Chapter 19: Opera

Introduction

by Jennifer Bill

The 19th century witnessed a remarkable evolution in the world of opera, a period of artistic innovation and cultural transformation that would shape the course of this timeless art form. This era, marked by sweeping societal changes, technological advancements, and a fervent exploration of human emotions, saw opera undergo a profound metamorphosis, reflecting the dynamic spirit of the times.

As the echoes of the classical opera lingered, the 19th century unfolded as a canvas upon which composers and librettists would paint vivid tales of love, heroism, passion, and the human condition. Building upon the foundations laid by their predecessors, composers like Giuseppe Verdi, Richard Wagner, and Giacomo Puccini embarked on a quest to push the boundaries of musical expression and dramatic storytelling. Through their innovative use of orchestration, harmony, and vocal technique, they created operas that resonated with the fervor of the Romantic movement, inviting audiences to explore the depths of emotion and the complexities of the human psyche.

The 19th century also witnessed the rise of nationalistic sentiments, as composers sought to infuse their operas with distinctive cultural identities. This era saw the birth of grand opera, with its opulent staging, intricate plots, and monumental choruses, as well as the emergence of realism in opera, which brought everyday life and relatable characters to the forefront of the operatic stage.

Technological advancements, such as gas lighting and more elaborate stage machinery, facilitated the creation of increasingly spectacular productions, enabling operatic stories to be told with unprecedented visual and emotional impact. Opera houses became cultural hubs where society’s elite gathered to witness these grand spectacles, while also offering a space for ordinary citizens to partake in the enchanting world of music and drama.

Throughout the 19th century, opera’s ability to encapsulate the full spectrum of human experience—from the sublime to the mundane—remained unchallenged. As composers grappled with themes of love, destiny, tragedy, and triumph, they created works that continue to resonate with audiences to this day.

19th Century French Opera

Grand Opera

19th-century French grand opera emerged as a grandiose and opulent genre that captivated audiences with its lavish staging, intricate narratives, and sumptuous music. This distinctive operatic style, often associated with composers like Giacomo Meyerbeer and Hector Berlioz, epitomized the era’s penchant for spectacle and drama.

Characterized by its larger-than-life themes and ornate productions, French grand opera showcased historical or mythological subjects, frequently set in distant lands and eras. These epic narratives often explored themes of love, power, political intrigue, and the clash between personal desires and societal expectations. The genre’s librettos were carefully crafted to include grand set pieces, ballet sequences, and impressive chorus scenes, all designed to showcase the splendor of the opera house and engage the audience’s senses.

The music of 19th-century French grand opera was equally extravagant, featuring elaborate arias, duets, and ensembles that showcased the singers’ vocal prowess. The composers of this genre were skilled at creating lush orchestral textures, utilizing grand orchestration to evoke a range of emotions and enhance the dramatic impact of the story. These operas often featured extended ballet sequences, reflecting the importance of dance in French culture and adding an extra layer of visual and artistic spectacle.

One of the most renowned examples of 19th-century French grand opera is Meyerbeer’s Les Huguenots, which delves into the religious conflicts of 16th-century France. Berlioz’s Les Troyens, based on the story of the fall of Troy from Virgil’s Aeneid, is another notable work within the genre. These operas were not only artistic feats but also cultural touchstones, reflecting the societal values and aspirations of the time.

Meyerbeer: Les Huguenots

Berlioz: Les Troyens

“Je vais mourir… Adieu fière cité”

Opera Comique

19th-century French opéra comique represents a charming and distinct facet of the operatic world, marked by its blend of light-hearted storytelling, spoken dialogue, and melodic grace. Rooted in the tradition of 18th-century opéra comique, this genre evolved and thrived during the 19th century, capturing the essence of French culture and society.

Opéra comique often featured relatable, everyday characters and relished in the comedic and romantic aspects of human relationships. The genre’s librettos created an intimate and accessible form of entertainment. These operas explored themes of love, mistaken identities, societal class differences, and the humorous trials and tribulations of everyday life.

While opéra comique maintained its lighthearted spirit, it also delved into deeper emotions and social commentary, reflecting the evolving tastes of the time. Composers like Adolphe Adam, Daniel-François-Esprit Auber, and Jacques Offenbach crafted melodies that were both catchy and emotionally resonant, further enhancing the genre’s appeal.

