Chapter 22: Modern Music of the 20th and 21st Centuries

Introduction

What makes music “modern?” This section proposes that heightened ambiguity differentiates experimental twentieth-century music from the common-practice era repertoire.

In this section, we will study the ways in which progressive modern music differs from common-practice era or otherwise known as “classical” music. We will then use the conceptual and listening tools that we have developed in earlier units as an entryway into the modern repertoire.

To truly understand music in the 20th and 21st centuries it is important to have knowledge of historical events, scientific developments, technological developments, and parallel art movements. Supplemental materials on these topics are available and are highly recommended for the reader to explore.

What to Expect When Listening to Modern Music

Heightening Musical Ambiguity

Because it is non-verbal and often non-representational, music is particularly ambiguous. And yet, as the following will make clear, classical composers put a high value on clarity and resolution. Progressive twentieth-century composers shifted the balance much more strongly towards the uncertain and the unresolved.

Individualized Musical Languages

Within European art music, the common-practice era denotes the age of tonality, encompassing consistent characteristics from the mid-Baroque era through the Classical and Romantic periods, spanning approximately from 1650 to 1900. Throughout these centuries, there was substantial stylistic evolution, witnessing the rise and fall of patterns and conventions like standardized harmonic functions, consistent metric structures, and structural forms such as binary form and the sonata form. The prevailing and cohesive element that prevailed throughout this period was tonal harmonic language.

The shared materials and formal methods of the common-practice era helped to make the music more accessible to audiences. In past units, listening to one common practice era work helped you understand how to listen to others from the same time period.

For example, the following excerpts by Franz Schubert and Johannes Brahms were written seventy years apart, but if Schubert had been alive to hear Brahms’ work, the music would no doubt have been intelligible to him.

Franz Schubert: Sonata in A-Major, D. 664 (1819)

Time: 0 – 0:55

Johannes Brahms: Intermezzo in A-Major, Opus 118 (1893)

Time: 0 – 1:20

During the twentieth century, the common practice era came to an end. Composers intensified the individuality of their musical voices. The following works for similar instrumentation were composed within several years of each other:

Igor Stravinsky: The Soldier’s March from L’Histoire du Soldat (1918)

Time: 0 – 2:15

Arnold Schonberg: Mondestrunken from Pierrot Lunaire (1912)

Time: 0:55 – 2:37

A few decades later, the following string quartets were written very close together.

Elliot Carter: String Quartet No.1, II (1951)

John Cage: String Quartet in 4 parts, IV (1950)

Finally, the following works for two pianos were written within six years of each other.

Steve Reich: Piano Phase

Time: 0 – 2:50 (1967)

Pierre Boulez: Structures II for Two Pianos, Chapter 2 (1961)

Time: 0 – 2:02

Even though these paired pieces share the same instrumentation and were written around the same time, they do not share the same musical language. Listening to one piece does not help teach you how to listen to the other. Each work and composer must be considered on their own terms.

The personality of individual musical languages was established in a multitude of ways. Some composers, such as Harry Partch, invented their own instruments. (Partch gave his instruments such fanciful names such as Cloud-Chamber Bowls, Diamond Marimba, and Chromolodeon.)

Explanations of Partch instruments

Time: 2:45 – 3:50 and 7:50 – 9:40

Harry Partch: Castor & Pollux

Time: 0 – 1:20

Some, like Pierre Schaeffer, Pierre Henry, and Mario Davidovsky, pioneered the use of electronic sounds.

Schaeffer and Henry’s Symphonie pour un homme seul (1950) laid the technical foundations for tape music.

In Davidovsky’s Synchronism No.9 (1988), live and recorded electronically transformed violin sounds are intertwined. Davidovsky explains that, “One of the central ideas of these pieces is the search to find ways of embedding both the acoustic and the electronic into a single, coherent musical and aesthetic space.”

Grimshaw, Jeremy (2005). “Mario Davidovsky”, All Music Guide to Classical Music: The Definitive Guide to Classical Music, p.341-2. Woodstra, Chris; Brennan, Gerald; and Schrott, Allen; eds.

