17.1 Ethical Issues in Mass Media

Learning Objectives

- Explain the importance of racial and gender diversity in mass media.

- Identify the ethical concerns associated with race and gender stereotypes.

- List some common concerns about sexual content in the media.

In the competitive and rapidly changing world of mass-media communications, media professionals—overcome by deadlines, bottom-line imperatives, and corporate interests—can easily lose sight of the ethical implications of their work. However, as entertainment law specialist Sherri Burr points out, “Because network television is an audiovisual medium that is piped free into ninety-nine percent of American homes, it is one of the most important vehicles for depicting cultural images to our population.”[1] Considering the profound influence mass media like television have on cultural perceptions and attitudes, it is important for the creators of media content to grapple with ethical issues.

Stereotypes, Prescribed Roles, and Public Perception

The U.S. population is becoming increasingly diverse. According to U.S. Census statistics from 2010, 27.6 percent of the population identifies its race as non-White.[2] Yet in network television broadcasts, major publications, and other forms of mass media and entertainment, minorities are often either absent or presented as heavily stereotyped, two-dimensional characters. Rarely are minorities depicted as complex characters with the full range of human emotions, motivations, and behaviors. Meanwhile, the stereotyping of women, gays and lesbians, and individuals with disabilities in mass media has also been a source of concern. Straightwashing, when minor groups are portrayed by a cis or heterosexual actor in media, has been an issue constantly tackled again and again. Although awareness of the issue is being brought upon, cis actors can still be seen being offered trans roles, and the same with heterosexual actors and homosexual roles.[3]

The word stereotype originated in the printing industry as a method of making identical copies, and the practice of stereotyping people is much the same: a system of identically replicating an image of an “other.” The origins and current meaning of stereotypes is also reflected off of the general expectations about particular social group members.[4] As we saw previously, D. W. Griffith’s The Birth of a Nation, a film that relied on racial stereotypes to portray Southern Whites as victims in the American Civil War, stereotypes—especially those disseminated through mass media—become a form of social control, shaping collective perceptions and individual identities. Stereotyping is often used to make sense of the world. For example, stereotypical expectations activate specific areas in the brain that help one identify, interpret, and remember what we see, hear, and learn about others.[5] In American mass media, the White man is still shown as the standard: the central figure of TV narratives and the dominant perspective on everything from trends, to current events, to politics. White maleness becomes an invisible category because it gives the impression of being the norm.[6]

Minority Exclusion and Stereotypes

In the fall of 1999, when the major television networks released their schedules for the upcoming programming season, a startling trend became clear. Of the 26 newly released TV programs, none depicted an African American in a leading role, and even the secondary roles on these shows included almost no racial minorities. When minorities do appear on screen, they are narrowed down to stereotypical and derogatory depictions whether they are black or gay.[7] In response to this omission, the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People (NAACP) and the National Council of La Raza (NCLR), an advocacy group for Hispanic Americans, organized protests and boycotts. Pressured—and embarrassed—into action, the executives from the major networks made a fast dash to add racial minorities to their prime-time shows, not only among actors but also among producers, writers, and directors. Four of the networks—ABC, CBS, NBC, and Fox—added a vice president of diversity position to help oversee the networks’ progress toward creating more diverse programming.[8]

Despite these changes and greater public attention regarding diversity issues, minority underrepresentation is still an issue in all areas of mass media. In fact, the trend in recent years has been regressive. In a recent study, the NAACP reported that the number of minority actors on network television has actually decreased, from 333 during the 2002–2003 season to 307 four years later.[9] There is also the case of whitewashing, in which a character of color in the media is portrayed by a white actor. Some modern examples include Johnny Depp as a Native American in Lone Ranger (2013) and Scarlett Johansson as a Japanese woman in Ghost In the Shell (2017).[10] Racial minorities are often absent, peripheral, or take on stereotyped roles in film, television, print media, advertising, and even in video games. Additionally, according to a 2002 study by the University of California, Los Angeles, the problem is not only a visible one, but also one that extends behind the scenes. The study found that minorities are even more underrepresented in creative and decision-making positions than they are on screen.[11] This lack of representation among producers, writers, and directors often directly affects the way minorities are portrayed in film and television, leading to racial stereotypes. There is also the case of colorblindness. What originally started as a way to give minorities the same opportunities as white actors by “not seeing race,” colorblindness, unfortunately, failed to acknowledge social borders and denied the existence of racism.[12]

