14.1 The Evolution of Electronic Games

Learning Objectives

- Identify the major companies involved in video game production.

- Explain the important innovations that drove the acceptance of video games by mainstream culture.

- Determine major technological developments that influenced the evolution of video games.

Pong, the electronic table tennis simulation game, was the first video game for many people who grew up in the 1970s and is now a famous symbol of early video games. However, the precursors to modern video games were created as early as the 1950s. In 1952 a computer simulation of tic-tac-toe was developed for the Electronic Delay Storage Automatic Calculator (EDSAC), one of the first stored-information computers, and in 1958 a game called Tennis for Two was developed at Brookhaven National Laboratory as a way to entertain people coming through the laboratory on tours.[1]

These games would generate little interest among the modern game-playing public, but at the time, they enthralled their users and introduced the basic elements of the cultural video game experience. In a time before personal computers, these games allowed the general public to access technology that had been restricted to the realm of abstract science. Tennis for Two created an interface where anyone with basic motor skills could use a complex machine. The first video games functioned early on as a form of media by essentially disseminating the experience of computer technology to those who did not have access to it.

As video games evolved, their role as a form of media grew as well. Video games have grown from simple tools that made computing technology understandable to forms of media that can communicate cultural values and human relationships.

The 1970s: The Rise of the Video Game

The 1970s saw the rise of video games as a cultural phenomenon. A 1972 article in Rolling Stone describes the early days of computer gaming:

Reliably, at any nighttime moment (i.e. non-business hours) in North America hundreds of computer technicians are effectively out of their bodies, locked in life-or-death space combat computer-projected onto cathode ray tube display screens, for hours at a time, ruining their eyes, numbing their fingers in frenzied mashing of control buttons, joyously slaying their friend and wasting their employers’ valuable computer time. Something basic is going on.[2]

This scene was describing Spacewar!, a game developed in the 1960s at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology (MIT) that spread to other college campuses and computing centers. In the early ’70s, very few people owned computers. Most computer users worked or studied at university, business, or government facilities. Those with access to computers were quick to utilize them for gaming purposes.

Arcade Games

The first coin-operated arcade game was modeled on Spacewar! It was called Computer Space, and it fared poorly among the general public because of its difficult controls. In 1972, Pong, the table-tennis simulator that has come to symbolize early computer games, was created by the fledgling company Atari, and it was immediately successful. Pong was initially placed in bars with pinball machines and other games of chance, but as video games grew in popularity, they were placed in any establishment that would take them. By the end of the 1970s, so many video arcades were being built that some towns passed zoning laws limiting them.[3]

The end of the 1970s ushered in a new era—what some call the golden age of arcade games—with the game Space Invaders, an international phenomenon that exceeded all expectations. In Japan, the game was so popular that it caused a national coin shortage. Games like Space Invaders illustrate both the effect of arcade games and their influence on international culture. In two different countries on opposite sides of the globe, Japanese and American teenagers, although they could not speak to one another, were having the same experiences thanks to a video game.

The Hangers

Fitchburg State University professor, Samuel Tobin, delves into the complex social dynamics of 1980s video arcades, expanding the narrative beyond the conventional focus on active gamers to include the often-overlooked “hangers”—individuals who frequented these spaces without necessarily engaging in gameplay. Tobin explores how different payment models, such as pay-per-game and flat-fee systems, influenced not only the types of players who visited arcades but also the social interactions that occurred within these spaces. He scrutinizes the role of arcade attendants, who were tasked with maintaining order and control, emphasizing that their responsibilities extended to monitoring both players and hangers.[4]

Tobin argues that these hangers were a vital yet underappreciated component of the arcade ecosystem. Utilizing a variety of tactics to remain in the arcade without drawing the attention of attendants, hangers subtly resisted the rules and norms established by arcade operators. Tobin contends that the decline of arcades in the late ’90s was not solely due to the advent of advanced home gaming systems but was also influenced by the migration of social interactions to online platforms. By examining the nuanced behaviors and strategies of hangers, Tobin’s work challenges us to reconsider who constitutes a participant in gaming spaces and invites us to explore the multifaceted ways in which individuals interact within these environments.[5]

Video Game Consoles

The first video game console for the home began selling in 1972. It was the Magnavox Odyssey, and it was based on prototypes built by Ralph Baer in the late 1960s. This system included a Pong-type game, and when the arcade version of Pong became popular, the Odyssey began to sell well. Atari, which was making arcade games at the time, decided to produce a home version of Pong and released it in 1974. Although this system could only play one game, its graphics and controls were superior to the Odyssey, and it was sold through a major department store, Sears. Because of these advantages, the Atari home version of Pong sold well, and a host of other companies began producing and selling their own versions of Pong.[6]

