Chapter Two: Theorists and Theories of Development

Other Contemporary Theories to Consider

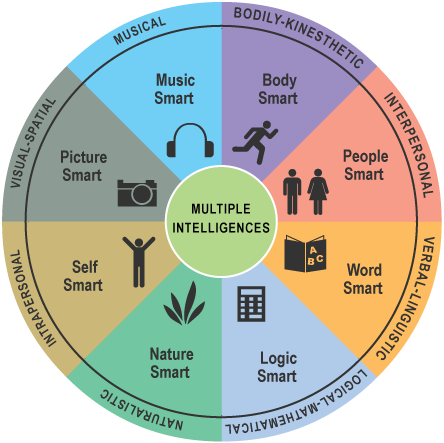

Theory of Multiple Intelligences

Howard Gardner (1943- ) contends that previously accepted ideas of human intellectual capacity are all based on the belief that intelligence is fixed throughout one’s lifetime and that intelligence can be measured through an individual’s logical and language abilities. Gardner’s theory challenges this traditional, narrow view of intelligence. According to Gardner’s theory, intelligence encompasses the ability to create and solve problems,as well as create products or provide services that are valued within a culture or society. His original theory proposed seven separate intelligences. He has since revised this thinking and has added an eighth intelligence, and a proposed ninth intelligence that has yet to experience full acceptance. The nine intelligences are Verbal/Linguistic, Logical/ Mathematical, Visual/Spatial, Bodily-Kinesthetic, Musical, Interpersonal, Intrapersonal, Naturalistic, and Existential. Key tenets of Gardner’s theory are

- All human beings possess all nine intelligences in varying degrees.

- Each individual has a different intelligence profile.

- Education can be improved by assessment of students’ intelligence profiles and designing activities accordingly.

- Each intelligence occupies a different area of the brain.

- The nine intelligences may operate in consort or independently from one another.

- These nine intelligences may define the human species (Armstrong, 2018; Gardner, 1999; Gardner, 2006).

The Nine Intelligences

Verbal/Linguistic intelligence refers to an individual’s ability to understand and manipulate words and languages. Everyone is thought to possess this intelligence at some level. This includes reading, writing, speaking, and other forms of verbal and written communication. Traditionally, linguistic intelligence and logical/ mathematical intelligence have been highly valued in education and learning environments.

Logical/Mathematical intelligence refers to an individual’s ability to do things with data: collect and organize, analyze and interpret, conclude and predict. Individuals strong in this intelligence see patterns and relationships. These individuals are oriented toward thinking: inductive and deductive logic, numeration, and abstract patterns. This is the kind of intelligence studied and documented by Piaget.

Visual/Spatial intelligence refers to the ability to form and manipulate a mental model. Individuals with strength in this area depend on visual thinking and are very imaginative. People with this kind of intelligence tend to learn most readily from visual presentations such as movies, pictures, videos, and demonstrations using models and props. They like to draw, paint, or sculpt their ideas and often express their feelings and moods through art. These individuals often daydream, imagine and pretend.

Bodily/Kinesthetic intelligence refers to people who process information through the sensations they feel in their bodies. These people like to move around, touch the people they are talking to and act things out. They are good at small and large muscle skills; they enjoy all types of sports and physical activities. They often express themselves through dance.

Musical intelligence refers to the ability to understand, create, and interpret musical rhythm and tones, and the capability to compose music. Composers and instrumentalists are individuals with strength in this area.

Interpersonal Although Gardner classifies interpersonal and intrapersonal intelligences separately, there is a lot of interplay between the two, and they are often grouped together. Interpersonal intelligence is the ability to interpret and respond to the moods, emotions, motivations, and actions of others. Interpersonal intelligence also requires good communication and interaction skills, and the ability to show empathy toward the feelings of other individuals. Counselors and social workers are professionals that require strength in this area.

Intrapersonal intelligence, simply put, is the ability to know oneself. It is an internalized version of interpersonal intelligence. To exhibit strength in intrapersonal intelligence, an individual must be able to understand their own emotions, and motivations, and be aware of their own strengths and weaknesses. It’s important to note that this intelligence involves the use of all others.

Naturalistic intelligence describes the ability to both identify and distinguish between different types of things found in the natural world. Naturalistic thinkers are people who value order and notice relationships and patterns.

Existential Intelligence encompasses the ability to pose and ponder questions regarding existence—including life and death. This would be in the domain of philosophers and religious leaders (Armstrong, 2018; Gardner, 1999; Gardner, 2006).

Although Gardner’s theory was not originally designed for use in a classroom application, it has been widely embraced by educators and enjoyed numerous adaptations in a variety of educational settings. Teachers have always known that students had different strengths and weaknesses in the classroom. Gardner’s research was able to articulate that and provide direction as to how to improve a student’s ability in any given intelligence.

Match the terms on the left column with the correct definitions on the right.

