Chapter 5: Music of the Middle Ages

Introduction and Historical Context

Musical Timeline

Introduction to the Middle Ages and its Music

What do you think of when you hear the term the Middle Ages (450-1450)? For some, the semi-historical figures of Robin Hood and Maid Marian come to mind. Others recall Western Christianity’s Crusades to the Holy Land. Still, others may have read about the arrival in European lands of the bubonic plague or Black Death, as it was called. For most twenty-first-century individuals, the Middle Ages seem far removed. Although life and music were quite different back then, we hope that you will find that there are cultural threads that extend from that distant time to now.

We normally start studies of Western music with the Middle Ages, but of course, music existed long before then. The term Middle Ages or medieval period got its name to describe the time in between (or “in the middle of”) the ancient age of classical Greece and Rome and the Renaissance of Western Europe, which roughly began in the fifteenth century. Knowledge of music before the Middle Ages is limited but what what is known largely revolves around the Greek mathematician Pythagoras, who died around 500 B.C.E. (See his profile on a third-century ancient coin in figure 3.1.)

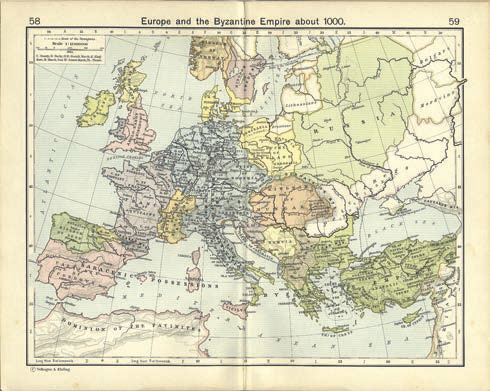

Pythagoras might be thought of as a father of the modern study of acoustics due to his experimentation with bars of iron and strings of different lengths. Images of people singing and playing instruments, such as those found on the Greek vases, provide evidence that music was used for ancient theater, dance, and worship. The Greek word musicka referred to not only music but also referred to poetry and the telling of history. Writings of Plato and Aristotle referred to music as a form of ethos (an appeal to ethics). As the Roman Empire expanded across Western Europe, so too did Christianity (see Figure 2.2, a map of Western Europe around 1000).

Considering that Biblical texts from ancient Hebrews to those of early Christians, provided numerous records of music used as a form of worship, the Empire used music to help unify its people: the theory was that if people worshipped together in a similar way, then they might also stick together during political struggles.

Later, starting around 800 CE, Western music is recorded in a notation that we can still decipher today. This brief overview of these five hundred years of the Roman Empire will help us better understand the music of the Middle Ages.

Historical Context for Music of the Middle Ages (800-1400)

During the Middle Ages, as during other periods of Western history, sacred and secular worlds were both separate and integrated. However, during this time, the Catholic Church was the most widespread and influential institution and leader in all things sacred. The Catholic Church’s head, the Pope, maintained political and spiritual power and influence among the noble classes and their geographic territories; the life of a high church official was not completely different from that of a noble counterpart, and many younger sons and daughters of the aristocracy found vocations in the church. Towns large and small had churches, spaces open to all: commoners, clergy, and nobles. The Catholic Church also developed a system of monasteries, where monks studied and prayed, often in solitude, even while making cultural and scientific discoveries that would eventually shape human life more broadly. In civic and secular life, kings, dukes, and lords wielded power over their lands and the commoners living therein. Kings and dukes had courts, gatherings of fellow nobles, where they forged political alliances, threw lavish parties, and celebrated both love and war in song and dance.

