Chapter 9: The Birth of Opera

The Birth of Opera

The beginning of the Baroque Period is in many ways synonymous with the birth of opera. Music drama had existed since the Middle Ages (and perhaps even earlier), but around 1600, noblemen increasingly sponsored experiments that combined singing, instrumental music, and drama in new ways. As we have seen in previous chapters, Renaissance Humanism led to new interest in ancient Greece and Rome. Scholars as well as educated noblemen read descriptions of the emotional power of ancient dramas, such as those by Sophocles, which began and ended with choruses.

One particularly active group of scholars and aristocrats interested in the ancient world was the Florentine Camerata, so called because they met in the rooms (or camerata) of a nobleman in Florence, Italy. This group, which included Vicenzo Galilei, father of Galileo Galilei, speculated that the reason for ancient drama’s being so moving was its having been entirely sung to a sort of declamatory style that was midway between speech and song. Although today we believe that actually only the choruses of ancient drama were sung, these circa 1600 beliefs led to collaborations with musicians and the development of opera.

Less than impressed by the emotional impact of the rule-driven polyphonic church music of the Renaissance, members of the Florentine Camerata argued that a simple melody supported by sparse accompaniment would be more moving. They identified a style that they called recitative, in which a single individual would sing a melody line that follows the inflections and rhythms of speech (see figure one with an excerpt of basso continuo). This individual would be accompanied by just one or two instruments: a keyboard instrument, such as a harpsichord or small organ, or a plucked string instrument, such as the lute. The accompaniment was called the basso continuo.

Basso continuo is a continuous bass line over which the harpsichord, organ, or lute added chords based on numbers or figures that appeared under the melody that functioned as the bass line, would become a defining feature of Baroque music. This system of indicating chords by numbers was called figured bass, and allowed the instrumentalist more freedom in forming the chords than had every note of the chord been notated. The flexible nature of basso continuo also underlined its supporting nature. The singer of the recitative was given license to speed up and slow down as the words and emotions of the text might direct, with the instrumental accompaniment following along. This method created a homophonic texture, which consists of one melody line with accompaniment.

Composers of early opera combined recitatives with other musical numbers such as choruses, dances, arias, instrumental interludes, and the overture. The choruses in opera were not unlike the late Renaissance madrigals that we studied in chapter three. Operatic dance numbers used the most popular dances of the day, such as pavanes and galliards. Instrumental interludes tended to be sectional, that is, having different sections that sometimes repeated, as we find in other instrumental music of the time. Operas began with an instrumental piece called the Overture. Like recitatives, arias were homophonic compositions featuring a solo singer over accompaniment. Arias, however, were less improvisatory. The melodies sung in arias almost always conformed to a musical meter, such as duple or triple, and unfolded in phrases of similar lengths. As the century progressed, these melodies became increasingly difficult or virtuosic. If the purpose of the recitative was to convey emotions through a simple melodic line, then the purpose of the aria was increasingly to impress the audience with the skills of the singer.

Opera was initially commissioned by Italian noblemen, often for important occasions such as marriages or births, and performed in the halls of their castles and palaces. By the mid to late seventeenth century, opera had spread not only to the courts of France, Germany, and England, but also to the general public, with performances in public opera houses first in Italy and later elsewhere on the continent and in the British Isles. By the eighteenth century, opera would become almost as ubiquitous as movies are for us today. Most Baroque operas featured topics from the ancient world or mythology, in which humans struggled with fate and in which the heroic actions of nobles and mythological heroes were supplemented by the righteous judgments of the gods. Perhaps because of the cosmic reaches of its narratives, opera came to be called opera seria, or serious opera. Librettos, or the words of the opera, were to be of the highest literary quality and designed to be set to music. Italian remained the most common language of opera, and Italian opera was popular in England and Germany; the French were the first to perform operas in their native tongue.

Focus On Composition: “Tu se morta” (“You are dead”) from Monteverdi’s Orfeo (1607)

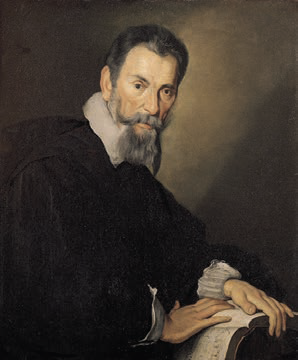

One of the very first operas was written by an Italian composer named Claudio Monteverdi (1567-1643). For many years, Monteverdi worked for the Duke of Mantua in central Italy. There, he wrote Orfeo (1607), an opera based on the mythological character of Orpheus from Ovid’s Metamorphoses. In many ways, Orpheus was an ideal character for early opera (and indeed many early opera composers set his story): he was a musician who could charm with the playing of his harp not only forest animals but also figures from the underworld, from the river keeper Charon to the god of the underworld Pluto. Orpheus’s story is a tragedy.

