8.2 Impacts of the Telegraph

Learning Objectives

- Articulate the complex interplay of technological, human, and geopolitical factors that shape the materiality and functionality of undersea cables, including their historical roots in telegraph technology.

- Understand the concept of “technogenesis,” and how it applies to the co-evolutionary relationship between humans and communication technologies, from telegraph code books to modern digital networks.

- Gain insights into the notion of “chronocentricity,” enabling them to critically evaluate the perceived uniqueness of contemporary communication technologies by comparing them with historical technologies like the telegraph.

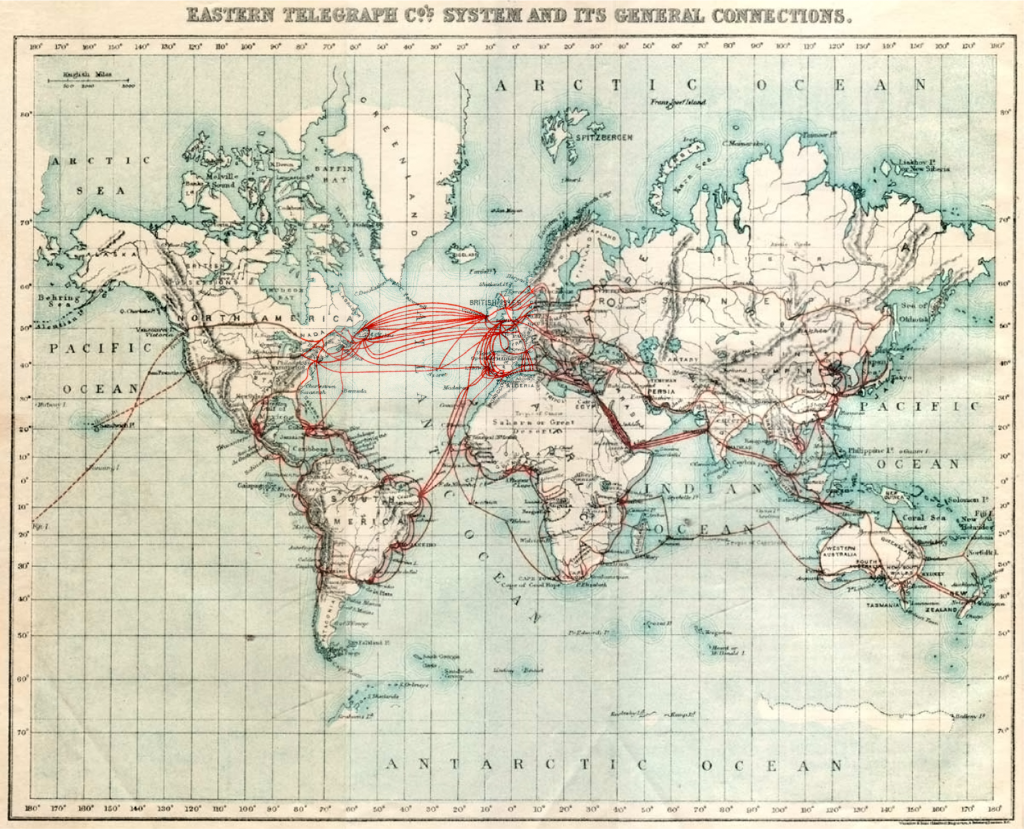

Media Materiality

In today’s digital age, the undersea network of cables serves as the backbone of our global communications, a complex system shaped by technological, human, and geopolitical factors. Nicole Starosielski explores this system in her book, The Undersea Network (Sign, Storage, Transmission), summarized here.[1] Contrary to popular belief, it’s not satellites but these submarine systems that carry the bulk of the Internet across oceans. However, the existence of today’s cables harken back to the era of the telegraph, often still following the same routes due to the complexity of securing the initial rights to lay these cables. These cables, often only 15-20 millimeters thick despite appearing miles wide on maps, are far more than mere technological conduits. They connect to cable stations that serve as critical nodes in both domestic and international networks, and these stations are geopolitical hotspots where governments wield significant control over rates, taxes, and services.

