Chapter Eight: Early Childhood Development

Social and Emotional Development in Preschool

Learning Objectives

- What characterizes young children’s socioemotional development?

- What roles do families play in young children’s development?

- How are peer relations, play and television involved in young children’s development?

Emotional Development

Emotions are strong feelings deriving from one’s circumstances, mood, or relationships with others. Self-conscious (evaluative) emotions first appear at about 2½ years. Pride is felt when a successful outcome results in joy. Guilt results from judging efforts as failure. Emotional development is heavily influenced by parents’ responses.

Young Children’s Understanding of Emotions: From ages 4 to 5 children show increased ability to reflect on emotions. Self-regulation of emotions continues. Parents play an important role in its development through emotional coaching by nurturing and using praise. Emotional dismissal is when a parent ignores and denies. Emotions also play a big role in peer relations. Moody, negative children experience greater peer rejection. Emotionally positive children are popular. Children controlling emotional responses are more likely to show social competence (Gordon & Browne, 2017; Hyson, 2014).

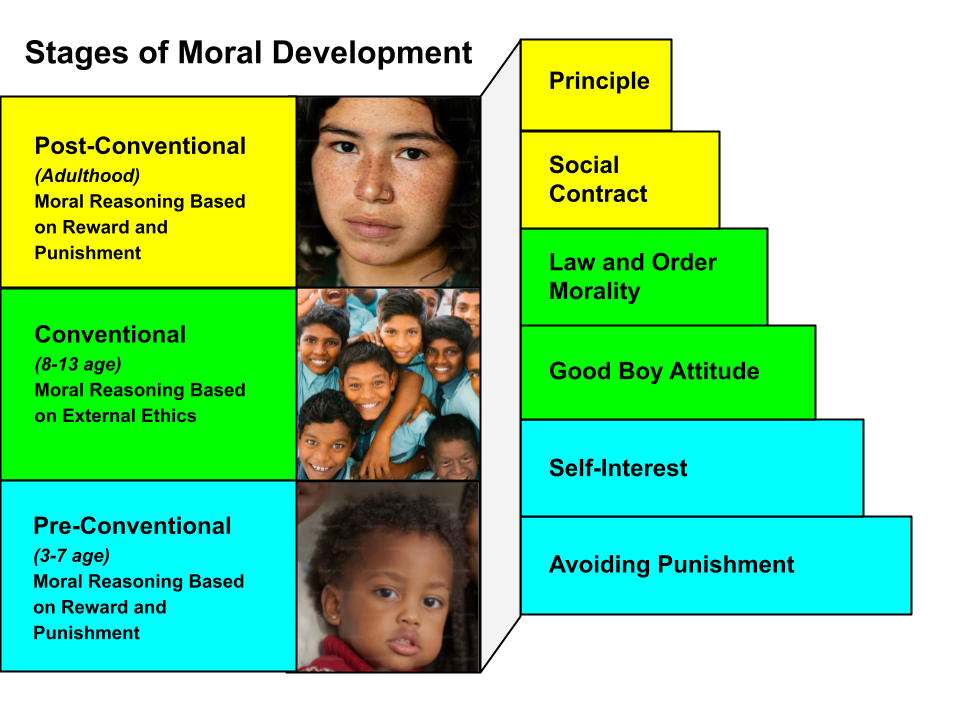

Moral Development

Moral Development refers to rules and regulations about what people should do in interactions with other people. Piaget extensively researched children. He wrote about two distinct stages of how children think about morality.

Here is a chart outlining Piaget’s Theory of Moral Development, heteronomous morality and autonomous morality.

Imminent justice is the belief that if a rule is broken, punishment will be meted out immediately. This is characteristic of heteronomous morality. Autonomous morality realizes that punishment is not inevitable.

Gender

Gender is the social and psychological dimension of being male or female. A gender role is a set of expectations of how females or males should think, act, and feel. Gender typing is a process for acquiring thoughts, feelings and behaviors considered appropriate for one’s gender in their culture. There are many things that impact children’s beliefs about gender.

Peer Influence

Gender plays an important role in interaction with peers. Children prefer same-sex groups by age 3, and this preference increases through age 12. Gender also impacts social situations. Boys in preschool engage in rough and tumble play and are very competitive. Girls engage in collaborative discourse. More time in same-sex groups is linked to more gender-stereotyped behavior (Berk, 2017).

Teacher Influence

Teachers also have a strong influence on beliefs about gender. Boys’ academic problems tend to be ignored more frequently. They experience more learning problems, receive more criticism, and are more likely to be stereotyped as having a behavior problem. Teachers often spend more time disciplining boys and more time giving girls academic tasks to complete.