Though advocacy groups like the NCLR and the NAACP have often been at the forefront of protests against minority stereotypes in the media, experts are quick to point out that the issue is one everyone should be concerned about. As media ethicist Leonard M. Baynes argues, “Since we live in a relatively segregated country…broadcast television and its images and representations are very important because television can be the common meeting ground for all Americans.”[13] There are clear correlations between mass media portrayals of minority groups and public perceptions. In 1999, after hundreds of complaints by African Americans that they were unable to get taxis to pick them up, the city of New York launched a crackdown, threatening to revoke the licenses of cab drivers who refused to stop for African American customers. When interviewed by reporters, many cab drivers blamed their actions on fears they would be robbed or asked to drive to dangerous neighborhoods.[14]

Racial stereotypes are not only an issue in entertainment media; they also find their way into news reporting, which is a form of storytelling. This topic goes into the discussion of ethnic or transnational literature presenting a challenge to historical ways of thinking as well as organizing the study of the terms of nations, religions, etc. These challenges are unfortunately overlooked and dismissed in favor of preferring privileged literacy over historical constructions of identity.[15] Journalists, editors, and reporters are still predominately white. According to a 2000 survey, only 11.6 percent of newsroom staff in the United States were racial and ethnic minorities.[16] The situation has not improved dramatically during the past decade. According to a 2008 newsroom census released by the American Society of Newspaper Editors, the percentage of minority journalists working at daily newspapers was a scant 13.52 percent.[17] Because of this underrepresentation behind the scenes, the news media is led by those whose perspective is already privileged, who create the narratives about those without privilege. In the news media, racial minorities are often cast in the role of villains or troublemakers, which in turn shapes public perceptions about these groups. Media critics Robert Entman and Andrew Rojecki point out that images of African Americans on welfare, African American violence, and urban crime in African American communities “facilitate the construction of menacing imagery.”[18] Similarly, a study by the National Association of Hispanic Journalists found that only 1 percent of the evening news stories aired by the three major U.S. television networks cover Latinos or Latino issues and that when Latinos are featured, they are portrayed negatively 80 percent of the time.[19] Still others have criticized journalists and reporters for a tendency toward reductive presentations of complex issues involving minorities, such as the religious and racial tensions fueled by the September 11 attacks. By reducing these conflicts to “opposing frames”—that is, by oversimplifying them as two-sided struggles so that they can be quickly and easily understood—the news media helped create a greater sense of separation between Islamic Americans and the dominant culture after September 11, 2001.[20]

Since the late 1970s, the major professional journalism organizations in the United States—Associated Press Managing Editors (APME), Newspaper Association of America (NAA), American Society of Newspaper Editors (ASNE), Society for Professional Journalists (SPJ), Radio and Television News Directors Association (RTNDA), and others—have included greater ethnic diversity as a primary goal or ethic. However, progress has been slow. ASNE has set 2025 as a target date to have minority representation in newsrooms match U.S. demographics.[21]

Because the programming about, by, and for ethnic minorities in the mainstream media is disproportionately low, many turn to niche publications and channels such as BET, Univision, Telemundo, Essence, Jet, and others for sources of information and entertainment. In fact, 45 percent of ethnic-minority adults prefer these niche media sources to mainstream television, radio programs, and newspapers.[22] These sources cover stories about racial minorities that are generally ignored by the mainstream press and offer ethnic-minority perspectives on more widely covered issues in the news.[23] It is possible for people who are not minorities to use their privilege to fight for equality and spread awareness. By being exposed to and learning of the hardships that minorities and the LGBTQ community have faced, others will recognize their role in supporting them and engaging in forms of activism.[24] Entertainment channels like BET (a 24-hour cable television station that offers music videos, dramas featuring predominantly Black casts, and other original programming created by African Americans) provide the diverse programming that mainstream TV networks often drop.[25] Print sources like Vista, a bilingual magazine targeting U.S. Hispanics, and Vivid, the most widely circulated African American periodical, appeal to ethnic minority groups because they are controlled and created by individuals within these groups. Though some criticize ethnic niche media, claiming that they erode common ground or, in some instances, perpetuate stereotypes, the popularity of these media has only grown in recent years and will likely continue in the absence of more diverse perspectives in mainstream media sources.[26],[27]

