Chapter Two: Theorists and Theories of Development

Psychosocial Theory

Erik H. Erikson (1902-1994), was a German-born, world-renowned scholar of the behavioral sciences. Erikson is one of the few theorists of his time to address development through the entire lifespan, not just childhood. As our society as a whole is becoming increasingly older, and thus there is an increasing need to understand individuals as they advance into old age, Erikson’s views are even more valuable and relevant today than when he first proposed them. Erikson is, perhaps, best known for his theory of psychosocial development. Having studied psychoanalysis (the prevailing theory of personality development at the time) Erikson began to shift from Freud’s emphasis on psychosexual crises to one of psychosocial conflicts. Drawing upon Sigmund Freud’s basic psychosexual theories, Anna Freud’s explorations in the psychological development of children, and his own experience as an educator, he developed a theory which outlined eight distinct stages of development over the lifespan.

According to Erikson’s theory, each of the eight stages of his psychosocial theory is characterized by a different psychosocial crisis of two conflicting forces. Because each stage builds upon the successful completion of earlier stages, any unresolved challenges of a particular stage will most likely resurface as problems later in an individual’s development. In this way, the outcomes of each stage are not permanent and can be modified by later experiences as challenges are re-confronted. Although his stages seem to align with periods of development, they are not necessarily perfectly sequential; it is possible to move from one stage up to another, and then at some point, move back down to a previous stage. For example, imagine a scenario in which you are an adult in the generativity vs. stagnation stage, having successfully resolved all the previous stages, when you find out that your spouse has cheated on you, and you decide to get a divorce. In this case, it would be perfectly expected that you would again be struggling with issues of trust, intimacy, and possibly even identity. Your success or failure at resolving these struggles previously will, in part, determine your resilience during this challenge.

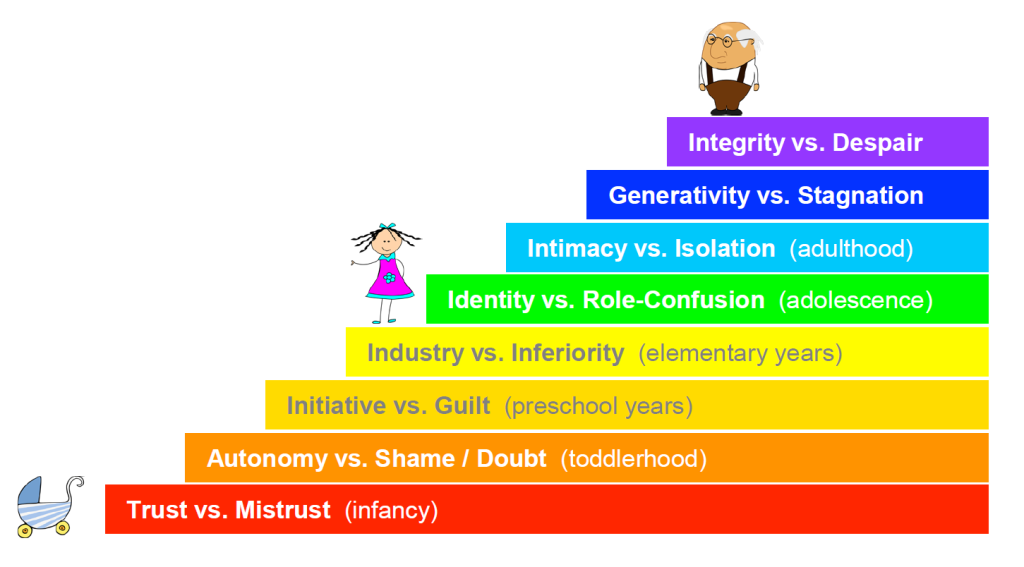

Beginning in infancy, his eight stages (from bottom to top) are:

Trust vs. Mistrust (Infancy)

The first stage of Erik Erikson’s theory centers around an infant’s basic needs being met by its caregivers, and this interaction leads to trust or mistrust. Trust, as defined by Erikson, is an essential belief in the reliability of others, as well as a fundamental sense of one’s own trustworthiness. The infant depends on its caregivers, typically its mother, for sustenance and comfort. At this stage, the child’s relative understanding of the world and society comes directly from its caregivers and their interaction with the child. A child’s first trust is always with its caregiver, whoever that might be. If caregivers expose an infant to warmth, regularity, and dependable affection, the infant’s view of the world will be one of trust. Should caregivers fail to provide a secure environment or to meet the child’s basic needs, a sense of mistrust will result (Bee & Boyd, 2009). Development of mistrust can lead to feelings of frustration, suspicion, withdrawal, and a lack of confidence throughout childhood, as well as later in life.

