Focusing Your Reading

Reading for your academic work differs from reading for pleasure. When you pick up that mystery novel or that article about last Sunday’s game, you’re reading for your own amusement, interest, and information. What you read may be useful, too, but you aren’t reading specifically to use material from the text. When you are reading for your academic work, you may be interested in the text, but your enjoyment is not a primary purpose.Your professor has assigned the reading, and they want you to get something out of that material.

Think about what the professor’s purpose could be and how you can use that to guide your reading so that it’s more efficient. Here are some of the common purposes for reading assignments in college:

- Are you going to be tested on that material? If so, what concepts or other information will you need to understand (and remember) as you read?

- Look over the syllabus to find out what kind of information will be on the relevant test and how this particular text fits into that unit.

- Make notes about the concepts and information that you should focus on. It can be particularly helpful to create these notes as you use pre-reading strategies.

- As you read, update those notes with specific information from the text.

- Are you going to write about that text? If so, what should you understand about the text and what evidence will you need to gather as you read?

- Read the assignment in advance to understand how the professor will be asking you to use the text.

- Make notes about the kinds of understanding and evidence you should be gathering before you start reading.

- As you read, update those notes with the actual information, evidence (including quotations and paraphrases), or other material you are finding.

- Are you supposed to make connections to other materials in the course?

- Read in advance any assignments that ask you explicitly to make connections. What kinds of connections is the professor asking you to make?

- Look at the other materials assigned in that unit. Where do you think connections might exist? Make notes about possible connections before you start reading.

- As you read, update those notes with the actual connections you are finding.

Of course, if you aren’t sure what the professor’s purpose is, you can—and should—ask. Asking for clarification can save you (and your classmates) lots of time and ultimately save the professor some frustration since you’ll be focusing on the aspects of the text that the professor wants you to.

Notice that in all of these, I’m suggesting that you make notes. Making notes as you read, which we’ll discuss more when we get to annotating in the next section, can save you time and help you focus your attention.

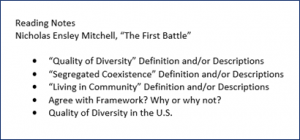

We’re going to use the assignment I introduced earlier, and here I’ll focus on the parts that are about Mitchell’s article.

Looking over the assignment, I have to understand what Mitchell means by “segregated coexistence” and “living in community,” since I need to apply those ideas to the article I pick. It would also be a good idea to understand what he means by “quality of diversity,” since I need to think about that for the last question about how this works in the United States.

While I don’t have to answer every bulleted question (I know this because I’m asked to “consider questions like”), I want to think about whether I agree with Mitchell’s framework or have ideas of my own. I also have to think about the connection between Mitchell’s ideas and the quality of diversity in the US.

Mining the assignment this way gives me a list of ideas to focus on as I read and take notes.

It’s your turn again. Using the article that you’ve chosen from the example assignment, create a list of what you will need to focus on as you read the article you have chosen.

Compare your list with one written by a classmate working on the same article. Talk through any differences in your lists so that you both end up with a stronger focus as you start reading.

Reflection After Reading: After you have read the article, reflect on how useful your list was in helping you stay focused on the professor’s purpose. What worked? What didn’t? What would you change, if anything, about how you created your list?

Between your pre-reading and your understanding of why the professor assigned the reading in the first place, your reading will be much more efficient.

Key Points: Focusing Your Reading

- Before you start reading, plan for what you should focus on.

- Be sure to use this information to take notes as your read.

- If you don’t know what the professor wants you to focus on, ask!