2.2 Mass Media Growth and Consolidation

Learning Objectives

- Explore the historical development of mass media, including the rise of brand advertising, professional journalism, digital networks, and various forms of convergence, to understand how they have shaped media consumption, production, and the fragmentation of mass audiences.

- Investigate the ethical dilemmas in journalism, such as autonomy versus social responsibility, and critically evaluate practices like objectivity and the influence of hyper-partisan media environments to understand the role of media organizations in societal repercussions.

- Analyze the effects of digital media on societal structures and cultural production, including democratization, filter bubbles, de-massification, gatekeeping, and convergence, to understand both positive and negative implications for society, cognition, and individual engagement with media.

As mass production of all sorts of manufactured goods grew during the 20th century, so did advertising budgets and the concept of brands. Brand advertising became fuel for the mass media, and as profitability rose, newspapers were bought up and organized into chains throughout the 20th century. Many newspapers grew their audience as they merged.

Partisan papers gave way to a brand of news that strived for objectivity. The profit motive mostly drove the change. To attract a mass audience, newspapers had to represent various points of view. This pushed some of the most opinionated citizens, particularly strong advocates for workers, to the fringes of mass discourse. Some advocates developed alternative media offerings. Others went mostly unheard or plied their craft directly in politics.

At the same, throughout much of the 20th century, the journalism workforce became more professionalized. Professional norms, that is the written and unwritten rules guiding behavior decided on by people in a given field, evolved. Many full-time, paid professional journalists stressed and continue to stress the need to remain detached from the people they cover so that journalists can maintain the practice and appearance of objectivity. Journalists emphasized objectivity in order to remain autonomous and to be perceived as truthful. The norm of objective reporting still strongly influences news coverage in newspapers as well as on most mainstream radio and television news networks.

That being said, the practice of maintaining objectivity is being called into question in our current hyper-partisan political media environment. Other strategies for demonstrating truthfulness require journalists to be transparent about how they do their work, about who owns their media outlets, and about what investments and personal views they may have. Chapter 9 covers news norms and their evolution in greater detail.

At the heart of the ethical discussion for professional journalists is a sort of battle between the need to be autonomous to cover news accurately with minimal bias and the need to be socially responsible. Social responsibility in the study of journalism ethics is a specific concept referring to the need for media organizations to be responsible for the possible repercussions of the news they produce. The debate goes on even as more and more platforms for mass communication are developed.

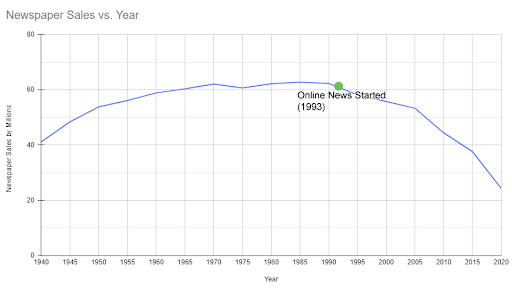

Beyond advancements in ink-on-paper newspapers (including the development of color offset printing), technological developments have contributed to the diversification of mass media products. Photography evolved throughout the 20th century, as did motion picture film, radio, and television technology. Other mass media presented challenges and competition for newspapers. Still, newspapers were quite a profitable business. They grew to their greatest readership levels in the middle-to-late 20th century, and their value was at its high point around the turn of the 21st century. Then came the Internet.

Digital Media: Collaboration and Conflict

With the rise of global computer networks, particularly high-speed broadband and mobile communication technologies, individuals gained the ability to publish their own work and to comment on mass media messages more easily than ever before. If mass communication in the 20th century was best characterized as a one-to-many system where publishers and broadcasters reached waiting audiences, the mass media made possible by digital information networks in the 21st century have taken on a many-to-many format.

For example, YouTube has millions of producers who themselves are also consumers. None of the social media giants such as Facebook, YouTube, Instagram, Qzone, Weibo (in China), Twitter, Reddit, or Pinterest is primarily known for producing content. Instead, they provide platforms for users to submit their own content and to share what mass media news and entertainment companies produce. The result is that the process of deciding what people should be interested in is much more decentralized in the digital network mass media environment than it was in the days of an analog one-to-many mass media system.

