Chapter 23: Compositional Styles

As has been true of all periods, music of the last one-hundred and twenty-five or so years is related to past traditions, yet has developed modes of expression that are distinctly modern and depart from earlier practices. Works of art are always in some respect reflective of the time in which they were created and, conversely, shape our perception of the period in which they were produced. Some music readily speaks to us because we are in some way connected to its historical and cultural context, yet often the closer works of art are to us in time, the more alien and inaccessible they seem. This is not a new phenomenon. Artists have traditionally been visionaries, creators of new ways of experiencing and communicating that challenge our comprehension. Insight into the circumstances of a work’s genesis and what the composer set out to accomplish can help us listen with more sympathy and understanding.

In the early decades of the 20th century, many creative artists were reacting against the aesthetics and values of Romanticism. The composer Igor Stravinsky and the painter/sculptor Pablo Picasso are among the important figures whose works reflect their interest in tribal societies and the primitive, ritualistic dimension of the human psyche that was the subject of Freud’s research and writings.

One of the most radical departures from past music traditions was Arnold Schoenberg’s “method of composing with twelve tones” which rejected principles of a key center and the distinction between consonance and dissonance that had been the foundation of Western music for centuries. Because of the absence of a tonic, twelve-tone music is often called “atonal,” a term to which Schoenberg objected, or “serial” because the compositional technique involves the manipulation of a germinal series of pitches. Schoenberg’s theoretical writings and his serial works have had a great impact on subsequent generations of composers. While twelve-tone describes Schoenberg’s compositional procedure, his style is classified as expressionist. Expressionism was an early 20th-century movement that sought to reveal through art the irrational, subconscious reality and repressed primordial impulses postulated and analyzed in the writings of Freud.

Another important development during the early decades of the 20th century was the awakening of interest among American visual artists, novelists, poets, playwrights, choreographers, and composers in creating works that reflected a distinctly American, as opposed to a European, sensibility. In music, the renowned Czech composer Antonin Dvorak, who visited the United States during the 1890s, challenged Americans to compose their own music based on native folk materials. His own Symphony # 9 (1893), written during his stay in America, was evocative of the African-American spiritual.

By the 1920s American composers like George Gershwin and Aaron Copland were incorporating the rhythms and blues tonality of jazz into their symphonic works. Gershwin’s 1924 piece, Rhapsody in Blue, is the best-known work from this genre.

During the 1930s and early 1940s, Copland, Gershwin, Virgil Thomson, and Roy Harris drew from an array of American folk styles including spirituals, blues, cowboy songs, folk hymns, and fiddle tunes in composing their populist symphonic works.

Copland conducts his own Hoedown from Rodeo

American composers of the early 20th century also sought to create distinctly new works by engaging in radical experimentation. Charles Ives, writing in the first two decades of the century, was the first American to move away from the Romantic European conventions of form and style by employing dissonance, atonality, complex rhythms, and nonlinear structures. These ideas were continued by the American experimental composers Henry Cowell, Conlon Nancarrow, Edgar Varèse, and Ruth Crawford Seeger in the 1920s and 1930s. By the 1940s and into the post–World War II years, American avant-garde composer John Cage would challenge listeners to completely rethink what constituted music and art through his radically experimental works that drew from new technology, performance art, and Eastern systems of thought and aesthetics. Cage paved the way for the so-called “downtown” New York experimental scene that broke down barriers between music, visual art, performance, and so forth. Cage’s interest in non-Western music inspired the minimalist composers including Terry Riley, Steve Reich, and Philip Glass, who would draw on African and Asian musical systems in the 1960s and 1970s.

This interest in non-Western music in the last 75 years is a result of the unprecedented contact between different cultures. For most of human history, musical repertories have evolved largely in isolation from one another, so musical experiences have been principally confined to the music of an individual’s own immediate culture. Today the opportunities to hear music and the types of music that are available have expanded dramatically as a result of modern technology and increased contact among peoples. Modern modes of travel along with communication and technologies for recording music invented since the end of the 19th century have removed barriers that isolated different musical traditions and repertories from each other. People with access to the internet can listen to recordings covering the entire span of European classical music from the Middle Ages to the present, world music, folk music, and repertories that evolved during the 20th century such as jazz and rock. Music from distant times and places are also accessible through online music sites.

For musicians, the globalization of music has opened new doors and dissolved old boundaries. Performers study and gain mastery in repertoires of cultures other than their own, and composers can draw on literally the entire world of music in creating new crossover styles.

Modern technology has made possible not only the preservation and broad dissemination of music, but has also become a source for the generation and manipulation of musical sounds. One of the earliest devices that created musical sounds by electronic means, the Theremin (named after its inventor, the Russian scientist, Leon Theremin) was introduced in the early 1920s.

Using the numerous technologies that were developed in the following decades, composers recorded musical tones or natural sounds that they transformed by mechanical and electronic means and sometimes supplemented with others generated electronically in a studio. This raw material was then assembled for playback, either as a self-sufficient composition or combined with live performance.

Today, technology-based composition has become a widely available process through the storage of sound samples in computers. Synthesized, sampled, and digitally altered sounds are commonly used for special effects in popular music, movie scores, and works for the concert hall. There is also a repertory in which the tone color dimension of sound is what the work is about. Comparable to the abstract painter whose materials are the basic elements of shape and color, the composer constructs a succession of aural events of unique tone color, dynamics, and registration.

Compositional Styles: The “-isms”

Adapted from “The Twentieth Century and Beyond,”

Understanding Music: Past and Present

with additional content by Francis Scully

Edited and additional content by Jennifer Bill

Understanding Music: Past and Present is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-ShareAlike 4.0 International License.

