8.1 Historical and Technological Developments

Learning Objectives

- Understand the historical development of telecommunication technologies, from the early experiments with electrical telegraphs to the invention and adoption of the telephone.

- Analyze the social, political, and economic factors that influenced the adoption of telecommunication technologies, including their impact on the Civil War and the deaf community.

- Evaluate the contributions and controversies surrounding key figures in the development of telecommunication, such as Samuel Morse, Alexander Graham Bell, and Thomas Edison, and their lasting impact on modern communication systems.

Early Development

Before the telegraph became a household name, several individuals dabbled in the field of electrical communication. Harrison Gray Dyar was one of the earliest experimenters, successfully conducting tests in 1826-27. However, he eventually abandoned his pursuits. Similarly, David Alter of Pennsylvania developed a rudimentary electrical telegraph system in 1836 but failed to commercialize it. These early endeavors laid the groundwork for what would become a revolution in communication.

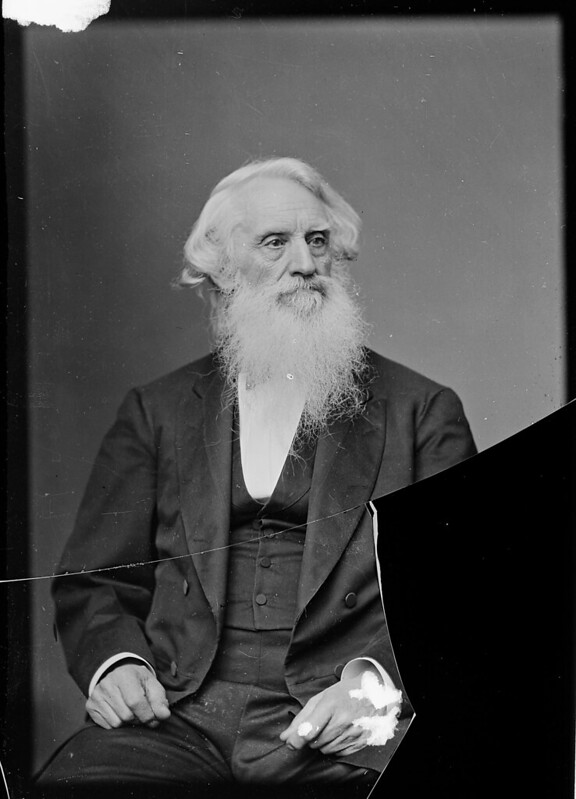

Samuel Morse, a name synonymous with the telegraph, entered the scene in the late 1830s. He employed Alfred Vail in September 1837 to refine his telegraph system. Vail’s engineering skills were instrumental in transforming Morse’s prototype into a more practical device. That same month, Morse filed for a patent, officially marking his entry into the telegraphy arena.

Morse’s first public demonstration was at Speedwell Ironworks in New Jersey on January 6, 1838. The event garnered significant attention and even involved a presentation to President Martin Van Buren. Despite this, Morse faced legislative hurdles. A proposal by Congressman Francis Ormand Jonathan Smith to allocate $30,000 for Morse’s telegraph was rejected by Congress in April 1838. Undeterred, Morse continued his work and finally secured a patent on June 20, 1840.

The U.S. Congress finally saw the potential of Morse’s invention and allocated funds on March 3, 1843, for a telegraph line between Washington, D.C., and Baltimore. Initially, Morse planned to lay the wire underground, but the project faced numerous setbacks. Learning from the work of William Fothergill Cooke and Charles Wheatstone’s success in England with pole-based lines, Morse decided to switch tactics.

Work on the pole-based line began in earnest on April 1, 1844. The construction used chestnut poles of seven meters in height, spaced 60 meters apart. The first test message was sent on May 1, 1844, conveying news of Henry Clay’s nomination for U.S. President. Morse’s famous message, “What hath God wrought!” was transmitted on May 24, 1844, marking a monumental moment in the history of communication.

The first public telegraph office opened in Washington, D.C., on April 1, 1845, under the control of the Postmaster-General. This marked the beginning of commercial telegraphy, as the public now had to pay for messages. By the end of 1846, telegraph lines had expanded significantly, connecting major cities like Washington, Boston, Pittsburgh, New York, Albany, and Buffalo. The expansion was so rapid that by the end of the decade, lines had even reached Toronto and Montreal in Canada.