A major step forward in the evolution of video games was the development of game cartridges that stored the games and could be interchanged in the console. With this technology, users were no longer limited to a set number of games, leading many video game console makers to switch their emphasis to producing games. Several groups, such as Magnavox, Coleco, and Fairchild, released versions of cartridge-type consoles, but Atari’s 2600 console had the upper hand because of the company’s work on arcade games. Atari capitalized off of its arcade successes by releasing games that were well known to a public that was frequenting arcades. The popularity of games such as Space Invaders and Pac-Man made the Atari 2600 a successful system. The late 1970s also saw the birth of companies such as Activision, which developed third-party games for the Atari 2600.[7]

Ralph Baer’s Contributions

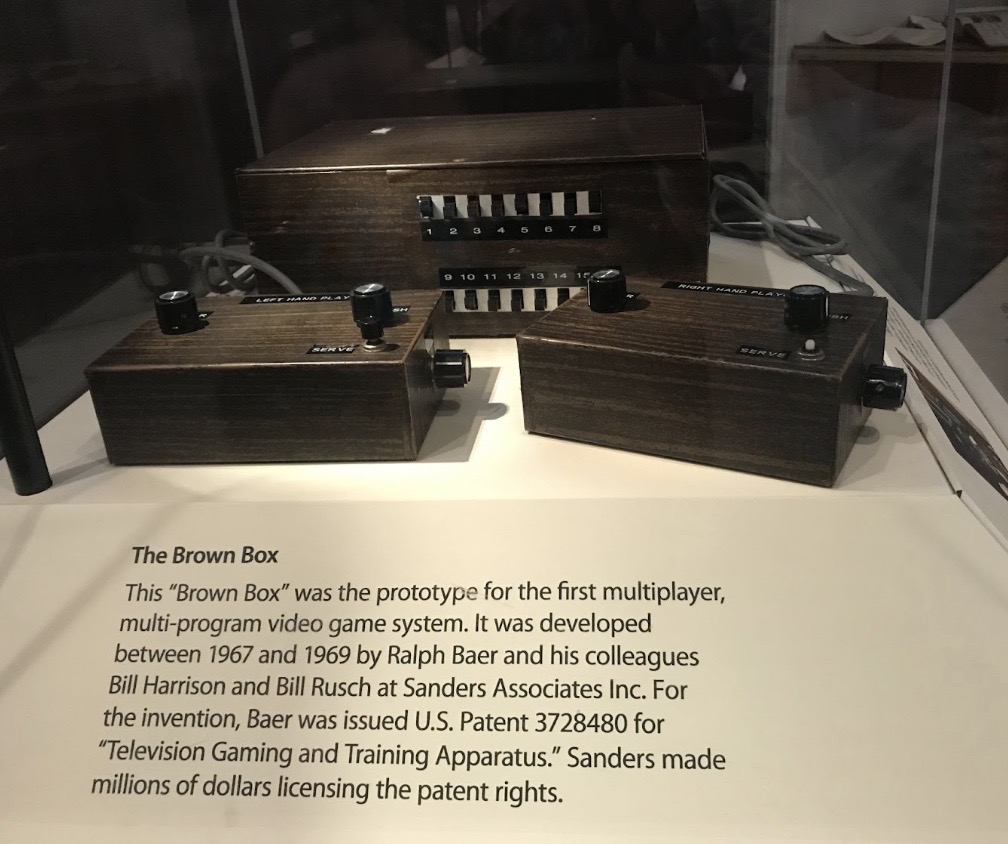

Ralph Baer, often hailed as the “Father of Videogames,” made groundbreaking contributions to the world of gaming while working at Sanders Associates in Nashua, New Hampshire. His seminal invention, initially known as the “Brown Box,” laid the foundation for the first-ever video game console, the Magnavox Odyssey. Developed between the mid to late 1960s, the console featured a variety of games, including the ping pong game that became a sensation. Baer’s vision was not just about technology; he aimed to create a form of family entertainment, assuming from the outset that the games would be played by multiple people.

Beyond the Magnavox Odyssey, Baer had a hand in various other gaming projects and electronic toys throughout the 1970s. He was instrumental in the development of arcade games like Hit-N-Run, Pro Soccer, and Skate-N-Score, as well as home consoles like Coleco Telstar. His influence even extended to electronic handheld games like Simon. Baer’s work has deep roots in New Hampshire, making it a significant location in the history of video game development. His legacy is commemorated by the American Classic Arcade Museum (ACAM), which proudly displays a replica of the “Brown Box,” serving as a testament to Baer’s enduring impact on the gaming industry.

