Chapter 6: Music of the Renaissance

Objectives

- Demonstrate knowledge of historical and cultural contexts of the Renaissance

- Recognize musical styles of the Renaissance

- Identify important genres and uses of music of the Renaissance

- Identify selected music of the Renaissance aurally and critically evaluate its style and uses

- Compare and contrast music of the Renaissance with their own contemporary music

Key Terms and individuals

- Anthem

- Chanson

- Chapel Master

- Consort

- Counter-Reformation

- Galliard

- Giovanni Pierluigi da Palestrina

- Jig

- Josquin des Prez

- Madrigal

- Martin Luther

- Motet

- Pavanne

- Reformation

- Renaissance

- Thomas Weelkes

- William Byrd

- William Kemp

- Word painting

Introduction and Historical Context

What is the Renaissance?

The term Renaissance literally means “rebirth.” As a historical and artistic era in Western Europe, the Renaissance spanned from the late 1400s to the early 1600s. The Renaissance was a time of waning political power in the church, somewhat as a result of the Protestant Reformation. Also during this period, the feudal system slowly gave way to developing nation-states with centralized power in the courts. This period was one of intense creativity and exploration. It included such luminaries as Leonardo da Vinci, Christopher Columbus, Ferdinand Magellan, Nicolaus Copernicus, and William Shakespeare. The previous medieval period was suppressive, firmly established, and pious. The Renaissance, however, provided the thinkers and scholars of the day with a revival of Classical (Greek and Roman) wisdom and learning after a time of papal restraint. This “rebirth” laid the foundation for much of today’s modern society, where humans and nature rather than religion become the standard for art, science, and philosophy.

![The fresco depicts a congregation of ancient philosophers, mathematicians, and scientists, with Plato and Aristotle featured in the center. The identities of most figures are ambiguous or discernable only through subtle details or allusions;[1] among those commonly identified are Socrates, Pythagoras, Archimedes, Heraclitus, Averroes, and Zarathustra. Additionally, Italian artists Leonardo da Vinci and Michelangelo are believed to be portrayed through Plato and Heraclitus, respectively.[2][3] Raphael included a self-portrait beside Ptolemy.](https://rotel.pressbooks.pub/app/uploads/sites/27/2024/03/image5-2.png)

The School of Athens (1505), Figure 3.1, by Raphael, demonstrates the strong admiration, influence, and interest in previous Greek and Roman culture. The painting depicts the Greek philosophers Aristotle and Plato (center), with Plato depicted in the likeness of Leonardo da Vinci.

Renaissance Timeline

Occurrences at the end of the Middle Ages accelerated a series of intellectual, social, artistic, and political changes and transformations that resulted in the Renaissance. By the 1500s, Catholic liturgical music had become extremely complex and ornate. Composers such as Josquin des Prez and Palestrina were composing layered Masses that utilized musical textures such as polyphony and imitative counterpoint (more on these techniques later). The mass is a sacred choral composition historically composed as worship liturgy.

The complexity of the music in the Catholic Mass garnered criticism from Martin Luther, a Roman Catholic priest and the eventual father of the Protestant Reformation, who complained that the meaning of the words of the mass formal worship and liturgy were lost in the beautiful polyphony of the music. Also, Catholic Masses were always performed in Latin, a language seldom used outside the church. Early Protestant hymns stripped away contrapuntal textures, utilized regular beat patterns, and set biblical texts in German. Martin Luther himself penned a few hymns, many of which the great classic composer Johann Sebastian Bach would revisit about 125 years later.

Renaissance Humanism

The Humanism movement was one which expressed the spirit of the Renaissance era that took root in Italy after Eastern European scholars fled from Constantinople to the region bringing with them books, manuscripts, and the traditions of Greek scholarship. Humanism is a major paradigm shift from the ways of thought during the medieval era where a life of penance in a feudal system was considered the accepted standard of life.

As a part of this ideological change, there was a major intellectual shift from the dominance of scholars/clerics of the medieval period (who developed and controlled the scholastic institutions) to the secular men of letters. Men of letters were scholars of the liberal arts who turned to the classics and philosophy to understand the meaning of life.Humanism has several distinct attributes as it focuses on human nature, its diverse spectrum, and all its accomplishments. Humanism combines all the truths found in different philosophical and theological schools. It emphasizes and focuses on the dignity of man, and studies mankind’s struggles over nature.