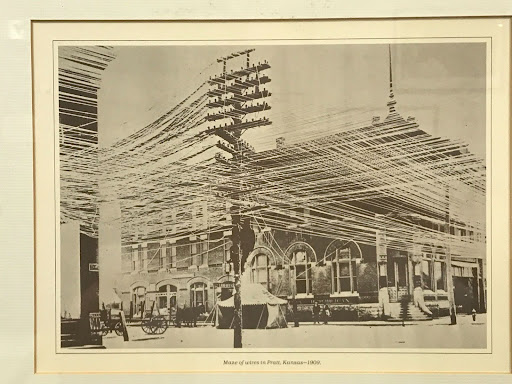

By 1850, the United States had about 12,000 miles of telegraph lines operated by 20 different companies. Western Union was organized in 1851, and it would later become one of the most significant players in the telegraph industry. The 1850s also saw the telegraph reach the West Coast, including cities like San Francisco, San Jose, Stockton, Sacramento, and Marysville.

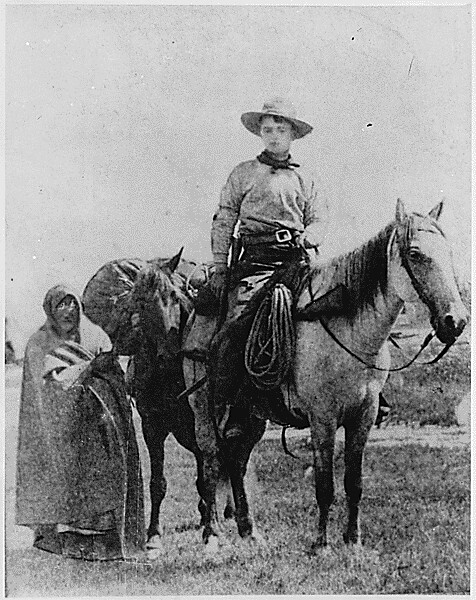

The dream of a transcontinental telegraph line became a reality in 1861. Work began on July 4, and the line was completed on October 24 at Salt Lake City, Utah. This achievement rendered the Pony Express obsolete and connected the two coasts of the United States for the first time.

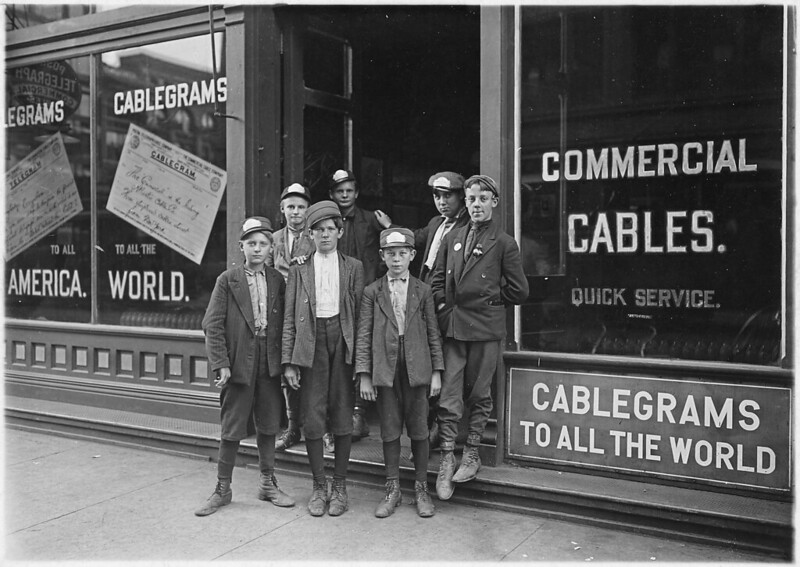

Although the Pony Express was no longer needed, the way the telegraph functioned still required humans to help transmit the messages to their destination. The message transmitted via telegraph would be deciphered into letters that were printed on a telegraph, and the telegram was then delivered to its local addressee. This work was often done by children.

The first transatlantic telegraph cable was laid on August 16, 1858, but failed after just three weeks. It wasn’t until July 18, 1866, that a reliable new cable was successfully laid. By the 1870s, telegraph lines had reached as far as India and Australia, making it a truly global communication network.