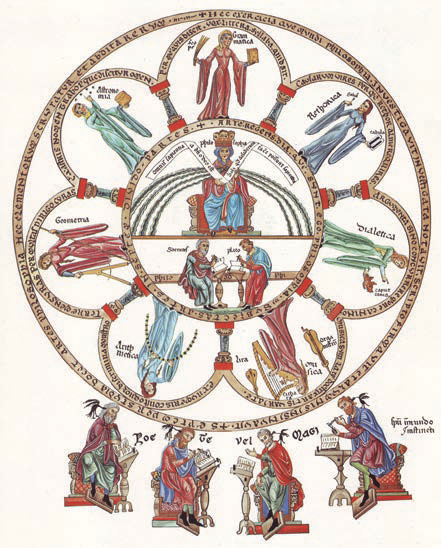

Many of the important historical developments of the Middle Ages arose from either the church or the court. One such important development stemming from the Catholic Church would be the developments of architecture. During this period, architects built increasingly tall and imposing cathedrals for worship through the technological innovations of pointed arches, flying buttresses, and large cut glass windows. This new architectural style was referred to as “gothic,” which vastly contrasts with the Romanesque style, with its rounded arches and smaller windows. Another important development stemming from the courts occurred in the arts. Poets and musicians, attached to the courts, wrote poetry, literature, and music, less and less in Latin—still the common language of the church—and increasingly in their own vernacular languages (the predecessors of today’s French, Italian, Spanish, German, and English). However, one major development of the Middle Ages spanned sacred and secular worlds: universities shot up in locales from Bologna, Italy, and Paris, France, to Oxford, England (the University of Bologna being the first). At university, a young man could pursue a degree in theology, law, or medicine. Music of a sort was studied as one of the seven liberal arts and sciences, specifically as the science of proportions. (Look for musical instruments [representing the delight of music] in this twelfth-century image of the seven liberal arts from the Hortus deliciarum (Garden of Delights) of the Herrad of Landsberg (Figure 3.5).

Music in the Middle Ages: An Overview

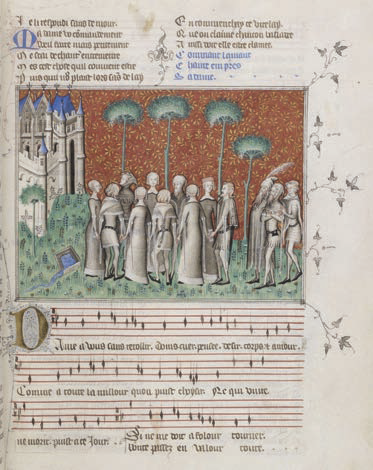

Not surprisingly, given their importance during the Middle Ages, both the Catholic Church and the network of aristocratic courts left a significant mark on music of the time. Much of the music from that era that was written down in notation and still exists comes from Christian worship or court entertainment. Churches and courts employed scribes and artists to write down their music in beautifully illuminated manuscripts such as this one that features Guillaume Machaut’s “Dame, a vous sans retollir,” discussed later. Churchmen such as the monk Guido of Arezzo devised musical systems such as “solfège” still used today.

As we study a few compositions from the Middle Ages, we will see the following musical developments at play:

- the development of musical texture from monophony to polyphony, and

- the shift from music whose rhythm is hinted at by its words, to music that has what we refer to today as meter.

Music for Medieval Christian Worship

The earliest music of Catholic Christianity was chant, that is, monophonic a cappella music, most often sung in worship. As you learned in the first chapter of this book, monophony refers to music with one melodic line that may be performed by one or many individuals at the same time. Largely due to the belief of some Catholics that instruments were too closely associated with secular music, instruments were rarely used in medieval worship; therefore, most chant was sung a cappella, or without instruments. As musical notation for rhythm had not yet developed, the exact development of rhythm in chant is uncertain. However, based on church tradition (some of which still exists), it is believed that the rhythms of medieval chants were guided by the natural rhythms provided by the words.

Medieval Catholic worship included services throughout the day. The most important of these services was the Mass, at which the Eucharist, (also known as communion), was celebrated (this celebration includes the consumption of bread and wine representing the flesh and blood of Jesus Christ). The five chants of the mass (the Kyrie, Gloria, Credo, Sanctus, and Agnus Dei) were typically included in every Mass, no matter what date in the church calendar. Catholics, as well as some Protestants, still use this liturgy in worship today.

In the evening, one might attend a Vespers service, at which chants called hymns were sung. Hymns, like most of the rest of the Catholic liturgy, were sung in Latin. Hymns most often featured four-line strophes in which the lines were generally the same length and often rhymed. Each strophe of a given hymn was sung to the same music, and for that reason, we say that hymns are in strophic form. Hymns, like most chants, generally had a range of about an octave, which made them easy to sing.