School and Media Influences

On television, females are often portrayed as less competent. Most prime-time characters are male and traditional roles are reinforced. Most advertising continues to reflect traditional roles.

Gender Schema organizes the world in terms of female and male. Children gradually develop schemas of what is gender-appropriate and gender-inappropriate in their culture.

Socialization is also influenced by parenting styles, sibling relationships and the context of the family structure.

There are four different parenting styles:

- Authoritative: clear expectations, firm consequences

- Authoritarian: harsh, strict punishment, child does not have a voice

- Neglectful: uninvolved, disinterested

- Indulgent: no limits, caregiver gives child everything they ask for (Jensen & Arnett, 2019).

Child Abuse

Punishment sometimes leads to abuse. Types of maltreatment, which include physical maltreatment, child neglect, and sexual and emotional abuse, are all causes for concern. Here are some warning signs to be aware of: questionable patterns of injuries, age-inappropriate sexual knowledge, poor hygiene, food hoarding, and stealing and behavioral extremes.

Developmental consequences of abuse: Poor emotional regulation, attachment and peer relation problems, school difficulties, psychological problems and a later risk of violence and substance abuse. As a teacher, you are a mandated reporter and legally you must report any suspicion of abuse.

Sibling relationships and birth order: Sibling relationships can be both pleasant and aggressive. Siblings treat children differently than parents do. Extensive sibling conflict can be linked to poor outcomes. Birth order can affect sibling relationships.

Importance of Play

Play is a pleasurable activity engaged in for its own sake. It can increase health, release tensions and help children control conflicts. Play also helps with cognitive development. Therapists often use play therapy to help children work through problems.

Social Development in Preschool: Friendship

In infancy and toddlerhood, social interactions with peers are often limited to proximity and to parents’ choice. However, upon entering preschool, children suddenly have the chance to play with new peers, in new settings. Unlike early playdates, which are closely monitored and in which parents may choose to intervene to redirect play and to initiate cooperative play, in preschool, children are more likely to be encouraged to play with one another without a great deal of adult guidance, for the purpose of creating social skills.

In a new setting, with new peers, there is often a pattern to the development of social interactions.

Preschool children will not always follow these exact phases, but they are most common and early childhood educators can use this pattern to help set up their classroom for new students, to help move them through the stages.

Nonsocial Play: It may seem counterintuitive, but the first type of play that many preschool students engage in is “nonsocial”, which just means that children play at the same time and perhaps even in the same area, but their play is self-centered. Even in a group of 4-5 children, you may see each child playing with an individual toy, talking to themselves and not one another, and following an internal plan for the play that is not shared with or dependent on what any of the other children are doing.

Parallel Play: As preschoolers become more accustomed to the group setting of the classroom, their play begins to be more social as well. Parallel play describes activities that children participate in while physically near each other and often using the same toys, but the intention is still mostly internal, and the social aspect occurs only in an effort to share (or not share) space and objects. For example, two children may be playing in a block center with the same set of blocks, but each is building a separate structure that is not a shared project. This sort of play is an important first step in helping children understand how to share resources (toys and space) and to become aware of other children in their environment. This period of parallel play can be challenging for children who have limited experience with same-age peers because they may not be used to having to negotiate sharing toys with other children who also don’t know how to navigate this new social world!

Associative Play: As preschool children get better at parallel play, they will gradually start to incorporate one another into games and activities. This might start out as joining their two block towers or sharing crayons during an art project. The intention of the play may not yet be shared since each child likely has his or her own ideas about what the purpose of the game is; however, they are working together more overtly and are probably speaking to one another to figure out next steps (Gordon & Brown, 2017. This language is likely to be directive “Give me that.” as opposed to negotiating phrases such as “should we use that block?”)

Cooperative Play: Finally, as preschool children settle into the rhythm of group play and social interactions, they become more comfortable and able to talk to peers. They develop more cognitive awareness of their own intentions, and play becomes cooperative. At this stage, children are playing together intentionally, sharing objects and purpose for games and activities. They may be making up games with shared rules or planning projects together. Now the block building is a joint effort to make the tallest tower, with language being used to negotiate how that will be done. Games have rules, although those may be questioned and changed repeatedly as play goes on!

Television, Prosocial Behavior and Aggression: Watching too much television can cause aggression. Children who watch less television are more likely to engage in prosocial behavior, develop higher level cognitive skills and experience greater achievement (Gordon & Brown, 2017; Shaffer, 2000).

Media Attributions

- Stages of Moral Development © Doris Buckley via. the ROTEL Project is licensed under a CC BY-NC-SA (Attribution NonCommercial ShareAlike) license