Chapter Six: Infancy

Cognitive Development in Infancy

“Children have real understanding only of that which they invent themselves, and each time that we try to teach them something too quickly, we keep them from reinventing it themselves.” Jean Piaget

The term cognitive development refers to the process of growth and change in thinking, reasoning and understanding. Infants develop cognitively through social interactions and exploring their world. Parents, teachers, friends and caregivers play a vital role in the cognitive development of infants. Infants who are raised by caring, responsive adults develop cognitively at a quicker rate. Infants are “born to learn” (National Research Council and Institute of Medicine 2000, 148) and they actively seek out opportunities in their environment to assimilate new information.

Piaget believed that assimilation and accommodation operate in very young infants. Cognitive changes are qualitative at each stage. Assimilation is incorporating new information into existing schemes. Accommodation is adjusting schemes to fit new information and experiences. Piaget believed that children actively construct their own cognitive worlds, and providing infants with a safe, stimulating environment to explore will encourage them to develop cognitively.

Object permanence is an important cognitive milestone. It is the understanding that objects and events continue to exist even when they cannot be seen, heard or touched. An example is a child playing with a stuffed bear. When the stuffed bear is hidden, the infant begins to look for it. She realizes the object exists even though it is out of her sight. When the stuffed dog is hidden, the infant begins to look for it. She realizes the object exists even though it is out of her line of sight. Infants understand movement from a very early age, and if you show them a toy that is moving in a line, then goes behind a wall or screen, they will automatically shift their gaze to the other side of the wall to anticipate that object reappearing there!

Factors that Impact Cognitive Development

Nutrition is extremely important in infancy. It affects physical development and cognitive development. Malnutrition limits cognitive development. A diet rich in protein and fat can have positive long-term effects in infancy. Infants need a diet high in fat to help their brains develop. The first year of life is not the time to put an infant on a diet. Fat feeds the infant’s brain. “The disparagement of dietary fat sometimes obscures the fact that children and adults need fat in their diets. It supplies essential fatty acids (EFA) and aids in the absorption of fat-soluble vitamins A, D, E and K. It is a substrate for the production of hormones and mediators. Fat, especially in infancy and early childhood, is essential for neurological development and brain function. Mother’s milk and infant formula supply 40–50% of their energy as fat.” (Fidler et al. 1998).

Universally, poverty presents a chronic stress for children and families that may interfere with successful adjustment to developmental tasks, including school achievement. Children raised in low-income families are at risk for academic and social problems as well as poor health and well-being, which can negatively impact educational achievement. (Hyson, 2014) Poverty can have a negative effect on an infant’s cognitive development, but early intervention programs can prevent this negative effect. Many low-income parents cannot provide an intellectually stimulating environment because they are spending most of their time making sure their basic needs are met. Early Intervention and Head Start programs can help infants get the support and stimulation they need to develop normally (Hyson, 2014).

Language

A key component of cognitive development is language development. Several theories have attempted to explain our species’ near-universal ability to learn spoken language, almost always in the absence of direct instruction. While most of our language development takes place after birth, there are important pieces of the puzzle that are laid down in utero. Components of spoken language:

- Phonology: the rules that govern the shared sounds of language; includes phones (the smallest units of sounds) and phonemes (the smallest units of sound that can signal meaning); example: hit and hat – four distinct phonemes: /h/, /t/, /i/ and /a/ – but the two vowels /i/ and /a/ are the distinct phonemes that change the word from hit to hat (approximately 45 phonemes in English)

- o This is the first step of language development for infants;

- o Attention to sound almost from birth – strong preference for language over other sounds in the environment; it is as if infants are born with a sense that it is important to pay attention to what people are saying

- o As motor skill develops and babies can control their tongues more readily, they will begin to mimic sounds they have heard in their environment, often practicing them over and over.

