Chapter One: Perspectives on Early Childhood

How is Child Development Studied?

Researchers use three primary methods in studying development in order to draw their conclusions:

- longitudinal studies

- cross-sectional studies

- case studies

Longitudinal Studies refer to studies in which a large group of children is studied over time in order to look at specific changes that occur. Longitudinal studies may examine a single aspect of development or multiple aspects at once. Data is collected at two or more different time intervals, but typically the study looks at development multiple times over the course of several months or even over an entire lifetime. While some of the most valuable data about development has been gained through the use of longitudinal studies, because these studies are so comprehensive and lengthy, they tend to be very expensive to carry out and can take decades to be able to draw any concrete conclusions. Ultimately, longitudinal studies aim to draw conclusions that can be generalized over a population.

Cross-Sectional Studies refer to studies in which comparisons are made in the abilities and behaviors of two or more groups of children, each group being of a different age; for example, comparing the language skills of two-year-olds to the language skills of five-year-olds in order to come to some conclusion about the changes that occur between the ages of two and five. An advantage of this type of study is that it is typically less costly to carry out because the studies can be held over a very short timeframe—researchers don’t have to wait for children to get older. A drawback to these studies is that researchers are comparing more apples to oranges, rather than apples to apples.

Case studies refer to investigations in which a single child or small group of children are studied. Case studies are far more in-depth and detailed than longitudinal studies, include the related contextual conditions in which development is observed, and draw upon data from multiple sources. Because case studies apply only to a single or very small group of individuals, the results typically cannot be generalized to a larger population (Berk, 2017; Crain, 2011).

When looking at data from various types of studies, it’s essential to understand the difference between a correlation and a causation. Notable market analyst, Ben Yaskovitz, describes the difference as, “Correlation helps you predict the future, because it gives you an indication of what’s going to happen. Causality lets you change the future.” (Yaskovitz, 2013)

Correlation describes the relationship among two or more variables that appear to be related to one another, but one does not necessarily cause the other to occur. For example, there is a correlation between ice cream consumption and drowning (Yaskovitz, 2013). It seems that ice cream consumption rises and falls with the rate of drownings. However, there is nothing about eating ice cream that causes people to drown. In this case, it seems that there is another factor involved—weather. In certain climates and during certain seasons, people tend to consume more ice cream. More people in those climates and during those seasons tend also to be engaged in water -related activities, and the more people involved in water-related activities, the more drownings that tend to occur. The two factors are related but one does not cause the other to happen.

A more famous mistaken correlation was that between unpleasant odors and disease. Until the late 19th century, before people fully understood microbiology and disease processes, it was believed that bad odors actually caused disease—unpleasant-smelling air appeared to make people sick, so the two occurrences were correlated. Of course, we now understand that it’s not the odor that makes people sick, but rather the factors leading to the odor that do. (ex. It’s not the smell of spoiled milk that will make you sick, but the bacteria in the milk that produces the smell that will.)

Causation describes a relationship among two or more variables in which one occurs as the direct result of another. One thing causes another. For example, the way that gravity causes things to fall toward the ground.

Even in the field of child development, there have been many examples of occurrences in which a correlational relationship was mistaken for a causational one; it’s critical to recognize the difference between the two when drawing conclusions about children’s development and behavior (Santrock, 2013).

Did you know…

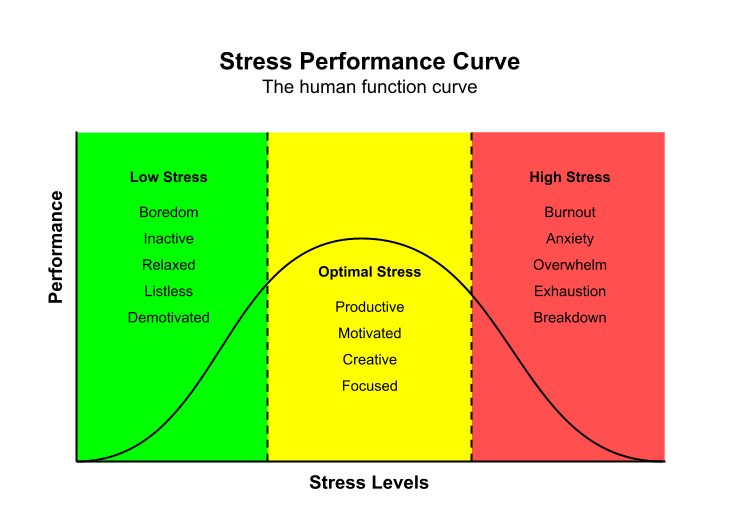

A little stress can actually be good for you? Studies show that with a little bit of stress, people actually have improved performance on various tasks. We seem to work better when we are under just the right amount of pressure to succeed. A little stress helps to keep us focused and motivated, but too much can tip the scales and we can find ourselves fatigued, anxious, or even burnt out. Keep this in mind as you progress throughout this course and also as you work with children—it’s healthy to strive for success and to be slightly out of your comfort zone. The graph below helps to illustrate this phenomenon.

Media Attributions

- Stress Performance Curve © Doris Buckley via. the ROTEL Project is licensed under a CC BY-NC-SA (Attribution NonCommercial ShareAlike) license

refer to studies in which a large group of children is studied over time in order to look at specific changes that occur

refer to studies in which comparisons are made in the abilities and behaviors of two or more groups of children, each group being of a different age

refer to investigations in which a single child or small group of children are studied. Case studies are far more in-depth and detailed than longitudinal studies, include the related contextual conditions in which development is observed, and draw upon data from multiple sources.

describes the relationship among two or more variables that appear to be related to one another, but one does not cause the other

describes a relationship among two or more variables in which one occurs as the direct result of another. One thing causes another.