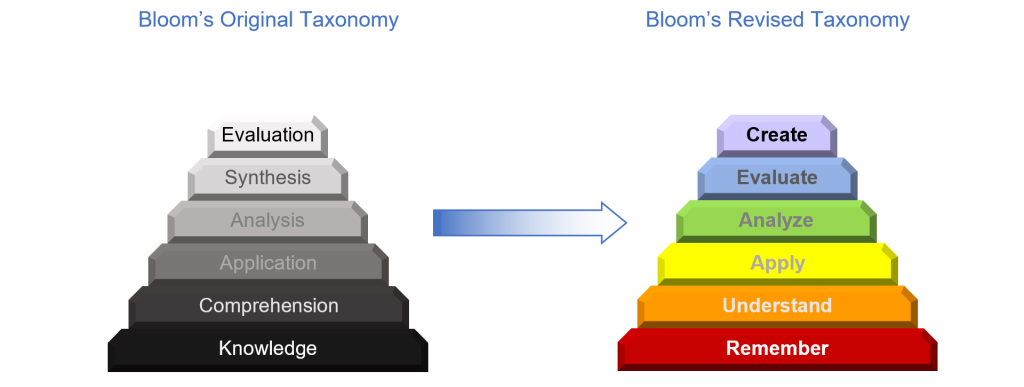

Bloom’s Taxonomy

Benjamin Bloom (1913-1999) was an influential psychological researcher and child activist. In 1956, Bloom, with collaborators Max Englehart, Edward Furst, Walter Hill, and David Krathwohl, published a framework for categorizing educational goals: The Taxonomy of Educational Objectives. Familiarly known as Bloom’s Taxonomy, this framework has been applied by generations of K-12 teachers and college instructors in their teaching.

The framework devised by Bloom and his collaborators consisted of six major categories of goals, in order of complexity: Knowledge, Comprehension, Application, Analysis, Synthesis, and Evaluation. Those categories after Knowledge were presented as “skills and abilities,” with the understanding that knowledge was the necessary precondition for putting these skills and abilities into practice.

In 2001, a group of cognitive psychologists, curriculum theorists, instructional researchers, and testing and assessment specialists published a revision of Bloom’s Taxonomy with the title A Taxonomy for Teaching, Learning, and Assessment. This title draws attention away from the somewhat static notion of “educational objectives” (in Bloom’s original title) and points to a more dynamic conception of the classifications of critical thinking. The authors of the revised taxonomy underscore this dynamism, using verbs to label their categories and subcategories (rather than the nouns of the original taxonomy). These “action words” describe the cognitive processes by which thinkers encounter and work with knowledge:

Mindset Theory

The concept of Mindset Theory was developed by psychologist Carol Dweck (1946- ) and popularized in her book, Mindset: The New Psychology of Success (2016). In recent years, many schools and educators have started using Dweck’s theories to inform how they teach students.

A mindset, according to Dweck, is a self-perception or self-theory that people hold about themselves. Believing that you are either intelligent or unintelligent is a simple example of a mindset. People may also have a mindset related to their personal or professional lives— “I’m a good teacher” or “I’m a bad parent,” for example. People can be aware or unaware of their mindsets, according to Dweck, but they can have a profound effect on learning achievement, skill acquisition, personal relationships, professional success, and many other dimensions of life.

Dweck’s educational work centers on the distinction between a fixed mindset and growth mindset. According to Dweck, in a fixed mindset, people believe their basic qualities, like their intelligence or talent, are simply fixed traits. They spend their time documenting their intelligence or talent instead of developing them. They also believe that talent alone creates success—without effort. Dweck’s research suggests that students who have adopted a fixed mindset believe that they are either smart or dumb, and there is no way to change this. For example, they may learn less than they could or learn at a slower rate, while also shying away from challenges, since poor performance might either confirm they can’t learn if they believe they are dumb or indicate that they are less intelligent than they think if they believe they are smart. Dweck’s findings also suggest that when students with fixed mindsets fail at something, as they inevitably will, they tend to tell themselves they can’t or won’t be able to do it (“I just can’t learn Algebra”), or they make excuses to rationalize the failure (“I would have passed the test if I had had more time to study”).

Alternatively, in a growth mindset, people believe that their most basic abilities can be developed through dedication and hard work—brains and talent are just the starting point. This view creates a love of learning and a resilience that is essential for great accomplishment. Students who embrace growth mindsets—the belief that they can learn more or become smarter if they work hard and persevere—may learn more, learn it more quickly, and view challenges and failures as opportunities to improve their learning and skills.

Dweck’s delineation of fixed and growth mindsets has potentially far-reaching implications for schools and teachers since the ways in which students think about learning, intelligence, and their own abilities can have a significant effect on learning progress and academic improvement. If teachers encourage students to believe that they can learn more and become smarter if they work hard and practice, Dweck’s findings suggest, it is more likely that students will, in fact, learn more, and learn it faster and more thoroughly than if they believe that learning is not determined by how intelligent or unintelligent they are. Her work has also shown that a growth mindset can be intentionally taught to students. Teachers might, for example, intentionally praise student effort and perseverance instead of ascribing learning achievements to innate qualities or talents (for example, giving feedback such as “You must have worked very hard” rather than “You are so smart.”

Read more about mindset in Christine Gross-Loh’s interview with Dweck for the Atlantic, titled Don’t Let Praise Become the Consolation Prize. In the interview, Dweck clarifies some common misconceptions which are often made. The interview can be found by following this link: https://www.theatlantic.com/education/archive/2016/12/how-praise-became-a-consolation-prize/510845/

Media Attributions

- Multiple Intelligences chart © Howard via Wikimedia Commons is licensed under a CC BY-SA (Attribution ShareAlike) license

- Bloom’s Taxonomy © Deirdre Budzyna via. ROTEL is licensed under a CC BY-NC-SA (Attribution NonCommercial ShareAlike) license

self-perception or self-theory

a mindset in which people believe their basic qualities, like their intelligence or talent, are simply fixed traits

a mindset in which people believe that their most basic abilities can be developed through dedication and hard work