Chapter 16: Intro, Art Song, Piano Character Pieces

Early Romantic Era

Introduction

Romantic music is a term denoting an era of Western classical music that began in the late 18th or early 19th century. It was related to Romanticism, the European artistic and literary movement that arose in the second half of the 18th century, and Romantic music in particular dominated the Romantic movement in Germany.

Background: Romanticism

The Romantic movement was an artistic, literary, and intellectual movement that originated in the second half of the 18th century in Europe and strengthened in reaction to the Industrial Revolution. In part, it was a revolt against the social and political norms of the Age of Enlightenment and a reaction against the scientific rationalization of nature. It was embodied most strongly in the visual arts, music, and literature, but had a major impact on historiography, education, and natural history.

One of the first significant applications of the term to music was in 1789, in the Mémoires by the Frenchman André Grétry, but it was E.T.A. Hoffmann who established the principles of musical romanticism, in a lengthy review of Ludwig van Beethoven’s Fifth Symphony published in 1810, and in an 1813 article on Beethoven’s instrumental music. In the first of these essays, Hoffmann traced the beginnings of musical Romanticism to the later works of Haydn and Mozart. It was Hoffmann’s fusion of ideas already associated with the term “Romantic,” used in opposition to the restraint and formality of Classical models, that elevated music, and especially instrumental music, to a position of pre-eminence in Romanticism as the art most suited to the expression of emotions. It was also through the writings of Hoffmann and other German authors that brought German music to the center of musical Romanticism.

Traits

Characteristics often attributed to Romanticism, including musical Romanticism, are:

- a new preoccupation with and surrender to Nature

- a fascination with the past, particularly the Middle Ages and legends of medieval chivalry

- a turn towards the mystic and supernatural, both religious and merely spooky

- a longing for the infinite

- mysterious connotations of remoteness, the unusual and fabulous, the strange and surprising

- a focus on the nocturnal, the ghostly, the frightful, and terrifying

- fantastic seeing and spiritual experiences

- a new attention given to national identity

- emphasis on extreme subjectivism

- interest in the autobiographical

- discontent with musical formulas and conventions

Such lists, however, proliferated over time, resulting in a “chaos of antithetical phenomena,” criticized for their superficiality and for signifying so many different things that there came to be no central meaning. The attributes have also been criticized for being too vague. For example, features of the “ghostly and supernatural” could apply equally to Mozart’s Don Giovanni from 1787 and Stravinsky’s The Rake’s Progress from 1951.

Trends of the 19th Century

Non-Musical Influences

Events and changes that happen in society such as ideas, attitudes, discoveries, inventions, and historical events always affect music. For example, the Industrial Revolution was in full effect by the late 18th century and early 19th century. This event had a very profound effect on music: There were major improvements in the mechanical valves and keys that most woodwinds and brass instruments depend on. The new and innovative instruments could be played with more ease and they were more reliable.

Another development that affected music was the rise of the middle class. Composers before this period lived on the patronage of the aristocracy. Many times their audience was small, composed mostly of the upper class and individuals who were knowledgeable about music. The Romantic composers, on the other hand, often wrote for public concerts and festivals, with large audiences of paying customers, who had not necessarily had any music lessons. Composers of the Romantic Era, like Elgar, showed the world that there should be “no segregation of musical tastes” and that the “purpose was to write music that was to be heard.”

Nationalism

During the Romantic period, music often took on a much more nationalistic purpose. For example, Jean Sibelius’ Finlandia has been interpreted to represent the rising nation of Finland, which would someday gain independence from Russian control. Frédéric Chopin was one of the first composers to incorporate nationalistic elements into his compositions. Joseph Machlis states, “Poland’s struggle for freedom from tsarist rule aroused the national poet in Poland. . . . Examples of musical nationalism abound in the output of the romantic era. The folk idiom is prominent in the Mazurkas of Chopin.” His mazurkas and polonaises are particularly notable for their use of nationalistic rhythms. Moreover, “During World War II the Nazis forbade the playing of . . . Chopin’s Polonaises in Warsaw because of the powerful symbolism residing in these works.” Other composers, such as Bedřich Smetana, wrote pieces that musically described their homelands; in particular, Smetana’s Vltava is a symphonic poem about the Moldau River in the modern-day Czech Republic and the second in a cycle of six nationalistic symphonic poems collectively titled Má vlast (My Homeland). Smetana also composed eight nationalist operas, all of which remain in the repertory. They established him as the first Czech nationalist composer as well as the most important Czech opera composer of the generation who came to prominence in the 1860s.

Sibelius Finlandia

Martha Argerich – Chopin – Mazurka

Smetana the moldau

Romantic Era Explored

Introduction

When people talk about “Classical” music, they usually mean Western art music of any time period. But the Classical period was actually a very short era, basically the second half of the eighteenth century. Only two Classical-period composers are widely known: Mozart and Haydn.

The Romantic era produced many more composers whose names and music are still familiar and popular today: Brahms, Tchaikovsky, Schumann, Schubert, Chopin, and Wagner are perhaps the most well-known, but there are plenty of others who may also be familiar, including Strauss, Verdi, Liszt, Mendelssohn, Puccini, and Mahler. Ludwig van Beethoven, possibly the most famous composer of all, is harder to place. His early works are from the Classical period and are Classical in style. But his later music, including the majority of his most famous music, is just as clearly Romantic.

The term Romantic covers most of the music (and art and literature) of Western civilization from the nineteenth century (the 1800s). But there have been plenty of music written in the Romantic style in the twentieth century (including many popular movie scores), and music isn’t considered Romantic just because it was written in the nineteenth century. The beginning of that century found plenty of composers (Rossini, for example) who were still writing Classical-sounding music. By the end of the century, composers were turning away from Romanticism and searching for new idioms, including post-Romanticism, Impressionism, and early experiments in Modern music.

Background, Development, and Influence

Classical Roots

Sometimes a new style of music happens when composers forcefully reject the old style. Early Classical composers, for example, were determined to get away from what they considered the excesses of the Baroque style. Modern composers also were consciously trying to invent something new and very different.

However, the composers of the Romantic era did not reject Classical music. In fact, they were consciously emulating the composers they considered to be the great classicists: Haydn, Mozart, and particularly Beethoven. They continued to write symphonies, concertos, sonatas, and operas, forms that were all popular with classical composers. They also kept the basic rules for these forms, as well as the rules of rhythm, melody, harmony, harmonic progression, tuning, and performance practice that were established in (or before) the Classical period.

The main difference between Classical and Romantic music came from attitudes toward these “rules”. In the eighteenth century, composers were primarily interested in forms, melodies, and harmonies that provided an easily audible structure for the music. In the first movement of a sonata, for example, each prescribed section would likely be where it belonged, the appropriate length, and in the proper key. In the nineteenth century, the “rules” that provided this structure were more likely to be seen as boundaries and limits that needed to be explored, tested, and even defied. For example, the first movement of a Romantic sonata may contain all the expected sections as the music develops, but the composer might feel free to expand or contract some sections or to add unexpected interruptions between them. The harmonies in the movement might lead away from and back to the tonic just as expected, but they might wander much further afield than a Classical sonata would, before they make their final return.