By this point in time, Morse was making relatively little from the patent rights he held for the telegraph. In the U.S., the demand for telegraphy service led to the founding of a wide variety of telegraph companies, and many of these companies produced their own variations of devices that could be used to transmit messages. These variations allowed the filing of new patents that didn’t require the licensing of Morse’s original patent. While European countries recognized Morse as the inventor of the telegraph, he never actually filed for patents in any countries outside of the U.S., even though he traveled in Europe significantly to promote his work. Therefore, he received no royalties outside the U.S.[1]

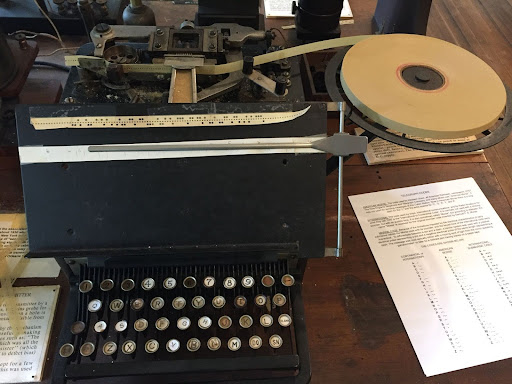

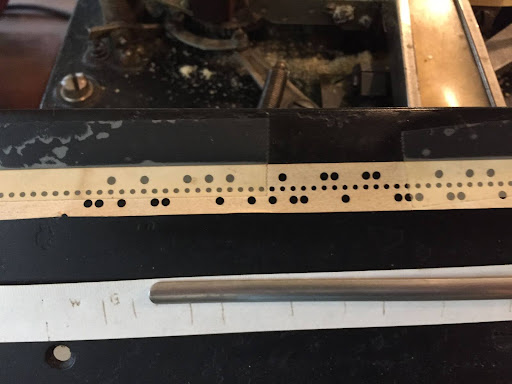

The demand for telegraph services helped drive significant innovation. In 1858, Wheatstone secured a patent for an automatic sender, which could transmit messages at 400 words per minute – ten times faster than existing human operators! The automatic transmission used pre-punched tape to transmit the message. Although a human hand was still needed to create these pre-punched tapes, this unskilled labor could be paid for at one-fourth of the salary demanded by human telegraph operators. Sending more words per minute also helped increase the volume of information that could be transmitted across a line, with a trickle-down effect on how people paid for sending telegrams – rather than paying by the word, they could now pay by the length of tape used.[2]

The Civil War and Beyond

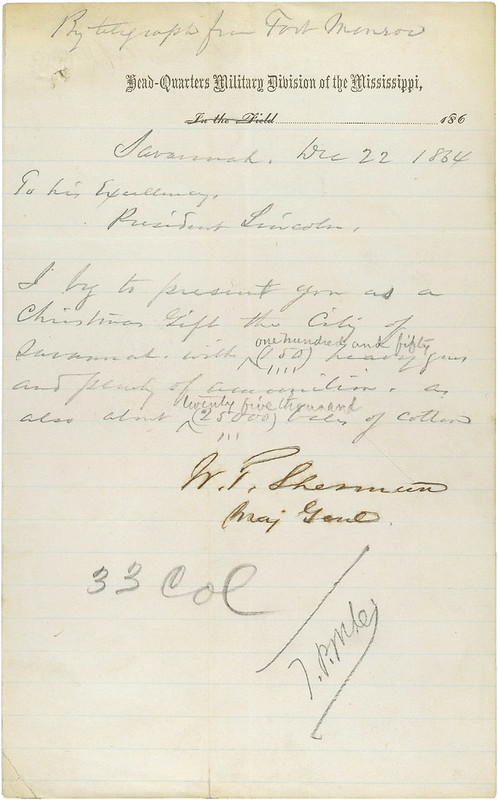

Tom Wheeler offers an in-depth analysis of how the telegraph impacted the Civil War in his book, Mr. Lincoln’s T-Mails: The Untold Story of How Abraham Lincoln Used the telegraph to win the Civil War.[3] The telegraph emerged as a transformative technology during the Civil War, offering a significant advantage to the Union army, which was electronically interconnected far more than their Rebel opponents. This innovative technology allowed for rapid communication across vast distances, transforming the way leadership was exercised and military operations were conducted.

Abraham Lincoln, the Union’s President, was an early adopter of the telegraph. He recognized and embraced its potential as a tool to impose his leadership, manage military strategy, and keep abreast of developments on the battlefield in real-time. Lincoln’s use of the telegraph was groundbreaking; it not only expedited the delivery of messages but enabled a virtual conversation occurring in near real-time between parties separated by large distances. This marked a significant shift in the nature of national executive leadership and provided Lincoln with a tool that played a crucial role in the Union’s victory in the Civil War.