Home Computers

The birth of the home computer market in the 1970s paralleled the emergence of video game consoles. The first computer designed and sold for the home consumer was the Altair. It was first sold in 1975, several years after video game consoles had been selling, and it sold mainly to a hobbyist market. During this period, people such as Steve Jobs, the founder of Apple, were building computers by hand and selling them to get their start-up businesses going. In 1977, three important computers—Radio Shack’s TRS-80, the Commodore PET, and the Apple II—were produced and began selling to the home market.[8]

The rise of personal computers allowed for the development of more complex games. Designers of games such as Mystery House, developed in 1979 for the Apple II, and Rogue, developed in 1980 and played on IBM PCs, used the processing power of early home computers to develop video games that had extended plots and storylines. In these games, players moved through landscapes composed of basic graphics, solving problems and working through an involved narrative. The development of video games for the personal computer platform expanded the ability of video games to act as media by allowing complex stories to be told and new forms of interaction to take place between players.

The 1980s: The Crash

Atari’s success in the home console market was due in large part to its ownership of already-popular arcade games and the large number of game cartridges available for the system. These strengths, however, eventually proved detrimental to the company and led to what is now known as the video game crash of 1983. Atari bet heavily on its past successes with popular arcade games by releasing Pac-Man for the Atari 2600. Pac-Man was a successful arcade game that did not translate well to the home console, leading to disappointed consumers and lower-than-expected sales. Additionally, Atari produced 10 million of the lackluster Pac-Man games on its first run, despite the fact that active consoles were only estimated at 10 million. Similar mistakes were made with a game based on the movie E.T.: The Extra-Terrestrial, which has gained notoriety as one of the worst games in Atari’s history. It was not received well by consumers despite the success of the movie, and Atari had again bet heavily on its success. Piles of unsold E.T. game cartridges were reportedly buried in the New Mexico desert under a veil of secrecy.[9]

As retail outlets became increasingly wary of home console failures, they began stocking fewer games on shelves. This action, combined with an increasing number of companies producing games, led to overproduction and a resulting fallout in the video game market in 1983. Not only that, there were multiple consoles with their own libraries. Multiple companies were battling for a small market. Another big issue is the fact that video games were seen as kids’ toys and not an overall medium for all ages. In other words, those who were buying video games weren’t the fans playing them, but rather the parents.

Many smaller game developers did not have the capacity to withstand this downturn and went out of business. Although Coleco and Atari were able to make it through the crash, neither company regained its former share of the video game market. It was 1985 when the video game market picked up again.

The Rise of Nintendo

Nintendo, a Japanese card and novelty producer that had begun to produce electronic games in the 1970s, was responsible for arcade games such as Donkey Kong in the early 1980s. Its first home console, developed in 1984 for sale in Japan, tried to succeed where Atari had failed. The Nintendo system (known as Famicom in Japan) used newer, better microchips, bought in large quantities, to ensure high-quality graphics at a price consumers could afford. Keeping console prices low meant Nintendo had to rely on games for most of its profits and maintain control of game production. This was something Atari had failed to do, and it led to a glut of low-priced games that caused the crash of 1983. Nintendo got around this problem with proprietary circuits that would not allow unlicensed games to be played on the console. This would become the standard for many game consoles to come, with most games for the console being on proprietary hardware. The cartridge system still exists as of 2023 in the form of the Nintendo Switch. This degree of quality control and the increased scope of video games that go beyond simple arcade experiences caused Nintendo to become a household name. This allowed one-third of homes in the United States to have a Nintendo system.[10]

Nintendo introduced its Nintendo Entertainment System (NES) in the United States in 1985. The game Super Mario Brothers, released with the system, was also a landmark in video game development. The game employed a narrative in the same manner as more complicated computer games, but its controls were accessible and its objectives were simple. The game appealed to a younger demographic, generally boys in the 8–14 range, than the one targeted by Atari.[11] Its designer, Shigeru Miyamoto, tried to mimic the experiences of childhood adventures, creating a fantasy world not based on previous models of science fiction or other literary genres.[12] Super Mario Brothers also gave Nintendo an iconic character who has been used in numerous other games, television shows, and even a movie. The development of this type of character and fantasy world became the norm for video game makers. Games such as The Legend of Zelda became franchises with film and television possibilities rather than simply one-off games.

As video games developed as a form of media, the public struggled to come to grips with the kind of messages this medium was passing on to children. These were no longer simple games of reflex that could be compared to similar non-video games or sports; these were forms of media that included stories and messages that concerned parents and children’s advocates. Arguments about the larger meaning of the games became common, with some seeing the games as driven by ideas of conquest and gender stereotypes, whereas others saw basic stories about traveling and exploration.[13]

Over a 20 year period, Nintendo went from a great to not-so-great company. Starting in the mid 1980’s “Golden Age”, the NES was the next big thing. Following this, in the early to mid 90’s, we saw their “Silver Age” with the Super NES, doubling the data these consoles stored from its predecessor. Finally in the mid 90’s to mid 2000’s, Nintendo fell into its worst times, or “Dark Age”. The newest system at this time quadrupled the data of the previous system, but this wasn’t enough to keep them at the top. It’s very important when viewing a product to look at what came before this, and how previous designs influenced what you are looking at. This will be talked about extensively in this chapter.