Near the beginning of the twentieth century, numerous composers began to rebel against the excessive emotionalism of the later Romantic composers. Two different styles emerged: the Impressionist style led by Claude Debussy and Maurice Ravel, and the atonal Expressionist style led by Arnold Schoenberg. Both styles attempted to move away from the tonal harmonies, scales, and melodies of the previous period. The impressionists chose to use new chords, scales, and colors while the expressionists embraced dissonance.

Impressionism

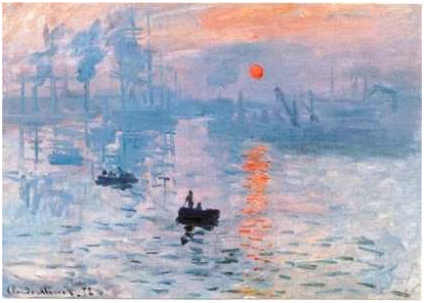

Impressionism is a term that originated in the visual arts. Impressionist paintings depict experiences, moods, and movement. In general, impressionist painters focused on using visual brush strokes to paint overall visual effects and capture light and its changing qualities rather than focusing on details.

Impressionism in music, as in art, focused on the creator’s impression of an object, concept, or event. In the painting Impression Sunrise, we see how the painter Claude Monet distilled a scene into its most basic elements. The attention to detail of previous centuries is abandoned in favor of broad brushstrokes that are meant to capture the momentary “impression” of the scene. To Monet, the objects in the scene, such as the trees and boats, are less important than the interplay between light and water. To further emphasize this interplay, Monet pares the color palate of the painting down to draw the focus to the sunlight and the water.

Similarly, Impressionist music does not attempt to follow a “program” like some Romantic compositions. It seeks, rather, to suggest an emotion or series of emotions or perceptions. The two major composers associated with the Impressionist movement are Claude Debussy and Maurice Ravel. Both French-born composers were searching for ways to break free from the rules of tonality that had evolved over the previous centuries. Listen to the example of Debussy’s La Mer (The Sea) linked below. Pay particular attention to the way the music seems to rise and fall like the waves in the sea and appears to progress without ever repeating a section. Music that is written this way is said to be “through-composed.” The majority of impressionist music is written in this manner. Even though such music refrains from following a specific program or story line, La Mer as music suggests a progression of events throughout the course of a day at sea. Note that Debussy retained the large orchestra first developed by Beethoven and used extensively by Romantic composers. This music is tonal and still uses more traditional scales and chords.

Impressionist composers also liked using sounds and rhythms that were unfamiliar to most Western European musicians. One of the most famous compositions by Maurice Ravel is entitled Bolero. A Bolero is a Spanish dance in three-four time, and it provided Ravel with a vehicle through which he could introduce different (and exotic, or different sounding) scales and rhythms into the European orchestral mainstream. This composition is also unique in that it was one of the first to use a relatively new family of instruments at the time: the saxophone family. Notice how the underlying rhythmic pattern repeats throughout the entire composition, and how the piece gradually builds in dynamic intensity to the end.

Listening Ravel Bolero

Characteristics of Impressionism

- Focused on Emotion, Mood, and Symbolism

- Impressionist music features the use of timbre to create “color” through harmonics, texture, orchestration, tempo, and rhythm.

- Lack of a tonal center

- Use of modes and “unusual” scales like pentatonic and whole-tone

- static harmony,

- emphasis on instrumental timbres that create a shimmering interplay of “colors”

- melodies that lack directed motion

- surface ornamentation that obscures or substitutes for melody

- avoidance of traditional musical forms.

Debussy

Claude Debussy (1862-1918) was a French composer widely regarded as one of the most influential figures of the early 20th century. He is best known for his innovative and evocative compositions that broke away from the traditional harmonic and structural norms of his time. Debussy’s music is often associated with the Impressionist movement in art, as he sought to create a sense of atmosphere and mood through his works, much like the Impressionist painters did with their brushstrokes.

In his early works, Debussy was influenced by composers like Wagner and Liszt, but later, he developed a unique style that departed from the grand Romantic traditions. His compositions often featured whole-tone scales, parallel chords, and pentatonic scales, which contributed to their distinctive and dreamlike quality. His innovative approach to composition opened new possibilities in music and paved the way for future generations of composers.

Debussy’s major works include:

- Clair de lune (“Moonlight,” in Suite bergamasque, 1890–1905)

- Prélude à l’après-midi d’un faune (1894; Prelude to the Afternoon of a Faun)

- the opera Pelléas et Mélisande (1902)

- La Mer (1905; “The Sea”)

Ravel

Maurice Ravel (1875-1937) was a French composer known for his exceptional craftsmanship and innovative approach to music. He is considered one of the leading figures of Impressionist and Neoclassical music. Ravel’s compositions are characterized by their meticulous attention to detail, colorful orchestration, and sophisticated harmonies. Ravel’s music often combined elements of Impressionism with a clear sense of form and structure, leading to a fusion of traditional and modern elements in his compositions.

Ravel was a master orchestrator, and his skill in crafting instrumental colors and textures is evident in his works. He was also a prolific composer in various genres, including piano music, chamber music, ballet, and songs. His piano compositions, such as “Gaspard de la nuit” and “Miroirs,” are considered some of the most challenging and expressive in the piano repertoire.

Throughout his career, Ravel enjoyed both critical and popular success. His music was admired for its elegance, emotional depth, and ability to create vivid imagery. He was a fastidious composer, often taking great care in revising and polishing his works, which contributed to their refined and polished nature.

