8.3 From Dots and Dashes to Dial Tones

Learning Objectives

- Explain the historical development of the telephone, including its rapid adoption and the decline of the telegraph industry.

- Understand the legal and ethical challenges faced by early telephone companies, including patent disputes and discriminatory labor practices.

- Analyze the social and cultural impact of the telephone, including its role in changing communication habits, disrupting social norms, and influencing design and technology.

The telephone was an immediate sensation. From a modest 230 telephones in use by the end of June 1877, the number rapidly escalated to 750 the subsequent month, and to 1,300 a month later. By 1880, there were 30,000 telephones in use globally. This transition towards electric technology signaled the gradual decline of the telegraph industry and its associated traditions and subculture. By 1886, a decade after its invention, there were 250,000 telephones in use. This figure dramatically rose to nearly 2 million by 1900, with a telephone in one out of every ten homes in the U.S. The emergence of the telephone thus marked a significant progression from the telegraph, fundamentally revolutionizing the way people communicated.

The Bell Telephone Company to AT&T

After successfully building his first telephone, Alexander Graham Bell first attempted to sell his patents to the Western Union Telegraph Company, which had emerged as the dominant force in the age of the telegraph. However, Western Union refused to purchase the patents for $100,000 because they believed the telephone was too impractical.[1]

Without a buyer, Bell instead founded his own company, the Bell Telephone Company in 1877, whose first office was located in New Haven, CT. Because he wanted to spend his time continuing his work teaching the deaf community, Bell hired Theodore Vail in 1878 to run the company and begin building its network. Vail had previously worked for the U.S. postal service, overseeing its nationwide delivery. Vail oversaw major projects during his tenure at the company, which helped create the foundation for its future monopoly in the telephone industry. These improvements include the founding of a Western Electric Company division of the company which built and sold telephone related equipment, and the creation of a connection between Boston, MA and Providence, RI, which was the first ever long-distance telephone system.[2]

The development of the telephone system in the U.S. was different from that of most other countries. For example, in England, the telegraph was a nationalized service that was monopolized by the Crown in the form of Queen Victoria. This monopoly extended to the telephone, which was known as the voice telegraph in England. This lack of centralized control in the U.S. led to fierce competition and a series of lawsuits that played a major role in the creation of the nation’s network.[3]

One major lawsuit involved Western Union, which had rather quickly realized it made a mistake in passing on Bell’s patents. They hired Thomas Edison to help establish their own service by making incremental improvements for the telephone, much as he had done for the telegraph.[4] In 1878, the Bell Telephone Company, which was then a tiny, newly formed company, sued Western Union for infringing Bell’s patents. In all, there were over 600 legal actions related to the early inventions of the telephone industry, with five cases going all the way to the Supreme Court. Bell ultimately won every case, but this experience caused him to develop a life-long distaste for the need to commercially develop his inventions.[5] Ultimately, Western Union agreed to leave the telephone market in exchange for 20% of Bell rentals for the remainder of the 17 years of Bell’s patents.[6]

Vail’s leadership was visionary, and he worked insistently to help extend the telephone network nationwide. This process including forming the New England Telephone Company and the National Bell Telephone Company to license the technology to local service companies throughout the country, often named “Bell Telephone Company of…” the local town. By 1885, it was clear that a new company needed to be established in order to oversee all of the overlapping systems involved in the development of the telephone system.[7] Vail founded the American Telephone and Telegraph (AT&T) in New York, with the following charter:

…the lines of this association… will connect one or more points in each and every city, town or place, in the State of New York with one or more points in each and every other city, town or place in said State, and in the rest of the United States, Canada and Mexico, and also by cable and other appropriate means with the rest of the known world as may hereafter become necessary or desirable in conducting the business of the association.[8]

Because of differences in taxes and other corporate capital laws, New York provided a much more suitable home to the now very large telephone company. In 1899, AT&T merged with the Bell American Telephone Company of Boston, with AT&T becoming the parent company to take advantage of the less restrictive New York laws. The company had grown so large, they were able to acquire Western Union.[9]

To avoid antitrust action, AT&T entered into the Kingsbury Commitment in 1913, agreeing to divest its Western Union stock and allow competitors to interconnect with its network. However, AT&T’s Bell System became a nationwide monopoly by 1940, controlling not just long-distance and local service, but also the telephones themselves. This vertical monopoly led to antitrust lawsuits, resulting in a 1956 consent decree that limited AT&T’s market share and opened its patents royalty-free, fostering innovation in the electronics and computer sectors.