Different Approaches to Romanticism

One could divide the main part of the Romantic era into two schools of composers. Some took a more conservative approach. Their music is Romantic in style and feeling, but it also still clearly does not want to stray too far from the Classical rules. Schubert, Schumann, Mendelssohn, and Brahms are in this category.

Other composers felt more comfortable with pushing the boundaries of the acceptable. Berlioz, Strauss, and Wagner were all progressives whose music challenged the audiences of their day.

Where to Go After Romanticism?

Perhaps it was inevitable, after decades of pushing at all limits to see what was musically acceptable, that the Romantic era would leave later composers with the question of what to explore or challenge next. Perhaps because there was no clear answer to this question (or several possible answers), many things were happening in music by the end of the Romantic era.

The period that includes the final decades of the nineteenth century and the first decades of the twentieth is sometimes called the post-Romantic era. This is the period when many composers, such as Jean Sibelius, Bela Bartok, and Ralph Vaughan-Williams, concentrated on the traditions of their own countries, producing strongly nationalistic music. Others, such as Mahler and Strauss, were taking Romantic musical techniques to their utmost reasonable limits. In France, Debussy and Ravel were composing pieces that some listeners felt were the musical equivalent of impressionistic paintings. Impressionism and some other -isms such as Stravinsky’s primitivism still had some basis in tonality; but others, such as serialism, rejected tonality and the Classical-Romantic tradition completely, believing that it had produced all that it could. In the early twentieth century, these Modernists eventually came to dominate the art music tradition. Though the sounds and ideals of Romanticism continued to inspire some composers, the Romantic period was essentially over by the beginning of the twentieth century.

Historical Background

Music doesn’t happen in a vacuum. It is affected by other things that are going on in society; ideas, attitudes, discoveries, inventions, and historical events may affect the music of the times.

For example, the “Industrial Revolution” was gaining steam throughout the nineteenth century. This had a very practical effect on music: there were major improvements in the mechanical valves and keys that most woodwinds and brass instruments depended on. The new, improved instruments could be played more easily and reliably, and often had a bigger, fuller, better-tuned sound. Strings and keyboard instruments dominated the music of the Baroque and Classical periods, with small groups of winds added for color. As the nineteenth century progressed and wind instruments improved, more and more winds were added to the orchestra, and their parts became more and more difficult, interesting, and important. Improvements in the mechanics of the piano also helped it usurp the position of the harpsichord to become the instrument that to many people is the symbol of Romantic music.

Another social development that affected music was the rise of the middle class. Classical composers lived on the patronage of the aristocracy; their audience was generally small, upper-class, and knowledgeable about music. The Romantic composer, on the other hand, was often writing for public concerts and festivals, with large audiences of paying customers who had not necessarily had any music lessons. In fact, the nineteenth century saw the first “pop star”-type stage personalities. Performers like Paganini and Liszt were the Taylor Swift of their day.

Romantic Music as an Idea

But perhaps the greatest effect that society can have on an art form is in the realm of ideas.

The music of the Classical period reflected the artistic and intellectual ideals of its time. The form was important, providing order and boundaries. Music was seen as an abstract art, universal in its beauty and appeal, above the pettinesses and imperfections of everyday life. It reflected, in many ways, the attitudes of the educated and the aristocrats of the “Enlightenment” era. Classical music may sound happy or sad, but even the emotions stay within acceptable boundaries.

Romantic-era composers kept the forms of Classical music, but the Romantic composer did not feel constrained by form. Breaking through boundaries was now an honorable goal shared by the scientist, the inventor, and the political liberator. Music was no longer universal; it was deeply personal and sometimes nationalistic. The personal sufferings and triumphs of the composer could be reflected in stormy music that might even place a higher value on emotion than on beauty. Music was not just happy or sad; it could be wildly joyous, terrified, despairing, or filled with deep longings.

It was also more acceptable for music to clearly be from a particular place. Audiences of many eras enjoyed an opera set in a distant country, complete with the composer’s version of exotic-sounding music. But many nineteenth-century composers (including Weber, Wagner, Verdi, Mussorgsky, Rimsky-Korsakov, Grieg, Dvorak, Sibelius, and Albeniz) used folk tunes and other aspects of the musical traditions of their own countries to appeal to their public. Much of this nationalistic music was produced in the post-Romantic period, in the late nineteenth century; in fact, the composers best known for folk-inspired classical music in England (Holst and Vaughan Williams) and the U. S. (Ives, Copland, and Gershwin) were twentieth-century composers who composed in Romantic, post-Romantic, or Neoclassical styles instead of embracing the more severe Modernist styles.

Music can also be specific by having a “program”. Program music is music that, without words, tells a story or describes a scene. Richard Strauss’s tone poems are perhaps the best-known works in this category, but program music has remained popular with many composers throughout the twentieth and twenty-first centuries. Again unlike the abstract, universal music of the Classical composers, Romantic-era program music tried to use music to describe or evoke specific places, people, and ideas. And again, with program music, those Classical rules became less important. The form of the music was chosen to fit with the program (the story or idea), and if it was necessary at some point to choose to stick more closely to the form or the program, the program usually won.

As mentioned above, post-Romantic composers felt ever freer to experiment and break the established rules for form, melody, and harmony. Many modern composers have gone so far that the average listener again finds it difficult to follow. Romantic-style music, on the other hand, with its emphasis on emotions and its balance of following and breaking the musical “rules”, still finds a wide audience.

Art Song

Art songs are not new to the Romantic era. Many composers of earlier historical periods composed songs that would fit the definition of art song as listed on this page. We study art songs now because they were such an integral part of the Romantic repertoire, particularly that of Schubert, Schumann, and Brahms. Because so many art songs in a Romantic style were composed by German composers, we often use the German word for songs, “lieder,” when studying this genre.

Introduction

An art song is a vocal music composition, usually written for one voice with piano accompaniment, and usually in the classical tradition. By extension, the term “art song” is used to refer to the genre of such songs. An art song is most often a musical setting of an independent poem or text, “intended for the concert repertory” “as part of a recital or other relatively formal social occasion.”

Art Song Characteristics

While many pieces of vocal music are easily recognized as art songs, others are more difficult to categorize. For example, a wordless vocalise written by a classical composer is sometimes considered an art song and sometimes not.

Other factors help define art songs:

- Songs that are part of a staged work (such as an opera or a musical) are not usually considered art songs. However, some Baroque arias that “appear with great frequency in recital performance” are now included in the art song repertoire.

- Songs with instruments besides piano and/or other singers are referred to as “vocal chamber music”, and are usually not considered art songs.

- Songs originally written for voice and orchestra are called “orchestral songs” and are not usually considered art songs unless their original version was for solo voice and piano.

- Folksongs are generally not considered art songs unless they are concert arrangements with piano accompaniment written by a specific composer. Several examples of these songs include Aaron Copland’s two volumes of Old American Songs, the Folksong arrangements by Benjamin Britten, and the Siete canciones populares españolas (Seven Spanish Folksongs) by Manuel de Falla.

- There is no agreement regarding sacred songs. Many song settings of biblical or sacred texts were composed for the concert stage and not for religious services; these are widely known as art songs (for example, the Vier ernste Gesänge by Johannes Brahms). Other sacred songs may or may not be considered art songs.

- A group of art songs composed to be performed in a group to form a narrative or dramatic whole is called a song cycle.