- o Typically, infants can make vowel sounds early on, as these do not require a lot of fine muscular control in the mouth (try it yourself – make the vowel sounds /a/ /e/ /i/ /o/ u/ and you will notice that it is only the shape of your mouth that changes.

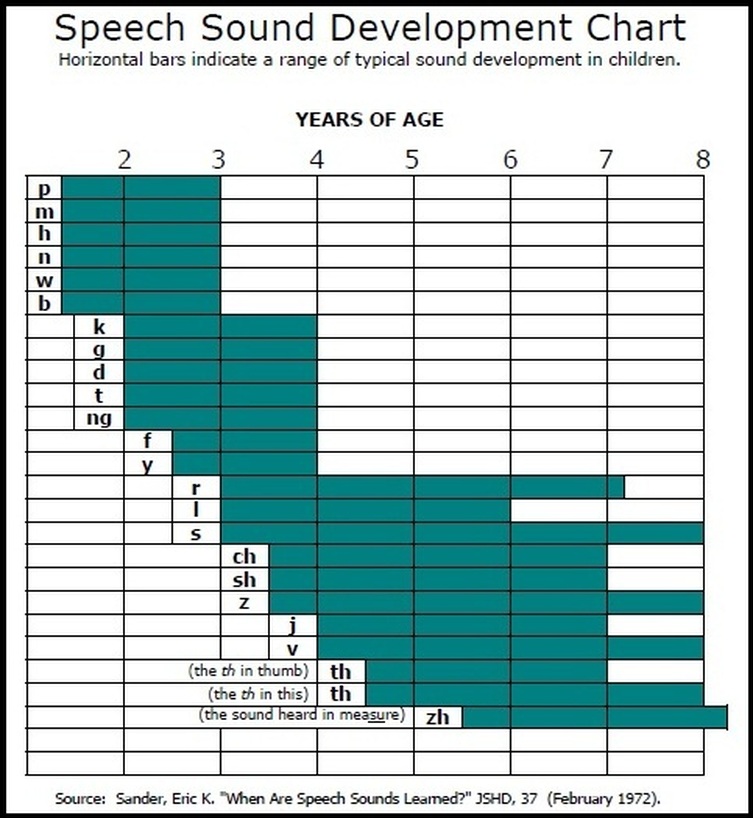

- o Usually, sounds that require less tongue control come first; back-to-front development in the mouth cavity “lip poppers” /b/ /p/ /m/, then sounds that involve tongue and front teeth /t/ /d/ , and then sounds that require specific control come later.

- o Typically blends (bl, cr, etc.) are the hardest, and they usually develop later in toddlerhood through preschool and even school age (Gordon & Browne, 2017; Santrock, 2013).

- Morphology – is the study of morphemes in a language. Morphemes are the smallest sequences of phonemes (units of sound) in a language that have meaning; for example, the /s/ at the end of a noun indicates that it is plural;

- o Theories of language development have their biggest challenge in describing how children develop morphological proficiency because there tends to be a common set of grammatical errors that children make that cannot be accounted for through experience

- Syntax – also known as grammar; the syntax of a language is the set of rules that determine word-order in sentences, grammatical correctness, and the acceptability of words, phrases, and clauses.

- o This develops in a regular pattern: toddlers move from one-word utterances (holophrase hypothesis) to two (telegraphic speech), then three- and four-word utterances, all of which can have a range of meanings (often interpreted by caregivers through the context and non-verbal language of the child)

- Semantics – the set of rules that govern the meaning of words and phrases; semantics bridges the gap between our perception of reality and the way we talk about that reality

- o There are socially shared meanings of every word: dog, car, bird, running, taxes, etc.