Internationally, AT&T had a significant presence, including operations in Canada and the Caribbean, and a 54% stake in Japan’s NEC. However, the 1984 Bell System divestiture, prompted by another antitrust lawsuit, broke up the monopoly into Regional Bell Operating Companies (RBOCs), commonly known as “Baby Bells.”

Post-1984, the telecommunications landscape underwent numerous mergers and acquisitions, transforming the original Baby Bells into major corporations like AT&T Inc., Verizon, and Lumen Technologies. The Bell name and logo have largely disappeared from the U.S. market but continue to be used in Canada by Bell Canada.

Today, AT&T and its offshoots are part of a much more competitive and diversified telecommunications industry, but the company’s legacy as a pioneering and at times monopolistic force continues to be felt.

Telephone Design

Telephone technology continued to develop quickly. One very early model, circa 1878, was the Doolittle telephone. This design quickly gave way to what became known as coffin phones, so called because the wooden box that contains the inner working is shaped somewhat like a coffin. They were designed to be mounted on the wall and were among some of the very first phones to be installed in homes and businesses. Most coffin phones had a magneto system, which the user would crank to generate a signal that rang the operator or the other party’s phone. They had a separate earpiece and mouthpiece, akin to the candlestick models that came later. Because early phone lines didn’t deliver electrical power, these telephones often contained wet-cell batteries to provide the necessary electrical charge for operation. The coffin phone’s old-fashioned aesthetic has made it a popular element in various subcultures that romanticize past technologies, such as Steampunk.

The Impact of Disease

By the end of the 1880s, telephone housings were made of walnut and cherry wood, the bells of brass or nickel, and the mouthpieces of brass or vulcanite. However, in the 1918 flu and the rise of tuberculosis created concern about the role telephones might play in the spread of these diseases. To help combat these concerns, the mouthpieces incorporated glass and porcelain, which could be unscrewed and boiled in order to clean them.[10] Some even marketed personal mouthpieces for phones that one could carry with them and attach to any phone they use.[11]

The fear of labor shortages related to measles also played an instrumental role in the development and adoption of telephone numbers. The use of such numbers was initially very unpopular because customers saw them as a dehumanizing loss of personal identity. But ultimately, numbers were much easier to use than names for operators who hadn’t memorized which ports on a switchboard were associated with which customer:

In 1880 at Lowell, Massachusetts, a respected physician, Dr. Parker, during an epidemic of the measles, recommended the use of numbers because he feared paralysis of the town’s telephone system if the four operators succumbed. He felt that substitute operators could be trained more easily if an emergency disabled experienced personnel. When introduced, the practicality of the arrangement was quickly perceived and became general. In 1895, official instructions to operators specified, “Number, please?” as the proper response to a customer.[12]

The COVID-19 pandemic also introduced significant changes to the telecommunications industry. In 2020, many employees transitioned to working from home and using a variety of video conferencing software such as Google Meet and Zoom. The use of such technology has led to a conflict over work-from-home policies as many corporations asked for employees to return to the office in subsequent years.

Continued Design Innovation

The “Candlestick Phone,” also known as the “Upright Desk Stand” or simply the “Stick Phone,” is an iconic telephone design that defined an era in telecommunications. Its unique shape, resembling a candlestick, made it instantly recognizable and represented a significant leap forward in both design and function. The candlestick phone gained prominence in the late 1890s and remained popular through the 1920s. It replaced earlier designs, such as the wooden coffin phones, becoming the standard design in many households and businesses. It also moved phones off of walls and onto desks, allowing for longer conversations while seated.