Throughout the Middle Ages, Mary, the mother of Jesus, referred to as the Virgin Mary, was a central figure in Catholic devotion and worship. Under Catholic belief, she is upheld as the perfect woman, having been chosen by God to miraculously give birth to the Christ while still a virgin. She was given the role of intercessor, a mediator for the Christian believer with a petition for God, and as such appeared in many medieval chants.

Focus On Composition

Ave Generosa by Hildegard of Bingen (Twelfth Century)

Many composers of the Middle Ages will forever remain anonymous. Hildegard of Bingen (1098-1179) from the German Rhineland is a notable exception. At the age of fourteen, Hildegard’s family gave her to the Catholic Church where she studied Latin and theology at the local monastery. Known for her religious visions, Hildegard eventually became an influential religious leader, artist, poet, scientist, and musician. She would go on to found three convents and become an abbess, the chief administrator of an abbey.

Writing poetry and music for her fellow nuns to use in worship was one of many of Hildegard’s activities, and the hymn “Ave Generosa” is just one of her many compositions. This hymn has multiple strophes in Latin that praise Mary and her role as the bearer of the Son of God. The manuscript contains one melodic line that is sung for each of the strophes, making it a strophic monophonic chant. Although some leaps occur, the melody is conjunct. The range of the melody line, although still approachable for the amateur singer, is a bit larger than other church chants of the Middle Ages. The melody also contains melismas at several places. A melisma is the singing of multiple pitches on one syllable of text. Overall, the rhythm of the chant is syllabic, meaning it follows the rhythm of the syllables of the text.

Chant is by definition monophonic, but scholars suspect that medieval performers sometimes added musical lines to the texture, probably starting with drones (a pitch or group of pitches that were sustained while most of the ensemble sang together the melodic line). Performances of chant music today often add embellishments such as occasionally having a fiddle or small organ play the drone instead of being vocally incorporated. Performers of the Middle Ages possibly did likewise, even if prevailing practices called for entirely a cappella worship.

Listening Guide: Ave Generosa

- Composer: Hildegard of Bingen

- Artist: UCLA Early Music Ensemble;

- Soloist Arreanna Rostosky;

- Audio & video by Umberto Belfiore;

Listen through 3:17 for the first four strophes.

Other things to listen for:

- Its melodic line is mostly conjunct.

- Its melody contains many melismas.

- It has a Latin text sung in a strophic form.

|

Timing |

Performing Forces, Meldoy and Texture |

Text and From |

|

0:00 |

Solo vocalist enters with first line using a monophonic texture. The melody opens with an upward leap and then moves mostly by step: conjunct |

Strophe 1: Ave, generosa, “Hail generous one” |

|

0:10 |

Group joins with line two, some singing a drone pitch. The melody continues mostly conjunctly, with melismas added. Since the drone is improvised, this is still monophony. |

Strophe 1 continues: Glorio- sa et intacta puella… “Noble, glorious, and whole woman…” |

|

0:49 |

Repetition of the melody to new words sung by all with monophonic texture (the drone continues) |

Strophe 2: Nam hec superna infusio in te fuit… “The essences of heaven flooded into you…” |

|

1:37 |

Repetition of the melody to new words sung by all with monophonic texture (the drone continues) |

Strophe 3: O pulsherrima et dulcissima… “O lovely and tender one…” |

|

2:34 |

Repetition of the melody to new words sung by all with monophonic texture (the drone continues) |

Strophe 4: Venter enim tuus gaudium havuit… “Your womb held joy…” |

The Emergence of Polyphonic Music for the Medieval Church

Initial embellishments such as the addition of a musical drone to a monophonic chant were probably improvised during the Middle Ages. With the advent of musical notation that could indicate polyphony, composers began writing polyphonic compositions for worship, initially intended for select parts of the Liturgy to be sung by the most trained and accomplished of the priests or monks leading the mass. Originally, these polyphonic compositions featured two musical lines at the same time; eventually, third and fourth lines were added. Polyphonic liturgical music, originally called organum, emerged in Paris around the late twelfth and thirteenth centuries. In this case, growing musical complexity seems to parallel growing architectural complexity.