While studying the history of Nintendo, it’s important to ask ourselves a few questions. What makes Nintendo important? Why do people use Nintendo products over others? Is Nintendo just video games? To start on that last question, no, Nintendo is not just video games. Originally, Nintendo was producing playing cards which then advanced to video games as technology improved. This is important because we can see Nintendo has a history of developing games with modern technology.

Nintendo over the years has developed a range of different products, not all just being home consoles. Two of these products are specific and the 3DS and Wii Balance Boards. These two items were used in research to help people in need. For the 3DS, non-English speaking patients of all ages were able to perform different forms of near-vision tests more than a quarter of the time more quickly than their original methods. The game they used was called “PDI Check” on the 3DS, which is a vision screening game displaying stereoscopic images without the need of special equipment like glasses, headsets or anything else. It was now condensed into the Nintendo 3DS. But this was just a coincidence. Why should Nintendo get credit for research that just happened to use their product? The Nintendo 3DS wasn’t intended to be used for research purposes.

Many companies release products with an intended purpose. For example, most Nintendo items are for pass time. They are known for putting out video games. So is it a bad thing when someone uses their item for a purpose other than what it was created for? An interview at Fitchburg State University with Dr. Sam Tobin, a game design professor and author of Portable Play in Everyday Life: The Nintendo DS. talks about questions like these and much more.

Tobin is asked about his thoughts on product usage by consumers. There is no way to control how someone uses a product you make for them once they purchase it. He goes in depth with great examples such as “The car wasn’t made to crash” and points out how everything will have good and bad, or an accident. He explains how all technology has these accidents that can be results of trying to do good in the world. “There are consequences with the usage of technology that are unavoidable.”

Tobin is then questioned on the idea of restricting permissions of usage to avoid the previous problem. His first thought is that this could never happen after quickly pointing out that it’s already the world we live in today. “Do you really own the objects you own?” are the words Tobin uses to show that just because we purchase something and can say it’s ours, we do not have full control over it. This is something very important to point out because it definitely goes over all our heads.

Other Home Console Systems

Other software companies were still interested in the home console market in the mid-1980s. Atari released the 2600jr and the 7800 in 1986 after Nintendo’s success, but the consoles could not compete with Nintendo. The Sega Corporation, which had been involved with arcade video game production, released its Sega Master System in 1986. Although the system had more graphics possibilities than the NES, Sega failed to make a dent in Nintendo’s market share until the early 1990s, with the release of Sega Genesis.[14]

Computer Games Flourish and Innovate

The enormous number of games available for Atari consoles in the early 1980s took its toll on video arcades. In 1983, arcade revenues had fallen to a 3-year low, leading game makers to turn to newer technologies that could not be replicated by home consoles. This included arcade games powered by laser discs, such as Dragon’s Lair and Space Ace, but their novelty soon wore off, and laser-disc games became museum pieces.[15] In 1989, museums were already putting on exhibitions of early arcade games that included ones from the early 1980s. Although newer games continued to come out on arcade platforms, they could not compete with the home console market and never achieved their previous successes from the early 1980s. Increasingly, arcade gamers chose to stay at home to play games on computers and consoles. Today, dedicated arcades are a dying breed. Most that remain, like the Dave & Buster’s and Chuck E. Cheese’s chains, offer full-service restaurants and other entertainment attractions to draw in business.

Home games fared better than arcades because they could ride the wave of personal computer purchases that occurred in the 1980s. Some important developments in video games occurred in the mid-1980s with the development of online games. Multi-user dungeons, or MUDs, were role-playing games played online by multiple users at once. The games were generally text-based, describing the world of the MUD through text rather than illustrating it through graphics. The games allowed users to create a character and move through different worlds, accomplishing goals that awarded them with new skills. If characters attained a certain level of proficiency, they could then design their own area of the world. Habitat, a game developed in 1986 for the Commodore 64, was a graphic version of this type of game. Users dialed up on modems to a central host server and then controlled characters on screen, interacting with other users.[16]

One of the more important computers to come out in the 80s was Japan’s NEC PC-8800 series. A lot of popular companies that exist today actually found their footing in the PC market. Not having to worry about getting denied by Nintendo or Sega because of what they wanted your game to be, you could just release it on PC without paying cartridge fees. For example, Square, which would go on to become Square Enix, started making games on the PC-8800.

During the mid-1980s, a demographic shift occurred. Between 1985 and 1987, games designed to run on business computers rose from 15 percent to 40 percent of games sold.[17] This trend meant that game makers could use the increased processing power of business computers to create more complex games. It also meant adults were interested in computer games and could become a profitable market.

The 1990s: The Rapid Evolution of Video Games

Video games evolved at a rapid rate throughout the 1990s, moving from the first 16-bit systems (named for the amount of data they could process and store) in the early 1990s to the first Internet-enabled home console in 1999. As companies focused on new marketing strategies, wider audiences were targeted, and video games’ influence on culture began to be felt.