Some, such as Charles Ives, blended familiar music in unusual ways.

In this excerpt from his String Quartet No. 2, Ives creates a musical “discussion” in which American folk tunes from North and South are quoted in opposition to each other.

Time: 4:31 – 5:08

Some, such as the Chinese-American composer Chen Yi, incorporate influences from non-western cultures.

This example from Yi’s Fiddle Suite uses the string quartet along with the Chinese erhu.

Others, such as Elliott Carter and Milton Babbitt, developed sophisticated, very carefully constructed compositional methods.

In this excerpt from Carter’s Variations for Orchestra (1955), sections within the orchestra are characterized uniquely—the woodwinds, for instance, are soft and slow-paced—and then the brass, percussion, and strings are layered on top of each other in a complex counterpoint.

Time: 0 – 0:55

Now, over a hundred years after the end of the “common practice” period, there is an enormous proliferation of musical styles. The dispersement of the musical community in favor of much more personal musical languages greatly heightened ambiguity.

Changing the Common Use of Musical Elements

Absence of Pulse

A steady pulse or “backbeat,” so crucial to pop music, jazz, and much world music, provides continuity and predictability: You tap your feet to the beat.

Duke Ellington: East St. Louis Toodle-Oo

A steady meter divides musical time into a fixed cycle of beats. Classical ballet and ballroom dancing depend on a steady meter.

Peter Tchaikovsky: “Waltz of the Flowers” from The Nutcracker ballet

Time: 0:55 – 1:57

Removing the steady pulse or meter disrupts the musical continuity and makes events much harder to predict.

There are two main ways to accomplish this: One is to make the pulse or meter erratic.

Igor Stravinsky: “Sacrificial Dance” from The Rite of Spring

Time: 0 – 0:24

The second is to remove the sense of pulse and meter altogether, creating what Pierre Boulez has termed “unstriated time.” In the following example from Boulez’s Eclat, the solitary, sporadic events seem to float freely, unanchored by meter or pulse.

Pierre Boulez: Eclat

Time: 1:30 – 2:04

Weakening the sense of pulse or meter heightens ambiguity by removing an important frame of reference to the listener.

Unpredictable Continuity

Musch music during the common practice era strove for maximum clarity. The listener has learned expectations of what will happen next in the composition. For instance, listen to the opening of J.S. Bach’s Prelude in E-flat from theWell-Tempered Clavier, Book I, which was published in 1722. As you listen, can you predict what happens next?

J. S. Bach: Prelude No. 7 / Well-Tempered Clavier, Book I

Time: 0 – 0:32

The first few exchanges between upper and lower registers created the expectation that the lower register will continue to imitate the upper. Sure enough, the lower register answers in fast motion, confirming our prediction.

A surprise occurs when one outcome is strongly anticipated but another one occurs. Ambiguity arises when multiple outcomes are all equally expected or no clear forecast can be made. Listen to the opening of the second movement of Igor Stravinsky’s Three Pieces for String Quartet, which was published in 1922. As you listen, can you predict what happens next in the music?

Igor Stravinsky: Three Pieces for String Quartet, II

Time: 1:17 – 2:00

This time, you were likely to have much less confidence in your prediction. In the Bach example, a pattern was established: the upper voice was repeatedly answered by the lower. Stravinsky does not establish a consistent pattern, making any predictions much more uncertain. When we cannot confidently forecast what will happen in the future, ambiguity is heightened.

Minimal Exposition

In music, expository statements (musical themes) establish the identity of a musical idea;

developmental passages put the idea into action. Most classical music operates like this: an idea is first introduced, then put into action.

J. S. Bach: “Contrapunctus IX” from The Art of the Fugue

When the exposition is abbreviated and development intensified, ambiguity is heightened.

Milton Babbit: Post-Partitions

In the most extreme cases, a modern work may consist exclusively of development. In such cases, the identity of the underlying material may be very difficult to perceive.