One of the most distinguishing features of the candlestick phone was its separation of the transmitter (mouthpiece) and the receiver (earpiece). The transmitter was mounted on a long, vertical shaft, while the receiver was a separate piece attached by a cord and lifted to the ear during use. Initially, candlestick phones were commonly used with a separate bell box and were operator-assisted. However, with the introduction of the rotary dial, the design was adapted to include this feature, enabling direct dialing. The development of handsets that combined both the transmitter and receiver into a single unit led to the decline of the candlestick phone. The iconic design has left a lasting impression. It often appears in period pieces and films to signify the era. Even modern reproductions are available for those who want a retro flair to their décor.

Moving into the 1950’s telephone design exploded into a wide variety of designs, colors, and styles. Notably, some designs began to move back to the wall, and began to feature longer cords that allowed for movement. The headset and dial became combined into a single piece, anticipating future cordless phones. Marketing for the phones became more targeted, with for example, the launch of Bell’s Princess Telephone with the slogan, “It’s little! It’s lovely! It lights!” It wasn’t until the 1980’s however, that the Bell System allowed customers to use phones purchased from another company.[13]

Learn more about the history of the cell phone from this NPR story:.

Phone Switches

On January 28, 1878, the Boardman Building in New Haven became a landmark in telecommunications history as it hosted the world’s inaugural commercial telephone exchange, conceived by Civil War veteran George Coy along with Herrick Frost and Walter Lewis. The initiative was particularly groundbreaking because, until then, telephones were individually owned or leased in pairs, typically connecting a home to a business. This setup required people to also hire telegraph contractors to lay the connecting wires. Coy revolutionized this by developing a primitive switchboard made of spare parts like carriage bolts and teapot handles. This allowed a central office to link multiple users, enabling subscribers to only need one telephone to connect with an unlimited number of other users. For a monthly fee of $1.50, the 21 initial subscribers could make calls via the central office, which employed operators to facilitate the connections. Notably, direct dialing didn’t become standard until the 1920s. Just a few weeks later, on February 21, 1878, another milestone was achieved when Coy’s company released the world’s first telephone directory. It was a single-page flier listing 50 individuals and businesses in New Haven, including Coy, Frost, and Lewis as residential subscribers.[14]

Discriminatory Labor Practices

The New Hampshire Telephone Museum explores the problematic discriminatory labor practices of early exchanges. In the early days of telephone companies, teenage boys were initially employed as operators, largely because they were already accustomed to working in telegraph offices and accepted lower wages. However, the job of a telephone operator demanded a level of patience and decorum that these young boys lacked. Their rowdy behavior, which included pranks and even cursing at callers, made them unsuitable for the role. Recognizing this, the Boston Telephone Dispatch Company began hiring female operators in 1878. Women were perceived to have more pleasant voices and better manners, making them more appealing to the predominantly male customer base. Additionally, because gender inequality was rampant at the time, female operators could be paid less and managed more strictly than their male counterparts. Employment options for women wanting to work outside the home were limited to roles like servant, factory worker, sales clerk, nurse, or teacher. To become a telephone operator, women typically had to be unmarried, between the ages of 17 and 26, and have arms long enough to reach the top of the tall switchboards. Discriminatory practices also barred African American and Jewish women from these roles. Operators earned a meager seven dollars per week and worked long, inflexible hours, often including nights and holidays.[15]

The role of the telephone operator evolved into a critical component of the communication infrastructure. While managing the switchboard, operators were expected to provide additional services, such as disseminating election results, train arrivals, and weather updates. However, the working conditions varied significantly between rural and urban settings. In rural areas, operators could attach long cords to their headsets, allowing them to complete household chores while waiting for calls, thereby enjoying a certain degree of independence. Conversely, city operators faced a high-paced environment, handling up to 600 calls an hour. Efficiency was paramount, leading telephone companies to enlist scientific management teams that established stringent rules governing everything from posture to the time taken to answer calls. Supervisors closely monitored operators, even eavesdropping on conversations. Strict rules were enforced to the point where operators had to ask for permission for even basic needs like going to the bathroom, and infractions could result in humiliating punishments, such as being sent to a “punishment room” for tardiness.[16]