In the mid-19th-century world, where electricity was barely understood, the concept of sending messages via electric pulses was revolutionary, and the acceptance of this technology varied greatly. Wheeler writes:

It was easier for a member of Congress in the 1960s to comprehend placing a man on the moon than it was for his or her counterpart in the 1840s to grasp the concept of sending messages by electric sparks.[4]

Northern states, which were more inclined toward embracing innovation, utilized the telegraph to their advantage. It became an integral part of their military and strategic operations, greatly enhancing their efficiency and efficacy.

The telegraph also played a significant role in conjunction with the railway system. Railroads provided free rights of way along their tracks to telegraph companies that, in turn, carried railroad traffic as priority and for free. This symbiotic relationship led to improvements in both railroad and telegraph system efficiencies, further contributing to the strategic advantage of the Union. In contrast, Southern states, fearing the impact of these innovations on their traditional way of life, resisted the implementation of the telegraph and the railway system. This resistance limited their electronic infrastructure and the expansion of their communication networks during the war, placing them at a disadvantage.

In addition to its military application, the telegraph also influenced information control and censorship during the war. The administration reached an understanding with wire services, which were favored as the outlet of choice, but with the expectation that they would report stories as the government wanted. To safeguard important transmissions, both sides developed cipher codes, adding another layer of complexity to wartime communication.

In the face of challenges and setbacks, Lincoln’s use of the telegraph proved instrumental in maintaining control and direction. He demonstrated a profound understanding of this new technology and used it effectively to guide the Union’s strategy. The telegraph, coupled with Lincoln’s leadership, played a significant role in the Union’s victory in the Civil War. Lincoln’s adoption and effective use of the telegraph represented a stunning breakthrough, particularly in a world where electricity was an abstract concept and no national figure had ever used electronic messages in the exercise of their leadership:

It was how Lincoln used the traffic coming from the other direction—the inbound reports, including those not addressed to him—that broke new ground. By reviewing the contents of the telegraph clerk’s drawer “down to the raisins,” the president turned the telegraph into a window on activities spread over a vast geographic area and an insight into the thinking at his generals’ headquarters.[5]

His ability to harness this new technology for leadership and strategic advantage was nothing short of inspired. Lincoln’s strategic application of the telegraph set a precedent for the use of technology in leadership, a legacy that continues to resonate in today’s digital age.

The use of the telegraph and related technology extended into future wars as well. For example, World War I featured telegraph battalions. Fort Devens (then Camp Devens), in Devens, MA was home to the 401st telegraph battalion.

Even as the telegraph waned in popularity with regular citizens, the skills associated with its technology remained important for the military. Fort Devens served as a central training location for these skills through the 1970s.

Fort Devens hosted the United States Army Security Agency Training Center and School from 1951 until 1976. ASA training included virtually every facet of electronic and signals intelligence. LInguists, Morse intercept operators, teletype and voice intercept operators, cryptographers, and direction finding equipment operators were trained here. From Fort Devens, ASA personnel were sent to detachments across the globe. Many of their missions remain classified to this day. On January 1, 1977, the ASA was replaced by the U.S. Army INtelligence and Security Command. For countless ASA veterans, For Devens was where they learned to be “Vigilant Always.”[6]

From Text to Voice

The technology that was at the core of the telegraph slowly developed into what would become the telephone as inventors continued to experiment with new ways to send an even greater volume of messages across wires. The 1870s saw significant technological advancements in telegraphy. Duplex systems, introduced in 1871, allowed two messages to be sent over a single wire at the same time but in opposite directions. Thomas Edison took this a step further with his invention of the quadruplex telegraph in 1874, which allowed four separate signals to be transmitted and received on a single wire simultaneously.