Medieval vs. Renaissance

Rebirth of Ancient Civilizations

Predecessors to the Renaissance and the Humanist movement include Dante and Petrarch. In 1452, after the fall of Constantinople, there was a considerable boost in the Humanist movement. Humanism was accelerated by the invention of the printing press, which permitted mass reproduction of the classical text—once only found in hand-written manuscripts—and the availability of literature improved immensely. Thus, literacy among the common people increased dramatically. The scholastic and intellectual stimulation of the general public facilitated by Humanism initiated a power and knowledge shift from the land-owning upper class and the church to the individual. This shift facilitated and contributed to the beginning of the Reformation. As mentioned above, Martin Luther was a leading religious reformer who challenged the authority of the central Catholic Church and its role in governance, education, and religious practices. Like most other European groups of the era, the Humanists at the time were divided in their support of the reformation and counter-reformation movements.

Symmetry and Perspective in Art

The shift away from the power and authority of the church between the Medieval period and the Renaissance period is not only evident in music but is also found in the visual arts. Artists and authors of the Renaissance became interested in classical mythology and literature. Artists created sculptures of the entire human body, demonstrating a direct lineage from ancient Greek culture to the Renaissance. In the Middle Ages, such depictions of the nude body were thought to be objects of shame or in need of cover. Artists of the Middle Ages were more focused on religious symbolism than the lifelike representation created in the Renaissance era. Medieval artists perceived the canvas as a flat medium/surface on which subjects are shown very two-dimensionally. Painters of the Renaissance were more interested in portraying real-life imagery in three dimensions on their canvas. See the evolution of the Virgin Mary from the Medieval period to the Renaissance period in Figures 3.4, 3.5, and 3.6 above. You can see the shift from the religious symbolism to the realistic depiction of the features of the human bodies.

Raphael and Leonardo da Vinci focused on portraying realism, utilizing linear perspective and creating illusions of space in their works. A geometric system was effectively used to create space and the illusion of depth. This shift from religious symbolism to the real portrayal of the human is representative of the decline of the church in the arts as well as music. Music outside of the church, secular music, increased in importance.

The Protestant Reformation

In the Middle Ages, people were thought to be parts of a greater whole: members of a family, trade guild, nation, and church. At the beginning of the Renaissance, a shift in thought led people to think of themselves as individuals, sparked by Martin Luther’s dissent against several areas and practices within the Catholic Church. On October 31, 1517, Luther challenged the Catholic Church by posting The Ninety-Five Theses on the doors of the Castle Church in Wittenberg, Germany. The post stated Luther’s various beliefs and interpretations of Biblical doctrine, which challenged the many practices of the Catholic Church in the early 1500s. Luther felt that educated/literate believers should be able to read the scriptures and become individual church entities themselves. With the invention of the Gutenberg Press, copies of the scriptures and hymns became available to the masses, which helped spread the Reformation. The empowerment of the common worshiper or middle class continued to fuel the loss of authority of the church and upper class.

Gutenberg Press

Few inventions have had the significance of modernization as the Gutenberg Press. Up until the invention of the press, the earliest forms of books with edge binding, similar to the type we have today, called codex books, were hand-produced by monks. This process was quite slow, costly, and laborious, often taking months to produce smaller volumes and years to produce a copy of the Bible and hymn books of worship.

Gutenberg’s invention of a much more efficient printing method made it possible to distribute a large amount of printed information at a much accelerated and labor-efficient pace. The printing press enabled the printing of hymn books for the middle class and further expanded the involvement of the middle class in their worship service, a key component in the Reformation. Gutenberg’s press served as a major engine for the distribution of knowledge and contributed to the Renaissance, Scientific Revolution, and Protestant Reformation.

Columbus’s Voyage

Columbus’s discovery of the New World in 1492 also contributed to the spirit and spread of the Humanist movement. The discovery of new land and the potential for colonization of new territory added to the sense of infallibility and ego of the Europeans. The human spirit of all social classes was invigorated. The invigoration of the middle class influenced the arts and the public’s hunger for art and music for the vast middle-class population.

Music of The Renaissance

Characteristics of Renaissance Music include steady beat, balanced phrases (the same length), polyphony (often imitative), increasing interest in text-music relationships, the printing of music using movable type by Ottaviano Petrucci, and a growing merchant class singing/playing music at home. Word painting was utilized by Renaissance composers to represent poetic images musically. For example, an ascending melodic line would portray the text “ascension to heaven.” Or a series of rapid notes would represent running.