Femininity in Mass Media

In the ABC sitcom The Donna Reed Show (1958–1966), actress Donna Reed plays a stay-at-home mother who fills her days with housework, cooking for her husband and children, decorating, and participating in community organizations, all while wearing pearls, heels, and stylish dresses. Such a traditional portrayal of femininity no doubt sounds dated to modern audiences, but stereotyped gender roles continue to thrive in the mass media. Women are still often represented as subordinate to their male counterparts—emotional, non-competitive, domestic, and sweet-natured. These expectations and representations can impact the career opportunities that both men and women can receive. For example, mothers are approximately two times less likely to be recommended for a job than childless women, while men don’t receive any changes in their likability.[28] In contrast to these types, other women are represented as unattractively masculine, crazy, or cruel. In TV dramas and sitcoms, women continue to fill traditional roles such as mothers, nurses, secretaries, and housewives. By contrast, men in film and television are less likely to be shown in the home, and male characters are generally characterized by dominance, aggression, action, physical strength, and ambition.[29] In the mainstream news media, men are predominantly featured as authorities on specialized issues like business, politics, and economics, while women are more likely to report on stories about natural disasters or domestic violence—coverage that does not require expertise.[30] These “characteristics” of men and women can be seen as a kernel of truth underlying gender stereotypes. A kernel of truth is the core accuracy and main point of a claim or narrative that contains fictitious elements, such as not accounting for the far-reaching inferences that are made about more essential and factual differences between men and women.[31]

Not only is the white male perspective still presented as the standard, authoritative one, but also the media itself often comes to embody the male gaze. Media commentator Nancy Hass notes that “shows that don’t focus on men have to feature the sort of women that guys might watch.”[32] Men often claim that their ideal romantic partner is someone who is as intelligent as or more intelligent than they are despite appearing less attracted to a woman who outsmarts them. Despite claiming to value assertive and independent women, it is assumed that men will be more attracted to women with accommodating and agreeable behaviors.[33] Feminist critics have long been concerned by the way women in film, television, and print media are defined by their sexuality. Few female role models exist in the media who are valued primarily for qualities like intelligence or leadership. Inundated by images that conform to unrealistic beauty standards, women come to believe at an early age that their value depends on their physical attractiveness. According to one Newsweek article, eating disorders in girls are now routinely being diagnosed at younger ages, sometimes as early as eight or nine. The models who appear in magazines and print advertising are unrealistically skinny (23 percent thinner than the average woman), and their photographs are further enhanced to hide flaws and blemishes. Meanwhile, the majority of women appearing on television are under the age of 30, and many older actresses, facing the pressure to embody the youthful ideal, undergo surgical enhancements to appear younger.[34] One recent example is TV news host Greta Van Susteren, a respected legal analyst who moved from CNN to Fox in 2002. At the debut of her show, On the Record, Van Susteren, sitting behind a table that allowed viewers to see her short skirt, had undergone not only a hair and wardrobe makeover, but also surgical enhancement to make her appear younger and more attractive.[35]

In addition to the prevalence of gender stereotypes, the ratio of men to women in the mass media, in and behind the scenes, is also disproportionate. Surprisingly, though women slightly outnumber men in the general population, over two-thirds of TV sitcoms feature men in the starring role.[36] Among writers, producers, directors, and editors, the number of women lags far behind. In Hollywood, for instance, only 17 percent of behind-the-scenes creative talent is represented by women. Communications researcher Martha Lauzen argues that “when women have more powerful roles in the making of a movie or TV show, we know that we also get more powerful female characters on-screen, women who are more real and more multi-dimensional.”[37] The best way to learn from these stereotypes and move on for better representation is for people to acknowledge and re-evaluate the nature of different social roles, educate others on the description and controversies of stereotypes, and support everyone equally and not treat anyone with a disadvantage.[38]

