Chapter One: Perspectives on Early Childhood

Historical Perspectives

History of Childhood

Throughout Ancient Times, the Middle Ages, and most of Early Modern History, the idea of childhood as we understand it today didn’t exist. In part because of the hardships of life in general, and in part because of very high infant and child mortality rates (primarily due to malnutrition, disease, and general lack of access to medical care), the way families viewed childhood was fundamentally different from the way it is viewed now.

Before the 16th century, the focus of families was on survival. A child’s value was in their ability to contribute toward that goal. It wasn’t until the late 1500’s that the idea of a need for education of the common man emerged. Until this point, it was primarily only those who intended to enter the clergy or become government officials or physicians who received any kind of formal education. As societies developed and progressed, they began to recognize the value of developing a skilled workforce. As a result, families began to need support in providing an education for their children, and the first of what could be recognized as modern schools were established.

It had been widely believed that until modern times, children were primarily treated with indifference, dealt with harshly, and regarded as miniature adults. This argument, which was famously made by French historian Philippe Ariès (1914–1984) in his 1960 book titled, Centuries of Childhood, has since been disputed. Ariès came to this conclusion after studying historical writings about childhood (or lack thereof) and paintings depicting children through the Middle Ages. However, it is now understood that the depiction of children in pre-18th century art as miniature adults was not at all due to any lack of regard or affection parents had for their children. According to Alastair Sooke, in his article for the BBC, “How Childhood Came to Fascinate Artists”, Ariès’ thinking was flawed for two key reasons:

Pictures of children were surprisingly rare during the late Middle Ages and even into the 16th Century. In those days, the infant Jesus was the principal image of childhood in art. For another, when artists finally started to paint children with greater frequency during the 17th Century, they did so in a way that seems unnatural to modern eyes, by presenting them as miniature adults. (Sooke, 2016)

He goes on to explain that paintings of the children of nobility (because they were the only ones who could afford to have their portraits painted) served a different purpose than snapping a photo of a child today; it was not meant to capture a moment in time. Rather, children were often dressed and posed as adults in an effort to depict their parents’ hopes for the person they would become. For royalty, these portraits became important advertisements to potential suitors. It was, in reality, a very early form of the personal profile.

Our current notions of childhood are primarily rooted in the works of 17th-century English philosopher John Locke and of 18th-century Swiss philosopher Jean Jacques Rousseau.

Locke (1632-1714) is probably most famous for his notion of children coming into the world as a tabula rasa, a Latin term translated as “blank slate”. He believed that infants were neither inherently good nor inherently evil (as was commonly believed at the time—a reference to the church’s teachings of original sin) but rather were neutral or “blank”. A child’s nature and personality would develop over childhood, during which time he believed a child was particularly impressionable and sensitive to new experiences. Because he believed that children were born with no set predeterminations and since the child’s mind was so malleable, an adult could mold him or her with careful diligence. Many of his ideas about education endure today, most notably:

- Each person develops according to his or her unique experiences, and thus the need for individualized education

- Learning should be enjoyable, with many opportunities for play

- Educators should focus on teaching critical thinking skills

- Children learn best through sensory experiences

Rousseau’s (1712-1778) philosophy of education emphasizes the development of a child’s character and moral sense. The goal was for the child to learn to remain principled and honorable, even in the unnatural and imperfect society in which the child would have to live. He also believed that children should learn through exploration and experiences carefully led by adults. This philosophy was predicated upon the idea that children were born inherently good, not inherently wild or evil (or even neutral, as Locke believed). This was all very radical thinking for the time.

Some of Rousseau’s ideas that continue to influence education today are:

- Teaching should be flexible and responsive

- Children learn best from hands-on experiences

- Children’s thinking is different from adults’

- Children go through distinct phases of development

Locke and Rousseau helped to pave the way for what we consider our modern ideas about education. Many other early educational pioneers used Locke’s and Rousseau’s groundbreaking work as the foundation for even more progressive ideas about childhood and education. Examples include:

- Integrated curriculum and the need for educating the whole child (the belief that all aspects of human growth and development are interrelated)—Johann Pestalozzi

- Expansion of education to infants and toddlers—Robert Owen

- Play as the most important construct for learning, and the importance of creating play experiences that reflect the natural world in which children live. These ideas became the foundations for kindergarten— Freidrich Froebel

- Child-centered education and intentional teaching—John Dewey (Sooke, 2016)

Emerging Themes

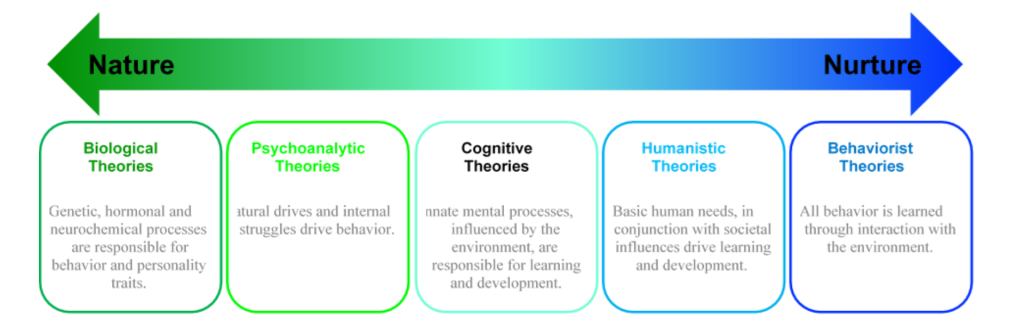

Nature and Nurture

As we reflect on these ideas about childhood throughout Western history, we see that distinct themes of development begin to emerge. Probably the most well-known is the theme of nature vs. nurture. This refers to the debate within developmental psychology concerned with examining whether certain characteristics and aspects of behavior are primarily the result of biological programming and inheritance (nature) or whether they are learned and the product of experience (nurture). Proponents of the nature view of development believe that humans develop based on a predetermined genetic plan that we inherit from our parents. Examples of this thinking can be seen, perhaps most famously, in the work of Charles Darwin and his theories of evolution, but also in later theorists such as Arnold Gesell (Bee & Boyd, 2009; Berk, 2017; Childhood defined, n.d.).