Work on transmitting voice over these wires began as early as 1849, with Italian immigrant Antonio Meucci, who created a device to transmit audio between his workshop and the bedroom of his disabled wife, Esther, on the third floor of their cottage. He began installing the device in 1854 and achieved success by 1856.[7] A German inventor, Philipp Reis, also invented a version of the telephone in 1861. This device captured audio, converted it to electrical pulses that were transmitted over a wire, and then converted them back into audio at the other end.[8] However, neither of these inventors ever received a patent for their work.[9]

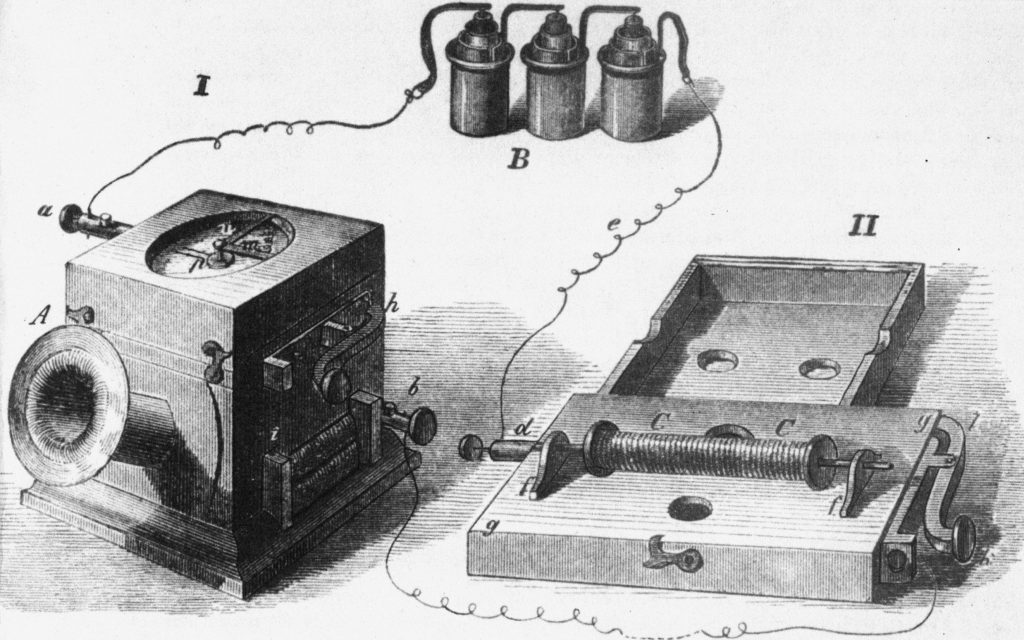

Alexander Graham Bell and Elisha Gray both made filings with the patent office on the same day, Monday, February 14, 1876. Gray had filed a patent caveat, or provisional patent application meant to block other inventors from submitting a similar patent for a period of one year. However, Bell filed his patent on the same day, even though it was not yet fully working. Bell’s patent was apparently reviewed first, awarding him the patent, however, if Gray’s caveat had been reviewed first, Bell’s patent would have been blocked.[10] Both men were working toward the invention of a harmonic telegraph that was intended to expand the capacity of telegraph lines. Unlike Meucci and Reis, the ability to transmit voice was an unexpected consequence of this work. The plan for this device was to use a series of reeds that would oscillate at the same frequency, generating electrical signals that would be transmitted across the telegraph line. Identical reeds at the other end could receive the signal transmitted by its twin and produce a series of dots and dashes. This system would allow for the transmission of multiple messages at the same time, with a unique message communicated by each reed with a unique frequency.[11]

Controversy lingers over who should receive the credit for being first to invent the telephone. In 2001, the U.S. Congress passed a resolution that credits Antonio Meucci as the inventor, but Canada’s House of Commons responded by passing a motion recognizing Alexander Graham Bell.[12]

Bell’s first breakthrough came on June 2, 1875. One of the reeds became lodged and Bell’s assistant, Thomas Watson, pulled it with greater force than usual to dislodge it. This resulted in Bell hearing a unique twang of the reed at his end of the wire, a sound far more intricate than the rudimentary musical tones his device was designed to transmit. This incident sparked an insight in Bell, leading him to the realization that his device could be modified to transport any sounds, including human voices, over a wire.[13] But it was his significant work up to this point that allowed him to understand the importance of this accident:

Pasteur once wrote “Chance favors the prepared mind,” and this incident, when Nature left the door to her secrets ajar for one instant, confirms his insight. Bell’s vague, dreamy notion of how sound might be mirrored by an undulating electrical current, his hyper-normal sense of hearing, and the months of utter concentration which him habitually and unconsciously press the reed-magnet to his ear, all combined to let him see the significance of an “accident” as though illuminated by a bolt of lighting. He knew what had happened even though it would take him many hours to articulate in words for others.[14]

Based on this work, Bell filed his patent in February of 1876. Another breakthrough occurred by accident on March 10th, 1876. This time, the breakthrough was inspired by Bell’s controversial involvement with the deaf community.