Ravel’s major works include:

- Pavane pour une infante défunte (1899; Pavane for a Dead Princess)

- Rapsodie espagnole (1907)

- the ballet Daphnis et Chloé (first performed 1912)

- Le tombeau de Couperin (1917, the grave of Couperin)

- La Valse (1920)

- The opera L’Enfant et les sortilèges (1925; The Child and the Enchantments)

- Boléro (1928)

Expressionism

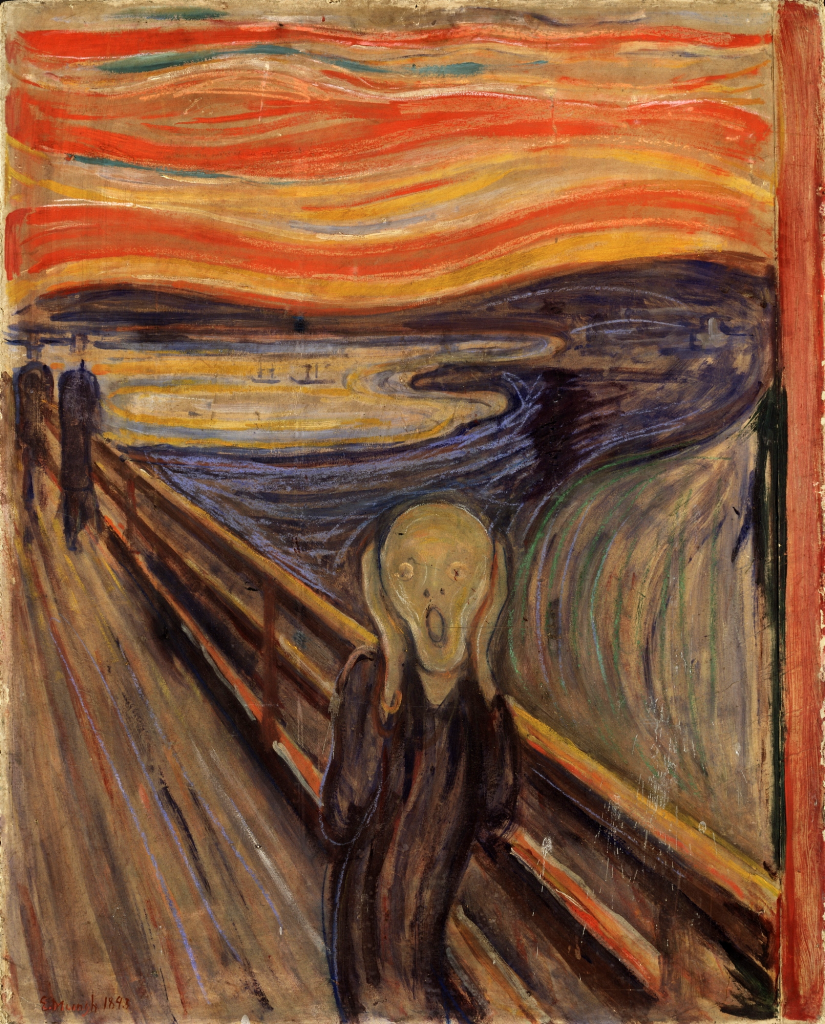

Expressionism, similar to impressionism, originally emerged in the realm of visual arts but later found its application in other art forms, including music. It arose as a counter to the delicate and momentary nature of impressionism. Rather than portraying hazy depictions of natural beauty, expressionism delves deep into the inner turmoil, anxiety, and apprehensions hidden within the subconscious mind. In the realm of music, expressionism fully embraces dissonance, showcasing its profound impact and emotional intensity.

In Edward Munch’s famous painting, The Scream, we see an excellent example of the parallel movement of expressionism taking place in the visual arts. Expressionists looked inward, specifically to the anxiety they felt toward the outside world. This was in stark contrast to the impressionists, who looked to the beauty of nature for inspiration. Expressionist paintings relied instead on stark colors and harsh swirling brushstrokes to convey the artist’s reaction to the ugliness of the modern world.

The Expressionist period in music was not a time when composers sought to express themselves emotionally in a romantic, beautiful, or programmatic way. Expressionism seems more appropriate for evoking more extreme, and sometimes even harsh, emotions. Theodor Adorno describes expressionism as concerned with the unconscious, and states that “the depiction of fear lies at the centre” of expressionist music, with dissonance predominating, so that the “harmonious, affirmative element of art is banished.”

Many of the early works of Austrian-born Arnold Schoenberg (1874-1951) exemplified an expressionistic musical style. Although he is most famous for his experiments with atonality, that is music without a tonal center, his early compositions were highly dissonant and sounded quite radical when compared to the music of the 19th century, which utilized dissonance only as a means to eventually return to the stasis of consonance. However, Schoenberg saw dissonance not as a means to an end, but as the end itself. His music invited the listener to revel in various levels of dissonance.

- Erwartung (1909) a one-act monodrama by Arnold Schoenberg

- Die Glückliche Hand (1913) an opera by Arnold Schoenberg

- Three Japanese Lyrics (1913) for voice and piano by Igor Stravinsky

- Wozzeck (1922) an opera by Alban Berg

- The Young Maiden (1922) a song cycle by Paul Hindemith

- Symphony No. 2 (1922) by Ernst Krenek

A-Tonality and Serialism

Atonality is a revolutionary concept that emerged in the late 19th and early 20th centuries as a reaction against the traditional tonal system that had dominated Western music for centuries. Unlike traditional tonal music, where compositions are centered around a specific key and follow established harmonic rules, atonal music abandons the concept of a central key and seeks to liberate composers from traditional harmonic constraints. In atonal music, there is no clear sense of a tonal center or hierarchy among pitches, and dissonance is embraced as a fundamental element of the musical language.

In 1909, Arnold Schoenberg composed the first complete work that completely did away with tonality. This piano composition was one of three that together are listed as his Opus 11 and was the first piece we now refer to as being completely atonal (without tonality). Schoenberg’s most-important atonal compositions include: Five Orchestral Pieces (1909), Pierrot Lunaire (1912), Die Jakobsleiter (Jacob’s Ladder – begun in 1917 but never finished), Die glückliche Hand (The Lucky Hand – 1924), and Erwartung (Expectation – 1924) for soprano and orchestra.