Lack of Resolution

In classical music, dissonance is a tendency tone that is considered unstable. A dissonance demands continuation: It must resolve to a stable tone, called a consonance.

Classical music makes an essential promise: All dissonances will resolve. Sometimes, resolutions are delayed; or new dissonances enter just as others are resolved. Eventually, however, the music will reach a state of repose and clarity.

Gustav Mahler: Symphony No. 1, IV

Time: 5:20 – 6:04

In progressive modern music, dissonance is frequently intensified and sustained way beyond classical expectations.

Henry Cowell: Tiger

Time: 0 – 0:45

In addition, there is a new paradigm: Dissonances no longer must resolve. Stability and clarification are no longer guaranteed.

Gyorgy Kurtág: Twelve Microludes, XI

The absence of resolution at a work’s close guarantees greater ambiguity. In the following example from Pierre Boulez’s Dérive (1984), a stable sound is sustained by the violin. The other instruments dart towards and away from this sound, never wholeheartedly coinciding with it.

Pierre Boulez: Dérive

Time: 5:20 – end

There is nothing that we can do to make Boulez’s ending sound secure. It is inherently more ambivalent.

Heightened Dissonance

In music theory, dissonance is a functional term. To listeners, though, “dissonant” is often a value judgment, typically meaning “harsh” and “unpleasant.” Those attributes, though, are subjective and carry strong negative connotations. Let us consider a different description. Acoustically, a stable sound is more “transparent:” It is easier to identify its inner constituents. A sound with a lot of dissonance is more “opaque:” The greater the amount of dissonance, the harder it is to analyze and interpret the sound.

Gyorgy Ligeti: “Kyrie” from Requiem

Time: 7:52 – 9:40

It is easy to understand, then, why modern composers might heighten dissonance: Not necessarily to make the music more strident but rather to increase the ambiguity by making the sounds harder to aurally decipher.

Harmonic Independence

The word harmony describes the notes that are sounding at the same time. In classical music, no matter how many instruments are playing, they will share the same harmony. As one harmony leads to another, the instruments will move together, partaking of the same notes. In addition to a steady pulse, harmonic coordination is the primary way that tonal music coheres. Harmony is the reason that the instruments “sound good together” even when they are playing independent lines.

Ludwig van Beethoven: Symphony No. 9, IV

Time: 18:50 – 20:10

The absence of harmonic coordination may create great ambiguity and complexity. Harmonic independence makes is much harder to get a “comprehensive” overview of how the instruments fit together.

The third movement of Luciano Berio’s Sinfonia (1968) dramatizes this effect. In this movement, the scherzo from Mahler’s Second Symphony is played continuously. On top of it, an elaborate collage of music and text is layered: graffiti from the walls of the Sorbonne, quotes from Samuel Beckett, and excerpts from classical and modern music. Strong clashes arise because the collage elements do not agree harmonically with the Mahler.

Gustav Mahler: Symphony No. 2, III Scherzo

Luciano Berio: Sinfonia

Time: 0 – 2:00

Harmonic independence does not mean that modern composers do not care how independent lines sound together. They do care, but they are trying to create ambiguity rather than clarity. Giving each instrument its own musical line which may complement others in intricate ways, leads to radically new resulting sounds.

Weak Structural Clarity

In classical music, united emphasis or “rhetorical reinforcement” is a primary means of creating structural clarity. In Beethoven’s Symphony No. 5, the third movement continues into the fourth without a break. The boundary between the movements is marked by strong rhetorical reinforcement: The dynamics, texture, meter, and speed all change at once to herald the opening of the fourth movement.

Ludwig van Beethoven, Symphony No. 5, III-IV

4:50 – 6:00

In progressive twentieth-century music, rhetorical reinforcement is often weak or absent. This makes the structural arrival points much more difficult to perceive. In Henri Dutilleux’s Ainsi la nuit…(1976), the individual movements are played without pause. However, the boundaries between movements are difficult to discern because there are conflicting aural cues.