Bell’s Controversial Work with the Deaf Community

Bell’s father had created the “Visible Speech” technique for instructing the deaf, and his grandfather was a distinguished speech teacher. Bell applied his father’s approach in several educational settings, including the Boston School for Deaf Mutes and the American Asylum for the Deaf. His own life experiences, such as having a mother with hearing loss and a wife who was both his former student and deaf, had a profound impact on his work.[15]

Bell’s expertise made him a natural choice for advising the Census Bureau. As early as 1889, he began making recommendations for more accurate and sensitive enumeration of people with hearing and speech disabilities. Appointed as “Expert Special Agent of the Census Office” in 1900, Bell was responsible for designing the supplemental questionnaire for the census, which for the first time included carefully phrased questions to assess varying degrees of disabilities. The resulting report, though not completed until 1906, offered the most comprehensive data on the deaf, blind, and those with speech impairments up to that time. Bell’s nuanced understanding of disability and his sensitive approach to questioning had a long-lasting impact, laying the foundation for modern census methodology that recognizes various disabilities, including cognitive and ambulatory difficulties. Despite the stress the census work inflicted on him, as noted by his wife, Mabel, Bell’s contributions to this field were pioneering and left an enduring legacy.[16] In addition to this work on the census, he also created an audiometer that was used to test hearing and identify those who could be in an early stage of hearing loss. He even supervised the education of Helen Keller, a deaf and blind student, with whom he remained friends for the duration of his life.[17]

However, Bell also held controversial opinions on deaf intermarriage, influenced by his beliefs in eugenics. Although his work was focused on teaching the deaf to communicate in a way that would allow them to be incorporated back into society, he was nonetheless concerned about the possibility of a “deaf sub-species of humanity.”[18] He submitted a paper to the National Academy of Sciences in 1883, detailing his worries and suggesting restrictive actions. These included discouraging marriages between individuals born deaf and gradually eliminating the use of sign language in favor of spoken language in deaf education. While Bell’s focus on oral communication has been praised for enabling better interaction between the deaf and those who can hear, the foundational beliefs of his work have been criticized for marginalizing the deaf community. His views led to the sidelining of sign language and contributed to the notion that deaf individuals are inherently “flawed,” eroding their self-respect and ability for self-expression.[19]

It was his work on devices used to help the deaf learn to speak that led to his breakthrough with the telephone:

That a pioneer teacher of the deaf – where lack of speeches the human tragedy he grapples with – became the inventor of a device which is based totally on human speech is remarkable enough. But the fact is that deafness played an overwhelming part in the events of his life.[20]

Bell himself said that, “It is only right that it should be known that the telephone is one of the products of the work of the Horace Mann School for the Deaf in Boston and resulted from my attempts to benefit the children of the school..”[21]

The Breakthrough

Bell was searching for a way to graphically record sound waves. He wrote, “If I could make a current of electricity vary in intensity precisely as the air varies in intensity during the production of sound, I should be able to transmit speech telegraphically.”[22] In order to do this, Bell and Watson developed a system in which a diaphragm was suspended in a diluted sulfuric acid which would rise and fall in the acid. A battery current then vibrated a receiver at the other end, producing sound. Although sulfuric acid is no longer used, modern phones still rely on the concept of variable resistance![23]

The breakthrough on March 10th in his Boston attic occurred when Bell spilled sulfuric acid on himself as he was about to test the device with Watson, and he called out, “Mr. Watson, come here, I want you!” Watson heard him through the device for the first time, and rushed back to help, noting he had heard every world clearly.[24][25]This first message every transmitted via Bell’s telephone is noteworthy for several reasons:

…the strict, Victorian formality of Bell’s “Mr. Watson” after months of fraternal associations; Bell’s instinctive use of the primitive telephone to summon aid in what must have been a somewhat disconcerting accident; and the first practical use of this now-everyday instrument as an emergency call for help. No high-sounding phrases before distinguished audiences as the “What hath God wrought?” of Morse’s telegraph. Bell avoided historically self conscious rhetoric used by heads of states. Instead, a simple plea from a human being in trouble attended the telephone’s entrance as a social force. No more appropriate and symbolic event could be imagined or invented.[26]

You can hear Watson describing this breakthrough in the soundtrack for a 1914 film about the invention of the telephone:

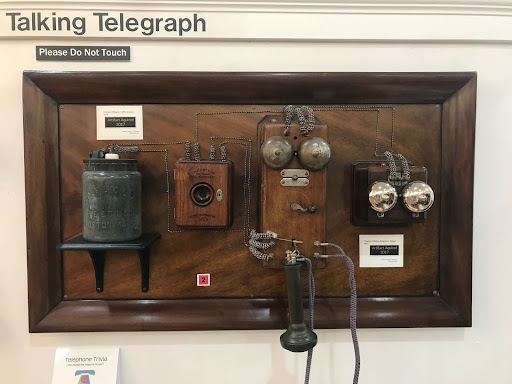

After several more months of enhancements, the telephone, originally perceived as an upgraded “talking telegraph”, was introduced to the public. Another, more recent breakthrough has allowed us to listen to Bell’s voice for the first time, through the recovery of a wax recording:

Bell’s impact is dual-faceted: he transformed global communication through the telephone and had a lasting, albeit disputed, influence on deaf education. These two areas were closely connected, as his work in one often shaped his innovations and thoughts in the other. While his technological contributions are universally praised, his effect on the deaf community continues to be a topic of ongoing discussion and controversy.

For a brief period of time, the telegraph and telephone co-existed, and improvements continued to be made to telegraphic devices. One example includes Edison’s 1877 recording telegraph, which would lead to further work related to recording sound, covered in a future chapter.

Key Takeaways

- The telegraph revolutionized communication, laying the groundwork for modern technologies, and played a pivotal role in the Union’s victory during the Civil War.

- Despite its transformative impact, the telegraph faced numerous challenges, including legislative hurdles and technical setbacks, before becoming a commercial and global success.

- The development of the telegraph and telephone was deeply intertwined with social issues, including the treatment and perception of the deaf community, showcasing the complex relationship between technology and society.

Exercises

- Several inventors like Harrison Gray Dyar and David Alter were mentioned as early experimenters who failed to commercialize their inventions. What factors do you think contributed to their lack of success compared to Samuel Morse and Alexander Graham Bell?

- Alexander Graham Bell had controversial views on deaf education and eugenics. How do you think these views influenced his work, and what ethical considerations arise from this?

- Create a timeline that highlights the key milestones in the development of telecommunication technologies from the early 19th century to the late 19th century. Include inventors, inventions, and significant events like patents and public demonstrations.

Media Attributions

- Samuel Morse © U.S. National Archives is licensed under a Public Domain license

- Wires in Pratt, Kansas-1909 © Image by J.J. Sylvia IV, taken at the New Hampshire Telephone Museum is licensed under a CC BY-NC-SA (Attribution NonCommercial ShareAlike) license

- Pony Express © U.S. National Archives is licensed under a Public Domain license

- Messengers © U.S. National Archives is licensed under a Public Domain license

- Kleinschmidt Perforator © Image by J.J. Sylvia IV is licensed under a CC BY-NC-SA (Attribution NonCommercial ShareAlike) license

- Kleinschmidt Perforator closeup © Image by J.J. Sylvia IV is licensed under a CC BY-NC-SA (Attribution NonCommercial ShareAlike) license

- Printing telegraph © mage by J.J. Sylvia IV is licensed under a CC BY-NC-SA (Attribution NonCommercial ShareAlike) license

- Telegram © U.S. National Archives is licensed under a Public Domain license

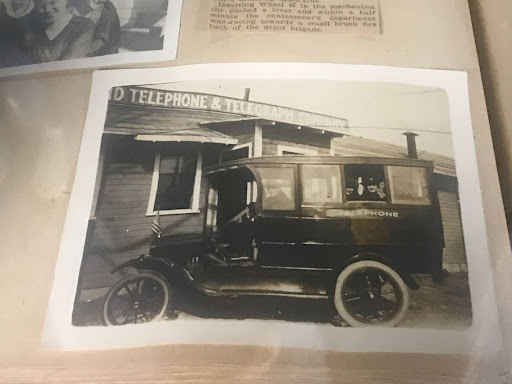

- Car labeled Telephone © Image by J.J. Sylvia IV is licensed under a CC BY-NC-SA (Attribution NonCommercial ShareAlike) license

- Telegraph and telephone equipment © Image by J.J. Sylvia IV is licensed under a CC BY-NC-SA (Attribution NonCommercial ShareAlike) license

- Army Security Agency equipment © Image by J.J. Sylvia IV is licensed under a CC BY-NC-SA (Attribution NonCommercial ShareAlike) license

