moves the reader smoothly and logically from beginning to end. Students sometimes call this "flow." This term applies to both full projects and to individual paragraphs.

A sentence that summarizes the main point of a paragraph.

Material from sources other than yourself and your own experiences, as distinct from explanation, which is where you explain your own ideas (including your understanding of your sources). See also "explanation."

Material in which you explain your ideas, as distinct from evidence, which is material from outside sources. See also "evidence."

The controlling idea for an academic text, though some other kinds of texts may have such a statement, too. See also "working thesis statement."

Statements made in a conclusion that move beyond summary to invite your reader to think or do something different as a result of reading your work.

A sentence usually at the beginning of a paragraph that makes a connection between the ideas in the previous paragraph(s) and the idea in the next one. See also "transition."