Offenbach: Orphée aux enfers

19th Century German Opera

German Romantic Opera

19th-century German romantic opera emerged as a profound and transformative artistic movement, deeply intertwined with the ideals of the Romantic era. Led by visionary composers like Carl Maria von Weber and Richard Wagner, this genre embraced a fusion of music, drama, and philosophy to create immersive and emotionally charged theatrical experiences.

At the heart of 19th-century German romantic opera was a departure from traditional operatic norms. Composers sought to create a seamless integration between music and drama, often composing their own librettos to ensure a harmonious union between text and melody. The operas featured intricate character development, complex psychological portrayals, and narratives that explored themes of fate, love, myth, and the sublime.

One of the defining features of German romantic opera was its use of leitmotifs, recurring musical themes associated with specific characters, emotions, or concepts. This technique, popularized by Wagner, added depth and layers of meaning to the music, allowing for a more nuanced and immersive storytelling experience.

Wagner’s monumental four-opera cycle, Der Ring des Nibelungen, exemplifies the grandeur and innovation of German romantic opera. Through its epic narrative inspired by Norse mythology, intricate character interactions, and profound philosophical themes, the cycle redefined the boundaries of operatic expression.

Weber’s Der Freischütz and Wagner’s Tristan und Isolde are also notable examples of this genre. Der Freischütz masterfully blends folkloric elements with supernatural intrigue, while Tristan und Isolde delves into the depths of human passion and transcendent love. Other examples include Marschner’s Der Vampyr and Hans Heiling along with Lortzing’s Undine.

Weber: Der Freischütz

19th Century Italian Opera

Opera seria

19th-century Italian opera seria represents a continuation and evolution of the earlier operatic tradition that emerged in the 18th century. Rooted in the bel canto style, this genre retained its focus on virtuosic singing and showcased the technical prowess of its singers, while also incorporating elements of romanticism and heightened emotion. Bel Canto is a style of operatic singing where florid melodic lines are delivered by voices of great agility and purity of tone.

Italian opera seria of the 19th century often featured historical or mythological subjects, drawing inspiration from classical literature and ancient tales. While the emphasis on vocal display remained prominent, composers like Vincenzo Bellini, Gaetano Donizetti, and Gioachino Rossini added deeper emotional layers to their works, creating characters that expressed a broader range of feelings and vulnerabilities.

The librettos of 19th-century Italian opera seria continued to revolve around themes of love, honor, and destiny, but they also delved into the complexities of human relationships and the inner struggles of the characters. The arias and ensembles were designed to highlight the singers’ ability to convey both technical brilliance and emotional depth.

Operas like Bellini’s Norma, Donizetti’s Lucia di Lammermoor, and Rossini’s Semiramide exemplify the 19th-century Italian opera seria style. These works combine exquisite vocal writing with rich orchestration, creating a synthesis of lyrical beauty and dramatic intensity.

While the genre retained its affinity for vocal ornamentation and expressive melodies, it adapted to the changing artistic currents of the 19th century. The legacy of 19th-century Italian opera seria lies in its ability to bridge the gap between the traditions of the past and the evolving tastes of the present, captivating audiences with its captivating vocal artistry and emotional resonance.

Donizetti: Lucia di Lammermoor

Bellini: Norma

Verdi: La Traviata

Opera buffa

Italian opera buffa of the 19th century preserved the essence of comedy and satire while embracing the changing cultural landscape. Through its wit, lively music, and relatable characters, it provided audiences with an opportunity to laugh, reflect, and connect with the delightful absurdities of human existence. This genre, characterized by its humorous and satirical plots, witty dialogue, and catchy melodies, remained a beloved form of entertainment that offered social commentary and comedic relief to audiences.

Italian opera buffa of the 19th century often featured relatable characters from everyday life, portraying the antics, misunderstandings, and romantic escapades of ordinary people. The librettos combined spoken dialogue with musical numbers, creating a dynamic interplay between spoken humor and melodic expression. This genre’s enduring appeal lay in its ability to entertain and amuse while subtly addressing societal norms and human weakness.

Composers such as Gioachino Rossini, Gaetano Donizetti, and Giuseppe Verdi excelled in crafting memorable and vivacious melodies that perfectly complemented the comedic spirit of the plots. These operas featured ensembles, duets, and arias that showcased the singers’ vocal dexterity and comedic timing, adding layers of amusement to the storytelling.

Notable examples of 19th-century Italian opera buffa include Rossini’s Il barbiere di Siviglia (The Barber of Seville), Donizetti’s L’elisir d’amore (The Elixir of Love), and Verdi’s Falstaff. These works exemplify the genre’s ability to weave humor, romance, and social commentary into engaging and enjoyable narratives.