The term “atonality” was first coined by Joseph Marx in 1910 and later popularized by Arnold Schoenberg, Alban Berg, and Anton Webern, who are considered pioneers of atonal music. The most notable example of atonal music is Schoenberg’s composition “Pierrot Lunaire” (1912).

Schoenberg’s song cycle Pierrot Lunaire for solo soprano and five instrumentalists is one of the most famous examples of the expressionist and atonal style. The piece sets 21 poems by the Belgian symbolist Albert Guiraud. Pierrot, the “sad clown,” is a stock character from the Italian street theater tradition known as Commedia dell’arte. Guiraud’s poems, full of suggestive dream and nightmare imagery, present the adventures of Pierrot as he wanders about obsessed with the moon (“lunaire”), unlucky in love, and feeling alienated from society (perhaps Pierrot also represents the figure of the artist in the twentieth century who was perpetually misunderstood).

For this song cycle, Schoenberg invents a style of singing called Sprechstimme, a kind of half-singing, half-speaking where the singer only approximates singing exact pitches. The result is a highly theatrical singing style that effectively captures the extreme psychological states.

No. 1 “Moondrunk”: In this song, Schoenberg represents the moonlight with a dissonant descending melody on the piano. You’ll hear this repeated throughout the piece and shared with other instruments.

“Moondrunk” translation:

The wine which through our eyes we drink

Pours from the moon in waves upon us

And like a springtide

Overflows the stillness of the night.

Desires so thrilling and so sweet,

Cascading through the floods in thousands:

The wine which through our eyes we drink,

Pours from the moon in waves upon us.

The writer, so divinely moved,

Is greedy for the holy liquid,

And skyward he directs his dizzy head,

Then reeling, gulps and slurps down

The wine which through our eyes we drink.

Time: 50 sec

No. 8 “Night”: In this song, you hear the low instruments (cello, bass clarinet, and piano) depict the black moths of the poem. You will hear a three-note theme that is repeated again and again throughout the piece as Pierrot is overwhelmed with the arrival of night.

“Night” translation

Obscure, black giant moths

Killed the sun’s splendor.

A closed book of spells,

The horizon settles–hushed

From the mists of lost depths

Wafts a scent–remembrance murdered!

Obscure, black giant moths

Killed the sun’s splendor.

And from the sky earthwards

Sinking on heavy wings

Unseeable the monsters (glide)

Down into the human . . .

Obscure, black giant moths.

Time: 13:15

Part of what creates this expressionistic atmosphere in Pierrot Lunaire is that the music consciously avoids any sense of a tonal center. In later works, Schoenberg built upon this “atonal” style and developed a system whereby the twelve notes of the chromatic scale were organized into units that he called the twelve-tone row. These rows could then be further “serialized” (organized in a random fashion) by a number of different techniques. This idea of assigning values to musical information is called serialism. In 1921 Schoenberg composed his Piano Suite, opus 25, the first composition written using the 12-tone method. Each 12-tone composition is built from a series of 12 different pitches that may be arranged in a number of different ways. The original row may be played forward, backward (retrograde), upside down (inverted), and backward and inverted (retrograde inversion). All of the melodies and harmonies in a 12-tone piece must be derived in some way from the original row or from fragments of the original row.

In 1925 Schoenberg was hired by the Prussian Academy of Arts in Berlin to teach composition, and he would most likely have continued his career as a teacher and composer in Europe were it not for the rise of the Nazi party and their subsequent persecution of European Jews. In 1933 he was released from the Academy and moved first to Paris and then to Boston. In 1934 he settled in California and held teaching positions first at the University of Southern California (1935-36) and then the University of Central Los Angeles (1936-44).

After immigrating to the United States, Schoenberg reconnected with the Jewish faith he had abandoned as a young man. The sadness he felt because of the personal accounts of the horrendous treatment experienced by so many Jews during World War II led to his composition of A Survivor from Warsaw, which was composed for orchestra, male chorus, and narrator. The piece was completed in September 1947 and the entire piece is built on a twelve-tone row. This important work is Schoenberg’s dramatization of a tragic story he heard from surviving Polish Jews who were victims of Nazi atrocities during World War II. Schoenberg created a story about a number of Jews who survived the war by living in the sewers of Warsaw. Interestingly, among Schoenberg’s many and very specific performance instructions is the request that the narrator does not attempt to sing his part throughout the performance.

Schoenberg’s ideas were further developed by his two famous students, Alban Berg, and Anton Webern. Together, the three came to be known as the Second Viennese School, in reference to the first Viennese School, which consisted of Hadyn, Mozart, and Beethoven. Born in Vienna,

Alban Berg began studying with Schoenberg at the age of 19 and soon became known for his unique compositional style, which fused post-romantic concepts with Schoenberg’s cutting-edge twelve-tone techniques. Heavily influenced by Richard Wagner, Berg held on to techniques such as the leitmotif and sought to couch his harmonic ideas in tried-and-true forms such as the sonata and fugue. Although he composed many famous pieces, such as his Violin Concerto and his unfinished opera Lulu, he initially made his fame with Wozzeck, an opera based on the drama Woyzeck by German playwright Georg Buchner. Berg served during World War I, and much of Wozzeck was composed in 1917, during a period of leave from the Austro-Hungarian Army. The opera consists of three acts, each with five scenes organized around the variations of a musical idea, such as the variations of a theme, a chord, or a rhythmic pattern. Berg himself adapted the libretto from Buchner’s original play.

The story of the opera centers on the title character Wozzeck. Like the main character in many romantic operas, he is a tragic figure. However, whereas the operas of the nineteenth century often depicted gods and mythical figures, the story of Wozzeck is couched in a sense of realism and addresses the type of societal problems that Berg may himself have encountered during World War I, problems such as apathy and human cruelty. The character of Wozzeck is that of a pitiful and unremarkable soldier who is tormented by his captain and used for and subjected to medical experiments by a sadistic doctor. Wozzeck, who is often given to hallucinations, eventually goes mad and kills his love interest, Marie, who has been unfaithful. The opera ends after Wozzeck drowns trying to clean the murder weapon in a pond and wading out too far.