The process of making meaning in society — that is, the process of telling many smaller stories that add up to a narrative shared by mass audiences — is now much more collaborative than it was in the 20th century because more people are consuming news in networked platforms than through the channels managed by gatekeepers. A mass media gatekeeper is someone, professional or not, who decides what information to share with mass audiences and what information to leave out.

Fiction or non-fiction, every story leaves something out, and the same is true for shows made up of several stories, such as news broadcasts and heavily edited reality television. Gatekeepers select what mass audiences see and then edit or disregard the rest. The power of gatekeepers may be diminished in networks where people can decide for themselves what topics they care most about. However, there is still an important gatekeeping function in the mass media since much of what is ultimately shared on social media platforms originates in the offices and studios of major media corporations.

On social media platforms, media consumers have the ability to add their input and criticism, and this is an important function for users. Not only do we have a say as audience members in the content we would like to see, read, and hear, but we also have an important role to play in society as voting citizens holding their elected officials accountable.

If social media platforms were only filled with mass media content, individual user comments, and their own homegrown content, digitally networked communication would be complex enough, but there are other forces at work. Rogue individuals, hacker networks, and botnets — computers programmed to create false social media accounts, websites, and other digital properties — can contribute content alongside messages produced by professionals and legitimate online community members. False presences on social media channels can amplify hate and misinformation and can stoke animosity between groups in a hyper-partisan media age.

Around the world, societies have democratized mass communication, but in many ways, agreeing on a shared narrative or even a shared list of facts is more difficult than ever. Users create filter bubbles for themselves where they mostly hear the voices and information that they want to hear. This has the potential to create opposing worldviews where users with different viewpoints not only have differing opinions, but they also have in mind completely different sets of facts creating different images about what is happening in the world and how society should operate.

When users feel the need to defend their filtered worldviews, it is quite harmful to society.

De-massification

The infiltration of bots on common platforms is one issue challenging people working in good faith to produce accurate and entertaining content and to make meaning in the mass media. De-massification is another. Professionals working on mass-market media products now must fight to hold onto mass audiences. De-massification signifies the breakdown of mass media audiences. As the amount of information being produced and the number of channels on which news and other content can be disseminated grows exponentially, ready-made audiences are in decline.

In the future, it is anticipated that audiences, or fan bases, must be built rather than tapped into. One path to growing audiences in digital networks is to take an extreme point of view. Producers of news and entertainment information on the right and left of the political spectrum often rail against mainstream media as they promote points of view that are more or less biased. This kind of polarization, along with the tendency of social media platforms to allow and even encourage people to organize along political lines, likely contributes to de-massification as people organize into factions. This practice, while clearly effective, has incredibly damaging side effects. These methods of growing audiences encourage very violent and vitriolic interactions online and lead to a pipeline of extremism and radicalism that can grow into real-world headlines. This is concerning as those responsible for raising such audiences rarely- if ever- face consequences for what behaviors they grow and perpetuate[1].

The future of some mass communication channels as regular providers of shared meaning for very large audiences is in question. That said, claims that any specific medium is “dead” are overblown. For example, newspaper readership, advertising revenue, and employment numbers have been declining for about 25 years, but as of 2020, there are still more than 25 million newspaper subscribers[2]. Mass audiences are shrinking and shifting, but they can still be developed.

Convergence

As mass audiences are breaking up and voices from the fringe are garnering outsized influence, the various types of media (audio, video, text, animation and the industries they are tied to) have come together on global computer and mobile network platforms in a process called convergence.

It is as though all media content is being tossed into a huge stew, one that surrounds and composes societies and cultures, and within this stew of information, people are re-organizing themselves according to the cultural and social concerns they hold most dear.

According to one hypothesis, in a society dominated by digital communication networks, people gather around the information they recognize and want to believe because making sense of the vast amount of information now available is impossible.