Sexual Content in Public Communication

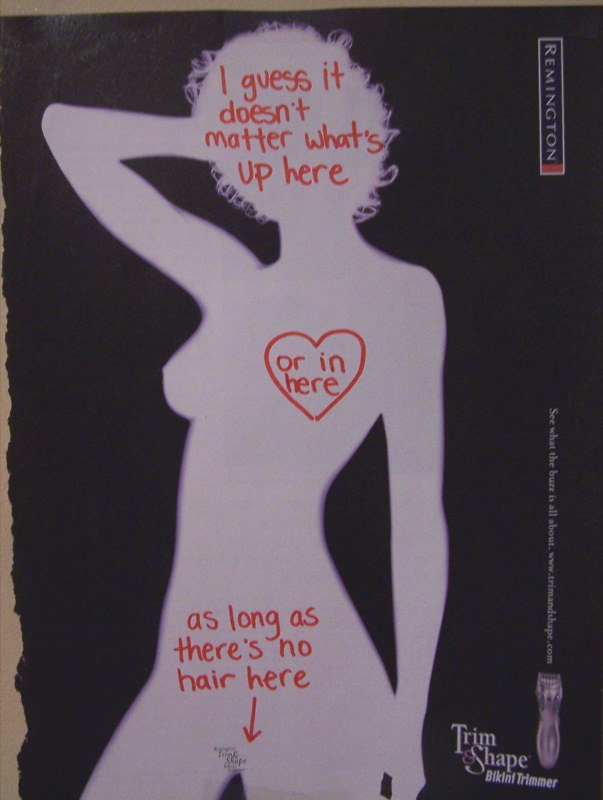

Creators of all forms of media know that sex—named, innuendoed, or overtly displayed—is a surefire way to grab an audience’s attention. “Sex sells” is an advertising cliché; the list of products that advertisers have linked to erotic imagery or innuendo, from cosmetics and cars to vacation packages and beer, is nearly inexhaustible. Most often, sexualized advertising content is served up in the form of the female body, in part or in whole, featured in provocative or suggestive poses beside a product that may have nothing to do with sexuality. However, by linking these two things, advertisers are marketing desire itself.

Sex is used to sell not just consumer goods; it sells media, too. Music videos on MTV and VH1, which promote artists and their music, capture audience attention with highly suggestive dance moves, often performed by scantily clad women. Movie trailers may flash brief images of nudity or passionate kissing to suggest more to come in the movie. Video games feature female characters like Lara Croft of Tomb Raider, whose tightly fitted clothes reveal all the curves of her Barbie-doll figure. An experimental study reported that teens who were persuaded into playing video games with highly sexualized female characters showed diminished self-efficiency.[39] And partially nude models grace the cover of men’s and women’s magazines like Maxim, Cosmopolitan, and Vogue where cover lines promise titillating tips, gossip, and advice on bedroom behavior.[40] Most male models are portrayed with more imagery of the face and upper body while most female models have full body images, facilitating the tendency to evaluate a woman based on her dress style and body shape.[41]

In the 1920s and 1930s, filmmakers attracted audiences to the silver screen with the promise of what was then considered scandalous content. Prior to the 1934 Hays Code, which placed restrictions on “indecent” content in movies, films featured erotic dances, male and female nudity, references to homosexuality, and sexual violence. D. W. Griffith’s Intolerance (1916) includes scenes with topless actresses, as does Ben Hur (1925). In Warner Bros.’ Female (1933), the leading lady, the head of a major car company, spends her evenings in sexual exploits with her male employees, a storyline that would never have passed the Hays Code a year later.[42] Trouble in Paradise, a 1932 romantic comedy, was withdrawn from circulation after the institution of the Hays Code because of its frank discussion of sexuality. Similarly, Dr. Jekyll and Mr. Hyde (1931), which featured a prostitute as one of the main characters, was also banned under the code.[43]

In the 1960s, when the sexual revolution led to increasingly permissive attitudes toward sexuality in American culture, the Hays Code was replaced with the MPAA rating system. The rating system, designed to warn parents about potentially objectionable material in films, allowed filmmakers to include sexually explicit content without fear of public protest. Since the replacement of the Hays Code, sexual content has been featured in movies with much greater frequency.