Pop Culture Influence

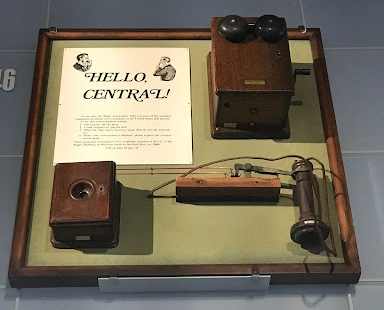

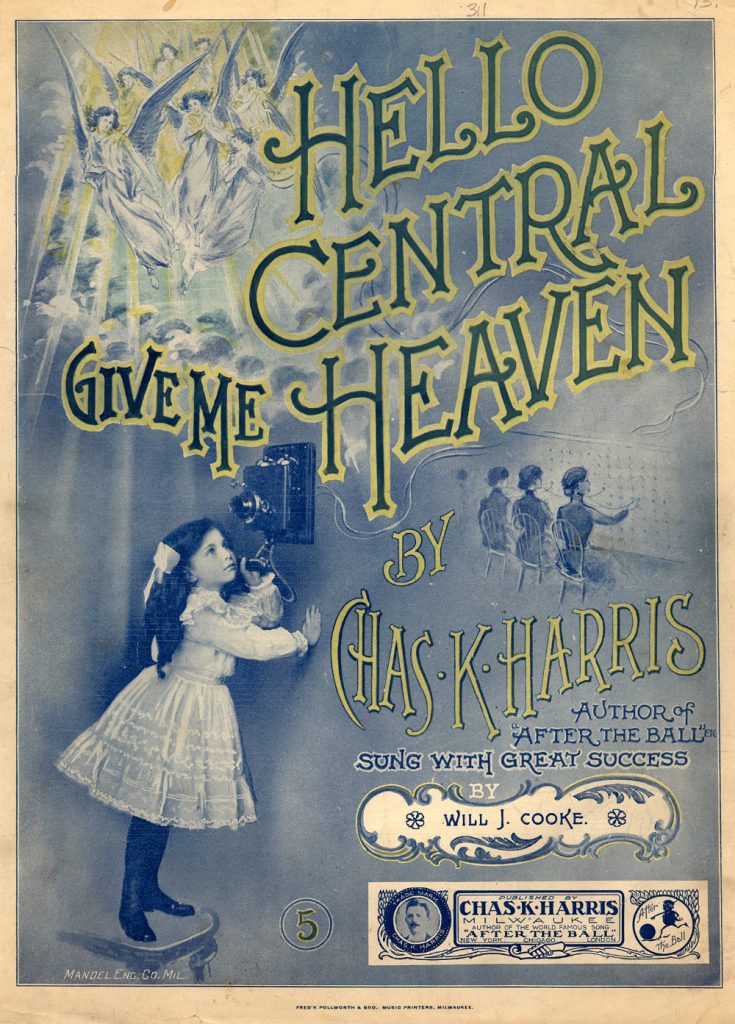

Because the phone switches were manual, users would need to call into a central station and ask for assistance. The phrase, “Hello, Central” was popularized as a way to greet the operator who answered your call.

The phrase was popularized in the 1901 song, “Hello, Central, Give Me Heaven,” which tells the story of a young child asking a telephone operator to connect her to her deceased mother, in Heaven.