This text covers several mass media channels, including social media, film, radio, television, music recording and podcasting, digital gaming, news, advertising, public relations, and propaganda because these are still viable industries even as the content they produce appears more and more often on converged media platforms.

What we see emerging in networked spaces is a single mass media channel with a spectrum of possible text, photo, audio, video, graphic, and game elements; however, the sites of professional production still mostly identify as one particular industry (such as radio and recorded music, film, television, cable television, advertising, PR, digital advertising or social media). Some of these are “legacy” media that have existed as analog industries prior to convergence, while others originated in digital media environments.

For the foreseeable future, we should expect legacy media producers to continue to hold formidable power as elements of larger media conglomerates, which acquired many media companies as a result of industry deregulation. We should also expect audiences to continue to fragment and digital media start-ups try to build audiences out of fragmented communities to be common even if they are difficult to sustain.

What this means for social structures and for cultural production is disruption, limited perhaps by legacy media traditions and corporate power.

It’s important to keep in mind that the implementation of new technologies doesn’t mean that the old ones simply vanish into dusty museums. Today’s media consumers still watch television, listen to radio, read newspapers, and become immersed in movies. The difference is that it’s now possible to do all those things through one device—be it a personal computer or a smartphone—and through the Internet. Such actions are enabled by media convergence, the process by which previously distinct technologies come to share tasks and resources. A cell phone that also takes pictures and videos is an example of the convergence of digital photography, digital video, and cellular telephone technologies. An extreme and currently nonexistent example of technological convergence would be the so-called black box, which would combine all the functions of previously distinct technology and would be the device through which we’d receive all our news, information, entertainment, and social interaction.

Kinds of Convergence

But convergence isn’t just limited to technology. Media theorist Henry Jenkins argues that convergence isn’t an end result (as is the hypothetical black box) but, instead, a process that changes how media is both consumed and produced. Jenkins breaks convergence down into five categories:

- Economic convergence occurs when a company controls several products or services within the same industry. For example, in the entertainment industry, a single company may have interests across many kinds of media. For example, Rupert Murdoch’s News Corporation is involved in book publishing (HarperCollins), newspapers (New York Post, The Wall Street Journal), sports (Colorado Rockies), broadcast television (Fox), cable television (FX, National Geographic Channel), film (20th Century Fox), Internet (MySpace), and many other media.

- Organic convergence is what happens when someone is watching a television show online while exchanging text messages with a friend and also listening to music in the background—the “natural” outcome of a diverse media world.

- Cultural convergence has several aspects. Stories flowing across several kinds of media platforms is one component—for example, novels that become television series (True Blood); radio dramas that become comic strips (The Shadow); and even amusement park rides that become film franchises (Pirates of the Caribbean). The character Harry Potter exists in books, films, toys, and amusement park rides. Another aspect of cultural convergence is participatory culture—that is, the way media consumers are able to annotate, comment on, remix, and otherwise influence culture in unprecedented ways. The video-sharing website YouTube is a prime example of participatory culture. YouTube gives anyone with a video camera and an Internet connection the opportunity to communicate with people around the world and create and shape cultural trends.

- Global convergence is the process of geographically distant cultures influencing one another despite the distance that physically separates them. Nigeria’s cinema industry, nicknamed Nollywood, takes its cues from India’s Bollywood, which is in turn inspired by Hollywood in the United States. Tom and Jerry cartoons are popular on Arab satellite television channels. Successful American horror movies like The Ring and The Grudge are remakes of Japanese hits. The advantage of global convergence is access to a wealth of cultural influence; its downside, some critics posit, is the threat of cultural imperialism, defined by Herbert Schiller as the way developing countries are “attracted, pressured, forced, and sometimes bribed into shaping social institutions to correspond to, or even promote, the values and structures of the dominating center of the system.[3]” Cultural imperialism can be a formal policy or can happen more subtly, as with the spread of outside influence through television, movies, and other cultural projects.