Art music in the Renaissance served three basic purposes:

- Worship in both the Catholic and burgeoning Protestant Churches.

- Music for the entertainment and edification of the courts and courtly life.

- Music for dance.

Playing musical instruments became a form of leisure and a significant, valued pastime for every educated person. Guests at social functions were expected to contribute to the evening’s festivities through instrumental performances.

Much of the secular music in the Renaissance was centered on courtly life. Vocal music ranged from chansons (or songs) about love and courtly intrigue to madrigals about nymphs, fairies, and, well, you name it. Both chansons and madrigals were often set for one or more voices with plucked-string accompaniment, such as by the lute, a gourd-shaped instrument with frets and a raised strip on the fingerboard, somewhat similar to the modern guitar.

Madrigals, musical pieces for several solo voices set to a short poem, originated in Italy around 1520. Most madrigals were about love and were published by the thousands and learned and performed by cultured aristocrats. Similar to the motet, a madrigal combines both homophonic and polyphonic textures. Unlike the motet, the madrigal is secular and utilizes unusual harmonies and word painting more often. Many of the refrains of these madrigals utilized the text “Fa La” to fill the gaps in the melody or to possibly cover risqué or illicit connotations. Sometimes madrigals are referred to as Renaissance Fa La songs.

A volume of translated Italian madrigals was published in London during the year 1588, the year of the defeat of the Spanish Armada. This sudden public interest facilitated a surge of English madrigal writing as well as a spurt of other secular music writing and publication. This music boom lasted for thirty years and was as much a golden age of music as British literature was with Shakespeare and Queen Elizabeth I. The rebirth in both literature and music originated in Italy and migrated to England; the English madrigal became more humorous and lighter in England as compared to that of Italy.

Renaissance music was mostly polyphonic in texture. Comprehending a wide range of emotions, Renaissance music nevertheless portrayed all emotions in a balanced and moderate fashion. Extreme use of contrasts in dynamics, rhythm, and tone color does not occur. The rhythms in Renaissance music tend to have a smooth, soft flow instead of a sharp, well-defined pulse of accents.

Composers enjoyed imitating sounds of nature and sound effects in their compositions. The Renaissance period became known as the golden age of a cappella choral music because choral music did not require an instrumental accompaniment. Instrumental music in the Renaissance remained largely relegated to social purposes such as dancing, but a few notable virtuosos of the time, including the English lutenist and singer John Dowland, composed and performed music for Queen Elizabeth I, among others.

John Dowland was a lutenist in 1598 in the court of Christian IV and later in 1612 in the court of King James I. He is known for composing one of the best songs of the Renaissance period, Flow, my Teares. This imitative piece demonstrates the melancholy humor of the time period.

For more information on Dowland, and the lyrics to Flow My Tears.

The instruments utilized during the Renaissance era were quite diverse. Local availability of raw materials for the manufacture of the instrument often determined its assembly and accessibility to the public. A Renaissance consort is a group of Renaissance instrumentalists playing together. A whole consort is an ensemble performing with instruments from the same family. A broken consort is an ensemble composed of instruments from more than one family.

Instruments from the Medieval and Renaissance

Style Overview

Medieval Music

- Mainly monophony

- Majority of the music’s rhythm comes from the text

- Use of perfect intervals such as fourths, fifths, and octaves for cadences

- Most music comes from the courts or church

- Music instruction predominantly restricted to the church and patron’s courts

Renaissance Music

- Mainly polyphony (much is imitative polyphony/overlapped repetition—please see music score below)

- Majority of the music’s rhythms is indicated by musical notation

- Growing use of thirds and triads

- Music – text relationships increasingly important with the use of word painting

- Invention of music publishing

- Growing merchant class increasingly acquires musical skills

Worship Music

During the Renaissance from 1442 to 1483, church choir membership increased dramatically in size. The incorporation of entire male ensembles and choirs singing in parts during the Renaissance is one major difference from the Middle Ages’ polyphonic church music, which was usually sung by soloists. As the Renaissance progressed, the church remained an important supporter of music, and musical activity gradually shifted to secular support. Royalty and the wealthy of the courts seeking after and competing for the finest composers replaced what was originally church supported. The motet and the mass are the two main forms of sacred choral music of the Renaissance.