Rossini: Barber of Seville

Verdi: Falstaff

Trends in German and Italian Opera

Adapted from “Romantic Opera” from Music 101 by Elliott Jones

Edited and additional material by Jennifer Bill

Bel canto, Verdi, and Verismo

The bel canto opera movement flourished in the early 19th century and is exemplified by the operas of Rossini, Bellini, Donizetti, Pacini, Mercadante, and many others. Literally “beautiful singing,” bel canto opera derives from the Italian stylistic singing school of the same name. Bel canto lines are typically florid and intricate, requiring supreme agility and pitch control. Examples of famous operas in the bel canto style include Rossini’s Il barbiere di Siviglia and La Cenerentola, as well as Donizetti’s Lucia di Lammermoor.

Following the bel canto era, a more direct, forceful style was rapidly popularized by Giuseppe Verdi, beginning with his biblical opera Nabucco. Verdi’s operas resonated with the growing spirit of Italian nationalism in the post-Napoleonic era, and he quickly became an icon of the patriotic movement (although his own politics were perhaps not quite so radical). In the early 1850s, Verdi produced his three most popular operas: Rigoletto, Il trovatore, and La traviata. But he continued to develop his style, composing perhaps the greatest French Grand Opera, Don Carlos, and ending his career with two Shakespeare-inspired works, Otello and Falstaff, which reveal how far Italian opera had grown in sophistication since the early 19th century.

Rigoletto

Otello

After Verdi, the sentimental “realistic” melodrama of verismo (operatic realism) appeared in Italy. This was a style introduced by Pietro Mascagni’s Cavalleria rusticana and Ruggero Leoncavallo’s Pagliacci that came virtually to dominate the world’s opera stages with such popular works as Giacomo Puccini’s La bohème, Tosca, Madama Butterfly, and Turandot.

La Boheme

Madame Butterfly

German-Language Operas

Italian opera held great sway over German-speaking countries until the late 18th century. It was not until the arrival of Mozart that German opera was able to match its Italian counterpart in musical sophistication. Mozart’s singspiel (comic opera) Die Entführung aus dem Serail (1782) and Die Zauberflöte (1791) were important breakthroughs in achieving international recognition for German opera.

The tradition was developed in the 19th century by Beethoven with his Fidelio, inspired by the climate of the French Revolution. Carl Maria von Weber (1786-1826) established German Romantic opera in opposition to the dominance of Italian bel canto. His Der Freischütz (1821) shows his genius for creating a supernatural atmosphere. Other opera composers of the time include Marschner, Schubert, and Lortzing, but the most significant figure was undoubtedly Wagner.

Richard Wagner (1813-1883) was one of the most revolutionary and controversial composers in musical history. Starting under the influence of Weber and Meyerbeer, he gradually evolved a new concept of opera as a Gesamtkunstwerk (a “complete work of art”), a fusion of music, poetry, and painting. He greatly increased the role and power of the orchestra, creating scores with a complex web of leitmotifs, recurring themes often associated with the characters and concepts of the drama, of which prototypes can be heard in his earlier operas such as Der fliegende Holländer, Tannhäuser, and Lohengrin; and he was prepared to violate accepted musical conventions, such as tonality, in his quest for greater expressivity. In his mature music dramas, Tristan und Isolde, Die Meistersinger von Nürnberg, Der Ring des Nibelungen, and Parsifal, he abolished the distinction between aria and recitative in favor of a seamless flow of “endless melody.” Wagner also brought a new philosophical dimension to opera in his works, which were usually based on stories from Germanic or Arthurian legends. Finally, Wagner built his own opera house at Bayreuth with part of the patronage from Ludwig II of Bavaria, exclusively dedicated to performing his own works in the style he wanted.

Bayreuth behind the scenes

Wagner: Ride of the Valkyries

Wagner: Tristan und Isolde

Opera would never be the same after Wagner and for many composers, his legacy proved a heavy burden. On the other hand, Richard Strauss (1864-1949) accepted Wagnerian ideas but took them in wholly new directions. He first won fame with the scandalous Salome and the dark tragedy Elektra, in which tonality was pushed to the limits. Then Strauss changed tack in his greatest success, Der Rosenkavalier, where Mozart and Viennese waltzes became as important an influence as Wagner. Strauss continued to produce a highly varied body of operatic works, often with libretti by the poet Hugo von Hofmannsthal.