Henri Dutilleux, Ainsi la nuit…(1976)

Time: 3:18 – 4:30

Perhaps you recognized that the second movement begins with the loud gesture played a little over a minute into the excerpt. However, this gesture does not have a greater perceptual priority than other potential markers, such as the long silences. As a result, you are likely to be far less certain about the formal boundary.

Silence

Many musical traditions treat silence as the “absence of music.” Silence is almost totally absent from pop music. In classical music, it is used sparingly: It may occur as a “breath” to short phrases or as a way to clearly separate one section of the form from another.

The opening of Mozart’s Symphony No. 40 (1788) consists of continuous sound until the arrival of the contrasting section, which is marked by silence:

Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart: Symphony No. 40, I

Time: 0 – 1:10

In some twentieth-century music, silence began to be treated as a musical material in its own right. Its musical information is limited: All we can analyze is how long it lasts. But, in seeking to heighten ambiguity, this limitation became a strength. We can read many possible meanings and inferences into silence: It is a hesitation, an interruption, a “trap door” into the unexpected.

Earl Kim: “Thither” from Then and Now

Time: 2:15 – 3:20

To John Cage, silence marked a musical event over which the composer had no control, which could function as a “window” into other sounds. His Imaginary Landscape No.4, is scored for twelve radios. The performers move the frequency and volume dials according to precisely timed instructions. Cage has no control over the resulting sound: It depends entirely on what is being broadcast that day. At one performance, none of the frequencies marked in the score coincided with stations in that location, resulting in a completely silent performance.

The greater the use of silence, the greater the ambiguity.

John Cage’s 4’33” explained: The music of silence

Noise

If silence is the “absence of sound,” then noise is “indiscriminate” or “indistinguishable” sound, in which it is impossible to tell the pitches or what instruments are playing. Classical music is generally purged of noise.

To progressive 20th-century composers, the inherent ambiguity of noise became very attractive.

Composers incorporated noise in their music in numerous ways. Some brought the outside world into the concert hall. For instance, to create his electronic composition Finnegan’s Wake, John Cage recorded sounds in the Dublin neighborhood where a scene from James Joyce’s novel on which the piece was based occurred; he then layered these in a complex collage.

John Cage: Roaratorio

Time: 0 – 1:10

Other composers asked for standard instruments to be played in non-traditional ways. In his string quartet Black Angels (1970), George Crumb has an amplified string quartet run their fingers rapidly up and down their fingerboards, creating a sound meant to evoke the frantic buzzing of insects.

George Crumb: Black Angels

Time: 0 – 1:10

As with silence, the more noise, the greater the ambiguity.

Ambiguous Notation

Classical music comes with detailed instructions. A classical score typically specifies the instrumentation, pitches, rhythms, speed, dynamics, and articulations. Not everything is marked with equal precision, i.e. tempo, leaving room for interpretation. However, the purpose of the score is to create a recognizable performance: Much more is shared between interpretations than differs. For instance, compare two performances of Beethoven’s Bagatelle, Opus 126, no.1 (1825).

Now compare the following two recordings of Earle Brown’s December 1952.

Earle Brown: December 1952 – performed by the Subtropics Festival Ensemble

Earle Brown: December 1952 – performed by David Tudor (piano)

Hard as it may be to believe, those are actually two performances of the same work. How can that possibly be? The instrumentation is different. The musical content—the pattern of sounds and silences–is totally different. Not a single detail is the same.

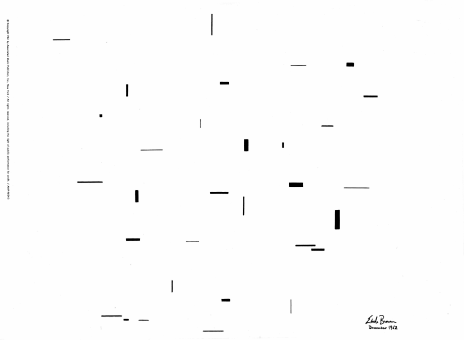

The sheet music score for Brown’s work is shown below:

The composer offers no suggestions as to how to interpret the image: All decisions are left up to the performer. Brown’s goal was to provide the impetus for a musical performance but not to impose an outcome. With such ambiguity in the notation, enormous variation in performance is possible.