- o Semantic development entails learning the varied meanings of words and then also understanding how those meanings are related to the reality the speaker is trying to share (Gordon & Browne, 2017; Santrock, 2013)

- Pragmatics – the intentional use of language to achieve specific outcomes; this can include the purposeful breaking of the rules of phonology, morphology, syntax, or semantics to make a point, or produce an outcome (action or thought); because pragmatics is related to the context of spoken language, it is sometimes considered the overarching organizing principle of language (Owens, 27)

- o Even with single word utterances from toddlers, we can see evidence of language pragmatics: any caregiver can tell you there are several interpretations of the word “cookie” from a 2-year-old- “I want a cookie.” “Do we have any cookies.” “I see a cookie.” I see Cookie Monster. Is that a cookie you have? Etc.

- o Pragmatics helps us learn how to lie – and that is not a bad thing. Although many parents are dismayed when they discover that their toddler has started to lie, in many ways this behavior is a positive sign of healthy cognitive and linguistic development! In order to lie, the speaker needs to have a working proficiency in the rules of spoken language, especially semantics; they also must have the ability to talk about things that are not physically present or may not have ever been present; and they must be able to effectively consider the knowledge and thoughts of the person they are lying to. This is not easy to do (as we all know – sometimes it works, and sometimes it does not!)

Language Development Models

The models that seek to explain language development are not that different from the models used to explain most other aspects of human development. They all can be reduced to one of three sources for developmental input: Nature, Nurture, or a mix of the two. What makes theories of language development particularly interesting are the fact that spoken language development – unlike many other things – is universal across cultures and geographical locations, and the near impossibility of testing any one theory using truly experimental methods. Instead, these theories have been informed by careful observation and quasiexperimentation across language users.

Behavioral Theories

Behavioral Theories of language are firmly based in the “nurture” camp of developmental theories. The basic premise of this theory stems from B.F Skinner’s theory of operant conditioning, which states that all behavior is learned and modified through the consequences of that behavior – either a reward or a punishment. According to behavioral theories, learning language is no different from any other learning in childhood.

Language is learned through a series of reinforcements or corrections by more competent speakers, typically parents and other adults. In this model, the child attempts an utterance which is then either confirmed by the adult to reinforce the speech behavior or corrected by the adult to modify it.

For example, imagine a child who is given a ball:

| If the child says: | Then the adult will respond: | And the outcome will be: |

| Ball! | That’s right! It’s a ball! | The behavior is confirmed and will be repeated |

| Apple! | No, that is not an apple; it’s a ball. | The behavior is weakened and is less likely to be repeated. |

According to the behavioral model of language acquisition, this is how language development proceeds, with each language behavior being either strengthened or weakened through feedback from a competent speaker. There are certainly examples of language development where this happens, and there is evidence that parents and other caregivers routinely correct children’s language production in this manner. However, this theory alone cannot explain the rich variety of language use in early childhood. One of the main criticisms of this theory is that it cannot explain two of the most intriguing elements of language development: how quickly it happens, and how children can say things they have never heard before. If language were behaviorally conditioned, it would take an entire lifetime for children to develop proficiency in spoken language since every component would have to be learned through trial-and-error with competent feedback. Instead, children become competent speakers of their native languages in an average of five years. During that time, they also say many things they have never heard before, including made-up words [like goed for went], incorrect pronunciations of real words, and completely novel sentences (and sometimes whole stories!) In short, behavioral theories explain one aspect of how competent speakers help the language development process along by giving real-time feedback, but they can’t explain most of language production in early childhood.

According to the behavioral model of language acquisition, this is how language development proceeds, with each language behavior being either strengthened or weakened through feedback from a competent speaker. There are certainly examples of language development where this happens, and there is evidence that parents and other caregivers routinely correct children’s language production in this manner. However, this theory alone cannot explain the rich variety of language use in early childhood. One of the main criticisms of this theory is that it cannot explain two of the most intriguing elements of language development: how quickly it happens, and how children can say things they have never heard before. If language were behaviorally conditioned, it would take an entire lifetime for children to develop proficiency in spoken language since every component would have to be learned through trial-and-error with competent feedback. Instead, children become competent speakers of their native languages in an average of five years. During that time, they also say many things they have never heard before, including made-up words [like goed for went], incorrect pronunciations of real words, and completely novel sentences (and sometimes whole stories!) In short, behavioral theories explain one aspect of how competent speakers help the language development process along by giving real-time feedback, but they can’t explain most of language production in early childhood.