Richard Strauss: Salome

During the late 19th century, the Austrian composer Johann Strauss II (1825-1899), an admirer of the French-language operettas composed by Jacques Offenbach, composed several German-language operettas (light opera), the most famous of which was Die Fledermaus, which is still regularly performed today. Nevertheless, rather than copying the style of Offenbach, the operettas of Strauss II had distinctly Viennese flavor to them, which cemented Strauss II’s place as one of the most renowned operetta composers of all time.

Johann Strauss II: Die Fledermaus

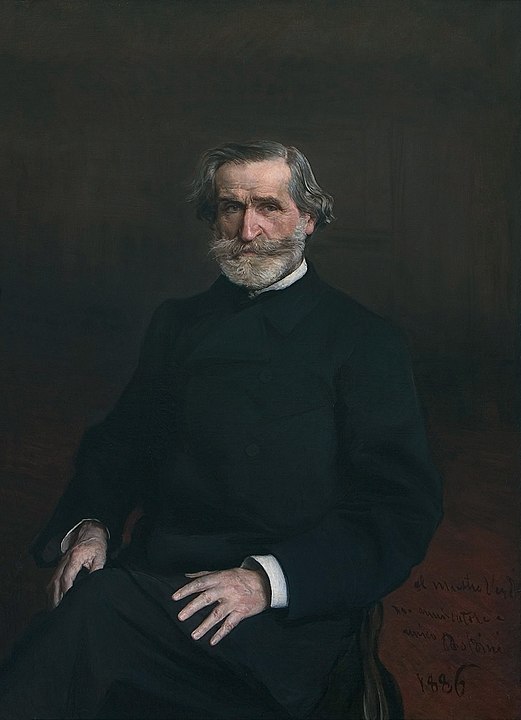

Giuseppe Verdi (1813-1901)

Giuseppe Fortunino Francesco Verdi was an Italian Romantic composer primarily known for his operas. He is considered, with Richard Wagner, the preeminent opera composer of the 19th century. Verdi dominated the Italian opera scene after the eras of Bellini, Donizetti, and Rossini. His works are frequently performed in opera houses throughout the world and, transcending the boundaries of the genre, some of his themes have long since taken root in popular culture, examples being “La donna è mobile” from Rigoletto, “Libiamo ne’ lieti calici” (The Drinking Song) from La traviata, “Va, pensiero” (The Chorus of the Hebrew Slaves) from Nabucco, the “Coro di zingari” (Anvil Chorus) from Il trovatore and the “Grand March” from Aida.

Verdi: ‘Anvil Chorus’

Focus Composition: Verdi, Excerpt from La Traviata (1853)

A good example of his operatic realism can be found in La Traviata, or The Fallen Woman (1853). This opera was based on a play by Alexandre Dumas. Verdi wanted it to be set in the present, but the censors at La Fenice, the opera house in Venice that would premiere the opera, insisted on setting it in the 1700s instead. Of issue was the heroine, Violetta—a companion prostitute for the elite aristocrats of Parisian society—with whom Alfredo, a young noble, falls in love. After wavering over giving up her independence, Violetta commits herself to Alfredo, and they live a blissful few months together before Alfredo’s father arrives and convinces Violetta that she is destroying their family and the marriage prospects of Alfredo’s younger sister. In response, Violetta leaves Alfredo without telling him why and goes back to her old life. Alfredo is angry and hurt and the two live unhappily apart. A consumptive, that is, one suffering from tuberculosis, Violetta declines and her health disintegrates. Alfredo’s father has a crisis of conscience and confesses to his son what he has done. Alfredo rushes to Paris to reunite with Violetta. The two sing a love duet, but it is soon clear that Violetta is very ill, and in fact, she dies in Alfredo’s arms, before they can go to the church to be married. In ending tragically, this opera ends like many other nineteenth-century tales.

Verdi wrote this opera mid-century with full knowledge of the Italian opera before him. Like his contemporary, Richard Wagner, Verdi wanted opera to be a strong bond of music and drama. He carefully observed how German opera composers such as Carl Maria von Weber and French Grand Opera composers such as Giacomo Meyerbeer had used much larger orchestras than previous opera composers, and Verdi himself also employed a comparably large ensemble for La Traviata. Verdi also believed in flexibly using the operatic forms he had inherited, and so although La Traviata does have arias and recitatives, the recitatives are more varied and lyrical than before and the alternation between the recitatives, arias, and other ensembles, are guided by the drama, instead of the drama having to fit within the structure of recitative-aria pairs.