Languages and Nationalities

Art songs have been composed in many languages, and are known by several names. The German tradition of art song composition is perhaps the most prominent one; it is known as Lieder. In France, the term Mélodie distinguishes art songs from other French vocal pieces referred to as chansons. The Spanish Canción and the Italian Canzone refer to songs generally and not specifically to art songs.

Art Song Formal Design

The composer’s musical language and interpretation of the text often dictate the formal design of an art song. If all of the poem’s verses are sung to the same music, the song is strophic. Arrangements of folk songs are often strophic, and “there are exceptional cases in which the musical repetition provides dramatic irony for the changing text, or where an almost hypnotic monotony is desired.” Several of the songs in Schubert’s Die schöne Müllerin are good examples of this. If the vocal melody remains the same but the accompaniment changes under it for each verse, the piece is called a “modified strophic” song.

Schubert “An die Musik”

Schubert “Die Forelle”

In contrast, songs in which “each section of the text receives fresh music” are called through-composed. Some through-composed works have some repetition of musical material in them.

Many art songs use some version of the ABA form (also known as “song form”), with a beginning musical section, a contrasting middle section, and a return to the first section’s music.

Art Song Performance and Performers

Performance of art songs in a recital requires some special skills for both the singer and pianist. The degree of intimacy “seldom equaled in other kinds of music” requires that the two performers “communicate to the audience the most subtle and evanescent emotions as expressed in the poem and music.” The two performers must agree on all aspects of the performance to create a unified partnership, making art song performance one of the “most sensitive type(s) of collaboration.”

Even though classical vocalists generally embark on successful performing careers as soloists by seeking out opera engagements, a number of today’s most prominent singers have built their careers primarily by singing art songs, including Dietrich Fischer-Dieskau, Thomas Quasthoff, Ian Bostridge, Matthias Goerne, Susan Graham, and Elly Ameling.

Pianists, too, have specialized in playing art songs with great singers. Gerald Moore, Graham Johnson, and Martin Katz are three such pianists who have specialized in accompanying art song performances.

Two audio of art songs

Thomas Quasthoff, bass-baritone and Daniel Barenboim, piano

Jessye Norman, soprano and Geoffrey Parson, piano

Prominent Composers of Art Songs

British

- John Dowland

- Thomas Campion

- Hubert Parry

- Henry Purcell

- Frederick Delius

- Ralph Vaughan Williams

- Roger Quilter

- John Ireland

- Ivor Gurney

- Peter Warlock

- Michael Head

- Gerald Finzi

- Benjamin Britten

- Morfydd Llwyn Owen

- Michael Tippett

- Ian Venables

- Judith Weir

- George Butterworth

- Francis George Scott

American

- Amy Beach

- Arthur Farwell

- Charles Ives

- Charles Griffes

- Ernst Bacon

- John Jacob Niles

- John Woods Duke

- Ned Rorem

- Richard Faith

- Samuel Barber

- Aaron Copland

- Lee Hoiby

- William Bolcom

- Daron Hagen

- Richard Hundley

- Emma Lou Diemer

Austrian and German

- Joseph Haydn

- Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart

- Franz Schubert

- Hugo Wolf

- Gustav Mahler

- Alban Berg

- Arnold Schoenberg

- Erich Wolfgang Korngold

- Viktor Ullmann

- Carl Philipp Emanuel Bach

- Ludwig van Beethoven

- Johann Carl Gottfried Loewe

- Fanny Mendelssohn

- Felix Mendelssohn

- Robert Schumann

- Clara Schumann

- Johannes Brahms

- Richard Strauss

- Hanns Eisler

- Kurt Weill

French

- Hector Berlioz

- Charles Gounod

- Pauline Viardot

- César Franck

- Camille Saint-Saëns

- Georges Bizet

- Emmanuel Chabrier

- Henri Duparc

- Jules Massenet

- Gabriel Fauré

- Claude Debussy

- Erik Satie

- Albert Roussel

- Maurice Ravel

- Jules Massenet

- Darius Milhaud

- Reynaldo Hahn

- Francis Poulenc

- Olivier Messiaen

Spanish

- Francisco Asenjo Barbieri

- Ramón Carnicer y Batlle

- Ruperto Chapí

- Antonio de la Cruz

- Manuel Fernández Caballero

- Manuel García

- Sebastián de Iradier

- José León

- Cristóbal Oudrid

- Antonio Reparaz

- Emilio Serrano y Ruiz

- Fernando Sor

- Joaquín Valverde

- Amadeo Vives

- Enrique Granados

- Manuel de Falla

- Joaquín Rodrigo

- Joaquín Turina

Italian

- Claudio Monteverdi

- Gioachino Rossini

- Gaetano Donizetti

- Vincenzo Bellini

- Giuseppe Verdi

- Amilcare Ponchielli

- Paolo Tosti

- Ottorino Respighi

- Mario Castelnuovo-Tedesco

- Luciano Berio

- Lorenzo Ferrero

Eastern European

- Franz Liszt—Hungary (nearly all his art song settings are of texts in non-Hungarian European languages, such as French and German)

- Antonín Dvořák—Bohemia

- Leoš Janáček—Bohemia (Czechoslovakia)

- Béla Bartók—Hungary

- Zoltán Kodály—Hungary

- Frédéric Chopin—Poland

- Stanisław Moniuszko—Poland

Nordic

- Edvard Grieg—Norway (set German as well as Norse and Danish poetry)

- Jean Sibelius—Finland (set both Finnish and Swedish)

- Yrjö Kilpinen—Finland

- Wilhelm Stenhammar—Sweden

- Hugo Alfvén—Sweden

- Carl Nielsen—Denmark

Russian

- Mikhail Glinka

- Alexander Borodin

- César Cui

- Nikolai Medtner

- Modest Mussorgsky

- Pyotr Ilyich Tchaikovsky

- Nikolai Rimsky-Korsakov

- Alexander Glazunov

- Sergei Rachmaninoff

- Sergei Prokofiev

- Igor Stravinsky

- Dmitri Shostakovich

Ukrainian

- Vasyl Barvinsky

- Stanyslav Lyudkevych

- Mykola Lysenko

- Nestor Nyzhankivsky

- Ostap Nyzhankivsky

- Denys Sichynsky

- Myroslav Skoryk

- Ihor Sonevytsky

- Yakiv Stepovy

- Kyrylo Stetsenko

Filipino

- Marco Cahulogan

- Carlo Roberto Quijano

- Nicanor Abelardo

- Juan de la Cruz

Afrikaans

- Jellmar Ponticha

- Stephanus Le Roux Marais

Franz Schubert (1797-1828)

Schubert’s life seems to follow, tragically, the cliché of the Romantic artist: a suffering composer who languishes in obscurity, his genius only appreciated after his untimely death. While Schubert did enjoy the respect of a close circle of friends, his music was not widely received during his lifetime. Though we study him in our Romantic module, Schubert does not fit neatly into the Romantic period. Like Beethoven, Schubert is a transitional figure. Some of his music—particularly his earlier instrumental compositions—tends toward a more classical approach. However, the melodic and harmonic innovation in his art songs and later instrumental works sit more firmly in the Romantic tradition. Because his art songs are so clearly Romantic in their inception, and because art songs make up the majority of his compositions, we study him as part of the Romantic era.