Console Wars

Nintendo’s dominance of the home console market throughout the late 1980s allowed it to build a large library of games for use on the NES. This also proved to be a weakness, however, because Nintendo was reluctant to improve or change its system for fear of making its game library obsolete. Technology had changed in the years since the introduction of the NES, and companies such as NEC and Sega were ready to challenge Nintendo with 16-bit systems.[18]

The Sega Master System had failed to challenge the NES, but with the release of its 16-bit system, the Sega Genesis, the company pursued a new marketing strategy. Whereas Nintendo targeted 8- to 14-year-olds, Sega’s marketing plan targeted 15- to 17-year-olds, making games that were more mature and advertising during programs such as the MTV Video Music Awards. The campaign successfully branded Sega as a cooler version of Nintendo and moved mainstream video games into a more mature arena. Nintendo responded to the Sega Genesis with its own 16-bit system, the Super NES, and began creating more mature games on consoles as well. Games such as Sega’s Mortal Kombat and Nintendo’s Street Fighter competed to raise the level of violence possible in a video game. Sega’s advertisements even suggested that its game was better because of its more violent possibilities.[19] Games such as Final Fantasy 6 went for more mature storylines, showing themes that weren’t able to be tackled before on home console games.

By 1994, companies such as 3DO, with its 32-bit system, and Atari, with its allegedly 64-bit Jaguar, attempted to get in on the home console market but failed to use effective marketing strategies to back up their products. Both systems fell out of production before the end of the decade. Sega, fearing that its system would become obsolete, released the 32-bit Saturn system in 1995. The system was rushed into production and did not have enough games available to ensure its success.[20] Sony stepped in with its PlayStation console at a time when Sega’s Saturn was floundering and before Nintendo’s 64-bit system had been released. This system targeted an even older demographic. With its E3 reveal in 1995, at a time when most consoles focused almost exclusively on younger audiences, Sony pitched their console to the general public. The console had a large effect on the market; by March of 2007, Sony had sold 102 million PlayStations.[21]

Computer Games Gain Mainstream Acceptance

Computer games had avid players, but they were still a niche market in the early 1990s. An important step in the mainstream acceptance of personal computer games was the development of the first-person shooter genre. First popularized by the 1992 game Wolfenstein 3D, these games put the player in the character’s perspective, making it seem as if the player were firing weapons and being attacked. Doom, released in 1993, and Quake, released in 1996, used the increased processing power of personal computers to create vivid three-dimensional worlds that were impossible to fully replicate on video game consoles of the era. These games pushed realism to new heights and began attracting public attention for their graphic violence.

Another trend was reaching out to audiences outside of the video-game-playing community. Myst, an adventure game where the player walked around an island solving a mystery, drove sales of CD-ROM drives for computers. Myst, its sequel Riven, and other non-violent games such as SimCity actually outsold Doom and Quake in the 1990s.[22] These nonviolent games appealed to people who did not generally play video games, increasing the form’s audience and expanding the types of information that video games put across.

Online Gaming Gains Popularity

A major advance in game technology came with the increase in Internet use by the general public in the 1990s. A major feature of Doom was the ability to use multiplayer gaming through the Internet. Strategy games such as Command and Conquer and Total Annihilation also included options where players could play each other over the Internet. Other fantasy-inspired role-playing games, such as Ultima Online, used the Internet to initiate the massively multiplayer online role-playing game (MMORPG) genre.[23] These games used the Internet as their platform, much like the text-based MUDs, creating a space where individuals could play the game while socially interacting with one another.

Portable Game Systems

The development of portable game systems was another important aspect of video games during the 1990s. Handheld games had been in use since the 1970s, and a system with interchangeable cartridges had even been sold in the early 1980s. Nintendo released the Game Boy in 1989, using the same principles that made the NES dominate the handheld market throughout the 1990s. The Game Boy was released with the game Tetris, using the game’s popularity to drive purchases of the unit. The unit’s simple design meant users could get 20 hours of playing time on a set of batteries, and this basic design was left essentially unaltered for most of the decade. More advanced handheld systems, such as the Atari Lynx and Sega Game Gear, could not compete with the Game Boy despite their superior graphics and color displays.[24]

The decade-long success of the Game Boy belies the conventional wisdom of the console wars that more advanced technology makes for a more popular system. The Game Boy’s static, simple design was readily accessible, and its stability allowed for a large library of games to be developed for it. Despite using technology almost a decade old, the Game Boy accounted for 30 percent of Nintendo of America’s overall revenues at the end of the 1990s.[25]

The Early 2000s: 21st-Century Games

The Console Wars Continue

Sega gave its final effort in the console wars with the Sega Dreamcast in 1999. This console could connect to the Internet, emulating the sophisticated computer games of the 1990s. The new features of the Sega Dreamcast were not enough to save the brand, however, and Sega discontinued production in 2001, leaving the console market entirely.[26]