A good example is “La follie…Sempre libera” from the end of Act I in which Violetta debates whether she is ready to give up her independence for Alfredo. Although at the end of the aria it seems that she has decided to remain free, Act II begins with the two lovers living happily together, and we know that the vocal injections sung by Alfredo as part of Violetta’s recitative and aria of Act I have prevailed. This piece is also a good example of how virtuosic opera had gotten by the end of the nineteenth century. Earlier Italian opera had been virtuosic in its use of ornamentation. Verdi, however, required a much wider range of his singers, and this wider range is showcased in the scene below. Violetta has a huge vocal range and performers must have great agility to sing the melismas in her part. As an audience, we are awed by her vocal prowess, a fitting response, given her character in the opera.

Listening Guide: “Follie” and “Sempre libera” from La Traviata

Performed by:

Diana Damrau as Violetta

Juan Diego Flórez as Alfredo

Yannick Nézet-Séguin conductor of the MET Opera Orchestra

- Composer: Verdi

- Composition: “Follie” and “Sempre libera” from La Traviata

- Date: 1853

- Genre: Recitatives and aria from an opera

- Form: Alternates between singing styles of accompanied recitative, with some repetition of sections.

- Text: Libretto by Francesco Maria Piave; Translation available at the following link: http://www.murashev.com/opera/La_traviata_libretto_English_Italian

- Performing Forces: Soprano (Violetta), tenor (Alfredo), and orchestra

What we want you to remember about this composition:

- The virtuoso nature of Violetta’s singing

- The subtle shifts between recitative and aria, now less pronounced than in earlier opera

- A large orchestra that stays in the background

Other things to listen for:

- Alfredo’s more lyrical melody in distinction to Violetta’s virtuosity

| Timing | Performing Forces, Melody, and Texture | Text |

| 0:00 | Violetta sings a very melismatic and wide-ranged melody with flexible rhythm; the orchestra provides sparse accompaniment | Accompanied recitative:

Follie! follie! Delirio vano è questo! Povera donna, sola, abbandonata in questo popoloso deserto che appellano Parigi. Che spero or più? Che far degg’io? Gioire, di voluttà ne’ vortici perir. |

| 0:44 | Violetta sings wide leaps, long melismas, and high pitches to emphasize these words | Accompanied recitative: Gioir! (Pleasure!) |

| 1:29 | Stronger orchestral accompaniment as Violetta sings a more tuneful melody in a lilting meter with a triple feel | Aria:

Sempre libera degg’io folleggiare di gioia in gioia, vo’ che scorra il viver mio pei sentieri del piacer. Nasca il giorno, o il giorno muoia, sempre lieta ne’ ritrovi, a diletti sempre nuovi dee volare il mio pensier. |

| 2:24 | Alfredo sings a more legato and lyrical melody in a high tenor range (this melody comes from earlier in the opera) | Alfredo’s melody:

Amore, amor è palpito . . . dell’universo intero – Misterioso, misterioso, altero, croce, croce e delizia, croce e delizia, delizia al cor. |

| 3:09 | Violetta sings her virtuoso recitative and then transitions into her aria style | Accompanied recitative and then aria:

Follie . . . Sempre libera |

| 4:32 | Alfredo sings his lyrical melody and Violetta responds after each phrase with a fast and virtuosic melisma | Alfredo and Violetta sing:

Repetition of text above |

Verdi’s Requiem

Although in this module we are focusing on opera, Verdi’s Requiem shows that our operatic composers wrote in other genres as well. The Romantic tendency toward grand gestures and the operatic composer’s tendency toward dramatic expression impacted other genres.

Moved by the death of compatriot Alessandro Manzoni, Verdi wrote Messa da Requiem in 1874 in Manzoni’s honor, a work now regarded as a masterpiece of the oratorio tradition and a testimony to his capacity outside the field of opera. Visionary and politically engaged, he remains—alongside Garibaldi and Cavour—an emblematic figure of the reunification process (the Risorgimento) of the Italian Peninsula.