A historical example that encapsulates many of these elements is the cable station in Orleans, Massachusetts. Known as “Le Direct,” this station was the American termination point for a telegraph cable that stretched almost 3,200 miles from Brest, France. Installed in 1898, it was part of a lineage of French cables, the first of which was laid in 1869 and landed in Duxbury, Massachusetts. Duxbury proved to be an unsuitable location due to frequent damage from fishing and shipping operations. A subsequent cable was laid in 1879 to North Eastham, an isolated area that was difficult to reach in bad weather. The current Orleans building was constructed in 1891, and it remained operational until 1959, with a brief closure from 1940 to 1952 during WWII for security reasons. In 1972, the station was purchased from France by a committee of 10 prominent Orleans citizens. They raised money and guaranteed a loan with their personal assets to eliminate the debt, opening the station to the public in July of that year. This example illustrates the complex interplay of technological, human, and geopolitical factors that shape the materiality of undersea cables.[2] Similarly, O‘ahu’s cable landings have turned Hawai‘i into a crucial node in global telecommunications, but they have also led to the displacement of local residents and the creation of makeshift tent cities along the coast.

The human element in these stations has evolved over time. In the early days, operators were integral to the system, literally becoming part of the circuit. Technological advancements have since reduced the human role, but the operation of these stations continues to be shaped by human social practices. Security measures have also evolved, moving from physical fortifications to a focus on actionable knowledge like keystrokes and login codes. In the United States, for instance, cable stations often look like “special fortified bunkers,” but they might be staffed part-time or not at all.

The process of establishing these stations is fraught with challenges, including a cumbersome and expensive permitting process. Landing the Honotua cable in Hawaii required over twenty permits, while Tahiti needed only two. Despite these hurdles, hundreds of thousands of pounds are spent annually on repairs due to trawler damage, a fishing method that drags nets along the seafloor. To mitigate this, committees have suggested making fishing gear safer for cables and implementing government inspections.

As we become increasingly dependent on digital networks, understanding the materiality of undersea cables isn’t just an academic exercise but a necessity for the security and functionality of our interconnected world. The balance of power has shifted in recent years, with updated laws increasing penalties for damaging cables and even transferring money to the fishing industry to allow for cable laying. In some countries, military cables are kept hidden and unmarked, and disruptions are simply allowed to occur.

In network theory, the term “edge” aptly describes the link between two nodes, such as Hawai‘i and Tahiti. These edges are shaped by deliberate manipulations of politics, culture, and the environment. The U.S. Defense Department, for instance, has secured dedicated backup circuits to Canada and Australia in exchange for connections at Hawai‘i, serving various geopolitical interests, including those of high-frequency traders and nations wishing to bypass U.S. surveillance.

The undersea network is a living, evolving entity that impacts not just how we communicate, but also how we live, govern, and engage with the world. By examining the material and immaterial aspects of these networks, we can better appreciate the “physicality of the virtual,” shedding light on the often-invisible forces that shape our global connectivity.

Starosielski also developed a companion website to her Undersea Network book that explores the cables from a physical and theoretical perspective. While it feels somewhat disorienting at first glance, it’s well worth exploring: http://surfacing.in/.

Cultural Effects

Communication scholar James Carey renewed interest and cultural analysis of the telegraph with the publication of a chapter on the telegraph in his 1988 book Communication in Culture: Essays in Media and Society.[3] In that essay, he argued that the telegraph, often considered the pioneer among industries rooted in science and engineering, had a transformative impact on various aspects of human life that extended far beyond the technological realm. Its influence permeated the fabric of language, economics, ideology, and even human consciousness. One of its most groundbreaking contributions was the decoupling of communication from transportation. Before the advent of the telegraph, the concept of “communication” was inextricably linked to physical transportation. Messages had to be carried by foot, horseback (as in the Pony Express, above), or trail from one location to another. The telegraph shattered this paradigm, allowing for the rapid dissemination of information independent of physical entities. This not only accelerated the speed of communication but also served as a control mechanism for the physical world that had been left behind.

This revolutionary technology also had a profound impact on the nature of business and economic relationships. In the era before the telegraph, business was largely a personal affair. Transactions were conducted between individuals who had personal relationships and often knew each other well. The telegraph changed this by enabling impersonal, long-distance transactions, thereby setting the stage for the rise of monopoly capitalism. It transformed the way business was conducted, making it possible for large corporations to dominate markets and for business relationships to become less personal and more transactional.