A major problem for Sega’s Dreamcast was Sony’s release of the PlayStation 2 (PS2) in 2000. The PS2 could function as a DVD player, expanding the role of the console into an entertainment device that did more than play video games. This console was incredibly successful, enjoying a long production run, with more than 106 million units sold worldwide by the end of the decade.[27]

In 2001, two major consoles were released to compete with the PS2: the Xbox and the Nintendo GameCube. The Xbox was an attempt by Microsoft to enter the market with a console that expanded on the functions of other game consoles. The unit had features similar to a PC, including a hard drive and an Ethernet port for online play through its service, Xbox Live. The popularity of the first-person shooter game Halo, an Xbox exclusive release, boosted sales as well. Nintendo’s GameCube did not offer DVD playback capabilities, choosing instead to focus on gaming functions. Both of these consoles sold millions of units but did not come close to the sales of the PS2.

The Evolution of Portable Gaming

Nintendo continued its control of the handheld game market into the 2000s with the 2001 release of the Game Boy Advance, a redesigned Game Boy that offered 32-bit processing and compatibility with older Game Boy games. In 2004, anticipating Sony’s upcoming handheld console, Nintendo released the Nintendo DS, a handheld console that featured two screens and Wi-Fi capabilities for online gaming. Sony’s PlayStation Portable (PSP) was released the following year and featured Wi-Fi capabilities as well as a flexible platform that could be used to play other media such as MP3s.[28] These two consoles, along with their newer versions, continue to dominate the handheld market.

One interesting innovation in mobile gaming occurred in 2003 with the release of the Nokia N-Gage. The N-Gage was a combination of a game console and mobile phone that, according to consumers, did not fill either role very well. The product line was discontinued in 2005, but the idea of playing games on phones persisted and has been developed on other platforms.[29] Apple currently dominates the industry of mobile phone games; in 2008 and 2009 alone, iPhone games generated $615 million in revenue.[30] As mobile phone gaming grows in popularity and as the supporting technology becomes increasingly more advanced, traditional portable gaming platforms like the DS and the PSP will need to evolve to compete. Nintendo is already planning a successor to the DS that features 3-D graphics without the use of 3-D glasses, which it hopes will help the company retain and grow its share of the portable gaming market.

Video Games Today

The trends of the late 2000s have shown a steadily increasing market for video games. Newer control systems and family-oriented games have made it common for many families to engage in video game play as a group. Online games have continued to develop, gaining unprecedented numbers of players. The overall effect of these innovations has been the increasing acceptance of video game culture by the mainstream.

Home Consoles in the 2000s

The current state of the home console market still involves the three major companies of the past 10 years: Nintendo, Sony, and Microsoft. The release of Microsoft’s Xbox 360 led this generation of consoles in 2005. The Xbox 360 featured expanded media capabilities and integrated access to Xbox Live, an online gaming service. Sony’s PlayStation 3 (PS3) was released in 2006. It also featured enhanced online access as well as expanded multimedia functions, with the additional capacity to play Blu-ray discs. Nintendo released the Wii at the same time. This console featured a motion-sensitive controller that departed from previous controllers and focused on accessible, often family-oriented games. This combination successfully brought in large numbers of new game players, including many older adults. In its lifetime, the Wii had over 101 million sales, while the PS3 had a late generation surge and managed to surpass the sales of the Xbox 360 with 87.4 million and 85.7 million units sold respectively.[31] In the wake of the Wii’s success, Microsoft and Sony have introduced their own motion-sensitive systems.[32]

The 2010s and beyond

The next generation of consoles would usher in a new dynamic in the ever-changing market as Nintendo introduced the long-anticipated successor to the Wii, the Wii U. The confusing name, along with poor marketing and lack of Nintendo’s more famous franchises being available on the console led to poor sales,[33] selling only 13.6 million units globally.

The PlayStation 4 continued Sony’s ascension to the top of the market as the Xbox One also suffered from poor marketing and a lack of focus on the console’s core features. The PS4 would break franchise records and sell 117 million units, while the Xbox One sold a respectable 57.9 million units.

