Part 2: “Good Trouble, Necessary Trouble”

Learning Objectives

By the end of this section, you will be able to:

- identify former United States Representative and civil rights activist John Lewis.

- articulate the concept of “good, necessary trouble.”

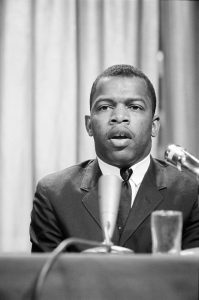

Who Was John Lewis?

John Lewis was both a witness to history and a maker of history. He was born on February 21, 1940, in Alabama, into a family of sharecroppers. Lewis first met Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr., when he was eighteen. While in college at the American Baptist Theological Seminary in Nashville, Tennessee, he became involved in the Nashville Student Movement, thus beginning his work in civil rights activism. As an activist, he was involved in the desegregation of lunch counters, in the Freedom Riders, in the Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee (serving as chairman), in “Bloody Sunday” in Selma, in the Voter Education Project, and in the March on Washington in 1963. In the latter, he was considered one of the “bix six” leaders along with Dr. King. Indeed, he spoke directly before King gave his famous “I Have a Dream” speech – his own speech having been “toned down” by the other organizers.

During his civil rights activities, despite his commitment to the philosophy of nonviolence that he kept throughout his life, Lewis was imprisoned frequently and was injured often. He was the first Freedom Rider to be attacked, and his skull was fractured in Selma during “Bloody Sunday” on March 7, 1965.

Lewis was first elected to the House of Representatives, as representative of Georgia, in 1986, after which he was reelected 18 times. During his time in Congress, Lewis continued to be an activist, introducing and supporting legislation affecting marginalized groups and attending protests for causes in which he believed. Lewis understood that culture and history were important. For fifteen years, he introduced a bill every year to create a national African American museum in Washington, which eventually led to the opening of the Smithsonian National Museum of African American History and Culture in 2016. Lewis was also the first Congressperson to write a graphic novel, a trilogy titled March.

John Lewis died on July 17, 2020, from pancreatic cancer. He was the last living member of the “bix six.”

See John Lewis’ autobiography Walking with the Wind: A Memoir of the Movement for the detailed story of his life.

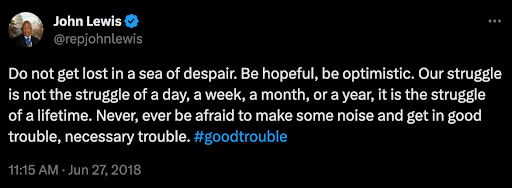

What Is “Good, Necessary Trouble”?

On March 1, 2020, John Lewis stood on the Edmund Pettus Bridge in Selma, Alabama, to commemorate “Bloody Sunday,” where, sixty-five years earlier, he had been severely beaten by law enforcement for crossing the bridge with 600 others in peaceful protest against police brutality after the killing of twenty-six-year-old Jimmie Lee Jackson. During his speech on that occasion, he encouraged those listening to “get in good trouble, necessary trouble.” In his book Across That Bridge: A Vision for Change and the Future of America that he originally wrote in 2012 and then added an introduction to in 2017, Lewis explores more of what he means by those words:

“Ordinary people with extraordinary vision can redeem the soul of America by getting in what I call good trouble, necessary trouble. Voting and participating in the democratic process are key. The vote is the most powerful nonviolent change agent you have in a democratic society […] You must also study and learn the lessons of history because humanity has been in this soul-wrenching, existential struggle for a very long time.”

“Trouble,” in Lewis’ definition, is not a synonym for reckless, purposeless, or chaotic behavior. His “trouble,” inspired by the actions of those like Rosa Parks, is action and affecting change, and “good, necessary trouble” is the attempt, the struggle, to contribute to positive change. Thus, voting and education, especially when there are barriers that must be overcome to achieve either, are aspects of “good, necessary trouble.”

Affecting positive change often requires struggle. Lewis grew up in a time when he, as a Black man, was not allowed to vote nor was he allowed to have a library card. He became a leader of the Civil Rights Movement that made voting and education rights, among other rights, possible, if not guaranteed, for all. But Lewis knew that no one movement would be enough to “offer all the growth humanity needs to experience,” and that growth requires labor, for “struggle is inevitable because tension motivates the imperative to change.” When he wrote the introduction to the reissue of Across That Bridge in 2017, he believed that the “sprouting of activist groups and angry sentiments represents a growing sense of discontent in America and around the world.” He writes:

“Let us appeal to our similarities, to the higher standards of integrity, decency, and the common good, rather than to our differences, be they age, gender, sexual preference, class, or color. If not, the people will put aside the business of their lives and turn their attention to the change they are determined to see, just as the Women’s March, Black Lives Matter, the Equal Justice Initiative, the Coalition of Immokalee Workers, and others so adamantly demonstrate.”

Lewis equated the protests, unrest, activism, and advocacy in the last decade or so to “good, necessary trouble” comparable to the Civil Rights Movement.

See John Lewis’ book Across that Bridge or watch the documentary John Lewis: Good Trouble for more on his philosophy.

Media Attributions

- John Lewis © Wikimedia is licensed under a Public Domain license

- John Lewis 2006 © Wikimedia is licensed under a Public Domain license

- @repjohnlewis © John Lewis via. X is licensed under a All Rights Reserved license