Motet

The motet, a sacred Latin text polyphonic choral work, is not taken from the ordinary of the mass. A contemporary of Leonardo da Vinci and Christopher Columbus, Josquin des Prez was a master of Renaissance choral music. Originally from the region that is today’s Belgium, Josquin spent much of his time serving in chapels throughout Italy and partly in Rome for the papal choir. Later, he worked for Louis XII of France and held several church music directorships in his native land. During his career, he published masses, motets, and secular vocal pieces, and was highly respected by his contemporaries.

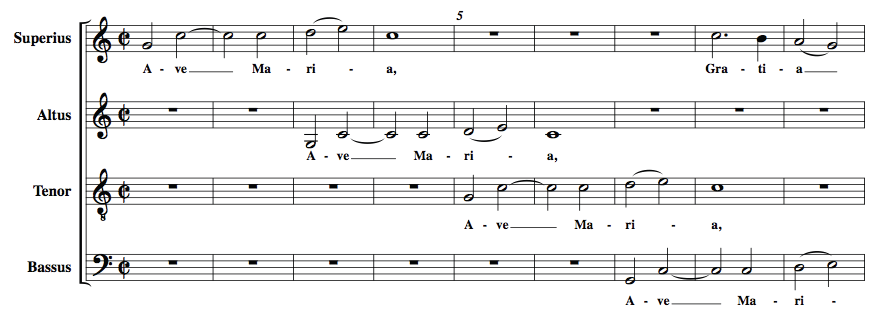

Josquin’s “Ave Maria …Virgo Serena”(“Hail, Mary … Serene Virgin”) ca. 1485 is an outstanding Renaissance choral work. A four-part (Soprano, Alto, Tenor, Bass) Latin prayer, the piece weaves one, two, three, and four voices at different times in polyphonic texture.

Listening Guide: Ave Maria

To view a full text score of Josquin des Prez “Ave Maria…Virgo Serena” while listening.

- Composer: Josquin des Prez

- Composition: Ave Maria…Virgo Serena

- Date: c. 1485, possibly Josquin’s earliest dated work

- Genre: motet

- Form: through-composed in sections

- Performing Forces: four-part choir

Translation: http://unam-ecclesiam.blogspot.com/2007/10/another-beautiful-ave-ma-ria-by-josquin.html

What we want you to remember about this composition: The piece is revolutionary in how it presents the imitative weaving of melodic lines in polyphony. Each voice imitates or echoes the high voice (soprano).

Other things to listen for: After the initial introduction to Mary, each verse serves as a tribute to the major events of Mary’s life—her conception, the nativity, annunciation, purification, and assumption. See the above translation and listening guide.

Spotlight on Women Composers

Caterina Assandra

A benedictine nun born in Pavia, Italy. Assandra received musical instruction from Benedetto Re at Pavia Cathedral. She took vows in an isolated rural Benedictine monastery, and continued to compose after becoming a nun.

Her opus 1 (probably before 1608) is lost, but two motets, Ave verum corpus, and Ego flos campi, which survive without text in a German organ tablature, are probably from that volume (D-Rtt; ed. C. Johnson: Organ music by Women Composers before 1800, Pullman, WA, 1993).

According to her 1609 dedication to Biglia, she took vows in an ancient but isolated rural Benedictine monastery, shortly after the volume’s publication (taking ‘Agata’ as her religious name).

She seems to have continued to compose after her profession: an imitative eight-voice Salve Regina appeared in Re’s Vespers collection of 1611, and a motet, Audite verbum Dominum, for four voices was included in his motet book of 1618.

The 18 small-scale motets (plus two works by Re) include both highly traditional pieces (e.g. O salutaris hostia, for two voices, and two instruments of a simple double-choir motet) and more innovative works.

Among the latter is Duo seraphim (ed. B.G. Jackson, Fayetteville, AK, 1990), in which a change in mode reflects the Apocalyptic text; some of the features of this piece anticipate Monteverdi’s setting of the same text in 1610. A portion of this work can be heard here: Caterina Assandra : Duo seraphim (Live in Sablé – I Gemelli)

Music of Catholicism—Renaissance Mass

In the sixteenth century, Italian composers excelled with works comparable to the mastery of Josquin des Prez and his other contemporaries. One of the most important Italian Renaissance composers was Giovanni Pieruigi da Palestrina (c. 1525-1594). Devoting his career to the music of the Catholic Church, Palestrina served as music director at St. Peter’s Cathedral, and composed 450 sacred works and 104 masses. His influence in music history is best understood with a brief background of the Counter-Reformation.