Psycholinguistic Models of Language Development

On the opposite end of the nature-nurture spectrum is the psycholinguistic-syntactic model of language development. In this family of theories, the underlying assumption is that language development must be driven by some innate, biological force – possibly even a physical structure in the brain. This theory attempts to explain how language acquisition can be universal among all humans even if the languages we learn can vary so much. There are thousands of languages spoken on this planet, and we can learn any one of them!

When trying to explain human universals, most of the time a biological explanation is helpful because it works around cultural differences. Adding in the possibility of an innate structure in the brain designed specifically for language acquisition is also helpful; it provides an explanation for how quickly young children learn the sounds and rules of spoken language, which can be extremely complicated. One early version of the psycholinguistic theory of language development was proposed by Noam Chomsky. He theorized that infants were born with a specific area or module in the brain, called the Language Acquisition Device (LAD), that was there specifically to ensure the development of spoken language. The LAD was described as a universal, genetic attribute that allowed anyone to learn any language and helped explain many of the gaps in the behavioral model.

The LAD would be like a switchboard, with individual switches for phonemes, morphemes, and syntax. At birth, the infant’s brain starts immediately listening for language input in the environment – people talking. What the infant hears helps the LAD decide which way to flip a switch. For phonemes, if certain sounds are never heard, those switches do not get turned on. With syntax, hearing sentences spoken helps the LAD determine that it should be set to a subject-verb-object word order for English and not a subject-object-verb order, as in Korean.

Although this theory helps fill in many of the gaps in other models, it still falls short of being able to explain the range of situations in which language is developed. Plus, increasingly refined techniques for viewing the brain in action, such as functional MRI, have failed to show any evidence for the LAD as described by Chomsky. Instead, it seems that language development is another example of nature AND nurture, not versus.

Sociolinguistic Models

At the halfway point between nature and nurture lie the sociolinguistic models of language development. As you probably already have guessed, this family of theories recognizes that while the brain structure is important – after all, there are specific areas of the brain that process and create language – human interaction is also essential.

From the second chapter of this book, you should recall Vygotsky’s theory and the emphasis he placed on the balance between children’s internal cognitive development (what they are ready to do independently) and the challenge that can be provided by the environment (what children can do with help). Sociolinguistic models are like this. These models recognize that large parts of language acquisition are socially supported, particularly semantics and pragmatics. This makes sense; these are the two aspects of language that are most necessary for social interaction. Semantics, or word meanings, need to be socially shared for words to make sense. Imagine if we all used a different word for mayonnaise – ordering a sandwich would be an interesting surprise every time! Pragmatics is how we use language to create shared thoughts and emotions, and to get people to do what we want them to. For example, saying “I don’t want mayonnaise on my sandwich” when a friend gets out the

Miracle Whip tells them what you really mean is “That’s gross!”).

Researchers into language development now routinely assume that language acquisition is a balance of nature and nurture. Yes, most children will learn spoken language just by being around people who are talking, which means there must be some strong, internal force that guides the brain to pay attention and develop this ability. However, stories of children who are not exposed to spoken language and are never able to learn it later in life give good evidence for the deep need for social interaction; hearing it at a distance is not enough – infants and babies need to be a part of the social interactions in which language is used. These findings give compelling evidence that language acquisition is both nature and nurture!

Language Development from Conception through Birth

The womb is not soundproof. The developing fetus hears muffled versions of the sounds of the outside world – none so clearly and regularly as the sounds of the mother’s speech. As the fetal brain develops, it is stimulated by these sounds and becomes accustomed to hearing specific voices and sounds, which the newborn will actively respond to once out and about in the world.

During gestation, the areas of the brain which will later become adept at processing and producing language are just developing, using the ambient sounds of the environment as early input.