Automatic Switching

Although it would be many years before the phone industry transitioned from manual to automatic switching, the roots for this technological innovation began in 1888 with an undertaker:

Mr. Strowger was the only undertaker in Kansas City. He heard another one was going to be moving into town, but didn’t worry about losing any business because he was very well-established and everyone knew him. One day, however, Mr. Strowger was sipping his coffee and reading his morning newspaper – in particular the obituaries – and noticed the new undertaker was listed as performing many of the funeral services. Mr. Strowger did a little investigative work and learned that the new undertaker was actually married to the local telephone operator. Since she was handling all of the calls in town, she was directing everyone who was looking for an undertaker to her husband, rather than Mr. Strowger. Convinced that it should be subscribers, rather than the operator, who chose who was called, he first conceived his invention in 1888, and patented the automatic telephone exchange in 1891.[17]

Despite this invention, manual switchboards continued in operation well into the 20th century. To meet the increased telephone demands of the U.S. military during World War I, Bell System purchased the patent for the automatic switch from Strowger for 2.5 million dollars. The technology was slowly rolled out exchanges across the country, but it was met with some hesitation by consumers. AT&T produced educational videos that helped teach people how to dial for themselves! By the 1950s, the volume of traffic had increased so much that it became unrealistic for this switching to continue manually. By the 1960s, almost all exchanges in the U.S. had been converted to automatic switching. Initially analog in nature, these were later converted to digital.[18]

Fear of Dehumanization

As we’ve seen, all new technological inventions tend to provoke both fear and excitement. One common fear is that of dehumanization, the fear that the technology will somehow erode what it means to be “truly” human. Of course, as we read earlier theories of technogenesis suggest that humans have always evolved with the technology that they use and create. Nonetheless, these fears remain constant. The Anti-Digit Dialing League, a group that arose to protest dialing phone numbers, offers a classic example of this fear.

The Anti-Digit Dialing League existed for only two years in the 1960s and attempted to fight against the “creeping numeralism of phone dialing, explaining in an article in Time magazine[19]:

These people are systematically trying to destroy the use of memory. They tell you to ‘write it down,’ not memorize it. Try writing a telephone number down in a dark booth while groping for a pencil, searching in an obsolete phone book and gasping for breath. And all this in the name of efficiency! Engineers have a terrible intellectual weakness. ‘If it fits the machine,’ they say, ‘then it ought to fit people.’ This is something that bothers me very much: absentmindedness about people.[20]

Perhaps even more extreme, the group used sabotage methods to try demonstrate the ridiculousness of using a numeric system:

Interpreting the area code and seven digits as one huge number, they place calls by saying, “Operator, give me S.I. Hayakawa at four billion, one hundred fifty-five million, eight hundred forty-two thousand, three hundred and one.” Growls Chapter Leader Frederick Litto, “If they want digits, we’ll give them digits.”[21]

In addition to citing psychological studies that claimed strings of numbers were difficult to memorize, the group used a question-and-answer format to explain their cause[22]:

Q. But isn’t all this fuss simply a tempest in a teapot? Aren’t the people opposing Digit Dialing really just opposing progress? Isn’t the present furor nothing more than an emotional reaction to any kind of change?

A. Most decidedly not! Most people, and certainly the members of ADDL, welcome constructive change. However, the telephone is an extremely important part of everyday life, and major changes in its use will have widespread effects.[23]

These arguments about memory and widespread change have been made over and over again throughout history, dating back to Socrates complaining that the invention of alphabetic hand-writing would ruin one’s memory.

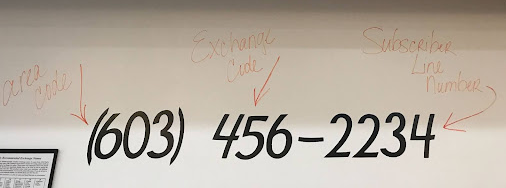

Long Distance Area Codes

Area codes were developed as part of the North American Numbering Plan (NANP) to organize and facilitate the rapidly expanding telephone network. Introduced in 1947, this system was designed to simplify direct-dial long-distance calling and automate the connection process, which was previously managed manually by operators. Each area code was assigned to a specific geographic region and served as the first part of a standard 10-digit phone number in the United States, Canada, and other participating countries. The area code helped to route the call to the appropriate local exchange within that region. Initially, the codes were distributed based on population density; areas with higher populations received codes that were quicker to dial on rotary phones. As technology evolved and the demand for phone lines grew, new area codes were added, and existing ones were split or overlaid to accommodate more numbers. This system has continued to adapt, but the basic concept of area codes as geographic identifiers in the numbering plan remains in place. You can view area codes by state here: NANPA Area Codes Map