Verdi: ‘Dies irae’ from Requiem

Richard Wagner (1813-1883)

Wilhelm Richard Wagner was a German composer, theatre director, polemicist, and conductor who is primarily known for his operas (or, as some of his later works were later known, “music dramas”). Unlike most opera composers, Wagner wrote both the libretto and the music for each of his stage works. Initially establishing his reputation as a composer of works in the romantic vein of Weber and Meyerbeer, Wagner revolutionized opera through his concept of the Gesamtkunstwerk (“total work of art”), by which he sought to synthesize the poetic, visual, musical, and dramatic arts, with music subsidiary to drama, and which was announced in a series of essays between 1849 and 1852. Wagner realized these ideas most fully in the first half of the four-opera cycle Der Ring des Nibelungen (The Ring of the Nibelung).

His compositions, particularly those of his later period, are notable for their complex textures, rich harmonies and orchestration, and the elaborate use of leitmotifs—musical phrases associated with individual characters, places, ideas, or plot elements. His advances in musical language, such as extreme chromaticism and quickly shifting tonal centers, greatly influenced the development of classical music. His Tristan und Isolde is sometimes described as marking the start of modern music.

Wagner had his own opera house built, the Bayreuth Festspielhaus, which embodied many novel design features. It was here that the Ring and Parsifal received their premieres and where his most important stage works continue to be performed in an annual festival run by his descendants. His thoughts on the relative contributions of music and drama in opera were to change again, and he reintroduced some traditional forms into his last few stage works, including Die Meistersinger von Nürnberg (The Mastersingers of Nuremberg).

Until his final years, Wagner’s life was characterized by political exile, turbulent love affairs, poverty, and repeated flight from his creditors. His controversial writings on music, drama, and politics have attracted extensive comment in recent decades.

Wagner’s later musical style introduced new ideas in harmony, melodic process (leitmotif), and operatic structure. Notably from Tristan und Isolde onwards, he explored the limits of the traditional tonal system, which gave keys and chords their identity, pointing the way to atonality in the 20th century. Some music historians date the beginning of modern classical music to the first notes of Tristan, which include the so-called “Tristan chord.”

The Tristan Chord

Focus Composition:

Conclusion to The Valkyrie (1876)

In the excerpt we’ll watch from the end of The Valkyrie, the second of the four music dramas in the Ring, Brünnhilde has gone against her father, and, because Wotan cannot bring himself to kill her, he puts her to sleep before encircling her with flames, a fiery ring that both imprisons and protects his daughter.

This excerpt provides several examples of the Leitmotivs for which Wagner is so famous. Their presence, often subtle, is designed to guide the audience through the drama. They include melodies, harmonies, and textures that represent Wotan’s spear, the god Loge—a shape-shifting life force that here takes the form of fire—sleep, the magic sword, and fate. The sounds of these motives are discussed briefly below.

The first motive heard in the video you will watch is Wotan’s Spear. The spear represents Wotan’s power. In this scene, Wotan is pointing it toward his daughter Brünnhilde, ready to conjure the ring of fire that will both imprison and protect her. Representing a symbol of power, the spear motive is played at a forte dynamic by the lower brass. Here it descends in a minor scale that reinforces the seriousness of Wotan’s actions.

Wotan commands Loge to appear and suddenly the music breaks out in a completely different style. Loge’s music—sometimes also referred to as the magic fire music—is in a major key and appears in upper woodwinds such as the flutes. Its notes move quickly with staccato articulations suggesting Loge’s free spirit and shifting shapes.

Depicting Brünnhilde’s descent into sleep, Wagner wrote a chromatic musical line that starts high and slowly moves downward. We call this phrase the Sleep motive.

After casting his spell, Wotan warns anyone who is listening that whoever would dare to trespass the ring of fire will have to face his spear. As the drama unfolds in the next opera of the tetralogy, one character will do just that: Siegfried, Wotan’s own grandson. He will release Brünnhilde using a magic sword. The melody to which Wotan sings his warning with its wide leaps and overall disjunct motion sounds a little bit like the motive representing Siegfried’s sword.

One final motive is prominent at the end of The Valkyrie, a motive which is referred to as Fate. It appears in the horns and features three notes: a sustained pitch that slips down just one step and then rises the small interval of a minor third to another sustained pitch.

Now that you’ve been introduced to all of the leitmotivs in the excerpt, follow along with the listening guide. As you listen, notice how prominent the huge orchestra is throughout the scene, how it provides the melodies, and how the strong and large voice of the bass-baritone singing Wotan soars over the top of the orchestra (Wagner’s music required larger voices than earlier opera as well as new singing techniques). See if you can hear the Leitmotivs, there to absorb you in the drama. Remember that this is just one short scene from the midpoint of the approximately fifteen-hour-long tetralogy.