Earle Brown writes:

”December 1952’ was written for one or more instruments and/or sound-producing media. The following note appears on a notebook page dated Oct. & Nov. ’52, but they are the basis of the composition ‘December 1952’ as well as being particularly relevant to ‘Four Systems’: “…to have elements exist in space…space as an infinitude of directions from an infinitude of points in space…to work (compositionally and in performance) to right, left, back, forward, up, down, and all points between…the score [being] a picture of this space at one instant, which must always be considered as unreal and/or transitory…a performer must set this all in motion (time), which is to say, realize that it is in motion and step into it…either sit and let it move or move through it at all speeds…[coefficient of] intensity and duration [is] space forward and back.”

Ambiguity in notation represents perhaps the greatest extreme reached in modern music. The more the musical text leaves open, the more it moves away from the constructive clarity of classical tonal music.

Listening with Intellect and an Open Mind

Listening to Ambiguity

In Samuel Beckett’s “Waiting for Godot,” two vagabonds—Vladimir and Estragon—await the arrival of a mysterious visitor, Godot. Godot’s arrival is anticipated, it is hoped for, it is repeatedly heralded–but it never happens. No matter how many times you see the play, Godot will never appear. Similarly, the ambiguities in a modern musical work are built in and can never be removed. Acknowledging this is the first step to a deeper understanding.

Listeners are so often frustrated because they expect the uncertainties eventually to be clarified—if only they knew more or could listen more attentively. Doing so does not remove the ambiguities, it only makes them more acute and palpable.

Thinking Clearly About Ambiguity

Once you learn to tolerate the ambiguity, you can begin to discover its source. Are pulse and meter absent or erratic? Is dissonance heightened? Is the structure unpredictable? Is there minimal exposition? Perpetual variation? Do noise and silence figure prominently? Any or all of these may contribute to the work’s open-endedness.

Considering the sources of the ambiguity will help you relate different pieces to each other and enable you to become more articulate about what you hear.

Be Prepared for More Personal Reactions

Modern works often do not strongly direct the listener’s attention: There may not be a clear hierarchy of theme and accompaniment; structural arrival points may be more subtle or evasive. Be prepared for your reaction to be more personal; and be prepared for your perspective to change with repeated hearings, as you focus on different aspects of the work. Do your best to not judge a work based on your first listening experience.

Celebrating Ambiguity

In the same way that a Jackson Pollock drip painting will never resolve itself into a clear image, the ambiguity in a progressive modern composition is irreversible. Whether it is now or in fifty or five hundred years, the only way to appreciate such music is to learn to sustain, tolerate, and celebrate the ambiguity. There’s nothing that we can do to make the ending of Boulez’s Dérive sound like the end of Beethoven’s 5th Symphony. We cannot remove the noise from Crumb’s Black Angels or make a single performance of Earle Brown’s December 1952 definitive. In an art form that is already abstract and non-verbal, heightening the ambiguity only increases feelings of isolation and uncertainty.

In addition, music is conventionally taught using concepts and terms specific to the common practice era. This training conditions listeners to certain expectations that modern music often fails to meet, leaving them baffled. To enjoy modern music, you must recognize the integrity of your own experience with the music—you must learn to trust your ears. You must also learn to abandon your preconceptions and listen in a style-independent way.

In life and in music, we often long for clarity. And yet, in so many ways, we are learning how deeply ambiguity is embedded in our experience and how acknowledging and tolerating it enlarges our spirit. Modern music offers one of the safest ways to experience ambiguity. If we can learn to listen to modern music with an open mind and careful attention, it may help us deal more patiently and constructively with a world filled with contradictions and paradoxes.

Licensing & Attributions

Adapted from “Making Music Modern” from Sound Reasoning

by Anthony Brandt

Edited by Francis Scully

Edited and additional content by Jennifer Bill