The problem, according to many media critics, is not that sex now appears more often but that it is almost always portrayed unrealistically in American mass media.[44] This can be harmful, they say, because the mass media are important socialization agents–that is, ways that people learn about the norms, expectations, and values of their society.[45] Sex, as many films, TV shows, music videos, and song lyrics present it, is frequent and casual. Rarely do these media point out the potential emotional and physical consequences of sexual behavior. According to one study, portrayals of sex that include possible risks like sexually transmitted diseases or pregnancy only occur in 15 percent of the sexually explicit material on TV.[46] Additionally, actors and models depicted in sexual relationships in the media are thinner, younger, and more attractive than the average adult. This creates unrealistic expectations about the necessary ingredients for a satisfying sexual relationship.

Social psychologists are particularly concerned with the negative effects these unrealistic portrayals have on women, as women’s bodies are the primary means of introducing sexual content into media targeted at both men and women. Media activist Jean Kilbourne points out that “women’s bodies are often dismembered into legs, breasts or thighs, reinforcing the message that women are objects rather than whole human beings.” Adbusters, a magazine that critiques mass media, particularly advertising, points out the sexual objectification of women’s bodies in a number of its spoof advertisements, such as the one in the figure below, bringing home the message that advertising often sends unrealistic and harmful messages about women’s bodies and sexuality. Additionally, many researchers note that in women’s magazines, advertising, and music videos, women are often implicitly—and sometimes explicitly—given the message that a primary concern should be attracting and sexually satisfying men.[47] Furthermore, the recent increase in entertainment featuring sexual violence may, according to some studies, negatively affect the way young men behave toward women.[48]

These negative behaviors can also lead to the topic of rape culture. Though young men, especially gay men, can be victims of sexual harassment, women tend to get the most spotlight when discussing rape culture and have fought hard to make their voices heard, and rape education and activism has recently increased in the early 2020s, with students learning consent training and the slogans “consent is sexy” and “sex without consent is rape” being heavily pushed and popularized especially on social media to fill the absence of empirical research discussing the concept of consent and rape convention.[49]

Young women and men are especially vulnerable to the effects of media portrayals of sexuality. Psychologists have long noted that teens and children get much of their information and many of their opinions about sex through TV, film, and online media. In fact, two-thirds of adolescents turn to the media first when they want to learn about sexuality.[50] The media may help shape teenage and adolescent attitudes toward sex, but they can also lead young people to engage in sexual activity before they are prepared to handle the consequences. According to one study, kids with high exposure to sex on television were almost twice as likely to initiate sexual activity compared to kids without exposure.[51]

Cultural critics have noted that sexually explicit themes in mass media are generally more widely accepted in European nations than they are in the United States. However, the increased concern and debates over censorship of sexual content in the United States may in fact be linked to the way sex is portrayed in American media rather than to the presence of the sexual content in and of itself. Unrealistic portrayals that fail to take into account the actual complexity of sexual relationships seem to be a primary concern. As Jean Kilbourne has argued, sex in the American media “has far more to do with trivializing sex than with promoting it. We are offered a pseudo-sexuality that makes it far more difficult to discover our own unique and authentic sexuality.”[52] However, despite these criticisms, it is likely that unrealistic portrayals of sexual content will continue to be the norm in mass media unless the general public stops consuming these images.

Key Takeaways

- In American mass media, where the White male perspective is still presented as the standard, stereotypes of those who differ—women, ethnic minorities, and gays and lesbians—are an issue of ethical concern.

- Racial minorities are often absent, peripheral, or stereotyped in film, television, print media, advertising, and video games.

- Racial stereotypes occur in news reporting, where they influence public perceptions.

- Underrepresentation of women and racial and ethnic minorities is also a problem in the hiring of creative talent behind the scenes.