Composers wrote polyphony so that the cadences, or ends of musical phrases and sections, resolved to simultaneously sounding perfect intervals. Perfect intervals are the intervals of fourths, fifths, and octaves. Such intervals are called perfect because they are the first intervals derived from the overtone series (see chapter one). As hollow and even disturbing as perfect intervals can sound to our modern ears, the Middle Ages used them in church partly because they believed that what was perfect was more appropriate for the worship of God than the imperfect.

In Paris, composers also developed an early type of rhythmic notation, which was important considering that individual singers would now be singing different musical lines that needed to stay in sync. By the end of the fourteenth century, this rhythmic notation began looking a little bit like the rhythmic notation recognizable today. Beginning a music composition, a symbol was written indicating something like our modern meter symbols (see chapter two). This symbol told the performer whether the composition was in two or in three and laid out the note value that provided the basic beat. Initially almost all metered church music used triple time, because the number three was associated with perfection and theological concepts such as the trinity.

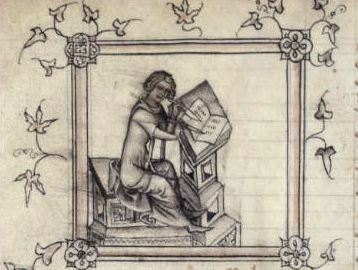

Elsewhere in what is now France, Guillaume de Machaut (c. 1300-13) emerged as the most important poet and composer of his century. He is the first composer about which we have much biographical information, due in part to the fact that Machaut himself, near the end of his life, collected his poetry into volumes of manuscripts, which include a miniature image of the composer (see Figure 3.9 of Machaut at work from a fourteenth century manuscript). We know that he traveled widely as a cleric and secretary for John, the King of Bohemia. Around 1340, he moved to Reims (now in France), where he served as a church official at the cathedral. There he had more time to write poetry and music, which he seems to have continued doing for some time.

Focus Composition

Agnus Dei from the Nostre Dame Mass (c. 1364 Ce) by Guillaume de Machaut

It is believed that Machaut wrote his Mass of Nostre Dame around 1364. This composition is famous because it was one of the first compositions to set all five movements of the mass ordinary as a complete composition. These movements are the pieces of the Catholic liturgy comprising every Mass, no matter what time of the year. A movement in music refers to a musical section that sounds complete but that is part of a larger musical composition. Musical connections between each movement of this Mass cycle—the Kyrie, Gloria, Credo, Sanctus, and Agnus Dei—suggest that Machaut intended them to be performed together. The Agnus Dei was composed after the death of Machaut’s brother in 1372. This Mass was likely performed every week in a side chapel of the Reims Cathedral. Medieval Catholics commonly paid for Masses to be performed in honor of their deceased loved ones.

As you listen to the Agnus Dei movement from the Nostre Dame Mass, try imagining that you are sitting in that side chapel of the cathedral at Reims, a cathedral that looks not unlike the Cathedral of Notre Dame in Paris. Its slow tempo might remind us that this was music that memorialized Machaut’s dead brother, and its triple meter allegorized perfection. Remember that although its perfect intervals may sound disturbing to our ears, for those in the Middle Ages they symbolized that which was most appropriate and musically innovative.

Listening Guide: La Messe de Nostre Dame

- Composer: Guillaume de Marchaut

- Composition: Agnus Dei from the Nostre Dame Mass

- Date: c. 1364 CE

- Genre: Movement from the Ordinary of the Mass

- Form: A – B – A

Nature of Text: Latin words from the Mass Ordinary: Agnus Dei, qui tollis peccata mundi, Miserere nobis” (Lamb of God, who takes away the sin, have mercy on us)

Performing Forces: small ensemble of vocalists

What we want you to remember about this composition:

- It is part of the Latin mass.

- It uses four-part polyphony.

- It has a slow tempo.