It was also, Carey argued, steeped in a complex web of ideological and religious rhetoric. It was often described in terms of what has been called the “technological sublime,” a concept that imbued the telegraph with a sense of divine inspiration. In the discourse of the day, the technology was seen as a miraculous tool for spreading Christianity, capable of transcending the limitations of time and space to bring the Christian message to far-flung corners of the world. This religious and ideological framing was part of a broader middle-class ideology that equated communication and exchange with progress and enlightenment. This “electric sublime” promised to annihilate the barriers of time and space, bringing humanity closer together and overcoming the obstacles of isolation and disconnection.

The telegraph also had a lasting impact on the institutionalization of technological development. It led to the formation of professional engineering societies, specialized research laboratories, and university departments that were dedicated to the advancement of technology. This professionalization of technological development created a new paradigm for innovation, one that was rooted in scientific inquiry and academic research.

Moreover, the telegraph had a profound impact on language and the field of journalism. The need for rapid and efficient communication led to a form of language that was stripped of local idioms and colloquial expressions. This shift moved language closer to what could be termed “scientific language,” a form of expression that was precise, clear, and universally understandable. This transformation also influenced literary styles, most notably in the “cablese” style of writing popularized by Ernest Hemingway, which was characterized by its terse, straightforward prose.

The telegraph’s influence also extended to geopolitics, transforming colonialism into imperialism. Backed by sea power, the telegraph enabled the central authority of an empire to dictate terms to its peripheries, rather than merely responding to events at the margins. This shift in power dynamics had a profound impact on global politics, enabling empires to exert greater control over their colonies.

The British Empire’s rule over India is a prime illustration of how the telegraph turned colonialism into imperialism.[4],[5],[6] Prior to the invention of the telegraph, correspondence between the British colonial government in India and the government in London was laborious and lengthy, frequently lasting weeks or even months. The British government struggled to react quickly to the events in India as a result of this delay, which essentially decentralized power and gave local colonial officers some degree of autonomy.

The invention of the telegraph, however, fundamentally altered this dynamic. The British administration could now impose considerably tighter control over its Indian colony since messages could be sent and received very instantly. For instance, the telegraph was essential during the 1857 Indian Rebellion, also known as the First War of Independence or the Sepoy Mutiny. Thanks in major part to the telegraph connections that had been set up throughout the nation, the British were able to quickly assemble troops and plan a response to the rebellion. The British were likely able to put down the uprising more successfully than they could have without this quick communication.

Furthermore, the telegraph enabled the British to better integrate India into its global economic system. Information about prices of commodities like tea, spices, and cotton could be quickly relayed between London and various Indian cities, allowing for more effective market manipulation and resource extraction. This economic control was another form of imperialism, as it allowed the British to dictate terms not just politically but also economically.

In essence, the telegraph shifted the balance of power, enabling the British Empire to transition from a form of colonialism, where local conditions had a significant influence, to a form of imperialism, where control was centralized and exerted from the metropole. This change had a profound impact on the colony and contributed to shaping modern global politics.

In the realm of economics, the telegraph unified disparate markets by allowing for real-time updates on commodity prices. Before the telegraph, markets were localized, operating independently of each other, with prices determined by local conditions of supply and demand. The telegraph changed this by evening out markets across geographical distances, allowing commodity trading to shift from a focus on spatial differences to temporal fluctuations.