Recall from the chapter on Brain Development that some neural networks are “experience expectant.” In that chapter, we discussed the visual system, and how infants are born with the basic framework but need input from the environment to complete the development of those neural pathways. It is possible that language is a similar system, where the neural foundation is laid during gestation with some ambient input, but the system is not fully functional until a significant amount of language experience takes place after birth.

Language Development from Birth to 15 months (Infants)

Infants’ and toddlers’ effortless development of spoken language has led to several theories seeking to explain how this acquisition occurs, and which environmental or innate features drive the development.

Skinner and the other Behaviorists were not entirely wrong when they claimed that children learn language from competent adults, and that it is through a system of feedback that children refine their language use. Although this theory cannot explain everything about language acquisition, it does help us to understand the importance of some of the earliest language that children are exposed to.

Conversational Patterns

If you have ever spent time with a pre-lingual baby, you have probably engaged in the critical practice of patterning conversation – and you probably did it without even realizing that you were engaging in a major developmental process. As babies begin to babble, they not only start to experiment with the phones of the languages they hear, but also with the intonations and speech patterns of the speakers around them. Mothers, fathers, and other caregivers are important first models not just for the sounds of speech, but also for the back and forth of conversation.

It is a common Western practice for adults to “talk” to babies long before the infant can respond in conventional speech, yet in these conversations the babies often do a lot of the talking! Caregivers, parents, and other adults frequently engage in the practice of modeling by responding to babies’ speech as if it were in fact comprehensible language, and then taking turns to allow the baby to “talk” more. Imagine the quite common scenario of a parent making dinner while the infant rests in a bouncy chair on a nearby countertop or in a swing. The baby babbles away, watching the parent prepare dinner. As the baby pauses in speech, the parent takes the opportunity to “respond” to what the infant has been “saying.” Perhaps the parent describes what he is doing or agrees with the baby– “You’re right, we should have added more garlic!” The parent then pauses, giving the baby a chance to babble another “response” in the conversational chain, to which the parent again replies. This time the parent asks a question (“Do you think the puppy would like these scraps?”) or disagrees with what the baby has said (“Oh, I don’t know – that seems like a lot of cheese for one person…”) and so on, in

direct response to the inflection, volume, or facial expressions of the baby as she “talks.”

These episodes of modeling conversation are essential for helping infants figure out not only what the sounds of their language are, but also how language can be used between two people. In each exchange, the infant is exposed to a repetition of the phonemes of the language around her, helping her brain to narrow down the range of possible sounds that can be speech. This also helps the infant to more reliably mark the boundaries of words and phrases. Finally, this provides critical information about the patterns of discourse, including how users share conversational responsibilities (if you pause, then it is my turn to talk).

Although we tend to think of language as a cognitive process, it has a very real set of physical constraints. As newborns, babies’ brains are already tuned in to the language around them, and they quickly begin to pick up sounds in their environment. It does not take long before infants are trying out those sounds, babbling away to themselves while their parents are trying to get them to go to sleep! Over hours of practice, infants become increasingly adept at forming sounds, at imitating speech patterns, and at attempting individual words. But as all of that is happening, there is a lot of physical growth that must also occur. At birth, an infant’s tongue is disproportionately large for the mouth, and the musculature that is necessary for speech hasn’t developed fully. But over the course of the first year of life, these physical barriers to speech are resolved and by the time they are a year old, most babies have one or two words they produce reliably along with a diverse collection of almost-words that are the baby’s developing attempts at spoken language.

How does language develop in infancy? Crying is present at birth. It signals distress. Cooing begins at about 1 to 2 months. Babbling occurs in the middle of the first year. (Ma Ma, Da Da) Gestures begin at about 8 to 12 months. This is about the same for children who can hear and children who are deaf. From birth to 6 months, infants are “citizens of the word”. They recognize most sound changes in any language. After 6 months, infants learn their own language and gradually lose the ability to recognize sound changes in other languages.