Other things to listen for:

- Its melodies lines have a lot of melismas

- It is in triple meter, symbolizing perfection

- It uses simultaneous intervals of fourths, fifths, and octaves, also symbolizing perfection.

- Its overall form is A-B-A.

Oxford Camerata directed by Jeremy Summerly

| Timing | Performing Forces, Melody, and Texture | Text & Form |

| 0:00 | Small ensemble of men singing in four-part polyphony; a mostly conjunct melody with a lot of melismas in triple meter at a slow tempo. The section ends with a cadence on open, hollow-sounding harmonies such as octaves and fifths. | A: Agnus Dei, qui tollis peccata mundi, Miserere nobis |

| 1:11 | This section begins with faster notes sung by the alto voice. Note that it ends with a cadence to hollowing- sounding intervals of the fifth and octave, just like the first section had. | B: Agnus Dei, qui tollis peccata mundi, Miserere nobis |

| 2:27 | Same music as at the beginning. | A: Agnus Dei, qui tollis peccata mundi, Miserere nobis |

Music in Medieval Courts

Like the Catholic Church, medieval kings, dukes, lords and other members of the nobility had resources to sponsor musicians to provide them with music for worship and entertainment. Individuals roughly comparable to today’s singer-songwriters served courts throughout Europe. Like most singer-songwriters, love was a favored topic. These poet-composers also sang of devotion to the Virgin Mary and of the current events of the day.

Many songs that merge these two focus points appear in a late thirteenth-century manuscript called the Cantigas de Santa Maria (Songs for the Virgin Mary), a collection sponsored by King Alfonso the Wise who ruled the northwestern corner of the Iberian peninsula. Cantigas de Santa Maria also includes many illustrations of individuals playing instruments. The musician in Figure 3.10 is playing a rebec and the one to the right a lute. Elsewhere in the manuscript these drummers and fifers appear (see Figure 3.11). These depictions suggest to us that, outside of worship services, much vocal music was accompanied by instruments. It is believed that such songs as these were also sung by groups and used as dance music, especially as early forms of rhythmic notation indicate simple and catchy patterns that were danceable. Other manuscripts also show individuals dancing to the songs of composers such as Machaut.

Video – Description and demonstration of crumhorns. Andrew Broadwater and Jacob Lodico, crumhorns; Kevin Shannon, baroque guitar; Mark Cudek, long drum

Focus Composition

Song of Mary, No. 181: “The virgin will aid those who most love her”

“The Virgin will aid those who most love her,” is one of over four hundred songs praising the Virgin Mary in the Cantigas de Santa Maria described above. “The Virgin will aid those who most love her” praises Mary for her help during the crusades in defeating a Moroccan king in the city of Marrakesh. It uses a verse and refrain structure similar to those discussed in chapter one. Its two-lined chorus (here called a refrain) is sung at the beginning of each of the eight four-lined strophes that serve as verses. The two-line melody for the refrain is repeated for the first two lines of the verse; a new melody then is used for the last two lines of the verse. In the recent recording done by Jordi Savall and his ensemble, a relatively large group of men and women sing the refrains, and soloists and smaller groups of singers perform the verses. The ensemble also includes a hand drum that ar- ticulates the repeating rhythmic motives, a medieval fiddle, and a lute, as well as medieval flutes and shawms, near the end of the excerpt below. These parts are not notated in the manuscript, but it is likely that similar instruments would have been used to accompany this monophonic song in the middle ages.

Listening Guide: Song of Mary, No. 181

- Composer: Anonymous

- Composition: Song of Mary, No. 181: “The Virgin will aid those who most love her” (Pero que seja a gente d’outra lei [e]descreuda)

- Date: c. 1275

- Genre: Song

- Form: Refrain [A] & verses [ab] = A-ab

Nature of Text: Refrain and strophes in an earlier form of Portuguese, praising the Virgin Mary

Performing Forces: small ensemble of vocalists, men and women singing together and separately

What we want you to remember about this composition:

- It is music for entertainment, even though it has a sacred subject.

- It is monophonic.