Protestant reformists like Martin Luther and others sought to correct malpractices and abuses within the structure of the Catholic Church. The Reformation began with Martin Luther and spread to two more main branches: The Calvinist and The Church of England. The protestant reformists challenged many practices that benefited only the church itself and did not appear to serve the lay members (parishioners). A movement occurred within the church to counter the protestant reformation and preserve the original Catholic Church. The preservation movement or “Counter-Reformation” against the protestant reform led to the development of the Jesuit order (1540) and the later assembling of the Council of Trent (1545-1563) which considered issues of the church’s authority and organizational structure. The Council of Trent also demanded simplicity in music so that the words might be heard clearly.

The Council of Trent discussed and studied the many issues facing the Catholic Church, including the church’s music. The papal leadership felt that the music had gotten so embellished and artistic that it had lost its purity and original meaning. It was neither easily sung nor were its words (still in Latin) understood. Many accused the types of music in the church of being theatrical and more entertaining rather than a way of worship (something that is still debated in many churches today). The Council of Trent felt melodies were secular, too ornamental, and even took dance music as their origin. The advanced weaving of polyphonic lines could not be understood, thereby detracting from their original intent of worship with the sacred text. The Council of Trent wanted a paradigm shift of religious sacred music back toward monophonic Gregorian chant. The Council of Trent finally decreed that church music should be composed to inspire religious contemplation and not just give empty pleasure to the ear of the worshiper.

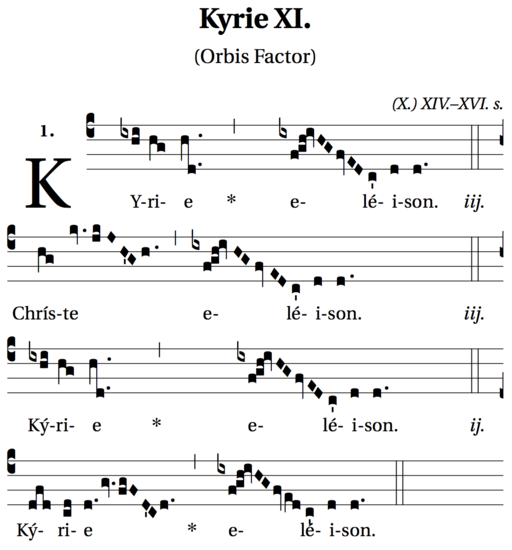

Renaissance composer Palestrina heeded the recommendations from The Council of Trent and composed one of the period’s most famous works, “Missa Papae Marcelli” (Pope Marcellus Mass). Palestrina’s restraint and serenity reflect the recommendations of The Council of Trent. The text, though quite polyphonic, is easily understood. The movement of the voices does not distract from the sacred meaning of the text. Throughout history, Palestrina’s works have been the standard for their calmness and quality.

Listening Guide: Missa Papae Marcelli – I. Kyrie

- Composer: Giovanni Pierluigi da Palestrina (1525-1594)

- Composition: “Missa Papae Marcelli” (Pope Marcellus Mass)- 1. Kyrie

- Date: c. 1562

- Genre: Choral, Kyrie of Mass

- Form: through-composed (without repetition in the form of verses, stanzas, or strophes) in sections

- Performing Forces: Unknown vocal ensemble

Nature of Text:

| Greek Text | English Translation |

| Kyrie eleison | Lord have mercy |

| Christe eleison | Christ have merce |

| Kyrie eleison | Lord have mercy |

What we want you to remember about this composition: Listen to the polyphony and how the voices move predominantly stepwise after a leap upward. After an initial voice begins the piece, the other voices enter, imitating the initial melody and then continue to weave the voices as more enter. Palestrina’s mass would come to represent proper counterpoint/polyphony and become the standard for years to come.

Other things to listen for: Even though the voices overlap in polyphony, the text is easily understood. The masses were written so as to bring out the text and make it simple to understand. The significance of the text is brought out and easily understood.