Schubert died at 31 but was extremely prolific during his lifetime. His output consists of over six hundred secular vocal works (mainly Lieder), seven complete symphonies, sacred music, operas, incidental music, and a large body of chamber and piano music. Appreciation of his music, while he was alive, was limited to a relatively small circle of admirers in Vienna, but interest in his work increased significantly in the decades following his death. Felix Mendelssohn, Robert Schumann, Franz Liszt, Johannes Brahms, and other 19th-century composers discovered and championed his works. Today, Schubert is ranked among the greatest composers of the late Classical era and early Romantic era and is one of the most frequently performed composers of the early nineteenth century.

Music

Schubert was remarkably prolific, writing over 1,500 works in his short career. The largest number of these are songs for solo voice and piano (over 600). He also composed a considerable number of secular works for two or more voices, namely part songs, choruses, and cantatas. He completed eight orchestral overtures and seven complete symphonies, in addition to fragments of six others. There is a large body of music for solo piano, including fourteen complete sonatas, numerous miscellaneous works, and many short dances. There is also a relatively large set of works for piano duet. There are over fifty chamber works, including some fragmentary works. His sacred output includes seven masses, one oratorio, and one requiem, among other mass movements and numerous smaller compositions. He completed only eleven of his twenty stage works.

It was in the genre of the Lied that Schubert made his most indelible mark. Leon Plantinga remarks, “In his more than six hundred Lieder he explored and expanded the potentialities of the genre as no composer before him.” Prior to Schubert’s influence, Lieder tended toward a strophic, syllabic treatment of the text, evoking the folksong qualities engendered by the stirrings of Romantic nationalism. Among Schubert’s treatments of the poetry of Goethe, his settings of “Gretchen am Spinnrade” (D 118) and “Der Erlkönig” (D 328) are particularly striking for their dramatic content, forward-looking uses of harmony, and their use of eloquent pictorial keyboard figurations, such as the depiction of the spinning wheel and treadle in the piano in “Gretchen” and the furious and ceaseless gallop in “Erlkönig.”

Gretchen am Spinnrade

He composed music using the poems of a myriad of poets, with Johann Wolfgang von Goethe, Johann Mayrhofer, and Friedrich Schiller being the top three most frequent, and others like Heinrich Heine, Friedrich Rückert, and Joseph Freiherr von Eichendorff among many others. Also of particular note are his two song cycles on the poems of Wilhelm Müller, “Die schöne Müllerin” and “Winterreise,” which helped to establish the genre and its potential for musical, poetic, and almost operatic dramatic narrative. His last song cycle published in 1828 after his death, “Schwanengesang,” is also an innovative contribution to German lieder, as it features poems by different poets, namely Ludwig Rellstab, Heine, and Johann Gabriel Seidl. The Wiener Theaterzeitung (Vienna Theater Journal), writing about “Winterreise” at the time, commented that it was a work that “none can sing or hear without being deeply moved.” Antonín Dvořák wrote in 1894 that Schubert, whom he considered one of the truly great composers, was clearly influential on shorter works, especially Lieder and shorter piano works: “The tendency of the romantic school has been toward short forms, and although Weber helped to show the way, to Schubert belongs the chief credit of originating the short models of pianoforte pieces which the romantic school has preferably cultivated. […] Schubert created a new epoch with the Lied. […] All other songwriters have followed in his footsteps.”

Der Erlkönig

Poem Summary

“Erlkönig” (also called “Der Erlkönig“) is a poem by Johann Wolfgang von Goethe. It was originally composed by Goethe as part of a 1782 Singspiel entitled Die Fischerin.

An anxious young boy is being carried home at night by his father on horseback. As the poem unfolds, the son seems to see and hear beings his father does not; the reader cannot know if the father is indeed aware of the presence, but he chooses to comfort his son, asserting reassuringly naturalistic explanations for what the child sees—a wisp of fog, rustling leaves, shimmering willows. Finally, the child shrieks that he has been attacked. The father makes faster for their home. There he recognizes that the boy is dead.

Schubert’s Lied

Franz Schubert composed his Lied, “Der Erlkönig,” for solo voice and piano in 1815, setting text from Goethe’s poem. Schubert revised the song three times before publishing his fourth version in 1821 as his Opus 1. The song was first performed in concert on 1 December 1820 at a private gathering in Vienna and received its public premiere on 7 March 1821 at Vienna’s Theater am Kärntnertor.

The four characters in the song—narrator, father, son, and the Erlking—are all sung by a single vocalist. Schubert placed each character largely in a different vocal range, and each has its own rhythmic nuances; in addition, most singers endeavor to use a different vocal coloration for each part. The piece modulates frequently, although each character changes between minor or major modes depending on how each character intends to interact with the other characters.

The Narrator lies in the middle range and begins in the minor mode.

The Father lies in the lower range and sings in both minor and major modes.

The Son lies in a higher range, also in the minor mode.

The Erlking’s vocal line, in a variety of major keys, undulates up and down to arpeggiated accompaniment, providing the only break from the ostinato bass triplets in the accompaniment until the boy’s death. When the Erlking first tries to take the Son with him he sings in C major. When it transitions from the Erlking to the Son the modulation occurs and the Son sings in g minor. The Erlking’s lines are typically sung in a softer dynamic in order to contribute to a different color of sound than that which is used previously. Schubert marked it pianissimo in the manuscript to show that the color needed to change.

A fifth character, the horse, is implied in rapid triplet figures played by the pianist throughout the work, mimicking hoof beats.

“Der Erlkönig” starts with the piano rapidly playing triplets to create a sense of urgency and simulate the horse’s galloping. The left hand of the piano part introduces a low-register leitmotif composed of successive triplets. The right hand consists of triplets throughout the whole piece, up until the last three bars. The constant triplets drive forward the frequent modulations of the peace as it switches between the characters. This leitmotif, dark and ominous, is directly associated with the Erlkönig and recurs throughout the piece.

As the piece continues, each of the son’s pleas becomes louder and higher in pitch than the last.

Near the end of the piece the music quickens and then slows as the father spurs his horse to go faster and then arrives at his destination. The absence of the piano creates multiple effects on the text and music. The silence draws attention to the dramatic text and amplifies the immense loss and sorrow caused by the son’s death. This silence from the piano also delivers shock experienced by the father upon the realization that he had just lost his son to the elf king, despite desperately fighting to save the son from the elf king’s grasp.

The piece is regarded as extremely challenging to perform due to the multiple characters the vocalist is required to portray, as well as its difficult accompaniment, involving rapidly repeated chords and octaves which contribute to the drama and urgency of the piece.

Der Erlkönig is a through-composed piece, meaning that with each line of text, there is new music. Although the melodic motives recur, the harmonic structure is constantly changing and the piece modulates within characters.

The elf king character remains mainly in the major mode because he is trying to seduce the son into giving up on life. Using a major mode creates an effect where the elf king can portray a warm and inviting aura to convince the son that the afterlife promises great pleasures and fortunes.

The son always starts singing in the minor mode and usually stays in it for his whole line. This is used to represent his fear of the elf king. Every time he sings the famous line “Mein Vater” he sings it one step higher in each verse, starting first at a D and going up to an F on his final line. This indicates his urgency in trying to get his father to believe him as the elf king gets closer.