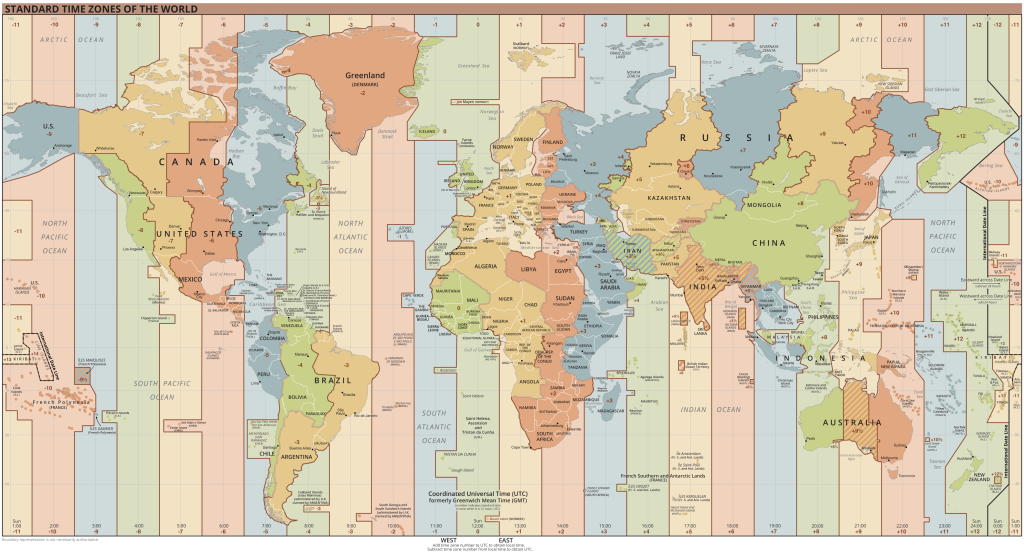

Perhaps one of the most overlooked but significant impacts of the telegraph was its role in the standardization of time. Before the telegraph, local times were determined by the sun reaching its zenith at noon, leading to a plethora of local time zones that caused enormous confusion, especially with the expansion of the railroad system. The telegraph facilitated the creation of standard time zones, which, despite initial resistance on religious and ecological grounds, became essential for coordinating activities and ensuring social control.

Canadian Sanford Fleming was responsible for the implementation of time zones. He served as a chief engineer on the Intercolonial Railway and advocated for the laying of a telegraph cable across the Pacific Ocean to Australia, which he called the “final communication link in the Empire.”[7] Fleming came up with the idea for time zones after missing a train. He then developed the system of the twenty-four hour clock and twenty-four time zones across the globe:

It remained to select a starting point for this system. At the International Prime Meridian Conference in Washington, D.C., in 1884, which Fleming was instrumental in convening, agreement was finally reached aht Greenwich, site of the Royal Observatory in England, would become the 0° and 360° meridian, with a time zone boundary 7° 30’ either side of it, and adjoining zones 15° apart would encircle the globe. It was an elegantly simple system, useful for trains but essential for modern air transportation and instantaneous communication. Canada adopted standard time on 1 January 1885, as did most of the United States, although it did not become law there until 1918. By the end of the nineteenth century most countries subscribed to the system, though the last holdout, Liberia, did not join until 1972.[8]

The telegraph was not merely a technological innovation; it was a cultural and ideological force that reshaped our understanding of language, capitalism, and even time and space. Its far-reaching impacts have affected not just how we communicate but also how we perceive and interact with the world. It revolutionized various facets of human life, from the way we conduct business and express ourselves to how we understand our place in the world and the cosmos.

Technogenesis

The term “technogenesis” was coined by Bernad Steigler. In her book, How We Think: Digital Media and Contemporary Technogenesis, by N. Katherine Hayles, a literary critic and expert in both science and literature, uses the concept to characterize the co-evolutionary relationship between people and technology.[9] Technogenesis, according to Hayles, is the notion that humankind and technology develop side by side in a mutually forming connection. The conventional view that technology is only a tool made and managed by humans is challenged by this idea. Instead, it contends that human evolution, intellect, and culture are all influenced by technology.

Hayles examines how human cognition, social institutions, and even our biological selves have been shaped by technologies like writing, print, and digital media in addition to how they have been shaped by humans. She explores how each technological development alters what it is to be human, having an impact on our mental faculties, social connections, and cultural norms.

Technogenesis emphasizes that neither can be fully understood in isolation from the other and offers a framework to comprehend the complex interplay between people and technology. It provides a balanced viewpoint on technology that goes beyond deterministic or utopian viewpoints, considering both the advantages and disadvantages of new technical developments.