Listen to the recording below of act 3, scene 2, the scene in which Wozzeck kills Marie. The scene features a variation on a single note, namely B.

Time: 8:30

Total Serialism

Total serialism is an extension and refinement of the twelve-tone technique, a form of serialism that aims to apply serial principles not only to pitch but also to other musical elements, including rhythm, dynamics, and articulation. It emerged in the mid-20th century as a natural progression of the serialist movement in music.

In total serialism, the composer organizes not only the twelve pitches of the chromatic scale but also other aspects of the music’s structure using predetermined series or rows. These rows dictate the order in which pitches, rhythms, dynamics, and other elements appear in the composition.

By systematically controlling all musical parameters through serial principles, total serialism seeks to create a cohesive and tightly structured musical work. Composers using total serialism often strive for a high degree of control and mathematical rigor in their compositions, resulting in intricate and complex musical textures.

The Austrian composer Anton Webern was an early proponent of total serialism, and his works often serve as prime examples of the technique. Other notable composers who explored total serialism include Pierre Boulez, Karlheinz Stockhausen, and Milton Babbitt.

Examples of Total Serialism

- Anton Webern Sechs Bagatellen, op.9 (string quartet)

- Milton Babbitt three compositions for piano

- Milton Babbitt composition for twelve instruments

- Ruth Crawford Seeger Nine Preludes (solo piano)

- Pierre Boulez Le marteau sans maître (contralto and ensemble)

- Pierre Boulez Structures (for 2 pianos)

- Karlheinz Stockhausen Kontra-Punkte

Primitivism

Primitivism in music is a movement that emerged in the early 20th century, influenced by the broader primitivist movement in the arts. It sought to evoke the perceived simplicity, rawness, and vitality of so-called “primitive” cultures, particularly those from non-Western and indigenous societies. As a genre of Western art, Primitivism reproduced and perpetuated racist stereotypes with which colonialists justified white colonial rule over the non-white “other” in Asia, Africa, and Australasia.

Composers who embraced primitivism sought to break away from the constraints of Western classical traditions and explore more elemental and primal aspects of music. They drew inspiration from folk music, ancient rituals, and non-European musical traditions, as well as the art of tribal societies and ancient civilizations. Primitivism in music often involved the incorporation of percussive and rhythmic elements, irregular meters, and unconventional instrumental techniques to create a sense of primitiveness and raw power.

The brilliant Igor Stravinsky (1882-1971) was a cosmopolitan figure, having lived and composed in Russia, France, Switzerland, and the United States. His music influenced numerous composers, including the famed French composition teacher Nadia Boulanger. Stravinsky caused quite a stir when his ballet entitled The Rite of Spring premiered in Paris in 1913. The ballet was choreographed by Vaslav Nijinsky, and the music and dance were so new and different that it nearly caused a riot in the audience. The orchestral version has become one of the most admired compositions of the twentieth century.

Stravinsky’s The Rite of Spring is primitivist program music about the subject of Paganism, specifically the rite of human sacrifice in pre-christian Russia. Its rhythmic complexity, dissonant harmonies, and use of unconventional scales were seen as a radical departure from traditional European classical music, leading to one of the most notorious premieres in musical history.

Stravinsky’s use of “primitive” sounding rhythms to depict several pagan ritual scenes makes the term “primitivism” seem appropriate.

Neoclassism

In the decades between World War I and World War II, many composers in the Western world began to write in a style we now call Neoclassicism. When composing in a neoclassic manner, composers attempted to infuse many of the characteristics of the classical period into their music, incorporating concepts like balance (of form and phrase), economy of material, emotional restraint, and clarity in design. They also returned to popular classical forms like the Fugue, the Concerto Grosso, and the Symphony. But these pieces are not simply imitations of an older style. They continue to push musical boundaries through dissonance and modernist harmonies along with experimental approaches to rhythm and meter. For artists and composers traumatized by the devastation of World War I, neoclassicism was attractive for its anti-Romantic avoidance of emotionalism.

A neo-classicist composer is inclined to incorporate elements of extended tonality, modality, or even atonality instead of adhering to the hierarchical tonal system characteristic of true (Viennese) Classicism. As a result, the prefix “neo-” frequently suggests a sense of parody or distortion of the genuine Classical traits.

Numerous well-known composers incorporated neoclassic techniques and philosophy into their compositions. Stravinsky was among them, and his ballet entitled Pulcinella (1920) is an early example of the neoclassical style. It was based on music that Stravinsky originally thought was written by the Baroque composer Giovanni Pergolesi. Music historians later deduced that the compositions were written by Pergolesi’s contemporaries and not by Pergolesi himself. Stravinsky borrowed specific themes from these earlier works and combined them with more modern harmonies and rhythms. Listen to how in some sections the music closely approximates the style and sounds of Baroque composers, while in other sections it sounds much more aggressive, primitive, and modern.

One composer who was able to combine elements of neo-Classicism with the traditions of his homeland was Béla Bartók (1881 – 1945). Bartok was born in Nagyszentmiklós, Hungary, and was an important figure in the music of the early twentieth century. A noted composer, teacher, pianist, and ethnomusicologist, he was appointed to a position in the Royal Academy of Music in Budapest in 1907 and worked there until 1934. Along with his friend and colleague Zoltán Kodály, Bartók enthusiastically researched and sought out the traditional music of the Hungarian people, and both composers analyzed and transcribed the music they collected, as well as using this folk music as inspiration for their own original compositions.