According to Erik Erikson, the major developmental task in infancy is to learn whether or not other people, especially primary caregivers, regularly satisfy basic needs. If caregivers are consistent sources of food, comfort, and affection, an infant learns trust (i.e., others are dependable and reliable). If they are neglectful, or perhaps even abusive, the infant instead learns mistrust (i.e., the world is an undependable, unpredictable, and possibly a dangerous place). The child’s number one need in this stage is to feel safe, comforted, and well cared for (Bee & Boyd, 2009).

Autonomy vs. Shame/Doubt (Toddlerhood)

As children gain increasing control over their motor abilities, they begin to move around and explore their surroundings. Trusting caregivers provide a strong, secure base from which children can venture out to assert their will and newfound independence. Caregivers’ patience and encouragement help to foster a sense of autonomy—or independence. Highly restrictive caregivers, caregivers who demand too much self-regulation too soon, caregivers who refuse to let children perform tasks of which they are capable, or discourage early attempts at self-sufficiency, instill in children a sense of shame and doubt in their ability to handle new challenges. As a result, children learn to withdraw from their world.

Initiative vs. Guilt (Preschool Years)

The development of courage and independence are what set preschoolers, ages three to six years of age, apart from other age groups. Young children in this category face the challenge of initiative versus guilt. As described by Bee and Boyd (2009), the child during this stage faces the complexities of planning and developing a sense of judgment. Because this sense of planning and judgment is still developing, along with initiative, sometimes negative behaviors (such as throwing objects, hitting, or yelling) can also emerge. These behaviors are often the result of the child’s frustration in not being able to achieve a goal as planned. Sometimes preschoolers take on projects they can readily accomplish, but at other times they undertake projects that are beyond their capabilities or that interfere with other people’s plans and activities. If caregivers and preschool teachers encourage and support children’s efforts, while also helping them make realistic and appropriate choices, children develop a healthy sense of initiative in planning and undertaking activities. If, instead, adults discourage the pursuit of independent activities or dismiss them as silly and bothersome, children develop guilt about their needs and desires.

Industry vs. Inferiority (Elementary Years)

The failure to master trust, autonomy, and initiative may cause the child to doubt themselves, leading to feelings of shame, guilt, defeat, and/or inferiority. Children at this age are becoming more aware of themselves as individuals; they work hard at being responsible, being good, and “doing it right.” At this stage, children are very eager to learn and accomplish progressively complex skills, such as reading, writing, telling time, etc. Erikson viewed the elementary school years as particularly critical for the development of self-confidence. Ideally, elementary school provides many opportunities to achieve the recognition of teachers, caregivers, and peers by producing things—drawing pictures, solving addition problems, writing sentences, and so on. If children are encouraged to make and do things and are then praised for their accomplishments, they begin to demonstrate industry by being diligent, persevering at tasks until completed, and putting work before pleasure. If children are, instead, ridiculed or punished for their efforts or if they find they are incapable of meeting their teachers’ and caregivers’ expectations, they develop feelings of inferiority about their capabilities (Crain, 2011).

Identity vs. Role-Confusion (Adolescence)

As adolescents become newly concerned with how they appear to others, the need to settle on an identity becomes an increasing priority. As they make the transition from childhood to adulthood, adolescents ponder the roles they will play in the adult world. Initially, they are apt to experience some role-confusion—mixed ideas and feelings about the specific ways in which they will fit into society, and they may experiment with a variety of behaviors, social groups, and activities. Erikson is credited with coining the term identity crisis to explain the negotiation of this particular challenge. Eventually, Erikson proposed, most adolescents achieve a sense of identity regarding who they are and where their lives are headed. The teenager must achieve a sense of identity in career, gender roles, politics, and religion, among others. This stage is considered to be a turning point in human development because it marks the transition from childhood to adulthood, and more specifically, seems to be the reconciliation between the person one has come to be and the person society expects one to become. In relation to the eight life stages as a whole, the fifth stage corresponds to a crossroads.