Listening Guide: The Valkyries, Final scene: Wotan’s Farewell

Performed by: Donald McIntyre (Wotan) and Gwyneth Jones (Brünnhilde), accompanied by the Bayreuth Festival Orchestra, conducted by Pierre Boulez

- Composer: Richard Wagner

- Composition: The Valkyries, Final scene: Wotan’s Farewel

- Date: 1870

- Genre: Music drama (or nineteenth-century German opera)

- Form: Through-composed, using Leitmotivs

- Performing Forces: Bass-baritone (Wotan), large orchestra

Nature of Text

(He looks upon her and closes her helmet: his eyes then rest on the form of the sleeper, which he now completely covers with the great steel shield of the Valkyrie. He turns slowly away, then again turns around with a sorrowful look.)

(He strides with solemn decision to the middle of the stage and directs the point of his spear toward a large rock.)

Loge, hear! List to my word!

As I found thee of old, a glimmering flame,

as from me thou didst vanish,

in wandering fire;

as once I stayed thee, stir I thee now!

Appear! come, waving fire,

and wind thee in flames round the fell!

(During the following he strikes the rock thrice with his spear.)

Loge! Loge! appear!

(A flash of flame issues from the rock, which swells to an ever-brightening f iery glow.)

(Flickering flames break forth.)

(Bright shooting flames surround Wotan. With his spear he directs the sea of fire to encircle the rocks; it presently spreads toward the background, where it encloses the mountain in flames.)

He who my spearpoint’s sharpness feareth shall cross not the flaming fire!

(He stretches out the spear as a spell. He gazes sorrowfully back on Brünnhilde. Slowly he turns to depart. He turns his head again and looks back. He diasappears through the fire.)

(The curtain falls.)

What we want you to remember about this composition:

- It uses Leitmotivs

- The orchestra provides an “unending melody” over which the characters sing

- Listen for the specific Leitmotives that have been discussed

| Timing | Performing Forces, Melody, and Texture | Leitmotiv and Text |

| 13:53 | Descending melodic line played in octaves by the lower brass | Wotan’s spear:

Just the orchestra |

| 14:06 | Wotan sings a motivic phrase that ascends; the orchestra ascends, too, supporting his melodic line | Löge, hör! Lausche hieher! Wie zuerst ich dich fand, als feurige Glut, wie dann einst du mir schwandest, als schweifende Lohe; wie ich dich band |

| 14:29 | Appears as Wotan transitions to new words still in the lower brass | Spear again:

Bann ich dich heut’! |

| 14:34 | Trills in the strings and a rising chromatic scale introduce Wotan’s striking of his spear and producing fire introducing the . . . | Fire music:

Herauf, wabernde Loge, umlodre mir feurig den Fels! Loge! Loge! Hieher! |

| 14:58 | Fire music played by the upper woodwinds (flutes, oboes, and clarinets). | Fire music:

Just the orchestra |

| 15:40 | Slower, descending chromatic scale in the winds represents Brünnhilde’s descent into sleep | Sleep:

Just the orchestra |

| 16:04 | As Wotan sings again, his melodic line seems to allude to the sword motive, doubled by the horns and supported by a full orchestra. | Sword motive:

Wer meines Speeres Spitze fürchtet, durchschreite das Feuer nie! |

| 16:31 | Lower brass prominently play the sword motive while the strings and upper woodwinds play motives from the fire music; a gradual decrescendo | Sword motive; fire music continues:

Just the orchestra |

| 17:42 | The horns and trombones play the narrow-raged fate melody as the curtain closes | Fate motive:

Just the orchestra |

Verismo

Verismo, which in this context means “realism,” is the name for a movement that arose in opera near the end of the 19th century. Composers of verismo operas chose realistic settings, often depicting the struggles and drama of common people. In this, they were reacting against the grandiosity and mythological focus of Romanticism. Verismo, like Impressionism, is part of the transition from the Romantic to the Modern era and could justifiably be studied as part of either period.

In terms of subject matter, verismo operas focused not on gods, mythological figures, or kings and queens, but on the average contemporary man and woman and their problems, generally of a romantic, or violent nature. Musically, verismo composers consciously strove for the integration of the opera’s underlying drama with its music. These composers abandoned the “recitative and set-piece structure” of earlier Italian opera. Instead, the operas were through-composed, with few breaks in a seamlessly integrated sung text. While verismo operas may contain arias that can be sung as stand-alone pieces, they are generally written to arise naturally from their dramatic surroundings, and their structure is variable, being based on text that usually does not follow a regular strophic format.