- The media still often subordinate women to traditional roles, where they serve as support for their male counterparts.

- The objectification of women in various visual media has particularly led to concerns about body image, unrealistic social expectations, and negative influences on children and adolescent girls.

- “Sex sells” consumer products and media such as movies and music videos.

- The issue of sexual content in the media has become a source of concern to media critics because of the frequency with which it occurs and also because of the unrealistic way it is portrayed.

Exercises

Choose a television show or movie you are familiar with and consider the characters in terms of racial and gender diversity. Then answer the following short-answer questions. Each response should be one to two paragraphs.

- Does the show or movie you’ve chosen reflect racial and gender diversity? Why or why not? Explain why this kind of diversity is important in media.

- Are there any racial or gender stereotypes present in the show or movie you’ve chosen? If so, identify them and describe how they are stereotypical. If not, describe what elements would prevent the portrayal of female or ethnic minority characters from being stereotypical.

- Does the show or movie you’ve selected feature any sexual content? If so, do you think that the content is gratuitous or unrealistic, or does it serve the story? Explain your answer. Then explain why the use of sexual content in media is a concern for many media critics.

- Watch segments of the evening news on three major television networks. Based on the information presented here about representations of women and racial minorities, what do you observe? Do your observations corroborate claims of stereotyping and underrepresentation? Do you notice important differences among the three networks regarding these issues?

- Create a mock advertisement that breaks with common racial stereotypes, gender myths, or media representations of sexuality.

Media Attributions

- A-SKIN-YOU-LOVE-TO-TOUCH © By A.J.Co.(Life time: na (--work for hire for Andrew Jergens Co, Cincinnati) - Original publication: 1916 Ladies' Home Journal vol 33#9Immediate source: https://s-media-cache-ak0.pinimg.com/736x/fe/d0/39/fed039a2362769617cfcd50f648aa22e.jpghttps://i1.wp.com/ilymag.com/wp-content/uploads/2018/12/a81ffb1a04098534ef955ba6fff4c31a.jpg?fit=10001382&ssl=1 images, Public Domain, https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=44103795 is licensed under a Public Domain license

- Adbust © Chelsea K via. Flickr is licensed under a CC BY-NC (Attribution NonCommercial) license

- Burr, Sherri. “Television and Societal Effects: An Analysis of Media Images of African-Americans in Historical Context,” Journal of Gender, Race and Justice 4 (2001): 159. ↵

- U.S. Census Bureau, “2010 Census Data,” https://web.archive.org/web/20101216004858/http://2010.census.gov/2010census/data/. ↵

- Tukachinsky Forster, Rebecca (Riva); Neuville, Caitlin; Foucaut, Sixtine; Morgan, Sara; Poerschke, Angela; Torres, Andrea. “Media Users as Allies: Personality Predictors of Dominant Group Members’ Support for Racial and Sexual Diversity in Entertainment Media,” The Communication Review (2022): 56 ↵

- Ellemers, Naomi. “Gender Stereotypes,” Annual Review of Psychology (2018): 276 ↵

- ibid, 282 ↵

- Hearne, Joanna. “Hollywood Whiteness and Stereotypes,” Film Reference, http://www.filmreference.com/encyclopedia/Independent-Film-Road-Movies/Race-and-Ethnicity-HOLLYWOOD-WHITENESS-AND-STEREOTYPES.html. ↵

- Tukachinsky Forster, Rebecca (Riva); Neuville, Caitlin; Foucaut, Sixtine; Morgan, Sara; Poerschke, Angela; Torres, Andrea. “Media Users as Allies: Personality Predictors of Dominant Group Members’ Support for Racial and Sexual Diversity in Entertainment Media,” The Communication Review (2022): 56 ↵

- Baynes, Leonard M. “White Out: The Absence and Stereotyping of People of Color by the Broadcast Networks in Prime Time Entertainment Programming,” Arizona Law Review 45 (2003): 293. ↵

- WWAY, “NAACP Not Pleased With the Diversity on Television,” January 12, 2009, https://web.archive.org/web/20130731085203/http://www.wwaytv3.com:80/naacp_not_pleased_diversity_television/01/2009. ↵