The first words occur between 10 to 15 months. The holophrase hypothesis states that there is a time when infants say one word that implies a whole sentence. (For example, “juice” means “I would like some juice in my sippy cup.”) Infants understand about 50 words at 13 months (receptive language) but they are unable to say them until about 18 months (spoken vocabulary).

Children have a huge amount of growth in language from 18 months to 2 years. This is called the vocabulary spurt. They speak 50 words at 18 months and 200 words at two years. Toddlers use short and precise two-word utterances to communicate–telegraphic speech. Biology influences language development. Human language is about 100,000 years old and is strongly influenced by biology. The vocal apparatus has evolved over the years. The brain plays a large role in language development. Aphasia is brain damage that involves a loss of ability to use words. Broca’s area is the brain’s left frontal lobe that directs the muscle movements involved in speech production. Wernicke’s area is in the brain’s left hemisphere. It is involved in language comprehension.

Noam Chomsky believes that humans are biologically prewired to learn language. Children are born with a language acquisition device (LAD), a biological ability to learn language. Children all over the world reach language milestones at the same time.

However, there is a critical period for learning language. One of the most famous examples of this is the story of Genie, a girl who suffered severe emotional abuse and neglect. She was kept in a closet for many years and was never spoken to. At age 14 she was finally rescued and placed in a loving home with many people working together to help her. Even after years of professional interventions she was never able to progress past the stage of toddler speech. She had passed the critical period and was stunted in her growth. She was only able to learn to speak 50 words and was unable to combine them into full sentences.

Preschoolers experience rapid language learning. Critics argue that learning continues beyond preschool. The behavioral view states that language is a complex skill which is learned and reinforced. Biology cannot explain creativity or the orderliness of language; individual differences exist.

Environmental influences impact children’s language development as well. Parents’ talkativeness, vocabulary and level of language is linked to children’s vocabulary growth. Parents often use child directed speech. This is spoken in a higher pitch than normal with simple words and sentences. It holds an infant’s attention and maintains communication.

Other strategies used to encourage infant speech include recasting, rephrasing what a child says, expanding, adding more sophisticated vocabulary to what a child says, and labeling, assigning and identifying objects by name.

Parents can stimulate infants’ language development by being an active conversational partner, talking as if an infant understands what you are saying, and using a comfortable language style.

Parents can stimulate toddlers’ language development by being an active listener, using comfortable language while expanding language abilities, avoiding sexual stereotypes, and resisting making comparisons.

The interactionist view of language development states that biology and sociocultural experiences contribute to language development. Parents and teachers construct a language acquisition support system. Children acquire native language without explicit teaching. Children learn by modeling their parents’ language.

Imitation

Imitation is a powerful way for children to learn. Newborns love to imitate facial expressions and vocalizations. Through reciprocal socialization, adults interact with infants and infants learn to respond back by imitating what they have seen/heard. Infants engage in both immediate imitation and delayed imitation. When a parent sticks out their tongue and the infant responds by doing the same, this is an example of immediate imitation. When an infant covers a doll with a blanket a few hours after watching her parent do so, that is an example of delayed imitation. Children imitate the language that they hear. Being raised in a language-rich environment allows the infant to imitate the wide range of words they are exposed to.

Memory

The capacity to remember things an infant has been exposed to allows them to learn language, interact with familiar adults and understand how objects work. As infants get older, they can remember information for longer periods of time.

Media Attributions

- Speech Sound Development Chart © Eric K. Sander is licensed under a All Rights Reserved license

- Baby and ball © Pixabay is licensed under a CC0 (Creative Commons Zero) license

Media Attributions

- Speech Sound Development Chart © Eric K. Sander is licensed under a All Rights Reserved license

- Baby and ball © Pixabay is licensed under a CC0 (Creative Commons Zero) license

incorporating new information into existing schemes

adjusting schemes to fit new information

one word implies a whole sentence

two word toddler speech