The most famous composers who created works in the verismo style were Giacomo Puccini, Pietro Mascagni, Ruggero Leoncavallo, Umberto Giordano, and Francesco Cilea.

Giacomo Puccini (1858-1924) was an Italian composer, one of the greatest exponents of Verismo (operatic realism,) who virtually brought the history of Italian opera to an end. Puccini’s mature operas focus on tragic love stories; his use of the orchestra was refined, and he established a dramatic structure that balanced action and conflict with moments of repose, contemplation, and lyricism. Puccini’s operas remain exceedingly popular into the 21st century. He was the most popular opera composer in the world at the time of his death. His notable opera include Manon Lescaut (1893), La Bohème (1896), Tosca (1900), Madama Butterfly (1904), The Girl of the Golden West (1910).

Madame Butterfly

La bohème

La bohème is an opera in four acts, composed by Giacomo Puccini to an Italian libretto by Luigi Illica and Giuseppe Giacosa, based on Scènes de la vie de bohème by Henri Murger. The world premiere performance of La bohème was in Turin on 1 February 1896 at the Teatro Regio, conducted by the young Arturo Toscanini. Since then, La bohème has become part of the standard Italian opera repertory and is one of the most frequently performed operas worldwide.

Synopsis

Place: Paris

Time: Around 1830

Act 1

In the four bohemians’ garret

Marcello is painting while Rodolfo gazes out of the window. They complain of the cold. In order to keep warm, they burn the manuscript of Rodolfo’s drama. Colline, the philosopher, enters shivering and disgruntled at not having been able to pawn some books. Schaunard, the musician of the group, arrives with food, wine, and cigars. He explains the source of his riches: a job with an eccentric English gentleman, who ordered him to play his violin to a parrot until it died. The others hardly listen to his tale as they set up the table to eat and drink. Schaunard interrupts, telling them that they must save the food for the days ahead: tonight they will all celebrate his good fortune by dining at Cafe Momus, and he will pay.

The friends are interrupted by Benoît, the landlord, who arrives to collect the rent. They flatter him and ply him with wine. In his drunkenness, he begins to boast of his amorous adventures, but when he also reveals that he is married, they thrust him from the room—without the rent payment—in comic moral indignation. The rent money is divided for their evening out in the Quartier Latin.

Marcello, Schaunard, and Colline go out, but Rodolfo remains alone for a moment in order to finish an article he is writing, promising to join his friends soon. There is a knock at the door. It is a girl who lives in another room in the building. Her candle has blown out, and she has no matches; she asks Rodolfo to light it. She is briefly overcome with faintness, and Rodolfo helps her to a chair and offers her a glass of wine. She thanks him. After a few minutes, she says that she is better and must go. But as she turns to leave, she realizes that she has lost her key.

Her candle goes out in the draught and Rodolfo’s candle goes out too; the pair stumble in the dark. Rodolfo, eager to spend time with the girl, to whom he is already attracted, finds the key and pockets it, feigning innocence. He takes her cold hand (Che gelida manina – “What a cold little hand”) and tells her of his life as a poet, then asks her to tell him more about her life. The girl says her name is Mimì (Sì, mi chiamano Mimì – “Yes, they call me Mimì”), and describes her simple life as an embroiderer. Impatiently, the waiting friends call Rodolfo. He answers and turns to see Mimì bathed in moonlight (duet, Rodolfo and Mimì: O soave fanciulla – “Oh lovely girl”). They realize that they have fallen in love. Rodolfo suggests remaining at home with Mimì, but she decides to accompany him to the Cafe Momus. As they leave, they sing of their newfound love.

Act 1

Please use this link to go to YouTube to watch Act 1 of La Bohème.

Licensing & Attributions

CC licensed content, Original

Authored by: Elliott Jones. Provided by: Santa Ana College.

Located at: http://www.sac.edu

License: CC BY: Attribution

Adapted from “Romantic Opera” from Music 101 by Elliott Jones

Edited and additional material by Jennifer Bill

Focus Compositions were Adapted from “Nineteenth-Century Music and Romanticism” by Jeff Kluball and Elizabeth Kramer from Understanding Music Past and Present

Media Attributions

- Giuseppe Verdi © Giovanni Boldini via. Wikipedia is licensed under a Public Domain license

- Richard Wagner © Wikipedia is licensed under a Public Domain license