- Tukachinsky Forster, Rebecca (Riva); Neuville, Caitlin; Foucaut, Sixtine; Morgan, Sara; Poerschke, Angela; Torres, Andrea. “Media Users as Allies: Personality Predictors of Dominant Group Members’ Support for Racial and Sexual Diversity in Entertainment Media,” The Communication Review (2022): 56 ↵

- Media Awareness Network, “Ethnic and Visible Minorities in Entertainment Media,” 2010, https://web.archive.org/web/20120506072517/http://www.media-awareness.ca:80/english/issues/stereotyping/ethnics_and_minorities/minorities_entertainment.cfm. ↵

- Tukachinsky Forster, Rebecca (Riva); Neuville, Caitlin; Foucaut, Sixtine; Morgan, Sara; Poerschke, Angela; Torres, Andrea. “Media Users as Allies: Personality Predictors of Dominant Group Members’ Support for Racial and Sexual Diversity in Entertainment Media,” The Communication Review (2022): 62 ↵

- Baynes, Leonard M. “White Out: The Absence and Stereotyping of People of Color by the Broadcast Networks in Prime Time Entertainment Programming,” Arizona Law Review 45 (2003): 293. ↵

- Burr, Sherri. “Television and Societal Effects: An Analysis of Media Images of African-Americans in Historical Context,” Journal of Gender, Race and Justice 4 (2001): 159. ↵

- Gents, Natascha and Kramer, Stefan. “Globalization, Cultural Identities and Media Representations,” Albany: State University of New York Press (2006): 99 ↵

- Media Awareness Network, “Ethnic and Visible Minorities in the News,” 2010, https://web.archive.org/web/20120510135709/http://www.media-awareness.ca:80/english/issues/stereotyping/ethnics_and_minorities/minorities_news.cfm. ↵

- National Association of Hispanic Journalists, “NAHJ Disturbed by Figures That Mask Decline in Newsroom Diversity,” news release, 2010, https://web.archive.org/web/20140326074551/http://www.nahj.org/nahjnews/articles/2008/April/ASNE.shtml. ↵

- Christians, Clifford G. “Communication Ethics,” in Encyclopedia of Science, Technology, and Ethics, ed. Carl Mitchum (Detroit: Macmillan Reference USA, 2005), 1:366. ↵

- Media Awareness Network, “Ethnic and Visible Minorities in the News,” 2010, https://web.archive.org/web/20120510135709/http://www.media-awareness.ca:80/english/issues/stereotyping/ethnics_and_minorities/minorities_news.cfm. ↵

- Whitehouse, Ginny. “Why Diversity Is an Ethical Issue,” The Handbook of Mass Media Ethics, ed. Lee Wilkins and Clifford G. Christians (New York: Routledge, 2009), 101. ↵

- ibid, 102. ↵

- ibid ↵

- State of the Media, Pew Project for Excellence in Journalism, “Ethnic,” in The State of the News Media 2010, https://www.issuelab.org/resources/11239/11239.pdf. ↵

- Tukachinsky Forster, Rebecca (Riva); Neuville, Caitlin; Foucaut, Sixtine; Morgan, Sara; Poerschke, Angela; Torres, Andrea. “Media Users as Allies: Personality Predictors of Dominant Group Members’ Support for Racial and Sexual Diversity in Entertainment Media,” The Communication Review (2022): 66 ↵

- Zellars, Rachel. “Black Entertainment Television (BET),” in Encyclopedia of African-American Culture and History, 2nd ed., ed. Colin A. Palmer (Detroit: Macmillan Reference USA, 2006.) 1:259. ↵

- Tran, Can. “TV Network Reviews: Black Entertainment Television (BET),” Helium, https://web.archive.org/web/20130717033153/http://www.helium.com:80/items/884989-tv-network-reviews-black-entertainment-television-bet. ↵

- Flint, Joe. “No Black-and-White Answer for the Lack of Diversity on Television,” Company Town (blog), Los Angeles Times, June 11, 2010, http://latimesblogs.latimes.com/entertainmentnewsbuzz/2010/06/diversity-television.html. ↵