Most of the Father’s lines begin in minor and end in major as he tries to reassure his son by providing rational explanations for his son’s “hallucinations” and dismissing the Elf-king. The constant in major and minor for the father may also represent the constant struggle and loss of control as he tries to save his son from the elf king’s persuasion.

The rhythm of the piano accompaniment also changes within the characters. The first time the Elf-king sings, the galloping motive disappears. However, when the Elf-king sings again, the piano accompaniment is arpeggiating rather than playing chords. The disappearance of the galloping motive is also symbolic of the son’s hallucinatory state.

Focus Composition

Schubert, The Erlking (1815)

The Erlking tells the story of a father who is rushing on horseback with his ailing son to the doctor. Delirious from fever, the son hears the voice of the Erlking, a grim reaper sort of king of the fairies, who appears to young children when they are about to die, luring them into the world beyond. The father tries to reassure his son that his fear is imagined, but when the father and son reach the courtyard of the doctor’s house, the child is found to be dead.

As you listen to the song, follow along with its words. You may have to listen several times in order to hear the multiple connections between the music and the text. Are the ways in which you hear the music and text interacting beyond those pointed out in the listening guide?

Listening Guide: Der Erlkönig (in English, The Erlking)

Performed by: Philippe Sly, bass-baritone and Maria Fuller, piano

- Composer: Franz Schubert

- Composition: Der Erlkönig (in English, The Erlking)

- Date: 1815

- Genre: Art song

- Form: Through-composed

- Performing Forces: Solo voice and piano

What we want you to remember about this composition:

- It is an art song that sets a poem for solo voice and piano

- The poem tells the story of three characters, who are depicted in the music through changes in melody, harmony, and range.

- The piano sets the general mood and supports the singer by depicting images from the text.

Other things to listen for:

- Piano accompaniment at the beginning that outlines a minor scale (perhaps the wind)

- Repeated fast triplet pattern in the piano, suggesting urgency and the running horse

- Shifts of the melody line from high to low range, depending on the character “speaking”

- Change of key from minor to major when the Erlking sings

- The slowing note values at the end of the song and the very dissonant chords

Original Text

Wer reitet so spät dur ch Nacht und Wind?

Es ist der Vater mit seinem Kind.

Er hat den Knaben wohl in dem Arm,

Er faßt ihn sicher, er hält ihn warm.

Mein Sohn, was birgst du so bang dein Gesicht?

Siehst Vater, du den Erlkönig nicht!

Den Erlenkönig mit Kron’ und Schweif?

Mein Sohn, es ist ein Nebelstreif.

Du liebes Kind, komm geh’ mit mir!

Gar schöne Spiele, spiel ich mit dir,

Manch bunte Blumen sind an dem Strand,

Meine Mutter hat manch gülden Gewand.

Mein Vater, mein Vater, und hörest du nicht,

Was Erlenkönig mir leise verspricht?

Sei ruhig, bleibe ruhig, mein Kind,

In dürren Blättern säuselt der Wind.

Willst feiner Knabe du mit mir geh’n?

Meine Töchter sollen dich warten schön,

Meine Töchter führen den nächtlichen Reihn

Und wiegen und tanzen und singen dich ein.

Mein Vater, mein Vater, und siehst du nicht dort

Erlkönigs Töchter am düsteren Ort?

Mein Sohn, mein Sohn, ich seh’es genau:

Es scheinen die alten Weiden so grau.

Ich lieb dich, mich reizt deine schöne Gestalt, Und bist du nicht willig, so brauch ich Gewalt!

Mein Vater, mein Vater, jetzt faßt er mich an,

Erlkönig hat mir ein Leids getan.

Dem Vater grauset’s, er reitet geschwind,

Er hält in den Armen das ächzende Kind,

Erreicht den Hof mit Mühe und Not,

In seinen Armen das Kind war tot.

Translation

Who rides there so late through the night and wind? The father it is, with his infant so dear;

He holds the boy tightly clasped in his arm,

He holds him safely, he keeps him warm.

“My son, why do you anxiously hide your face?”

“Look, father, is it not the Erlking!

The Erlking with crown and with train?”

“My son, it is the mist over the clouds.”

“Oh, come, dear child! oh, come with me!

So many games I will play there with thee;

On my shoreline, lovely flowers their blossoms unfold,

My mother has many a gold garment.”

“My father, my father, and do you not hear

The words that the Erlking softly promises me?”

“Be calm, stay calm, my child,

The wind sighs through the dry leaves.”

“Will you come with me, my child?

My daughters shall wait on you;

My daughters dance each night,

And will cradle you and dance and sing to you.”

“My father, my father, and do you not see,

The Erl-King’s daughters in this dreary place?”

“My son, my son, I see it aright,

The old fields appear so gray.”

“I love you, I’m charmed by your lovely form!

And if you’re unwilling, then force I’ll employ.”

“My father, my father, he seizes me fast,

Full sorely the Erl-King has hurt me at last.”

The father, horrified, rides quickly,

He holds in his arms the groaning child:

He reaches his courtyard with toil and trouble,—

In his arms, the child was dead.

| Timing | Performing Forces, Melody, and Texture | Form and Text |

| 0:00 | Piano introduction Opens with a fast tempo melody that begins low in the register, ascends through the minor scale, and then falls. Accompanied by repeated triplet octaves. The ascending/ descending melody may represent the wind. The minor key suggests a serious tone. The repeated octaves using fast triplets may suggest the running horse and the urgency of the situation. | |

| 0:23 | Voice and piano from here to the end; Performing forces are voice and piano in homophonic texture from here to the end. Melody falls in the middle of the singer’s range and is accompanied by the repeated octave triplets. | Narrator: Who rides so late through night and wind? |

| 0:55 | Melody drops lower in the singer’s range. | Father: My son, why are you frightened? |

| 1:03 | Melody shifts to a higher range | Son: Do you see the Erlking, father? |

| 1:19 | Melody lower in range. | Father: It is the fog. |

| 1:27 | The key switches to major, perhaps to suggest the friendly guise assumed by the Erlking. Note also the softer dynamics and lighter arpeggios in the piano accompaniment | The Erlking: Lovely child, come with me… |

| 1:50 | Back in minor the melody hovers around one note high in the singer’s register; the minor mode reflects the son’s fear, as does the melody, which repeats the same note, almost as if the son is unable to sing another | Son: My father, father, do you not hear it… |

| 2:03 | Melody lower in range | Father: Be calm, my child, the wind blows the dry leaves… |

| 2:13 | Back to a major key and piano dynamics for more from the Erlking | The Erlking: My darling boy, won’t you come with me… |

| 2:30 | Back to a minor key and the higher-ranged melody that hovers around one pitch for the son’s retort. | Son: My father, can you not see him there? |

| 2:43 | Melody lower in range and return of the louder repeated triplets | Father: My son, I see well the moonlight on the grey meadows…. |

| 3:00 | Momentarily in major and then back to minor as the Erlking threatens the boy | The Erlking: I love you…if you do not freely come, I will use force… |

| 3:11 | Back to a minor key and the higher-ranged melody that hovers around one pitch. | Son: My father, he has seized me… |

| 3:26 | Back to a mid-range melody; the notes in the piano get faster and louder. | Narrator: The father, filled with horror, rides fast |

| 3:40 | Piano accompaniment slows down; dissonant and minor chords pervasive; song ends with a strong cadence in the minor key; Slowing down of the piano accompaniment may echo the slowing down of the horse. The truncated chords and strong final minor chords buttress the announcement that the child is dead. | Narrator: They arrive at the courtyard. In his father’s arms, the child was dead. |

Josephine Lang (1815-1880)

By MARCIA J. CITRON

Josephine Lang came from a musical home in Munich, where her father was a court musician and her mother, Regina Hitzelberger, was a court opera singer. Although the young Josephine started out on the piano, she soon immersed herself in song, as both interpreter and creator. Her earliest lieder dates from her thirteenth year, and this genre was to occupy her compositional talents almost exclusively.