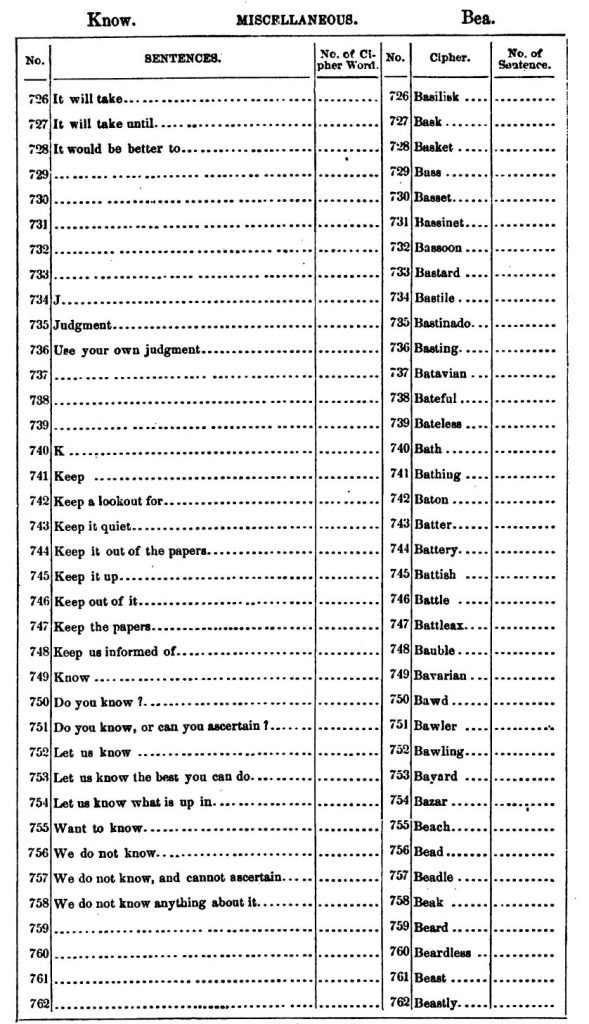

She applies this concept to the development and use of telegraph code books in the 19th and early 20th centuries. Telegraph code books were designed to simplify and economize telegraphic communication by substituting long phrases with shorter codes, thereby saving time and reducing costs. These books played a significant role in shaping not just the technology of telegraphy but also the humans who used them.

From a technogenic perspective, telegraph code books were not merely tools for efficient communication; they also influenced the way people thought about information, language, and even social relationships. The need for brevity and speed in telegraphy led to new forms of language and syntax, which in turn influenced journalistic styles, business practices, and even everyday communication. The code books standardized certain phrases and ways of conveying information, thus shaping the cognitive and communicative habits of those who used them.

Moreover, the use of code books had social and cultural implications. They were instrumental in the globalization of business and diplomacy, as they enabled faster and more efficient cross-border communication. This had a transformative effect on how business was conducted and how international relations were managed, thereby influencing societal structures.

In this way, the telegraph and its associated code books can be seen as part of a technogenic loop, where technology and human evolution influence each other in a continuous, dynamic relationship. The development of telegraph code books didn’t just stem from human ingenuity; it also shaped human practices, thought processes, and social structures, exemplifying the co-evolutionary relationship between humans and technology that is central to the concept of technogenesis.

For Hales, this is important to the larger history of how we understand the concept of “information.” She writes:

In the new regime the telegraph established, a zone of indeterminacy developed in which bodies seemed to take on some of the attributes of dematerialized information, and information seemed to take on the physicality of bodies. Nelson E. Ross, in “How to Write a Telegram Properly” (1927) recounts an anecdote in which a “countryman” wanted to send boots to his son: “He brought the boots to the telegraph office and asked that they be sent by wire. He had heard of money and flowers being sent by telegraph, so why not boots? [The operator] told the father to tie the boots together and toss them over the telegraph wire… [The countryman] remained until nightfall, watching to see the boots start on their long journey… [but] during the night, some one stole the boots. When the old man returned in the morning, he said: ‘Well, I guess the boy has the boots by now’” (12). The old man’s mistake was merely in thinking he could supply the boots, for in the same booklet, Ross writes about the “telegraphic shopping service,” which “permits the purchase by telegraph of any standardized article from a locomotive to a paper or pins. The person wishing to make the purchase has merely to call at the telegraph office, specify the article he wishes to have bought, and pay the cost, plus a small charge for the service. Directions will be telegraphed to the point at which the purchase is to be made, and an employee will buy the article desired” (13). The purchase is then either delivered in the same manner as a telegram or, if the recipient lives elsewhere, forwarded by parcel post. Thus bodies and information interpenetrate, with information becoming a body upon completion of the transaction.”[10]