- Ellemers, Naomi. “Gender Stereotypes,” Annual Review of Psychology (2018): 281 ↵

- Chandler, Daniel. “Television and Gender Roles” https://homepages.dsu.edu/huenersd/engl101/final exam/chandler.htm. ↵

- Media Awareness Network, “Media Coverage of Women and Women’s Issues,” https://web.archive.org/web/20120509210400/http://www.media-awareness.ca:80/english/issues/stereotyping/women_and_girls/women_working.cfm. ↵

- Ellemers, Naomi. “Gender Stereotypes,” Annual Review of Psychology (2018): 277 ↵

- Media Awareness Network, “The Economics of Gender Stereotyping,” https://web.archive.org/web/20120426152609/http://www.media-awareness.ca:80/english/issues/stereotyping/women_and_girls/women_economics.cfm. ↵

- Ellemers, Naomi. “Gender Stereotypes,” Annual Review of Psychology (2018): 281 ↵

- Derenne, Jennifer L. and Eugene V. Beresin, “Body Image, Media, and Eating Disorders,” Academic Psychiatry 30 (2006), https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/16728774/. ↵

- Media Awareness Network, “Media Coverage of Women and Women’s Issues,” https://web.archive.org/web/20120509210400/http://www.media-awareness.ca:80/english/issues/stereotyping/women_and_girls/women_working.cfm. ↵

- Media Awareness Network, “Women Working in the Media,” https://web.archive.org/web/20120509210400/http://www.media-awareness.ca:80/english/issues/stereotyping/women_and_girls/women_working.cfm. ↵

- ibid ↵

- Ellemers, Naomi. “Gender Stereotypes,” Annual Review of Psychology (2018): 292 ↵

- Ellemers, Naomi. “Gender Stereotypes,” Annual Review of Psychology (2018): 284 ↵

- Reichert, Tom and Jacqueline Lambiase, “Peddling Desire: Sex and the Marketing of Media and Consumer Goods,” Sex in Consumer Culture: The Erotic Content of Media and Marketing, ed. Tom Reichert and Jacqueline Lambiase (New York: Routledge, 2005), 3. ↵

- Ellemers, Naomi. “Gender Stereotypes,” Annual Review of Psychology (2018): 284 ↵

- Morris, Gary. “Public Enemy: Warner Brothers in the Pre-Code Era,” Bright Lights Film Journal, September 1996, http://www.brightlightsfilm.com/17/04b_warner.php. ↵

- Signorelli, Priscilla. “30 Essential Films For An Introduction To Pre-Code Hollywood.” Taste of Cinema - Movie Reviews and Classic Movie Lists (blog), November 29, 2015. https://www.tasteofcinema.com/2015/30-essential-films-for-an-introduction-to-pre-code-hollywood/. ↵

- Galician, Mary Lou. Sex, Love & Romance in the Mass Media (New York: Routledge, 2004), 5 ↵

- ibid, 82. ↵

- Parents Television Council, “Facts and TV Statistics,” https://web.archive.org/web/20160117111846/http://www.parentstv.org/PTC/facts/mediafacts.asp. ↵

- ibid ↵

- Gunter, Barrie. Media Sex: What Are the Issues? (Mahwah, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates, 2002), 8. ↵

- Dale, Catherine; Overell, Rosemary. “Orienting Feminism: Media, Activism, and Cultural Representation,” Cham: Springer International Publishing (2018): 181 ↵

- Media Awareness Network, “Sex and Relationships in the Media,” Media Awareness Network, https://web.archive.org/web/20120521174258/http://www.media-awareness.ca:80/english/issues/stereotyping/women_and_girls/women_sex.cfm. ↵

- Collins, Rebecca L. and others, “Watching Sex on Television Predicts Adolescent Initiation of Sexual Behavior,” Pediatrics 114, no. 3 (2004), https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/15342887/ ↵

- Media Awareness Network, “Sex and Relationships in the Media,” Media Awareness Network, https://web.archive.org/web/20120521174258/http://www.media-awareness.ca:80/english/issues/stereotyping/women_and_girls/women_sex.cfm. ↵