Social Upheaval

Carolyn Marvin explored the social upheaval that stemmed from the telephone extensively in her 1988 book, When Old Technologies Were New: Thinking About Electric Communication in the Late Nineteenth Century.[24] She argues that, in its early years, the telephone was entangled in two contrasting and deeply emotional narratives. On one hand, some viewed this newfound technology as a chaotic, disorganizing force capable of eroding established social mores and structures. On the other, it was seen as a revolutionary tool that could bring people together, creating an interconnected web of community unlike anything seen before.

When the telephone first arrived, electrical engineers and experts sounded the alarms, cautioning society about the untold impact it might have. These individuals were not just concerned about the mechanics of this new invention; they were fearful of its potential to fundamentally alter familiar forms of social knowledge, interaction, and even authority. It was as though the telephone threatened to democratize information and power in a way that would make traditional forms of social control less effective.

This concern was not limited to unknown citizens but extended to public figures who found themselves accessible in previously unthinkable ways. Take, for instance, Chauncey Depew, the governor of New York at the time. Depew was bombarded by what the media termed “telephone maniacs”—people who would call him every time a news story or comment about him was published. This sort of instant accessibility blurred the boundaries between the public and private spheres, causing anxiety among those accustomed to a more clearly defined social hierarchy.

Equally worrisome for many was the telephone’s perceived capacity to invade the privacy of the domestic sphere. Families, long considered a sanctuary from the public eye, were now vulnerable to external scrutiny. The telephone emerged as a double-edged sword: while offering the convenience of easy communication, it also raised uncomfortable ethical questions about the sanctity of family life and intimacy. In 1877, the New York Times went as far as to brand the telephone’s nature as “atrocious,” largely due to its potential to reveal family secrets and turn the private public.

One societal segment that felt the heat of this technological revolution was the bourgeois family. The telephone seemed to collapse traditional barriers that safeguarded the family unit, leading to unintended social mingling and making it challenging to maintain essential markers of social distance like class and race. With the erosion of these barriers, society started to panic about how to enforce the age-old distinctions that had been relatively straightforward to maintain before this technological upheaval.

It wasn’t just social classes that were disrupted; gender roles were also questioned. The early telephone era gave birth to the “telephone girl”—the female operator tasked with connecting calls. This new role gave women a novel form of agency and public presence, but it was fraught with societal apprehensions. The community feared that these young women would be exposed to the advances of men from different social strata, undermining the traditional social norms of courtship and marriage.

Interestingly, the telephone was also seen as a tool for control, especially in the domestic environment of the upper classes. In such households, the device became a conduit through which orders could be more efficiently given to servants. It offered a semblance of an ideal domestic scenario, where control of the household remained firmly entrenched with the masters and parents.

However, the telephone also posed challenges to the very notion of privacy within the home. While it offered a constant connection to the outside world, it came at the cost of sudden, and often intrusive, interruptions. This dilemma highlighted society’s ambivalence towards new technology. Other innovations, like the phonograph, didn’t incur the same level of social concern because they were less invasive and more controllable, indicating a complex emotional relationship with different forms of new technology.

In a broader political and social context, the telephone revealed an undercurrent of tension between democratic ideals and actual power dynamics. Initially touted as a force for democratization, the technology also exposed underlying societal efforts to maintain existing hierarchies. Thus, the telephone became a subject of paradoxical public discourse—it was extolled for its potential to democratize communication while being subtly branded as a tool that would never truly serve the broader population.

