Chapter Three: Domains in Development

Physical/Biological Development

Of all the domains of development, physical development is the most obvious and possibly easiest to measure with modern medical techniques. Some aspects of physical development are universal, biological processes that all children experience, but there is a great deal of variation. For example, most children get taller and stronger as they grow, but the range of what is “normal” is vast, and can be influenced by a range of factors including nutrition, genetics, and experience. Here we will look at physical development such as changes in children’s height and weight, the development of gross and fine motor skills, and losing teeth.

Height and Weight

Typically, children grow physically larger in two ways: they get taller and they get heavier. It is considered normal, healthy development if these two things increase in ratio to one another; as height increases, so should weight. Often, we think of weight as being how much fat we are carrying around, but most of the human body is made up of other things which weigh a lot!

As children grow, their height and weight are increasing because their bones are increasing in both size and density. On top of those bones are muscles, which are connected by ligaments and tendons. Internal organs, such as the lungs and heart, are also growing as they have more space to fill inside the ribcage. Throughout the body there are veins, arteries, and capillaries; all of these help to move fluid around for transporting nutrients and gases.

If you have ever sat in the doctor’s waiting room, perhaps you have noticed a chart on the wall that indicates a “normal” weight range according to your height and age. Although these charts become less helpful in adulthood, for infants and young children they can be a quick way to determine if a child is physically developing along a normal trajectory.

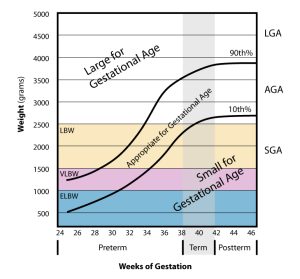

The chart below is one example that shows the normal distribution for the weight of a fetus during gestation up to 46 weeks.

If you pay attention to the percentages on the far right side, you might notice that “normal” is a big range – 80% variance! This is because physical development – like most forms of development – can be widely varied across individuals yet still within a range that is considered healthy. Even at the 10th percentile, weight is considered appropriate; it is not unless the fetus weighs less than 2500 grams at term that the baby is considered low birth-weight (LBW).

If you pay attention to the percentages on the far right side, you might notice that “normal” is a big range – 80% variance! This is because physical development – like most forms of development – can be widely varied across individuals yet still within a range that is considered healthy. Even at the 10th percentile, weight is considered appropriate; it is not unless the fetus weighs less than 2500 grams at term that the baby is considered low birth-weight (LBW).

This image also indicates when and how much growth should increase over the span of gestation. As you can see from the two dark lines, a normally developing fetus should steadily gain weight for the duration of gestation, and then that growth should taper off around week 42.

Throughout the chapters of this book, you will encounter additional charts and diagrams similar to this one which indicate the typical pattern of growth for children from infancy through age 8. As you read through each chapter, keep these things in mind about the development of height and weight across childhood:

- There is a wide range of variance within what is considered “normal” development. Children come in all sizes, and grow at different rates depending on a range of biological and environmental factors.

- Not every scale is going to be the same in a depiction of growth, so pay careful attention to the numbers on the outside of the graph, which will help you to understand what is being measured. Some charts, such as this one, are considering weight compared to week of gestation. After birth, these variables may change to include length (for infants), height, weight, age (in days, weeks, months, or years), or possibly Body Mass Index (BMI).

Gross and Fine Motor Skills

Gross motor movements are those associated with the large muscles of the body: arms, legs, torso, etc. while fine motor skills are those completed with the smaller muscles such as those in your hands and fingers.

As you will read in an upcoming chapter, control of your body depends on a good connection throughout your central nervous system (CNS). At birth, infants’ are still developing, and there is not yet a strong signal between the brain and the muscles. Additionally, in the compact environment of the womb, the fetus did not have much opportunity to stretch or strengthen muscles. For the first few months of life, the infant will be developing the brain-body coordination and basic muscle control necessary for both gross and fine motor skills. Once that foundation is set, however, physical development moves forward rapidly! At birth, infants cannot move on their own and yet by age 8 a child is able to walk, run, jump, and skip which takes an enormous amount of muscular strength and control!

Fine motor skills take more time to develop than gross motor skills, because the smaller muscles of the body are generally more difficult to learn to control. While it is relatively easy to learn how to control a whole limb in space, it can be challenging to figure out how to work the tiny digits at the end of your arm! Have you ever tried to manipulate something very small, and found that it was hard to get your fingers to cooperate? Tiny movements, such as picking up a Cheerio in a pincer grip, or controlling the movement of your tongue in the back of your mouth to distinguish between /ch/ and /ch/ requires an enormous amount of control. This only comes with practice, which allows both the brain and the muscles to become familiar with the movement.

Throughout the chapters of this book which detail each stage of early childhood (infancy, toddlerhood, preschool age, and school age), you will read in more detail about the specific milestones for physical development associated with each age.

Universals in Physical Development

Although there are always exceptions to every rule when it comes to human development, most of us are born without teeth, and then throughout our childhood we grow and lose one set before our adult teeth come in. Teeth are not the only universal physical development, but they might be the weirdest! Have you ever wondered where those teeth come from, and why we lose our baby teeth?

As it turns out, we are born with all of our teeth; they are simply embedded in our skull until it is time for them to emerge! Most babies are born without any teeth (although neonatal and natal teeth are a thing!). The most common explanation for this is simply that in general human babies are born very early compared to every other mammal species; they are simply too young to have their teeth erupt yet. Human infants are born at a point at which they are most likely to survive, but are not yet so large that they will get stuck in the birth canal. To make that happen, the head can only be so large, and that includes the bones of the jaw.

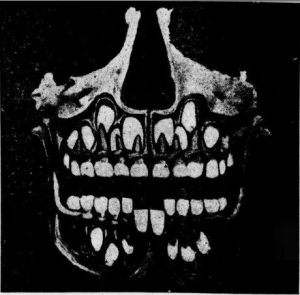

In utero, the teeth themselves have formed, along with the bones of the skull. Check out the exceptionally creepy picture to the right – that is what a child’s skull looks like under an x-ray! In this picture, the first set of teeth have already erupted, but the “adult teeth” are still embedded in the upper and lower jaw bones.

After birth, it takes approximately 6 months before the first set of “baby teeth” will start to come through the gums. In the meantime, most infants are able to “chew” soft foods without issue. Teeth are not essential for eating but do increase the range of foods that an infant can manage. Children keep this first set of teeth for somewhere between 5-7 years, depending on their rate of growth, and their overall health. These teeth are smaller simply because they must fit within the small jawbone of the baby. As a child’s skeletal structure grows, it creates more space for the teeth and actually widens the opening where new teeth can come in. Teeth start to feel loose when the socket they sit in starts to widen; when it becomes too large, the baby tooth will fall out and the adult tooth can move in.

Remember, although we have discussed this as a universal piece of development, there are going to be exceptions. Some children do not develop teeth, or their teeth are problematic for some reason. Like everything, the environment can affect dental development. Anything that can influence how the skeleton develops can also impact the teeth. Additionally, oral hygiene in toddlers and young children can impact dental and cardiovascular health throughout life.

Media Attributions

- Weight vs Gestational Age © Yehudamalul, via. Wikimedia Commons is licensed under a CC BY-SA (Attribution ShareAlike) license

- X-ray with juvenile and permanent teeth © Wikimedia Commons is licensed under a Public Domain license