In addition to Hungarian folk music, Bartók’s style was also influenced by the Romantic music of Strauss and the Hungarian composer Franz Liszt. He was also influenced by Debussy’s impressionism and the more modern music of Igor Stravinsky and Arnold Schoenberg. As a result of all of these influences, his music was often quite rhythmic, and it incorporated both tonal and chromatic (moving by half-steps) elements. Bartók composed numerous piano works, six string quartets, and an opera titled Duke Bluebeard’s Castle, as well as a ballet entitled The Wooden Prince (1916), and a pantomime entitled The Miraculous Mandarin (1919). His string quartets and his Concerto for Orchestra have become part of the standard repertoire of professional performing groups around the world.

Other important neoclassical works include Stravinsky’s Symphony of Psalms (1930), Dumbarton Oaks (1937), and Apollo (1928), Sergei Prokofiev’s Symphony No. 1 (1918) and Violin Concerto No. 2 (1935), and Maurice Ravel’s Piano Concerto in G (1931) and Le Tombeau de Couperin (1917).

Minimalism

Minimal music, also known as minimalism, is a style of composition that utilizes a restricted and simplistic set of musical elements. Key characteristics of minimalist music encompass repetitive patterns or rhythmic pulses, continuous drones, consonant harmonies, and the repetition of musical phrases or smaller units.

Minimalism is a movement that began in New York during the 1960s, and it stands in stark contrast to much of the music of the early twentieth century. Minimalist composers sought to distill music down to its fundamental elements. Minimalist pieces were highly consonant and often relied on the familiar sounds of triads. Instead of featuring rhythmic complexity, minimalist composers established a steady meter. And, unlike twelve-tone music, which avoided repetition at all costs, minimalist composers made repetition the very focus of their music. Change was introduced very slowly through small variations of repeated patterns, and, in many cases, these changes were almost invisible to the listener. Arguably the most famous two composers of the minimalistic style were Stephen Reich (b.1936) and Philip Glass (b.1937).

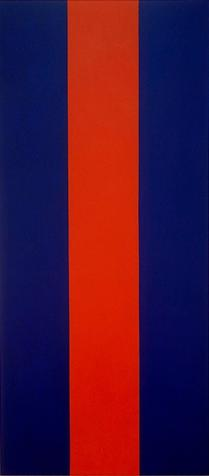

But minimalism wasn’t confined to the realm of music. In Barnett Newman’s (1905-1970) painting Voice of Fire (1967), we see that many of these same concepts of simplification applied to the visual arts. Minimalist painters such as Newman created starkly simple artwork consisting of basic shapes, straight lines, and primary colors. This was a departure from the abstract expressionists such as Jackson Pollack in the same way that Steve Reich’s compositions were a departure from the complexity of Arnold Schoenberg’s music.

Steve Reich’s Music for 18 Musicians is a composition featuring eleven related sections performed by an ensemble consisting of mallet instruments, women’s voices, woodwinds, and percussion. Section VII is constructed of a steady six-beat rhythmic pattern that is established at the beginning of the piece. Over this unfaltering rhythmic pattern, various instruments enter with their own repeated melodic motifs. The only real changes in the piece take place in very slow variations of rhythmic density, overall texture, and instrumental range. All of the melodic patterns in the piece fit neatly into a simple three-chord pattern, which is also repeated throughout the piece. Many minimalistic pieces follow this template of slow variations over a simple pattern. This repetition results in music with a hypnotic quality, but also with just enough change to hold the listener’s interest.

- La Monte Young’s Trio for Strings (1958) and The Well-Tuned Piano (1964)

- experiment with droning textures and slow harmonic progressions.

- experiment with droning textures and slow harmonic progressions.

- Terry Riley’s In C (1960)

- would serve as a template for the possibilities of minimalist music.

- would serve as a template for the possibilities of minimalist music.

- Steve Reich’s Music For 18 Musicians, Different Trains, and Four Organs.

- Philip Glass’ Einstein on the Beach, Metamorphosis, and Koyaanisqatsi

The American Style

Jazz is a uniquely American form of music, and American orchestral composers were commonly influenced by jazz in the early twentieth century, and George Gershwin (1898-1937) was no exception. Gershwin was a brilliant talent who dropped out of school at the age of fifteen to begin a professional career playing piano in New York’s “Tin Pan Alley.” After several years of success as a performer and composer, he was asked by the famous band leader Paul Whiteman to compose a work that would help raise people’s perceptions of jazz as an art form. The resulting work, Rhapsody in Blue, combines the American jazz style with the European symphonic tradition into a brilliant composition for piano and orchestra. Listen to how beautifully Gershwin combines these elements.

In addition to Rhapsody in Blue, George Gershwin is famously known for his opera, “Porgy and Bess.” Although Gershwin dubbed it a “folk opera”, the piece is considered one of the great American operatic works of the century. The story is set in a tenement in Charleston, South Carolina. Based on DuBose Heyward’s novel Porgy, the opera incorporated classically trained black singers to depict the tragic love story between the two main title characters. Gershwin based the music for the opera on elements of southern black musical styles such as the blues and spirituals. Drawing on the nineteenth-century opera tradition, Gershwin made use of leitmotifs to represent people or places. Near the beginning of the opera, we hear the famous aria “Summertime,” which depicts the hot, hazy atmosphere in which the story is set.

Like Gershwin, American-born Aaron Copland (1900-1990) was instrumental in helping to define a distinctly American sound by combining his European musical training with jazz and folk elements. As an early twentieth-century composer, Copland was active during the Great Depression, writing music for the new genre of radio, the phonograph, and motion pictures. El Salon Mexico (1935), Fanfare for the Common Man (1942), and Appalachian Spring (1944) are three of Copland’s most famous works. He won a Pulitzer Prize for his music for the ballet Appalachian Spring and was also an Oscar-winning film composer. Appalachian Spring is a ballet depicting a pioneer wedding celebration in a newly-built farmhouse in Pennsylvania. It includes the now well-known Shaker song “Simple Gifts”.