In 2017, Nintendo launched the Nintendo Switch, their successor to the Wii U. While the console shared many features with its predecessor, the versatility it offered as a hybrid portable device and a strong library of games to choose from led to the Switch becoming Nintendo’s highest selling console of all time, selling a staggering 130.7 million units.[34]

Covid-19 and Online Gaming

In 2020, in the midst of the COVID-19 Pandemic, Sony and Microsoft launched the PlayStation 5 and Xbox Series X/S, respectively. This came at a time when video games were played by more people than ever since many looked to them as an escape from a scary time. According to a study by the University of Glasgow, the pandemic saw a 71% increase in playing time for people and a major shift toward online multiplayer games.[35]

One of the defining games of this era is Fortnite, which has set the industry standard for multiplayer shooters. Fortnite popularized the use of a controversial monetization system commonly referred to as the Battle Pass. The Battle Pass is commonly a seasonal payment that unlocks a timed unlock path, with these unlocks granting players cosmetic items as a reward for time spent playing the game. This recurring engagement loop leads to continuously high player counts, which leads to more opportunities for players to spend money.[36] This Battle Pass system is now in nearly every multiplayer shooter, from Battlefield to Call of Duty, to even games geared towards children like Fall Guys.

Key Takeaways

- In a time before personal computers, early video games allowed the general public to access technology that had been restricted to the realm of abstract science. Tennis for Two created an interface where anyone with basic motor skills could use a complex machine. The first video games functioned early on as a form of media by essentially disseminating the experience of computer technology to those without access to it.

- Video games reached wider audiences in the 1990s with the advent of the first-person shooter genre and popular nonaction games such as Myst. The games were marketed to older audiences, and their success increased demand for similar games.

- Online capabilities that developed in the 1990s and expanded in the 2000s allowed players to compete in teams. This innovation attracted larger audiences to gaming and led to new means of social communication.

- A new generation of accessible, family-oriented games in the late 2000s encouraged families to interact through video games. These games also brought in older demographics that had never used video games before.

Exercises

Video game marketing has changed to bring in more and more people to the video game audience. Think about the influence video games have had on you or people you know. If you have never played video games, then think about the ways your conceptions of video games have changed. Sketch out a timeline indicating the different occurrences that marked your experiences related to video games. Now compare this timeline to the history of video games from this section. Consider the following questions:

- How did your own experiences line up with the history of video games?

- Did you feel the effects of marketing campaigns directed at you or those around you?

- Were you introduced to video games during a surge in popularity? What games appealed to you?

Media Attributions

- Tennis For Two © Figure 1 A photo of Tennis for Two, a rudimentary game designed to entertain visitors to the Brookhaven National Laboratory. is licensed under a Public Domain license

- American Classic Arcade Museum entrance © Image by J.J. Sylvia IV is licensed under a CC BY-NC-SA (Attribution NonCommercial ShareAlike) license

- Coleco Vision video game system © mage by J.J. Sylvia IV is licensed under a CC BY-NC-SA (Attribution NonCommercial ShareAlike) license

- Replica of the “Brown Box” © Image by J.J. Sylvia IV is licensed under a CC BY-NC-SA (Attribution NonCommercial ShareAlike) license

- Ralph Baer’s home game design studio © Image by J.J. Sylvia IV is licensed under a CC BY-NC-SA (Attribution NonCommercial ShareAlike) license

- Egenfeldt-Nielsen, Simon. Understanding Video Games: The Essential Introduction (New York: Taylor & Francis, 2008), 50. ↵

- Brand, Stewart. “Space War,” Rolling Stone, December 7, 1972. ↵

- Kent, Steven. “Super Mario Nation,” American Heritage, September 1997, https://web.archive.org/web/20100116135603/http://americanheritage.com/articles/magazine/ah/1997/5/1997_5_65.shtml. ↵

- Tobin, Samuel. “Hanging in the Video Arcade.” Journal of Games Criticism (blog), July 2016. https://gamescriticism.org/2023/07/24/hanging-in-the-video-arcade/. ↵

- ibid ↵

- Herman, Leonard. “Early Home Video Game Systems,” in The Video Game Explosion: From Pong to PlayStation and Beyond, ed. Mark Wolf (Westport, CT: Greenwood Press, 2008), 54. ↵

- Wolf, Mark J. P. “Arcade Games of the 1970s,” in The Video Game Explosion (see note 7), 41. ↵

- Reimer, Jeremy. “The Evolution of Gaming: Computers, Consoles, and Arcade,” Ars Technica (blog), October 10, 2005, http://arstechnica.com/old/content/2005/10/gaming-evolution.ars/4. ↵

- Montfort, Nick and Ian Bogost, Racing the Beam: The Atari Video Computer System (Cambridge, MA: MIT Press, 2009), 127. ↵

- Cross, Gary and Gregory Smits, “Japan, the U.S. and the Globalization of Children’s Consumer Culture,” Journal of Social History 38, no. 4 (2005). ↵

- Kline, Stephen, Nick Dyer-Witheford, and Greig De Peuter, Digital Play: The Interaction of Technology, Culture, and Marketing (Montreal: McGill-Queen’s University Press, 2003), 119. ↵

- McLaughlin, Rus. “IGN Presents the History of Super Mario Bros.,” IGN Retro, November 8, 2007, https://web.archive.org/web/20100701134147/http://games.ign.com/articles/833/833615p1.html. ↵