- Telegraph sending key & receiver © Image by J.J. Sylvia IV is licensed under a CC BY-NC-SA (Attribution NonCommercial ShareAlike) license

- Reis telephone © Wikipedia is licensed under a Public Domain license

- Talking telegraphs © Image by J.J. Sylvia IV is licensed under a CC BY-NC-SA (Attribution NonCommercial ShareAlike) license

- Edison’s recording telegraph © Image by J.J. Sylvia IV is licensed under a CC BY-NC-SA (Attribution NonCommercial ShareAlike) license

- Standage, Tom. The Victorian Internet: The Remarkable Story of the Telegraph and the Nineteenth Century’s on-Line Pioneers. New York London Oxford New Delhi Sydney: Bloomsbury, 2014. ↵

- Standage, Tom. The Victorian Internet: The Remarkable Story of the Telegraph and the Nineteenth Century’s on-Line Pioneers. New York London Oxford New Delhi Sydney: Bloomsbury, 2014. ↵

- Wheeler, Tom. Mr. Lincoln’s T-Mails: The Untold Story of How Abraham Lincoln Used the Telegraph to Win the Civil War. New York: HarperCollins e-books, 2009. ↵

- ibid, p. 20 ↵

- ibid, p. 181 ↵

- Object label for The Army Security Agency at the Fort Devens Museum in Devens, MA.. Seen on: September 5, 2023. ↵

- https://web.archive.org/web/20100706204628/http://www.aei.it/ita/museo/mam_coll.htm ↵

- “Bell ‘Did Not Invent Telephone.’” December 1, 2003. http://news.bbc.co.uk/2/hi/science/nature/3253174.stm. ↵

- New Hampshire Telephone Museum, NHTM (Version 2.2), [Mobile App]. App Store. https://apps.apple.com/us/app/nhtm/id1076102853. ↵

- ibid. ↵

- Standage, Tom. The Victorian Internet: The Remarkable Story of the Telegraph and the Nineteenth Century’s on-Line Pioneers. New York London Oxford New Delhi Sydney: Bloomsbury, 2014. ↵

- Hayes, Derek. Canada: An Illustrated History. Vancouver / Toronto: Douglas & McIntyre, 2004. ↵

- Standage, Tom. The Victorian Internet: The Remarkable Story of the Telegraph and the Nineteenth Century’s on-Line Pioneers. New York London Oxford New Delhi Sydney: Bloomsbury, 2014 ↵

- Boettinger, H. M. The Telephone Book: Bell, Watson, Vail and American Life, 1876-1976. Croton-on-Hudson, N.Y: Riverwood Publishers, 1977. ↵

- Berke, Jamie. “Alexander Graham Bell and His Controversial Views on Deafness.” Verywell Health, July 13, 2023. https://www.verywellhealth.com/alexander-graham-bell-deafness-1046539. ↵

- Martin, Chris. “Alexander Graham Bell and the 1900 Census.” United States Census Bureau, n.d. https://www.census.gov/history/pdf/agbellarticle-32017.pdf ↵

- Boettinger, H. M. The Telephone Book: Bell, Watson, Vail and American Life, 1876-1976. Croton-on-Hudson, N.Y: Riverwood Publishers, 1977. ↵

- ibid ↵

- Berke, Jamie. “Alexander Graham Bell and His Controversial Views on Deafness.” Verywell Health, July 13, 2023. https://www.verywellhealth.com/alexander-graham-bell-deafness-1046539. ↵

- Boettinger, H. M. The Telephone Book: Bell, Watson, Vail and American Life, 1876-1976. Croton-on-Hudson, N.Y: Riverwood Publishers, 1977. ↵

- ibid, p. 153 ↵

- New Hampshire Telephone Museum, NHTM (Version 2.2), [Mobile App]. App Store. https://apps.apple.com/us/app/nhtm/id1076102853. ↵

- Boettinger, H. M. The Telephone Book: Bell, Watson, Vail and American Life, 1876-1976. Croton-on-Hudson, N.Y: Riverwood Publishers, 1977. ↵

- ibid. ↵

- New Hampshire Telephone Museum, NHTM (Version 2.2), [Mobile App]. App Store. https://apps.apple.com/us/app/nhtm/id1076102853. ↵

- Boettinger, H. M. The Telephone Book: Bell, Watson, Vail and American Life, 1876-1976. Croton-on-Hudson, N.Y: Riverwood Publishers, 1977. ↵