Copland’s unique style evokes images of the landscape of the western United States, as we can hear in his score for the ballet Rodeo (1942).

One of the ways in which Copland was able to capture the sense of the vastness of the American landscape was through his use of certain harmonic intervals, that is, two notes played together, which sound “hollow” or “open.” These intervals, which are called “perfect 4ths” and “perfect 5ths,” have been used since medieval times, and were named so due to their simple harmonic ratios. The result is music that sounds vast and expansive. Perhaps the best example of this technique is found in Copland’s famous Fanfare for the Common Man.

While fanfares are typically associated with heralding the arrival of royalty, Copland wanted to create a fanfare that celebrated the lives of everyday people during a trying time in American history. The piece was premiered by the Cincinnati Symphony Orchestra on March 12, 1943, at the height of World War II. It has been used in countless movies, television shows, and even military recruitment ads. The piece came to define Copland’s uniquely American compositional style and remains one of the most popular patriotic pieces in the American repertoire.

Electronic Music

Modern electronic inventions continue to change and shape our lives. Music has not been immune to these changes. Computers, synthesizers, and massive sound systems have become common throughout the Western world.

Electro-acoustic music refers to a genre that harnesses electronic technology, predominantly computer-based, to access, generate, explore, and manipulate sound materials. This art form relies on loudspeakers as the primary medium of transmission, allowing for the creation of immersive and innovative sonic experiences.

Two main genres have developed in electro-acoustic music

- Acousmatic music is intended for loudspeaker listening and exists only in recorded form (tape, compact disc, computer storage, etc.).

- In live electronic music, the technology is used to generate, transform or trigger sounds (or a combination of these) in the act of performance; this may include generating sound with voices and traditional instruments, electro-acoustic instruments, or other devices and controls linked to computer-based systems.

Both genres depend on loudspeaker transmission, and an electro-acoustic work can combine acousmatic and live elements.

Musique Concrète

Musique concrète (a French term meaning “concrete music”) is a type of electro-acoustic music that uses both electronically produced sounds (like synthesizers) and recorded natural sounds (like instruments, voices, and sounds from nature). Musique concrète utilizes recorded sounds as raw material. Sounds are often modified through the application of audio signal processing and tape music techniques, and may be assembled into a form of sound collage. The technique exploits acousmatic sound, such that sound identities can often be intentionally obscured or appear unconnected to their original source.

Pierre Schaeffer (in the 1940s) was a leader in developing this technique. Unlike traditional composers, composers of musique concrète are not restricted to using rhythm, melody, harmony, instrumentation, form, and other musical elements. The video linked below offers an excellent narrative on musique concrète.

Musique concrète

Below is a link to one of Pierre Schaeffer’s musique concrète compositions.

Pierre Schaeffer, Études de bruits (1948)

Elektronische Musik

Elektronische Musik (German term meaning “electronic music”) is composed by manipulating only electronically-produced sounds rather than recorded sounds. Karlheinz Stockhausen was a leader in the creation of elektronische Musik.

By the early 1950s musique concrète was contrasted with “pure” elektronische Musik but the distinction has since been blurred such that the term electronic music covers both meanings.

- Pierre Schaeffer and Pierre Henry Symphonie pour un homme seul (Symphony for One Man Only)

- Edgard Varèse Déserts (for tape and instruments)

- Edgard Varèse Poème électronique (performed by 400 loudspeakers at the 1958 Brussels World’s Fair)

- Karlheinz Stockhausen Gesange der Jünglinge

Laptop Orchestras

With the development of laptop computers, a new wave of interest has sprung up world-wide in electronic music of all types. Musicians can now easily link laptops together to form ensembles; they can also link laptops in other locations, even around the globe. Software is being developed that allows for all types of musique concrète and elektronische musik compositions and combinations. The Princeton Laptop Orchestra is a leader in this area of experimental composition and performance.

Princeton Laptop Orchestra

Chance Music

Chance music (also aleatory music or aleatoric music or indeterminate music) is music in which some element of the composition is left to chance, and/or some primary element of a composed work’s realization is left to the determination of its performer(s). Chance music is a genre that embraces the role of chance and randomness in the creation of music, leading to compositions that are more open-ended and exploratory in nature. It challenges traditional notions of composer control and invites both composers and performers to engage with the music in a more spontaneous and creative manner.

Chance Music can be divided into three groups:

The first group uses random procedures to produce a determinate, fixed score.

The chance element is involved only in the process of composition, so that every parameter is fixed before their performance.

Examples:

John Cage’s Music of Changes (1951), the composer selected duration, tempo, and dynamics by using the I Ching, an ancient Chinese book which prescribes methods for arriving at random numbers. Because this work is absolutely fixed from performance to performance, Cage regarded it as an entirely determinate work made using chance procedures.

Iannis Xenakis used probability theories to define some microscopic aspects of Pithoprakta (1955–56), which is Greek for “actions by means of probability”. This work contains four sections, characterized by textural and timbral attributes, such as glissandi and pizzicati. At the macroscopic level, the sections are designed and controlled by the composer while the single components of sound are controlled by mathematical theories.

In the second type of indeterminate music, chance elements involve the performance. Notated events are provided by the composer, but their arrangement is left to the determination of the performer.

Examples:

Henry Cowell’s the Mosaic Quartet (String Quartet No. 3, 1934), allows the players to arrange the fragments of music in a number of different possible sequences. Cowell also used specially devised notations to introduce variability into the performance of a work, sometimes instructing the performers to improvise a short passage or play ad libitum.

Alan Hovhaness (beginning with his Lousadzak of 1944) used procedures in which different short patterns with specified pitches and rhythm are assigned to several parts, with instructions that they be performed repeatedly at their own speed without coordination with the rest of the ensemble.

Karlheinz Stockhausen’s Klavierstück XI (1956) presents nineteen events which are composed and notated in a traditional way, but the arrangement of these events is determined by the performer spontaneously during the performance.