He and Eurydice have fallen in love and will be married. To celebrate, Eurydice and her female friends head to the countryside where she is bitten by a snake and dies. Grieving but determined, Orpheus travels to the underworld to bring her back to the land of the living. Pluto grants his permission on one condition: Orpheus shall lead Eurydice out of the underworld without looking back. He is not able to do this (different versions give various causes), and the two are separated for all eternity. One of the most famous recitatives of Monteverdi’s opera is sung by Orpheus after he has just learned of the death of his beloved Eurydice. The words of his recitative move from expressing astonishment that his beloved Eurydice is dead to expressing his determination to retrieve her from the underworld. He uses poetic images, referring to the stars and the great abyss, before, in the end, bidding farewell to the earth, the sky, and the sun, in preparation for his journey. As recitative, Orpheus’s musical line is flexible in its rhythms. Orpheus sings to the accompaniment of the basso continuo, here just a small organ and a long-necked Baroque lute called the theorbo, which follows his melodic line, pausing where he pauses and moving on where he does. Most of the chords played by the basso continuo are minor chords, emphasizing Orpheus’s sadness. There are also incidents of word painting, the depiction of specific images from the text by the music.

Whether you end up liking “Tu se morta” or not, we hope that you can hear it as dramatic, as attempting to convey as vividly as possible Orpheus’s deep sorrow. Not all the music of Orfeo is slow and sad like “Tu se morta.” In this recitative, the new Baroque emphasis on music as expressive of emotions, especially tragic emotions such as sorrow on the death of a loved one, is very clear.

Listening Guide: Tu se morta

Features Jordi Savall and Le Concert des Nations, La Capella Reial de Catalunya,

Furio Zanasi singing the role of Orfeo

- Composer: Claudio Monteverdi

- Composition: “Tu Se Morta” (“You are dead”) from Orfeo

- Date: 1607

- Genre: Recitative followed by a short chorus

- Form: Through-composed

- Nature of Text: Lyrics in Italian

- Performing Forces: solo vocalist and basso continuo (here organ and theorbo), followed by chorus accompanied by a small orchestra

What we want you to remember about this composition:

- It is one of the first operas.

- It is homophonic, accompanied by basso continuo

- It uses word painting to emphasize Orfeo’s sorrow

Other things to listen for:

- Its melodic line is mostly conjunct and the range is about an octave in range.

- Most of its chords are minor and there are some dissonances

- Its notated rhythms follow the rhythms of the text and are sung flexibly within a basic duple meter

- It is sung in Italian like much Baroque opera

|

|

|

|

Time |

Timing Performing Forces, Melody, and Texture |

Text and Form |

|

0:00 |

Solo vocalist and basso continuo in homophonic texture; Singer registers sadness and surprise through pauses and repetition of words such as “never to return” |

“Tu se morta, se morta mia vita, e io respiro” And I breathe, you have left me./ “se’ da me par tita per mai piu,”You have left me forevermore,/ “mai piu’ non tornare,” Never to return, |

|

0:52 |

“No, No” (declaration to rescue Eurydice) intensified by being sung to high notes; melody descends to its lowest pitch on the word “abyss” |

“ed io rimango-“ and I remain- / “no, no, che se i versi alcuna cosa ponno,” No, no, if my verses have any power,/ “n’andra sicuro a’ piu profondi abissi,” I will go confidently to the deepest abysses, |

|

1:11 |

Descending pitches accompanied by dissonant chords when referring to the king of the shadows; Melody ascends to high pitch for the word “stars” |

“e, intenerito il cor del re de l’ombre,” And, having melted the heart of the king of shadows,/ “meco trarotti a riverder le stelle,” Will bring you back to me to see the stars again, |

|

1:30 |

Melody descends for the word “death” |

“o se cia negherammi empio destino,” Or, if pitiless fate denies me this,/ “rimarro teco in compagnia di morta.” I will remain with you in the company of death. |

|

1:53 |

“Earth,” “sky,” and “sun” are set on ever higher pitches suggesting their experienced position from a human perspective |

“Addio terra, addio cielo, e sole, addio;” Farewell earth, farewell sky, and sun, farewell. |

|

2:28 |

Chorus & small orchestra responds; Mostly homophonic texture, with some polyphony; Dissonance on the word “cruel.” |

Oh cruel destiny, oh despicable stars, oh inexorable skies |

Media Attributions

- Claudio Monteverdi © Wikipedia is licensed under a Public Domain license