This blurring of the boundaries between material bodies and immaterial information plays a significant role in the development of a cultural understanding of the mind as dematerialized information, driving fantasies of being able to upload the human mind to a computer. This conceptualization of information played a major role in the development of cybernetic approaches to technology, which largely dominated the ideology behind technological development in the 20th century. Norman Wiener defines cybernetics as “control and communication in the animal and the machine.”[11]

Chronocentricity: The Internet Echoes the Telegraph

Tom Standage argues in his book, The Victorian Internet: The Remarkable Story of the Telegraph and the Nineteenth Century’s On-line Pioneers, that the telegraph was actually a much more disruptive invention in its time than the internet was.[12] He argues that chronocentricity, the belief that one’s own era is unprecedented and unique, often colors our perception of technological advancements. This notion is particularly evident when we consider the Internet, frequently hailed as a revolutionary leap in communication. When examined more closely, however, it becomes clear that many of the characteristics and effects of the Internet are not wholly novel but rather advancements of the telegraph. Although the Internet is frequently seen as the pinnacle of contemporary communication, it has a surprising amount of similarities to its precursor from the 19th century, both in terms of technological operation and sociological influence.

The once-groundbreaking telegraph has mostly been forgotten by society, yet its legacy lives on in modern communication tools like the telephone, fax machine, and most significantly, the Internet. The essential function of both the telegraph and the Internet is to make long-distance communication easier. As we’ve seen, both rely on a system of cables for their infrastructure and both facilitate communication across enormous distances.

This similarity extends to the very language of transmission. Computers exchange information through bytes, sequences of eight binary digits. This method of communication closely mirrors the eight-panel shutter telegraphs of yesteryears. While telegraph operators relied on codebooks and Morse code to translate these combinations into words, today’s computers use ASCII codes to represent characters. The fundamental principle of encoding and decoding information for transmission has remained consistent across both technologies.

A fascinating study of human behavior may be found in how society has responded to the telegraph and the Internet. The telegraph was initially received with a mix of amazement and cynicism. A lot of Victorians thought that the development of this new technology would end misunderstandings between nations and usher in a time of global peace. The founder of MIT’s Media Lab, Nicholas Negroponte, had a similar idea when he said that the Internet would blur international boundaries and foster a more peaceful global society. Both of these technologies were viewed as revolutionary forces that will change the way we think about nationalism and global citizenship.

However, these lofty ideals were not realized without challenges. Both the telegraph and the Internet became platforms for fraudulent activities almost as quickly as they were adopted for legitimate communication. During the telegraph era, scam artists manipulated stock prices and horse racing results, exploiting the technology for personal gain. Today, the Internet is a hotbed for scams, from phishing emails to fraudulent websites. Security concerns have been a constant companion to both technologies. In the 19th century, secret codes were used to secure telegraphic messages, much like the encryption software that protects our online data today.

These technologies’ cultural modifications have also been quite comparable. Terms like “netizens” and “surfers” have entered the vernacular, just as the telegraph did with its own unique set of jargon. Both networks have also experienced some tribalism among users, with devoted users frequently clashing with newcomers. Even the online wedding phenomenon has its roots in the telegraph age.

Moreover, both technologies have been blamed for increasing the pace and stress of life, particularly in the business world. The telegraph led to more centralized business operations, as rapid communication allowed for tighter control from headquarters. The Internet, while enabling remote work, has also led to the centralization of data and the constant demand for immediate responses, contributing to what many describe as “information overload.”

The hype, skepticism, and general bewilderment that often accompany discussions about the Internet find their historical counterparts in the public reaction to the telegraph. These similarities suggest that while the technologies themselves evolve, the human elements—our ways of interacting with these platforms and the societal impacts they engender—remain remarkably consistent. Therefore, it may be worthwhile to keep in mind that many of the difficulties and opportunities we identify with the Internet were also discussed in relation to the telegraph the next time we are tempted to conceive of our period as being unusually revolutionary. The telegraph was, in many respects, as startling and transformative for its era as the Internet is for ours, serving as a reminder that every generation must deal with its own revolutionary developments, even if they are not as novel as we may like to believe. Standage concludes:

Time traveling Victorians arriving in the late twentieth century would, no doubt, be unimpressed by the Internet. They would surely find space flight and routine intercontinental air travel far more impressive technological achievements than our much-trumpeted global communications network. Heavier-than-air flying machines were, after all, thought by the Victorians to be impossible. But as for the Internet – well, they had one of their own.[13]

Standage’s comparison of the telegraph and the Internet should remind us to think carefully about how all of our views of contemporary communication could be shaped by our chronocentricity. Most of our new technology really isn’t that new, afterall. An important skill in the world of media studies is being able to see how previous technologies have influenced not only contemporary technologies, but also ourselves as human beings.