- Technological convergence is the merging of technologies, such as the ability to watch TV shows online on sites like Hulu or to play video games on mobile phones like the Apple iPhone. When more and more different kinds of media are transformed into digital content, as Jenkins notes, “we expand the potential relationships between them and enable them to flow across platforms.”

Effects of Convergence

Jenkins’s concept of organic convergence is perhaps the most telling. To many people, especially those who grew up in a world dominated by so-called old media, there is nothing organic about today’s media-dominated world. As a New York Times editorial recently opined, “Few objects on the planet are farther removed from nature—less, say, like a rock or an insect—than a glass and stainless steel smartphone.”[4] But modern American culture is plugged in as never before, and today’s high school students have never known a world where the Internet didn’t exist. Such a cultural sea change causes a significant generation gap between those who grew up with new media and those who didn’t.

A 2010 study by the Kaiser Family Foundation found that Americans aged 8 to 18 spend more than 7.5 hours with electronic devices each day—and, thanks to multitasking, they’re able to pack an average of 11 hours of media content into that 7.5 hours.[5] These statistics highlight some of the aspects of the new digital model of media consumption: participation and multitasking. Today’s teenagers aren’t passively sitting in front of screens, quietly absorbing information. Instead, they are sending text messages to friends, linking news articles on Facebook, commenting on YouTube videos, writing reviews of television episodes to post online, and generally engaging with the culture they consume. Convergence has also made multitasking much easier, as many devices allow users to surf the Internet, listen to music, watch videos, play games, and reply to e-mails on the same machine.

However, it’s still difficult to predict how media convergence and immersion are affecting culture, society, and individual brains. In his 2005 book Everything Bad Is Good for You, Steven Johnson argues that today’s television and video games are mentally stimulating in that they pose a cognitive challenge and invite active engagement and problem-solving. Poking fun at alarmists who see every new technology as making children stupider, Johnson jokingly cautions readers against the dangers of book reading: It “chronically understimulates the senses” and is “tragically isolating.” Even worse, books “follow a fixed linear path. You can’t control their narratives in any fashion—you simply sit back and have the story dictated to you… This risks instilling a general passivity in our children, making them feel as though they’re powerless to change their circumstances. Reading is not an active, participatory process; it’s a submissive one.”[6]

A 2010 book by Nicholas Carr, The Shallows: What the Internet Is Doing to Our Brains, is more pessimistic. Carr worries that the vast array of interlinked information available through the Internet is eroding attention spans and making contemporary minds distracted and less capable of deep, thoughtful engagement with complex ideas and arguments. “Once I was a scuba diver in a sea of words,” Carr reflects ruefully. “Now I zip along the surface like a guy on a Jet Ski.”[7] Carr cites neuroscience studies showing that when people try to do two things at once, they give less attention to each and perform the tasks less carefully. In other words, multitasking makes us do a greater number of things poorly. Whatever the ultimate cognitive, social, or technological results, convergence is changing the way we relate to media today.

Video Killed the Radio Star: Convergence Kills Off Obsolete Technology—or Does It?

When was the last time you used a rotary phone? How about a street-side pay phone? Or a library’s card catalog? When you need brief, factual information, when was the last time you reached for a volume of Encyclopedia Britannica? Odds are it’s been a while. All of these habits, formerly common parts of daily life, have been rendered essentially obsolete through the progression of convergence.

But convergence hasn’t erased old technologies; instead, it may have just altered the way we use them. Take cassette tapes and Polaroid film, for example. Influential musician Thurston Moore of the band Sonic Youth recently claimed that he only listens to music on cassette. Polaroid Corporation, creators of the once-popular instant-film cameras, was driven out of business by digital photography in 2008, only to be revived 2 years later—with pop star Lady Gaga as the brand’s creative director. Several Apple iPhone apps allow users to apply effects to photos to make them look more like a Polaroid photo.