Proponents of the nurture view of development believe that humans develop based on the influences and experiences we collect over our lifetime, regardless of genetic makeup. Some of the most enduring theories of the nurture view of development stem from the works of John Watson, B.F. Skinner and Albert Bandura, whom we’ll explore in chapter two.

As Dr. David Rettew explains in his post “Nature Versus Nurture: Where We Are in 2017” for Psychology Today:

Today, most scientists who carefully examine the ever-expanding research base have come to appreciate that the nature and nurture domains are hopelessly interwoven with one another. Genes have an influence on the environments we experience. At the same time, a person’s environment and experience can directly change the level at which certain genes are expressed (a rapidly evolving area of research called epigenetics), which in turn alters both the physical structure and activity of the brain. (Rettew, 2017)

Embedded in the debate over nature and nurture are notions of stability and change— that is, ideas about how changeable and/or prone to influence, development and behavior are—as well as notions of universal vs. individual development. These debates seek to answer questions such as:

- Can patterns of behavior change?

- Can certain genetic and/or environmental influences be overcome?

- What accounts for individual differences in development?

- Why does human development seem to follow certain universal, predictable patterns?

Continuous and Discontinuous Development

Another debated controversy in the field of human development is the idea of continuous vs. discontinuous sequences of development. Continuous development refers to the idea that development occurs as the result of a continual maturation process—a steady unfolding of changes throughout the lifetime. This type of development can be thought of as similar to that of a tree. The organism (in this case, a tree) gradually develops and changes over time, but maintains the same primary characteristics and functions as it did before—just larger and more complex.

Discontinuous development refers to the idea that development occurs in distinct stages, each stage being fundamentally different from the preceding or following stages. This type of development is similar to that of a butterfly. At each stage of a butterfly’s life (egg, caterpillar, chrysalis, adult), the butterfly is very different from any other stage, and yet it is still a butterfly (Bee & Boyd, 2009; Berk, 2017; Childhood defined, n.d.).

In Chapter Two, we will explore more deeply how theories of development can fall into these categories of being either continuous or discontinuous.

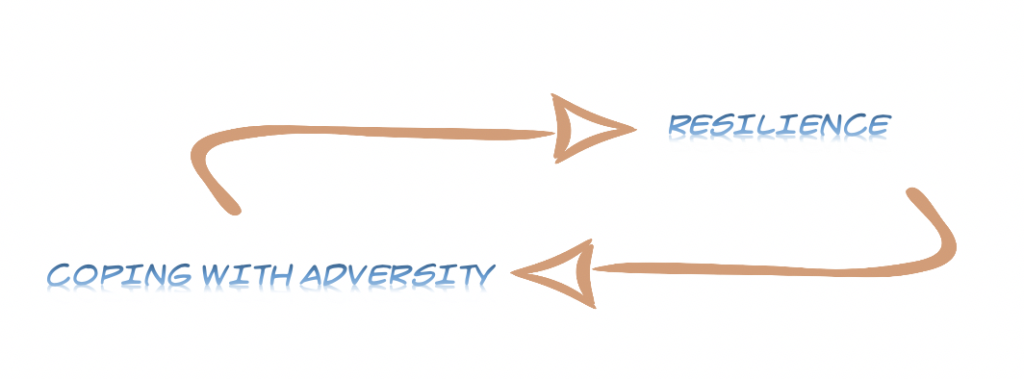

Risk and Resilience

A more contemporary debate that has arisen around educating and caring for children has to do with how we view risk and resilience. Conventional wisdom dictated that it was in children’s best interests to try to limit (as much as possible) their exposure to any form of adversity or loss. While most agree that it is, in fact, in children’s best interests to protect them from any kind of trauma, tragedy, threat, or significant stress, in recent decades, it seems that the pendulum has swung too far in the direction of insulating children from any and all forms of stress and loss. However, it is through this stress and loss that children learn to cope with future stress and loss, thus becoming resilient. Rather than using the everyone-gets-a-trophy strategy of rewarding children, we have come to understand that genuine and authentic praise serves children much better. It’s important to keep in mind that resilience is not a trait that people either have or do not have. It involves behaviors, thoughts, and actions that can be learned and developed. When children experience adversity—whether it be the loss of a parent or not making the team—helping them to frame the experience as one they can survive helps them for the next encounter. It becomes a positive feedback loop; adversity helps children to learn resilience, which then helps children to be more resilient in the face of future adversity. The key is in helping them learn effective coping strategies and supporting them through the resilience process. The American Psychological Association provides more information in their publication, “Resilience Guide for Teachers and Parents”, which can be found on their website (APA, 2012).

Media Attributions

- Bianca degli Utili Maselli, holding a dog (c. 1565–1614) © Lavinia Fontana, Public domain, via Wikimedia Commons is licensed under a Public Domain license

- Children’s Games (c. 1560) © Pieter Brueghel the Elder, Public domain, via Wikimedia Commons is licensed under a Public Domain license

- Nature vs Nurture diagram © Deirdre Budzyna via. ROTEL is licensed under a CC BY-SA (Attribution ShareAlike) license

- Discontinuous development © Wikimedia and Public Domain images . net is licensed under a CC BY-SA (Attribution ShareAlike) license

- Risk and Resilience © Deirdre Budzyna via. ROTEL is licensed under a CC BY-SA (Attribution ShareAlike) license