Key Takeaways

- Undersea cables, often overlooked in favor of satellites, serve as the backbone of global communications and are shaped by a complex mix of technological, human, and geopolitical factors.

- The concept of “technogenesis” challenges the conventional view of technology as merely a tool, highlighting the co-evolutionary relationship between humans and technology in shaping cognition, social institutions, and even biology.

- The idea of “chronocentricity” warns against the belief that our era’s technological advancements are unprecedented, encouraging a more nuanced understanding of how new technologies are often evolutions of previous ones, like the Internet’s roots in telegraph technology.

Exercises

- How do undersea cables exemplify the interconnectedness of technology, geopolitics, and human factors? Discuss the role of cable stations as geopolitical hotspots and their impact on global communications.

- Research the history and development of a specific undersea cable system, including viewing it on Surfacing website . Present your findings, focusing on how technological, human, and geopolitical factors have influenced its establishment and operation. Include screenshots from the mapping tool.

- In what ways does the concept of “technogenesis” challenge or support your own views on the relationship between humans and technology? Provide examples to illustrate your perspective.

Media Attributions

- Cross section of a telegraph cable © Image by J.J. Sylvia IV is licensed under a CC BY-NC-SA (Attribution NonCommercial ShareAlike) license

- Cross section of a telegraph cable 2 © Image by J.J. Sylvia IV is licensed under a CC BY-NC-SA (Attribution NonCommercial ShareAlike) license

- French Cable Station Museum © Image by J.J. Sylvia IV is licensed under a CC BY-NC-SA (Attribution NonCommercial ShareAlike) license

- French Cable Station Museum plague © Image by J.J. Sylvia IV is licensed under a CC BY-NC-SA (Attribution NonCommercial ShareAlike) license

- Eastern Telegraph cables © Wikipedia is licensed under a Public Domain license

- World Time Zones Map © Wikipedia is licensed under a Public Domain license

- Telegraphy code book page © Bloomer's is licensed under a Public Domain license

- Starosielski, Nicole. The Undersea Network. Sign, Storage, Transmission. Durham: Duke University Press, 2015. ↵

- https://www.frenchcablestationmuseum.org/museum-history.htm ↵

- Carey, James. “Technology and Ideology: The Case of the Telegraph.” In Communication as Culture: Essays on Media and Society, 201–30. Boston: Unwin Hyman, 1988. ↵

- Headrick, Daniel R. The Tools of Empire: Technology and European Imperialism in the Nineteenth Century. New York: Oxford University Press, 1981. ↵

- Standage, Tom. The Victorian Internet: The Remarkable Story of the Telegraph and the Nineteenth Century’s on-Line Pioneers. New York London Oxford New Delhi Sydney: Bloomsbury, 2014. ↵

- Bayly, Christopher Alan. Empire and Information: Intelligence Gathering and Social Communication in India, 1780 - 1870. 1. paperback ed. Cambridge Studies in Indian History and Society 1. Cambridge: Cambridge Univ. Press, 2006. ↵

- Hayes, Derek. Canada: An Illustrated History. Vancouver / Toronto: Douglas & McIntyre, 2004, p. 157 ↵

- ibid ↵

- Hayles, N. Katherine. How We Think: Digital Media and Contemporary Technogenesis. Chicago ; London: The University of Chicago Press, 2012. ↵

- ibid, p. 148 ↵

- Wiener, Norbert. Cybernetics or Control and Communication in the Animal and the Machine. 2. ed., 14. print. Cambridge, Mass: MIT Press, 2007. ↵

- Standage, Tom. The Victorian Internet: The Remarkable Story of the Telegraph and the Nineteenth Century’s on-Line Pioneers. New York London Oxford New Delhi Sydney: Bloomsbury, 2014. ↵

- ibid. p. 213 ↵