- Its narrow-ranged melody and repetitive rhythms make it easy for non-professionals to sing.

Other Things To Listen For:

- In this recording, the monophonic melody is sung by men and women and is played by a medieval fiddle and lute; a drum plays the beat; near the end of the excerpt, you can also hear flutes and shawms.

- Its musical form is A-ab; meaning that the refrain is always sung to the same music.

Medieval poet composers also wrote a lot of music about more secular love, a topic that continues to be popular for songs to the present day. Medieval musicians and composers, as well as much of European nobility in the Middle Ages, were particularly invested in what we call courtly love. Courtly love is love for a person, without any concern for whether or not the love will be returned. The speakers within these poems recounted the virtues of their beloved, acknowledging the impossibility of ever consummating their love and pledging to continue loving their beloved to the end of their days.

Guillaume de Machaut, who wrote the famous Mass of Nostre Dame discussed above, also wrote many love songs, some polyphonic and others monophonic. In his “Lady, to you without reserve I give my heart, thought and desire,” a lover admires his virtuous beloved and pledges undying love, even while suspecting that they will remain ever apart. Like “The Virgin will aid,” its words are in the original French. Also like “The Virgin will aid,” it consists of a refrain that alternates with verses. Here the refrain and three verses are in a fixed medieval poetic and musical form that can be notated as Abba-Abba-Abba-Abba. Machaut’s song, written over fifty years after “The Virgin will aid,” shows medieval rhythms becoming more complex. The notes are in groups of three, but the accentuation patterns often change. It is suspected that this song was also used as dance music, given the illustration of a group dancing in a circle appearing above its musical notation in Machaut’s manuscript. Songs like this were most likely sung with accompaniment, even though this accompaniment wasn’t notated; the recording excerpt in the link below uses tambourine to keep the beat.

Listening Guide: Dame, à vous sans retollir

Performed by Studio der Frühen Musik

- Composer: Guillaume de Machaut

- Composition: “Lady, to you without reserve I give my heart, thought and desire” (Dame, à vous sans retollir)

- Date: Fourteenth century

- Genre: song

- Form: Refrain [A] & Verses [bba]

Nature of Text: French poem about courtly love with a refrain alternating with three verses.

Performing Forces: soloist alternating with small ensemble of vocalists

What we really want you to remember about this composition:

- It is a French song about courtly love.

- It is monophonic, here with tambourine articulating the beats

- Its form consists of an alternation of a refrain and verses

Other things to listen for:

- Its melodic line is mostly conjunct, the range is a little over an octave, and it contains several short melismas.

- Its specific form is Abba, which repeats three times

|

Timing |

Performing Forces, Melody and Texture |

Text and Form |

|

0:00 |

Small group of women singing in monophonic text with tambourine; Mostly conjunct melody with a narrow range; Notes fall in rhythmic groups of three, but the accent patterns change often |

A: Refrain |

|

0:14 |

Female soloist still in monophonic texture without tambourine; the b phrase is mostly conjunct, starts high and descends, repeats, then returns to the a phrase as heard in the refrain |

bba: Verse |

|

0:40 |

Same music as in the A phrase above with the words of the refrain |

A: Refrain |

|

0:53 |

Female soloist as heard above to new words |

bba: Verse |

|

1:18 |

As heard in the Refrain above, words and music |

A: Refrain |

|

1:31 |

As heard above verses, with new words |

bba: Verse |

|

1:37 |

As heard in the Refrain above, words and music |

A: Refrain |

Figure 3.12 Beatriz de Dia Author: Bibliothèque Nationale, MS cod. fr. 12473 Source: Wikimedia Commons License: Public Domain

Focus on Women in Music

Beatriz, Countess of Dia – Men wrote and composed most of the poetry and music, but among the troubadours were a few women, who sang of courtly love from a feminine perspective. One of the most celebrated was the Countess of Dia, sometimes identified as Beatriz. She was active in Provence probably around 1175. She was married to a count, William of Poitiers, though her music often refers to her lover, the troubadour Raimbaut d’Orange. Her love song A chantar m’er is the only poem by a trobairitz (female troubadour) to survive with music. It reverses the usual gender roles found in medieval love songs. Instead of the male pining for an unreachable (and unheard) woman, here the woman is given a voice. She laments the dismissive treatment she receives from her knight.