Musical Score:

Music of the Protestant Reformation

As a result of the Reformation, congregations began singing strophic hymns in German with stepwise melodies during their worship services. This practice enabled the full participation of worshipers. Full participation of the congregations’ members further empowered the individual church participant, thus contributing to the Renaissance’s Humanist movement. Early Protestant hymns stripped away contrapuntal textures, utilized regular beat patterns, and set biblical texts in German.

Instead of a worship service being led with a limited number of clerics at the front of the church, Luther wanted the congregation to actively and fully participate, including in the singing of the service. Since these hymns were in German, members of the parish could sing and understand them. Luther, himself a composer, composed many hymns and chorales to be sung by the congregation during worship, many of which Johann Sebastian Bach would make the melodic themes of his Chorale Preludes 125 years after the original hymns were written. These hymns are strophic (repeated verses as in poetry) with repeated melodies for the different verses. Many of these chorales utilize syncopated rhythms to clarify the text and its flow (rhythms). Luther’s hymn “A Mighty Fortress” is a good example of this practice. The chorales/hymns were usually in four parts and moved with homophonic texture (all parts changing notes in the same rhythm). The melodies of these four-part hymn/chorales used as the basis for many chorale preludes performed on organs prior to and after worship services are still used today.

An example of one such Chorale Prelude based on Luther’s hymn can be found at:

Listening Guide: A Mighty Fortress is Our God

- Composer: Martin Luther

- Composition: “A Mighty Fortress Is Our God” (also known as the “Battle Hymn of the Reformation”)

- Date: 1529

- Genre: Four-Part homophonic church anthem. This piece was written to be sung by the lay church membership instead of just by the church leaders as was practiced prior to the Reformation.

- Form: Four-part Chorale, Strophic

- Performing Forces: Congregation-This recording is the Choir of First Plymouth Church, Lincoln Nebraska

Things to listen for: stepwise melody and syncopated rhythms centered around text

Nature of Text: Originally in German so it could be sung by all church attendees.

Translation:

Translated from original German to English by Frederic H. Hedge in 1853.

A mighty fortress is our God, a bulwark never failing;

Our helper He, amid the flood of mortal ills prevailing:

For still our ancient foe doth seek to work us woe;

His craft and power are great, and, armed with cruel hate,

On earth is not his equal.

Did we in our own strength confide, our striving would be losing;

Were not the right Man on our side, the Man of God’s own choosing:

Dost ask who that may be? Christ Jesus, it is He;

Lord Sabaoth, His Name, from age to age the same, And He must win the battle.

And though this world, with devils filled, should threaten to undo us,

We will not fear, for God hath willed His truth to triumph through us:

The Prince of Darkness grim, we tremble not for him;

His rage we can endure, for lo, his doom is sure, One little word shall fell him.

That word above all earthly powers, no thanks to them, abideth;

The Spirit and the gifts are ours through Him Who with us sideth:

Let goods and kindred go, this mortal life also;

The body they may kill: God’s truth abideth still,

His kingdom is forever.

This recording is in English and performed by the Choir of First Plymouth Church, Lincoln Nebraska.

Secular Music: Entertainment Music of The Renaissance

Royalty sought the finest of the composers to employ for entertainment. A single court, or royal family, could employ as many as ten to sixty musicians, singers, and instrumentalists. In Italy, talented women vocalists began to serve as soloists in the courts.

Secular pieces for the entertainment of nobility and sacred pieces for the chapel were composed by the court music directors. Musicians were often transported from one castle to another to entertain the court’s patron, traveling in their patron’s entourage.

The Renaissance town musicians performed for civic functions, weddings, socials, and religious ceremonies/services. Due to the market, that is, the supply and demand of the expanding Renaissance society, musicians experienced higher status and pay unlike ever before. The Flanders, Low Countries of the Netherlands, Belgium, and northern France became a source of musicians who filled many important music positions in Italy. As in the previous era, vocal music maintained its important status over instrumental music.

Germany, England, and Spain also experienced an energetic musical expansion. Secular vocal music became increasingly popular during the Renaissance. In Europe, music was set to poems from several languages, including English, French, Dutch, German, and Spanish. The invention of the printing press led to the publication of thousands of collections of songs that were never before available. One instrument or small groups of instruments were used to accompany solo voices or groups of solo voices.