- Fuller, Mary and Henry Jenkins, “Nintendo and New World Travel Writing: A Dialogue,” Cybersociety: Computer-Mediated Communication and Community, ed. Steven G. Jones (Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage Publications, 1995), 57–72. ↵

- Kerr, Aphra. “Spilling Hot Coffee? Grand Theft Auto as Contested Cultural Product,” in The Meaning and Culture of Grand Theft Auto: Critical Essays, ed. Nate Garrelts (Jefferson, NC: McFarland, 2005), 17. ↵

- Harmetz, Aljean. “Video Arcades Turn to Laser Technology as Queues Dwindle,” Morning Herald (Sydney), February 2, 1984. ↵

- Reimer, Jeremy. “Total share: 30 years of personal computer market share figures,” Ars Technica (blog), December 14, 2005, http://arstechnica.com/old/content/2005/12/total-share.ars/2. ↵

- Elmer-Dewitt, Philip and others, “Computers: Games that Grownups Play,” Time, July 27, 1987, https://web.archive.org/web/20130819192316/http://www.time.com/time/magazine/article/0,9171,965090,00.html. ↵

- Slaven, Andy. Video Game Bible, 1985–2002, (Victoria, BC: Trafford), 70–71. ↵

- Gamespot, “When Two Tribes Go to War: A History of Video Game Controversy,” http://www.gamespot.com/features/6090892/p-5.html. ↵

- CyberiaPC.com, “Sega Saturn (History, Specs, Pictures),” https://web.archive.org/web/20040116012755/http://www.cyberiapc.com/vgg/sega_saturn.htm. ↵

- Edge staff, “The Making Of: Playstation,” Edge, April 24, 2009, https://web.archive.org/web/20110507025227/http://www.next-gen.biz:80/features/the-making-of-playstation. ↵

- Miller, Stephen C. “News Watch; Most-Violent Video Games Are Not Biggest Sellers,” New York Times, July 29, 1999, http://www.nytimes.com/1999/07/29/technology/news-watch-most-violent-video-games-are-not-biggest-sellers.html. ↵

- Reimer, Jeremy. “Total share: 30 years of personal computer market share figures,” Ars Technica (blog), December 14, 2005, http://arstechnica.com/old/content/2005/12/total-share.ars/2. ↵

- Hutsko, Joe. “88 Million and Counting; Nintendo Remains King of the Handheld Game Players,” New York Times, March 25, 2000, http://www.nytimes.com/2000/03/25/business/88-million-and-counting-nintendo-remains-king-of-the-handheld-game-players.html. ↵

- ibid ↵

- Business Week, “Sega Dreamcast,” slide in “A Brief History of Game Console Warfare,” Business Week, https://archive.ph/Zfv8q. ↵

- A Brief History of Game Console Warfare, “PlayStation 2,” slide in “A Brief History of Game Console Warfare.” ↵

- Patsuris, Penelope. “Sony PSP vs. Nintendo DS,” Forbes, June 7, 2004, http://www.forbes.com/2004/06/07/cx_pp_0607mondaymatchup.html. ↵

- Stone, Brad. “Play It Again, Nokia. For the Third Time,” New York Times, August 27, 2007, http://www.nytimes.com/2007/08/27/technology/27nokia.html. ↵

- Farago, Peter. “Apple iPhone and iPod Touch Capture U.S. Video Game Market Share,” Flurry (blog), March 22, 2010, https://web.archive.org/web/20100326181135/http://blog.flurry.com/bid/31566/Apple-iPhone-and-iPod-touch-Capture-U-S-Video-Game-Market-Share. ↵

- VGChartz, “Weekly Hardware Chart: 19th June 2010,” http://www.vgchartz.com. ↵

- Mangalindan, J. P. “Is Casual Gaming Destroying the Traditional Gaming Market?” Fortune, March 18, 2010, https://web.archive.org/web/20130128232513/http://tech.fortune.cnn.com/2010/03/18/is-casual-gaming-destroying-the-traditional-gaming-market/. ↵

- Shay, R., & Palomba, A. (2020). First-Party Success or First-Party Failure? A Case Study on Audience Perceptions of the Nintendo Brand During the Wii U’s Product Life Cycle. Games and Culture, 15(5), 475–500. https://doi.org/10.1177/1555412018813666 ↵

- Platform Totals. (n.d.). VGChartz. Retrieved January 5, 2024, from https://www.vgchartz.com ↵

- Barr, M., & Copeland-Stewart, A. (2022). Playing Video Games During the COVID-19 Pandemic and Effects on Players’ Well-Being—Matthew Barr, Alicia Copeland-Stewart, 2022. Games and Culture, 17(1), 122–139. https://doi.org/10.1177/15554120211017036 ↵

- Joseph, Daniel. (2021) “Battle Pass Capitalism.” Journal of Consumer Culture 21(1), 68–83. https://doi.org/10.1177/1469540521993930 ↵