Listening Map

- Title: A chantar m’er (I Must Sing), ca. 1175 by Beatriz, Countess of Dia

- Artist: Iordi Savall

- Genre: Troubadour song

- Texture: Monophonic melody

- Form: ABABCDB

Chapter Summary

In this chapter, we have studied music that dates back almost 1500 years from today. In some ways, it differs greatly from our music today, but some continuous threads exist. Individuals in the Middle Ages used music for worship and entertainment, just as occurs today. They wrote sacred music for worship and also used sacred ideas in entertainment music. Music for entertainment included songs about love, religion, and current events as well as music that might be danced to. Though the style and form of their music is quite different from ours in many ways, some aspects of musical style have not changed. Conjunct music with a relatively narrow range is still a typical choice in folk and pop music, owing to the fact that it is easy for even the amateur to sing. Songs in strophic form and songs with a refrain and contrasting verses also still appear in today’s pop music. As we continue on to study music of the Renaissance, keep in mind these categories of music that remain to the present day.

Glossary

- A cappella – vocal music without instrumental accompaniment

- Cadence – the ending of a musical phrase providing a sense of closure, often through the use of one chord that resolves to another

- Chant – text set to a melody written in monophonic texture with un-notated rhythms typically used in religious worship

- Courtly Love – love for a beloved, without any concern for whether or not the love will be returned, called “courtly” because it was praised by those participating in medieval courts

- Drone – a sustained pitch or pitches often found in music of the middle ages or earlier and in folk music

- Hymn – religious song most generally having multiple strophes of the same number and length of lines and using strophic form

- Mass – Catholic celebration of the Eucharist consisting of liturgical texts set to music by composers starting in the middle ages

- Melisma – multiple pitches sung to one syllable of text

- Polyphony – musical texture that simultaneously features two or more relatively independent and important melodic lines

- Refrain – a repeating musical section, generally also with repeated text; sometimes called a “chorus”

- Rhythm According to the Text – rhythm that follows the rhythm of the text and is not notated

- Solfège– A method of sight singing that uses the syllables do (originally ut), re, mi, fa, sol (so), la, and si (ti) to represent the seven principal pitches of the scale, most commonly the major scale. The fixed-do system uses do for C, and the moveable-do system uses do for whatever key the melody uses (thus B is do if the piece is in the key of B). The relative natural minor of a scale may be represented by beginning at la. https://www.yourdictionary.com/solfege

- Song – a composition sung by voice(s)

- Strophe – section of a poem or lyric text generally of a set number of lines and line length; a text may have multiple strophes

- Strophic – musical form in which all verses or strophes of a song are sung to the same music

- Syllabic – music in which each syllable of a text is set to one musical note

- Verse and Refrain Form – a musical form (sometimes referred to as verse and chorus) in which one section of music is sung to all the verses and a different section of music is sung to the repeating refrain or chorus

Media Attributions

- Pythagoras coin © Wikipedia is licensed under a Public Domain license

- Map of Europe 1000 AD © Wikipedia is licensed under a Public Domain license

- Notre Dame © Wikipedia is licensed under a CC0 (Creative Commons Zero) license

- A Map of Europe and the Byzantine Empire about 1000AD © Wikipedia is licensed under a Public Domain license

- Hortus Deliciarum © Wikipedia is licensed under a Public Domain license

- Guillaume de Machaut © Wikipedia is licensed under a Public Domain license

- The Virgin Mary © Wikipedia is licensed under a Public Domain license

- Depiction of Hildegard of Bingen © Wikipedia is licensed under a Public Domain license

- Depiction of Guillaume de Machaut © Wikipedia is licensed under a Public Domain license

- Rebec and Lute Players © Wikipedia is licensed under a Public Domain license

- Drummers and fifers © Wikipedia is licensed under a Public Domain license

- Beatriz de Dia © Wikipedia is licensed under a Public Domain license