Cassettes, Polaroid cameras, and other seemingly obsolete technologies have been able to thrive—albeit in niche markets—both despite and because of Internet culture. Instead of being slick and digitized, cassette tapes and Polaroid photos are physical objects that are made more accessible and more human, according to enthusiasts, because of their flaws. “I think there’s a group of people—fans and artists alike—out there to whom music is more than just a file on your computer, more than just a folder of MP3s,” says Brad Rose, founder of a Tulsa, Oklahoma-based cassette label (Hogan, 2010). The distinctive Polaroid look—caused by uneven color saturation, underdevelopment or overdevelopment, or just daily atmospheric effects on the developing photograph—is emphatically analog. In an age of high-resolution, portable printers, and camera phones, the Polaroid’s appeal to some has something to do with ideas of nostalgia and authenticity. Convergence has transformed who uses these media and for what purposes, but it hasn’t eliminated them.

Melding Theories

The world of mass media has witnessed the convergence of media content on digital platforms, the ability of individuals to engage in one-to-many communication as though they were major broadcasters, and the emergence of structures that allow for many-to-many communication. These developments force us to rethink how separate interpersonal, organizational, and mass communication truly are.

From a theoretical standpoint, these are well-established approaches to thinking about communication, but in practice, certain messages might fit into multiple categories. For example, a YouTube video made for a few friends might reach millions if it goes viral. Is it interpersonal communication, mass communication, or both? Viral videos and memes spread to vast numbers of people but might start out as in-jokes between internet friends or trolls. The message’s original meaning is often lost in this process. In a networked society, it can be difficult to differentiate between interpersonal and mass communication. For our purposes, it will be helpful to consider the message creator’s intent.

As a user, it is essential to realize the possibility that interpersonal messages may be shared widely. As professionals, it also helps to realize that you cannot force a message to go viral. However, most social media platforms now engage in various kinds of paid promotion where brands and influential users can pay to have their content spread more widely and more quickly.

We must also understand that advertisers treat digital communication platforms much the same way whether they appear to users to be interpersonal or mass media environments. Users can be targeted down to the individual on either type of platform, and advertisers (with the help of platform creators), can access mass audiences, even when users are intending only to participate on a platform for purposes of interpersonal communication.

Scholars are still working to define how these platforms mix aspects of interpersonal and mass communication. Here is one takeaway: If you are not paying to use a platform like Facebook, Twitter, YouTube (Google), Instagram, or Snapchat, you are the product. It is your attention that is being sold to advertisers.

Rise of AI Content

In recent times, the rise of AI software such as ChatGPT and other machine learning algorithms has brought light to an old conspiracy theory called “Dead Internet Theory.”[8] This conspiracy is the belief the majority of the Internet is, in actuality, just machines and bots creating content for actual humans to purchase and consume. While seemingly outlandish, it has been calculated that up to 47% of internet traffic is from bots.[9] What was once considered a conspiracy theory may slowly become true.

This increase in automated content being shared online has made online communication considerably more difficult. For instance, when one searches for an image on Google, Google will try to make an AI-generated image of the searched term.[10] Functions such as this lead to interesting questions about why users may search for images and if it matters whether they are authentic. This increased AI usage could have very negative effects on how the average user interacts with the internet as a whole, as it creates an increasingly confusing and uncanny wasteland of near infinitely artificially generated content.

Some news sites now scrub online forums such as Reddit for headlines and report them.[11] Users who are aware of how such reporting works have been able to trick these sites into reporting on blatantly false information intentionally posted to such forums. If content like this increases in volume, the internet as a whole could become increasingly difficult to use and perhaps make it difficult to determine if one is even communicating with another human.

The Big Picture

Society functions when the mass media work well, and we tend not to think about the technologies or the professionals who make it all possible. Interpersonal communication can function with or without a massive technological apparatus. It is more convenient, though, to be able to text each other. When interpersonal communication breaks down, we have problems in our relationships. When organizational communication breaks down, it creates problems for groups and companies. But when mass communication breaks down, society breaks down.

Key Takeaways

- Twenty-first-century media culture is increasingly marked by convergence, or the coming together of previously distinct technologies, as in a cell phone that also allows users to take video and check e-mail.