The greatest degree of chance is reached by the third type of indeterminate music, where traditional musical notation is replaced by visual or verbal signs suggesting how a work can be performed, for example in graphic score pieces.

Examples:

Earle Brown’s December 1952 (1952) shows lines and rectangles of various lengths and thicknesses that can read as loudness, duration, or pitch. The performer chooses how to read them.

Morton Feldman’s Intersection No. 2 (1951) for piano solo, is written on coordinate paper. Time units are represented by the squares viewed horizontally, while relative pitch levels of high, middle, and low are indicated by three vertical squares in each row. The performer determines what particular pitches and rhythms to play.

Postmodernism

As we’ve observed, composers throughout the twentieth century brought a sense of experimentation to musical composition and the search for new languages of art and music resulted in some wildly musical sounds.

But where do you go, once it seems as if all the radical experiments have been conducted? For many composers of the late-twentieth century, the end of modernism brought the opportunity to freely pick and choose from various styles. A composer might incorporate twentieth-century modernist styles, Romantic era sounds, classical style, baroque style and bring in elements of popular music, global music, and jazz.

John Adams (b. 1947) is probably the most well-known American composer living today. His early music was written in a minimalist style, but he has embraced 12-tone style, pop music styles, and opera, and often writes for a large, Romantic-sized orchestra.

Nowadays, classical music is a global phenomenon. Composers from all over the world are writing operas, symphonies, concertos, string quartets, etc. There are composers writing exciting classical music in Africa, the Middle East, South America, all over. The 2000 film Crouching Tiger, Hidden Dragon (directed by Ang Lee) was an enormously popular film that won an academy award for Best Original Score. The music for the film includes a cello concerto written by the Chinese composer Tan Dun (b. 1957), which incorporates traditional Chinese music styles with the Western classical tradition.

Osvaldo Golijov (b. 1960) is another composer who represents the global trend in contemporary classical music. Golijov is an Argentine of Israeli descent and his music reflects the influences of Jewish culture, South American culture, as well as contemporary popular music.

Listen to these excerpts from La Pasión según San Marcos:

Twenty-first century classical music is also no longer dominated by male composers and there are many fascinating female composers who are making their mark in concert halls all over the world. A few names of prominent composers today include: Kaija Saariaho, Sofia Gubaidulina, Jennifer Higdon, Chen Yi, Julia Wolfe, Gabriela Lena Frank, Missy Mazzoli, Unsuk Chin, Tania Leon, Anna Clyne, and Joan Tower.

In fact, the winner of the 2012 Pulitzer Prize winner in music (the highest honor for a composer in the United States) was a young female composer named Caroline Shaw (b. 1982).

At 30 years old, she was the youngest-ever recipient of the award. Take a listen to the first movement of her piece Partita for 8 Voices (2012).

Roomful of Teeth – Shaw: Allemande (1st movement) from Partita for 8 Voices

GLOSSARY

- Atonal – Music that seeks to avoid both the traditional rules of harmony and the use of chords or scales that provide a tonal center

- Chromaticism – a style of composition which uses notes that are not a part of the predominant scale of a composition or one of its sections.

- Elektronische Musik – (German term meaning “electronic music”) Music composed by manipulating only electronically-produced sounds (not recorded sounds.)

- Expressionism – Style of composition where composers intentionally use atonality. Arnold Schoenberg devised a system of composing using twelve tones. His students Alban Berg and Anton Webern composed extensively in this twelve-tone style.

- Impressionism – music composed based on the composer’s impression of an object, concept, or event. This style included the use of chromaticism, whole-tone scales and chords, exotic scales, new chord progressions, and more complex rhythms

- Laptop orchestra – an ensemble formed by linking laptop computers and speakers together to generate live and/or recorded performances using both synthesized and pre-recorded sounds

- Musique Concrète – a type of electro-acoustic music that uses both electronically produced sounds (like synthesizers) and recorded natural sounds (like instruments, voices, and sounds from nature)

- Neoclassicism – A musical movement that arose in the twentieth century as a reaction against romanticism and which sought to recapture classical ideals like symmetry, order, and restraint. Stravinsky’s music for the ballet Pulcinella (1920) is a major early neoclassical composition.

- Polytonality – a compositional technique where two or more instruments or voices in different keys (tonal centers) perform together at the same time

- Primitivism – A musical movement that arose as a reaction against musical impressionism and which focused on the use of strong rhythmic pulse, distinct musical ideas, and a tonality based on one central tone as a unifying factor instead of a central key or chord progression.

- Serialism – composing music using a series of values assigned to musical elements such as pitch, duration, dynamics, and instrumentation. Arnold Schoenberg’s 12-tone technique is one of the most important examples of serialism.

- Synthesizers – instruments that electronically generate a wide variety of sounds. They can also modify electronic or naturally produced recorded sounds

- Through-Composed – Music that progresses without ever repeating a section

- Twelve-tone Technique – Compositional technique developed by Arnold Schoenberg that derives musical elements such as pitch, duration, dynamics, and instrumentation from a randomly produced series of the twelve tones of the chromatic scale (the 12-tone row)

Licensing & Attributions

Adapted from “European and American Art Music since 1900” from Music: Its Language, History, and Culture

Douglas Cohen – CUNY Brooklyn College

Edited and additional content by Jennifer Bill

Music: Its Language, History, and Culture by the Conservatory of Music at Brooklyn College of the City University of New York is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-ShareAlike 4.0 International License.

Based on a work at http://www.music1300.info/reader

Permissions beyond the scope of this license may be available at http://www.music1300.info/reader.

Media Attributions

- Soleil levant © Wikipedia is licensed under a Public Domain license

- Skrik by Edvard Munch © Wikipedia is licensed under a Public Domain license

- Voice of Fire (1967) © Japs 88 via. Wikipedia is licensed under a All Rights Reserved license