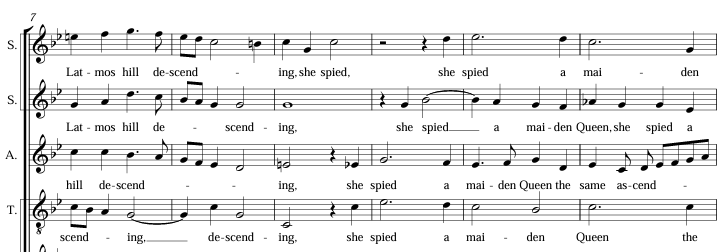

Thomas Weelkes

Thomas Weelkes, a church organist and composer, became one of the finest English madrigal composers. Thomas Weelkes’ “As Vesta Was Descending” serves as a good example of word painting with the melodic line following the meaning of the text in performance.

Listening Guide: As Vesta Was From Latmos Hill Descending

- Composer: Thomas Weelkes

- Composition: “As Vesta Was From Latmos Hill Descending”

- Date: 1601

- Genre: Madrigal

- Form: Through-composed

- Performing Forces: Choral ensemble

One thing to remember about this composition:

This composition is a great example of “word painting” where the text and melodic line work together. When the text refers to descending down a hill, the melody descends also.

| Timing | Performing Forces, Melody, and Texture | Text and Form |

| 0:00 | Descending melodic/scales on “descending” | As Vesta was from Latmos hill descending |

| 0:14 | Ascending melodic/scales on “ascending” | she spied a maiden queen the same ascending |

| 0:31 | Melody gently undulates, neither ascending nor descending | attended on by all the shepherds swain, |

| 0:45 | Rapid imitative descending figures on running down | to whom Diana’s darlings came running down. |

| 1:05 | Two voices, three voices, and then all voices | First two by two, then three by three together, |

| 1:12 | solo voice or unison | leaving their goddess all alone, hasted thither |

| 1:24 | All voices in delicate polyphony | and mingling with the shepherds of her train with mirthful tunes her presence entertains |

| 1:40 | All voices unite to introduce the final proclamation | Then sang the shepherds and nymphs of Diana, |

| 1:52 | Brief, joyful phrase imitated among voices is repeated over and over | Long live fair Oriana! |

Renaissance Dance Music

With the rebirth of the Renaissance came a resurgence of the popularity of dance. This resurgence led to instrumental dance music becoming the most widespread genre for instrumental music. Detailed instruction books for dance also included step orders and sequences that followed the music accompaniment.

The first dances started similar to today’s square dances, but soon evolved into more elaborate and unique forms of expression. Examples of three types of Renaissance dances include the pavanne, galliard, and jig. Video examples of each type of dance are linked with their definitions.

The pavanne is a more solemn stately dance in a duple meter (in twos). Its participants dance and move around with prearranged stopping and starting places with the music. Pavannes are more formal and used in such settings.

The galliard is usually paired with a pavanne. The galliard is in triple meter (in threes) and provides an alternative to the rhythms of the pavanne.

The jig is a folk dance or its tune in an animated meter. It was originally developed in the 1500s in England. The instrumental jig was a popular dance number. Jigs were regularly performed in Elizabethan theaters after the main play.

William Kemp actor, song-and-dance performer, and comedian is immortalized for having created comic roles in Shakespeare. He accompanied his jig performances with pipe, tabor, and snare drum. Kemp’s jig started a unique phrasing/cadence system that carried well past the Renaissance period.

Listening Guide

- Composer: Composer unknown but was performed by William Kemp. The piece became known as Kemp’s Jig

- Composition: “Kemp’s Jig”

- Date: late 1500s

- Genre: Jig (Dance Piece instrumental)

- Form: abb (repeated in this recording)

- Performing Forces: Lute solo instrumental piece

Most dances of the period had a rhythmic and harmony pause or repose (cadence) every four or eight measures to mark a musical or dancing phrase.

What we want you to remember about this composition:

A jig is a light folk dance. It is a dance piece of music that can stand alone when played as an instrumental player. This new shift in instrumental music from strictly accompaniment to stand alone music performances begins a major advance for instrumental music.

Will Kemp was a dancer and actor. He won a bet that he could dance from London to Norwich (80 miles). “Kemps Jig” was written to celebrate the event.

One thing to remember about this composition:

This piece of dance music is evolving from just a predictable dance accompaniment to a central piece of instrumental music. Such alterations of dance music for the sake of the music itself are referred to as the stylization of dance music that has carried on through the centuries.

To view an informative Renaissance Music Timeline.