- Media theorist Henry Jenkins identifies the five kinds of convergence as the following:

- Economic convergence is when a single company has interests across many kinds of media.

- Organic convergence is multimedia multitasking, or the natural outcome of a diverse media world.

- Cultural convergence is when stories flow across several kinds of media platforms and when readers or viewers can comment on, alter, or otherwise talk back to culture.

- Global convergence is when geographically distant cultures are able to influence one another.

- Technological convergence is when different kinds of technology merge. The most extreme example of technological convergence would be one machine that controlled every media function.

- The jury is still out on how these different types of convergence will affect people on an individual and societal level. Some theorists believe that convergence and new-media technologies make people smarter by requiring them to make decisions and interact with the media they’re consuming; others fear the digital age is giving us access to more information but leaving us shallower.

Exercises

Review the viewpoints of Henry Jenkins, Steven Johnson, and Nicholas Carr. Then, answer the following questions. Each response should be a minimum of one paragraph.

- Define convergence as it relates to mass media and provide some examples of convergence you’ve observed in your life.

- Describe the five types of convergence identified by Henry Jenkins and provide an example of each type that you’ve noted in your own experience.

- How do Steven Johnson and Nicholas Carr think convergence is affecting culture and society? Whose argument do you find more compelling and why?

Media Attributions

- Graph Newspaper Sales vs. Year © anonymous student is licensed under a CC BY-NC-SA (Attribution NonCommercial ShareAlike) license

- Nigerian VCDs at kwakoe © Paul Keller via. Flickr is licensed under a CC BY-SA (Attribution ShareAlike) license

- 21184338981_76caaab48c_c © Pedro Ribeiro Simões via. Flickr is licensed under a CC BY-SA (Attribution ShareAlike) license

- Leitch, Shirley: “Rethinking social media and extremism” ANU Press 2022 https://library.oapen.org/viewer/web/viewer.html?file=/bitstream/handle/20.500.12657/58012/book.pdf?sequence=1&isAllowed=y ↵

- McLennan, Douglas, and Jack Miles. “Opinion | A Once Unimaginable Scenario: No More Newspapers.” Washington Post, March 21, 2018. https://www.washingtonpost.com/news/theworldpost/wp/2018/03/21/newspapers/. ↵

- White, Livingston A. “Reconsidering Cultural Imperialism Theory,” TBS Journal 6 (2001), https://web.archive.org/web/20090219225535/http://www.tbsjournal.com/Archives/Spring01/white.html. ↵

- New York Times, editorial, “The Half-Life of Phones,” New York Times, June 18, 2010, http://www.nytimes.com/ 2010/06/20/opinion/20sun4.html1. ↵

- Lewin, Tamar “If Your Kids Are Awake, They’re Probably Online,” New York Times, January 20, 2010, http://www.nytimes.com/2010/01/20/education/20wired.html. ↵

- Johnson, Steven Everything Bad Is Good for You (Riverhead, NY: Riverhead Books, 2005). ↵

- Carr, Nicholas The Shallows: What the Internet Is Doing to Our Brains (New York: Norton, 2010). ↵

- Hughes, Neil: “Echoes of the dead internet theory: AI’s silent takeover” Cybernews August 2023 https://cybernews.com/editorial/dead-internet-theory-ai-silent-takeover/ ↵

- Imperva: “2023 Bad Bot Report” 2023 https://www.imperva.com/resources/reports/2023-Imperva-Bad-Bot-Report.pdf ↵

- Hutchinson, Andew: “Google Adds Generative AI Image Creation into Search” SocialMediaToday October 12 2023 https://www.socialmediatoday.com/news/google-generative-ai-image-creation-search/696511/ ↵

- Luna, Elizabeth: “Reddit tricks an AI into writing an article about a fake World of Warcraft character” Mashable July 21, 2023 https://mashable.com/article/world-of-warcraft-wow-reddit-ai-glorbo ↵