Momentous in Lang’s life were her encounters with Felix Mendelssohn, in 1830 and again in 1831, when he visited Munich on his extended tour of Europe. Here was a gifted fifteen-year-old, almost entirely self-taught, whose lieder, singing, and angelic presence evoked an enraptured response from the sensitive young musician. His sisters Fanny and Rebecka must have been surprised by the intensity of his enthusiasm— they knew him as a cool, level-headed judge of the contemporary scene. In any case, such encouragement undoubtedly spurred on Lang in her compositional endeavors. From the mid-i830S to the early 1840s she was extremely prolific, producing approximately one-third of her total output of lieder. She tended to select texts that mirrored the feelings and events of her own life: “They are my diary,” she wrote in 1835.

It was in this period that her music began to be published, eliciting generally favorable reviews. An assessment by Robert Schumann of “Das Traumbild,” which he saw well before its publication, appeared in his journal Neue Zeitschrift für Musik in 1837. In 1840 Lang met her future husband, the Swabian poet Reinhard Kostlin, whose poems she would set in numerous lieder. After their marriage in 1842, they moved to Tubingen. There Lang devoted herself mainly to domestic activities, and her creative pursuits decreased markedly. Kostlin’s death in 1856 left her with the heavy burden of caring and providing for their six children, and she turned to composing and publication for financial reasons. But now Lang’s style was somewhat out of step with contemporary currents, and as a result, she had considerable difficulty getting her music published. Through the assistance of a friend of Mendelssohn’s, the influential Ferdinand Hiller, she managed to secure the publication of some lieder and thereby support her family. Her death occasioned a retrospective collection of 40 songs, many of them hitherto unpublished, by Breitkopf & Härtel in 1882.

Traumbild, Op. 28, No. 1

Robert Schumann (1810–1856)

Robert Schumann was a German composer and influential music critic. He is widely regarded as one of the greatest composers of the Romantic era. Schumann left the study of law, intending to pursue a career as a virtuoso pianist. He had been assured by his teacher Friedrich Wieck that he could become the finest pianist in Europe, but a hand injury ended this dream. Schumann then focused his musical energies on composing.

Schumann’s published compositions were written exclusively for the piano until 1840; he later composed works for piano and orchestra; many Lieder; four symphonies; an opera; and other orchestral, choral, and chamber works. Works such as Kinderszenen, Album für die Jugend, Blumenstück, the Piano Sonatas, and Albumblätter are among his most famous. His writings about music appeared mostly in the Neue Zeitschrift für Musik (New Journal for Music), a Leipzig-based publication which he jointly founded.

In 1840, against the wishes of her father, Schumann married Friedrich Wieck’s daughter Clara, following a long and acrimonious legal battle, which found in favor of Clara and Robert. Clara Schumann was as formidable a musician as her husband. She composed music and had a considerable concert career as a pianist, the earnings from which formed a substantial part of her father’s fortune.

Schumann suffered from a lifelong mental disorder, first manifesting itself in 1833 as a severe melancholic depressive episode, which recurred several times alternating with phases of ‘exaltation’ and increasingly also delusional ideas of being poisoned or threatened with metallic items. After a suicide attempt in 1854, Schumann was admitted to a mental asylum, at his own request. Diagnosed with “psychotic melancholia”, Schumann died two years later in 1856 without having recovered from his mental illness.

Frauenliebe und leben

Frauenliebe und leben (A Woman’s Love and Life) is a cycle of poems by Adelbert von Chamisso, written in 1830. They describe the course of a woman’s love for her man, from her point of view, from first meeting through marriage to his death, and after. Selections were set to music as a song cycle by masters of German Lied, namely Carl Loewe, Franz Paul Lachner, and Robert Schumann. The setting by Schumann (his opus 42) is now the most widely known.

Schumann wrote his setting in 1840, a year in which he wrote so many lieder (including two other song cycles: Liederkreis Op. 24 and Op. 39, Dichterliebe), that it is known as his “year of song”. There are eight poems in his cycle, together telling a story from the protagonist first meeting her love, through their marriage, to his death. They are:

“Seit ich ihn gesehen” (“Since I Saw Him”)

“Er, der Herrlichste von allen” (“He, the Noblest of All”)

“Ich kann’s nicht fassen, nicht glauben” (“I Cannot Grasp or Believe It”)

“Du Ring an meinem Finger” (“You Ring Upon My Finger”)

“Helft mir, ihr Schwestern” (“Help Me, Sisters”)

“Süßer Freund, du blickest mich verwundert an” (“Sweet Friend, You Gaze”)

“An meinem Herzen, an meiner Brust” (“At My Heart, At My Breast”)

“Nun hast du mir den ersten Schmerz getan” (“Now You Have Caused Me Pain for the First Time”)

Schumann’s choice of text was probably inspired in part by events in his personal life. He had been courting Clara Wieck but had failed to get her father’s permission to marry her. In 1840, after a legal battle to make such permission unnecessary, he finally married her.

The songs in this cycle are notable for the fact that the piano has a remarkable independence from the voice. Breaking away from the Schubertian ideal, Schumann has the piano contain the mood of the song in its totality. Another notable characteristic is the cycle’s cyclic structure, in which the last movement repeats the theme of the first.

Schumann: Frauenliebe und leben (A Woman’s Love and Life)

The Piano and Its Character Pieces of the 19th Century

The Piano

The invention of the piano is credited to Bartolomeo Cristofori (1655–1731) of Padua, Italy, who was an expert harpsichord maker and was well acquainted with the body of knowledge on stringed keyboard instruments. The piano was probably formed as an attempt to combine loudness with control, avoiding the trade-offs of available instruments.

Technical innovations continued to be added to the piano as various instrument makers experimented with ways to improve the instrument’s mechanical function and tonal expression in the 18th century. By the late 19th century the piano had evolved into the powerful 88-key instrument we recognize today. It is important to remember that much of the music of the Classical era was composed for a type of instrument (the fortepiano) that is rather different from the instrument on which it is now played. Even the music of the Romantic period, including that of Chopin, Schumann, and Brahms, was written for pianos substantially different from modern pianos.

Character Pieces

Character pieces for the piano emerged in the 19th century as a significant genre within Romantic music. These compositions aimed to capture specific moods, emotions, or scenes, often drawing inspiration from literature, nature, or personal experiences. Characterized by their brevity and expressive depth, these pieces allowed composers to convey intricate emotions through the piano’s versatile voice.