Intimacy vs. Isolation (Early Adulthood)

At the start of this stage, identity vs. role confusion is coming to an end though it still lingers at the foundation of this stage (Erikson, 1950). Young adults are still eager to blend their identities with friends; they want to fit in. Once people have established their identities, they are ready to make long-term commitments to others. They become capable of forming intimate, reciprocal relationships (for example, through close friendships or marriage) and willingly make the sacrifices and compromises that such relationships require. If people cannot form these relationships of intimacy (perhaps because of their own needs), a sense of isolation may result, provoking feelings of darkness and angst.

Generativity vs. Stagnation (Middle Adulthood)

The stage of generativity has broad applications for family relationships, work, and society. “Generativity, then, is primarily the concern in establishing and guiding the next generation. . . the concept is meant to include. . . productivity and creativity” (Erikson, 1950, p. 240). In other words, during middle adulthood, the primary developmental task is one of contributing to society and helping to guide future generations. Socially-valued work and disciplines are expressions of generativity. As a person experiences successes during this stage, perhaps by raising a family or working toward the betterment of society, a sense of generativity—of productivity and accomplishment—results. In contrast, a person who is self-centered and unable or unwilling to help society move forward develops a feeling of stagnation or dissatisfaction with his or her relative lack of productivity Berk, 2017).

Integrity vs. Despair (Older Adulthood)

As we grow older and become senior citizens, we tend to slow down our productivity and explore life as retired people. It is during this time that we contemplate our accomplishments and are able to develop integrity if we see ourselves as leading a successful life. If we see our life as unproductive or feel that we did not accomplish our life goals, we become dissatisfied with life and develop a sense of despair, often leading to depression and hopelessness. This stage may manifest itself out of sequence when individuals feel they are near the end of their lives (such as when receiving a terminal disease diagnosis) (Santrock, 2013).

Criticism of Psychosocial Theory

Erikson’s theory may be questioned as to whether his stages must be regarded as sequential and only occurring within the age ranges he suggests. There is debate as to whether people only search for identity during the adolescent years or if one stage needs to happen before other stages can be completed. Erikson himself states that each of these processes occurs throughout the lifetime in one form or another, and he emphasizes these periods only because it is at these times that the conflicts become most prominent (Erikson, 1956).

Educational Implications

Teachers who apply psychosocial development in the classroom create an environment where each child feels appreciated and is comfortable with learning new things and building relationships with peers.

At the preschool level, teachers want to focus on helping children develop healthy personalities and

- Find out what students are interested in and create projects that incorporate their area of interest.

- Make sure to point out and praise students for good choices.

- Offer continuous, authentic feedback.

- Not ridicule or criticize students. They should find a private place to talk with a child about a poor choice or behavior.

- Help students formulate their own alternate choices by guiding them to a more positive solution and outcome.

- When children experiment, they should not be punished for trying something that may turn out differently from what the teacher had planned.

At the elementary level, teachers should focus on achievement and peer relationships and

- Create a list of classroom duties that need to be completed on a scheduled basis. Ask students for their input when creating the list, as well as giving them a say in who will be in charge of what.

- Discuss and post classroom rules.

- Make sure to include students in the decision-making process when discussing rules.

- Encourage students to think outside of their day-to-day routine by role-playing different situations.

- Let students know that striving for perfection is not as important as learning from mistakes.

- Teach children resilience.

- Encourage children to help students who may be having trouble socially and/or academically.

- Never allow any child to make fun of or bully another child.

- Build confidence by recognizing success in what children do best.

- Provide a variety of choices when making an assignment so that students can express themselves with a focus on their strengths.

Media Attributions

- Psychosocial theory © Deirdre Budzyna via. ROTEL is licensed under a CC BY-SA (Attribution ShareAlike) license

- Old Man © Pixabay is licensed under a CC0 (Creative Commons Zero) license

describes growth and change throughout life, focusing on social interaction and conflicts that arise during different stages of development

as defined by Erikson, is an essential belief in the reliability of others, as well as a fundamental sense of one's own trustworthiness

When caregivers fail to provide a secure environment or to meet the child’s basic needs

independence; self-regulation

close familiarity or friendship

a sense of productivity and accomplishment

a sense of dissatisfaction due to a perceived of lack of productivity; a sense of being still rather than moving forward

the state of being whole and complete

loss of hope