Chapter Summary

The Renaissance period was truly a time of great discovery in science, music, society, and the visual arts. The re-emergence and renewed interest in Greek and Roman history/culture is still current in today’s modern society. Performing music outside of the church in courts and the public really began to thrive in the Renaissance and continues today in the music industry. Many of the masterworks, both sacred and secular, from the Renaissance are still appreciated and continue to be the standard for today’s music industry. Songs of love, similar to Renaissance chansons, are still composed and performed today. The beauty of Renaissance music, as well as the other arts, is reintroduced and appreciated in modern-day theater performances and visually in museums. The results of the Protestant Reformation are still felt today, and the struggles between contemporary and traditional church worship continues very much as it did during the Renaissance. As we continue our reading and study of music through the Baroque period, try to recall the changes and trends of the Medieval and Renaissance eras and how they thread their way through history to today. Music and the Arts do not just occur; they evolve and also remain the same.

Glossary

- Anthem – a musical composition of celebration, usually used as a symbol for a distinct group, particularly the national anthems of countries. Originally, and in music theory and religious contexts, it also refers more particularly to short sacred choral work and still more particularly to a specific form of Anglican choral music.

- Church Music – Sacred music written for performance in church, or any musical setting of ecclesiastical liturgy, or music set to words expressing propositions of a sacred nature, such as a hymn. Church Music Director is a position responsible for the musical aspects of the church’s activities.

- Chanson – is in general any lyric-driven French song, usually polyphonic and secular. A singer specializing in chansons is known as a “chanteur” (male) or “chanteuse” (female); a collection of chansons, especially from the late Middle Ages and Renaissance, is also known as a chansonnier.

- Chapel Master – Director of music, secular and sacred, for the courts’ official functions and entertainment.

- Consort – A renaissance consort is a group of renaissance instrumentalists playing together. A whole consort is an ensemble performing with instruments from the same family. A broken consort is an ensemble composed of instruments from more than one family.

- Counter-Reformation – The preservation movement or “Counter-Reformation” against the Protestant reform led to the development of the Jesuit order (1540) and the later calling of the Council of Trent (1545-1563), which considered issues of the church’s authority and organizational structure.

- Dance Music [WM1] – is music composed specifically to facilitate or accompany dancing

- Frets – is a raised strip on the neck of a stringed instrument. Frets usually extend across the full width of the neck and divide the string into half steps for most Western musical instruments. Most guitars have frets.

- Galliard – was a form of Renaissance dance and music popular all over Europe in the 16th century.

- Jig – is the accompanying dance tune for an energetic folk dance usually in a compound meter.

- Madrigal – a musical piece for several solo voices set to a short poem. They originated in Italy around 1520. Most madrigals were about love.

- Motet – is a highly varied sacred choral musical composition. The motet was one of the pre-eminent polyphonic forms of Renaissance music.

- Pavanne – is a slow processional dance common in Europe during the 16th century Renaissance.

- Reformation – was a secession and division from the practices of the Roman Catholic Church initiated by Martin Luther. Led to the development of Protestant churches.

- Word painting – was utilized by Renaissance composers to represent poetic images musically. For example, an ascending melodic line would portray the text “ascension to heaven.” Or a series of rapid notes would represent running.

This chapter adapted from Understanding Music Past and Present By Jeff Kluball; edited and adapted by Amy McGlothlin

Media Attributions

- The School of Athens © Raphael via. Wikipedia is licensed under a Public Domain license

- David Fighting Goliath © Met Museum is licensed under a Public Domain license

- Michelangelo’s rendition of David © Wikipedia is licensed under a Public Domain license

- Madonna (1280) © Wikipedia is licensed under a Public Domain license

- Giotto’s Madonna (1310) © Wikipedia is licensed under a Public Domain license

- Raphael’s Madonna (1504) © Wikipedia is licensed under a Public Domain license

- Wittenberg Church © User “Fewskulcho” via. Wikipedia is licensed under a Public Domain license

- Opening Line of Ave Maria © Josquin Des Prez via. Wikipedia is licensed under a Public Domain license

- Musical score of “Kyrie” opening © Micah Walter via. Wikipedia is licensed under a CC BY-SA (Attribution ShareAlike) license

- Examples of “word painting” in Weelkes’s “As Vesta Was From Latmos Hill Descending” © ChoralWiki is licensed under a CC0 (Creative Commons Zero) license