Composers such as Robert Schumann, Frédéric Chopin, Felix Mendelssohn, and Edvard Grieg were prominent contributors to this genre. Each composer infused their unique style and cultural influences into their character pieces, resulting in a rich diversity of musical expressions.

Schumann’s “Carnaval” depicted masked revelry and introspection through a series of contrasting miniatures, while Chopin’s nocturnes and preludes conveyed an array of sentiments, from melancholy to exuberance. Mendelssohn’s “Songs Without Words” were lyrical, song-like pieces that conveyed a sense of intimacy and introspection, and Grieg’s “Lyric Pieces” drew inspiration from Norwegian folk traditions and landscapes.

Mendelssohn: Song without words

Grieg: Lyric Pieces Op. 12, No.5

Clara Schumann (1819-1896)

Clara Schumann was a German pianist, composer, and piano teacher. Regarded as one of the most distinguished pianists of the Romantic era, she exerted her influence over the course of a 61-year concert career, changing the format and repertoire of the piano recital by lessening the importance of purely virtuosic works. She also composed solo piano pieces, a piano concerto (her Op. 7), chamber music, choral pieces, and songs.

She grew up in Leipzig, where both her father Friedrich Wieck, and her mother Mariane were pianists and piano teachers. In addition, her mother was a singer. Clara was a child prodigy and was trained by her father. She began touring at age eleven, and was successful in Paris and Vienna, among other cities. She married the composer Robert Schumann at age 20, and While Robert was gaining recognition as a composer and conductor, Clara’s composition and performance activities were restricted by her giving birth to eight children. Together, they encouraged Johannes Brahms and maintained a close relationship with him. She gave the public premieres of many works by her husband and by Brahms.

After Robert Schumann’s early death, she continued her concert tours in Europe for decades, frequently with the violinist Joseph Joachim and other chamber musicians. Beginning in 1878, she was an influential piano educator at Dr. Hoch’s Konservatorium in Frankfurt, where she attracted international students. She also edited the publication of her husband’s work. After Robert’s death, Clara spent the rest of her life supporting her children and grandchildren through her public appearances and teaching. Her busy calendar may have been one of the reasons why she did not compose after her husband’s death. Clara Schumann died in Frankfurt but was buried in Bonn beside her husband.

Focus Composition:

Clara Schumann, Ballade in D minor

This character piece is one written by Clara Schumann between 1834 and 1836 and published as one piece in the collection Soirées Musicales in 1836 (a soirée was an event generally held in the home of a well-to-do lover of the arts where musicians and other artists were invited for entertainment and conversation). Clara called this composition Ballade in D minor. The meaning of the title seems to have been vague almost by design, but, most broadly considered, a ballade referred to a composition thought of as a narrative. As a character piece, it tells its narrative completely through music. Several contemporary composers wrote ballades of different moods and styles; Clara’s “Ballade” shows some influence of Chopin.

Clara’s Ballade has a homophonic texture and starts in a minor key. Its themes/phrases start multiple times, each time slightly varied. You may hear what we call musical embellishments. These are notes the composer adds to a melody to provide variations. You might think of them like jewelry on a dress or ornaments on a Christmas tree. One of the most famous sorts of ornaments is the trill, in which the performer rapidly and repeatedly alternates between two pitches. We also talk of turns, in which the performer traces a rapid stepwise ascent and descent (or descent and ascent) for effect. You should also note that as the pianist in this recording plays, they seem to hold back notes at some moments and rush ahead at others: this is called rubato, that is, the robbing of time from one note to give it to another. We will see the use of rubato even more prominently in the music of Chopin.

Listening Guide: Ballade in D minor, Op. 6, no. 4

Performed by: Hye-seon Lim, piano

- Composer: Clara Wieck Schumann

- Composition: Ballade in D minor, Op. 6, no. 4

- Date: 1836

- Genre: Piano character piece

- Form: ABA

- Nature of Text: This is a ballade, that is, a composition with narrative premises

- Performing Forces: Solo piano

What we want you to remember about this composition:

- A lyrical melody over chordal accompaniment making this homophonic texture

- A moderate to slow tempo

- In duple time (in this case, four beats for each measure)

Other things to listen for:

- Musical themes that develop and repeat but are always varied

- Musical embellishments in the form of trills and turns

| Timing | Performing Forces, Melody, and Texture | Text and Form |

| 0:00 | Theme starts three times before taking off; melody ascends and uses ornaments for variations; in D minor. Piano dynamics, slow tempo, duple time. | A |

| 0:55 | 0:55 Transitional idea using trills (extended ornaments). | No Data |

| 1:26 | New musical idea repeated a couple of times with variation. Ascending phrases crescendo and descending phrases decrescendo. | No Data |

| 2:09 | Transitional idea returns. Slightly louder. | No Data |

| 2:22 | Repeated note theme. More passionate and louder then subsiding in dynamics. | No Data |

| 2:48 | First theme returns in D minor and then is varied. Piano with a crescendo to fortissimo and then a return to piano. | B |

| 4:15 | Piano dynamics quickly altered by crescendos and decrescendos. | A’ |

| 4:32 | Return of rhythmic motive from opening. A section and then varied Dynamics move from soft to loud to soft. | Coda |

Maria Agata Szymanowska (1789-1831)

By NANCY FIERRO, CSJ

Maria Agata Szymanowska, a contemporary of Beethoven and Schubert, was the first Polish pianist of stature. Her playing won the title “Royal Pianist of the Court of Russia” and the admiration of both Liszt and Chopin in their younger years. Her many piano compositions, published during her lifetime, are significant in the history of Polish music before Chopin.

The daughter of Barbara Lanckoronska and middle-class merchant Franciscek Wolowski, Maria exhibited a precocious talent. With only scant keyboard instruction, the young girl seated at the spinet would entertain family guests with improvisations on her own themes. Between 1789 and 1802, the obscure composers Antoni Lisowski and Tomasz Gremm taught her piano; and Josef Eisner, Franciszek Lessel, John Field, and Johann Nepomuk Hummel occasionally provided her with advice about performance or prompted revisions of her compositions. Otherwise, it appears that Maria was largely self taught.

In 1810, the young pianist made her debut in Warsaw. In the same year,, she married a wealthy landowner, Josef Szymanowski. By 1815, she was in great demand for public concerts, but her frequent appearances were offensive to her husband. His continued disapproval caused Maria to separate from him in 1820 and take her three children with her. She earned her living through concerts and lectures on piano technique. With many performances behind her and some of her works published, she began regular appearances throughout both Eastern and Western Europe, returning intermittently to her beloved Warsaw.

During her successful concert career from 1810 to 1828, Szymanowska included many of her own works in her programs. She wrote more than 100 compositions: vocal music, chamber music, and a large body of piano music. In an era when society placed little value on compositions by women, it is remarkable that Szymanowska’s works found immediate publication—by Breitkopf and Hartel in Leipzig and by publishers in Paris, Warsaw, St. Petersburg, Moscow, Kiev, and Odessa.

Between the years 1828 and 1831 Szymanowska had more time to devote to personal activities. Until then, responsibility for her children, the demands of an active social life, and the exigencies of a professional career demanded most of her attention. But in her permanent home in St. Petersburg, she was free to pursue some long-delayed projects. One of these activities was collecting her compositions and copying them into one album. It is possible that for the first time, she had sufficient leisure to compose more-sophisticated pieces.

On the afternoon of July 23, 1831, Maria Agata Szymanowska suddenly fell ill with cholera. She died the following morning and was buried in what is now Leningrad.

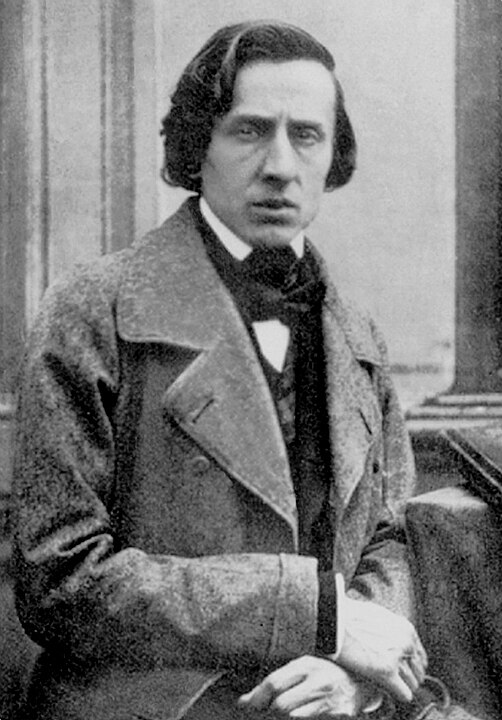

Frédéric Chopin (1810 – 1849)

Frédéric François Chopin, born Fryderyk Franciszek Chopin, was a Polish composer and virtuoso pianist of the Romantic era, who wrote primarily for the solo piano. He gained and has maintained renown worldwide as one of the leading musicians of his era, whose “poetic genius was based on a professional technique that was without equal in his generation.” A child prodigy, he completed his musical education and composed many of his works in Warsaw before leaving Poland at the age of 20, less than a month before the outbreak of the November 1830 Uprising.

At the age of 21, he settled in Paris. Thereafter, during the last 18 years of his life, he gave only some 30 public performances, preferring the more intimate atmosphere of the salon. He supported himself by selling his compositions and teaching piano, for which he was in high demand. Chopin formed a friendship with Franz Liszt and was admired by many of his musical contemporaries, including Robert Schumann. In 1835 he obtained French citizenship. In his last years, he was financially supported by his admirer Jane Stirling, who also arranged for him to visit Scotland in 1848. Throughout most of his life, Chopin suffered from poor health. He died in Paris in 1849, probably of tuberculosis.

All of Chopin’s compositions include the piano. Most are for solo piano, though he also wrote two piano concertos, a few chamber pieces, and some songs with Polish lyrics. His keyboard style is highly individual and often technically demanding; his own performances were noted for their nuance and sensitivity. Chopin invented the concept of an instrumental ballade. His major piano works include sonatas, mazurkas, waltzes, nocturnes, polonaises, études, impromptus, scherzos, and preludes, some published only after his death. Many contain elements of both Polish folk music and of the classical tradition of J. S. Bach, Mozart, and Schubert, the music of all of whom he admired. His innovations in style, musical form, and harmony, and his association of music with nationalism, were influential throughout and after the late Romantic period.

Both in his native Poland and beyond, Chopin’s music, his status as one of music’s earliest superstars, his association (if only indirect) with political insurrection, his love life, and his early death have made him, in the public consciousness, a leading symbol of the Romantic era. His works remain a staple in the solo piano repertoire.

Focus composition:

Chopin, Mazurka in F Minor, Op. 7, no. 1 (1832)

The composition on which we will focus is the Mazurka in F minor, Op. 7, no. 1, which was published in Leipzig in 1832 and then in Paris and London in 1833. The mazurka is a Polish dance, and mazurkas were rather popular in Western Europe as exotic stylized dances. Mazurkas are marked by their triple meter in which beat two rather than beat one gets the stress. They are typically composed in strains and are homophonic in texture. Chopin sometimes incorporated folk-like sounds in his mazurkas, sounds such as drones and augmented seconds. A drone is a sustained pitch or pitches. The augmented second is an interval that was commonly used in Eastern European folk music but very rarely in the tonal music of Western European composers.

All of these characteristics can be heard in the Mazurka in F minor, Op. 7, no. 1, together with the employment of rubato. Chopin was the first composer to widely request that pianists use rubato when playing his music. Rubato is a musical term used to describe a flexible and expressive alteration of tempo within a musical phrase or passage. It involves a slight pushing and pulling of the rhythm, allowing for temporary deviations from the strict and metronomic pulse. In essence, rubato grants the performer the freedom to speed up or slow down the tempo for expressive purposes, while maintaining the overall sense of the piece.

Listening Guide: Mazurka in F minor, Op. 7, no. 1

Performed by: Arthur Rubinstein on piano

- Composer: Fryderyk Chopin

- Composition: Mazurka in F minor, Op. 7, no. 1

- Date: 1836

- Genre: Piano character piece

- Form: aaba’ba’ca’ca’

- Nature of Text: The title indicates a stylized dance based on the Polish mazurka

- Performing Forces: Solo piano

What we want you to remember about this composition:

- This mazurka is in triple time with emphasis on beat two

- The texture is homophonic

- Chopin asks the performer to use rubato

Other things to listen for:

- Its “c” strain uses a drone and augmented seconds

- Its form is aaba’ba’ca’ca’

| Timing | Performing Forces, Melody, and Texture | Text and Form |

| 0:00 | Triple-meter theme ascends up the scale and then descends and then repeats; brief ornaments on beat two of the measure. In F minor, with homophonic boom-chuck texture. | aa |

| 0:33 | After a contrasting theme that oscillates, part of the first theme returns in a’. | ba’ |

| 1:01 | No Data | ba’ |

| 1:30 | Folk-like melody using augmented seconds. Listen for the drone as well as rubato (which Chopin asks for here). | c |

| 1:44 | No data | a |

| 2:01 | C returns, then a. | ca |

Licensing & Attributions

CC licensed content, Original

Authored by: Elliott Jones. Provided by: Santa Ana College.

Located at: http://www.sac.edu

License: CC BY: Attribution

Adapted from “Early Romantic Era” from Music 101 by Elliott Jones

Edited and additional material by Jennifer Bill

Focus Compositions were Adapted from “Nineteenth-Century Music and Romanticism” by Jeff Kluball and Elizabeth Kramer from Understanding Music Past and Present

Josephine Lang and Maria Agata Szymanowska taken from Briscoe, James R. Historical Anthology of Music by Women. Indiana University Press, 1986. Project MUSE muse.jhu.edu/book/84778.

Media Attributions

- Franz Schubert_by_Wilhelm_August_Rieder_1875 © Wilhelm August Rieder via. Wikipedia is licensed under a Public Domain license

- Josephine Caroline Lang © Wikipedia is licensed under a Public Domain license

- Robert schumann © Wikipedia is licensed under a Public Domain license

- Clara Schumann © Andreas Staub via. Wikipedia is licensed under a Public Domain license

- Maria Szymanowska © Wikipedia is licensed under a Public Domain license

- Frederic Chopin 1849 © Wikipedia is licensed under a Public Domain license