In summary, the early history of the telephone is a fascinating study of social and ethical challenges that extended far beyond the technical realm. The telephone didn’t just alter how we communicated; it touched the very core of societal values, norms, and structures. It elicited both fear and excitement as people grappled with its potential to unravel established norms and offer new methods of control and connectivity. As we look back, it’s clear that many of the questions and dilemmas that surrounded the telephone’s early years continue to resonate in our current age of digital interconnectivity.

The End of an Era

Western Union discontinued its telegram services on January 27, 2006, marking the end of the telegraph era in North America. Some services continued in other parts of the world until 2013, but the telegraph had largely been replaced by newer forms of communication.

Key Takeaways

- The telephone revolutionized communication, rapidly gaining popularity and leading to the decline of the telegraph industry, while also facing numerous legal challenges including patent disputes.

- The development and adoption of the telephone had significant social and cultural impacts, including changes in labor practices, gender roles, and societal norms around privacy and communication.

- The telephone’s history is marked by both technological innovation and social upheaval, raising ethical and societal questions that continue to be relevant in the age of digital interconnectivity.

Exercises

- How did the telephone disrupt existing social norms and labor practices, especially in terms of gender roles and privacy? Discuss the positive and negative impacts of this disruption.

- Research a major lawsuit or patent dispute in the early history of the telephone. Summarize the key points of the case and its outcome, and explain how it shaped the development of the telecommunications industry.

- The telephone underwent various design changes over the years, from the Doolittle telephone to the candlestick phone and beyond. How do these design changes reflect broader societal and technological shifts?

Media Attributions

- Doolittle Telephone © Image by J.J. Sylvia IV is licensed under a CC BY-NC-SA (Attribution NonCommercial ShareAlike) license

- Coffin phone designs © Image by J.J. Sylvia IV is licensed under a CC BY-NC-SA (Attribution NonCommercial ShareAlike) license

- Candlestick telephone © Image by J.J. Sylvia IV is licensed under a CC BY-NC-SA (Attribution NonCommercial ShareAlike) license

- Variety of telephone designs © Image by J.J. Sylvia IV is licensed under a CC BY-NC-SA (Attribution NonCommercial ShareAlike) license

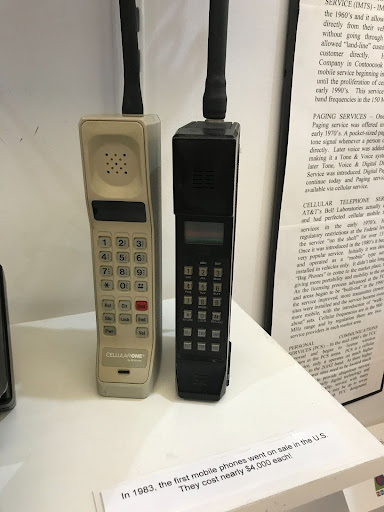

- First mobile phones © Image by J.J. Sylvia IV is licensed under a CC BY-NC-SA (Attribution NonCommercial ShareAlike) license

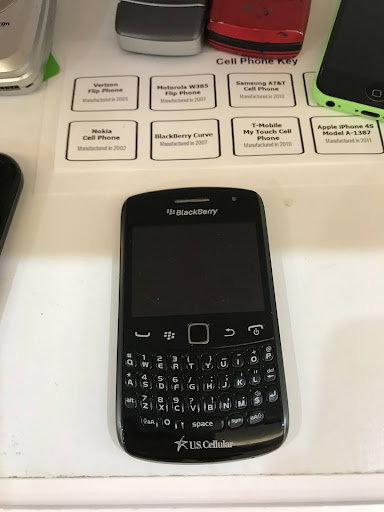

- Blackberry Curve © Image by J.J. Sylvia IV is licensed under a CC BY-NC-SA (Attribution NonCommercial ShareAlike) license

- Women phone operators © Image captured by J.J. Sylvia IV is licensed under a CC BY-NC-SA (Attribution NonCommercial ShareAlike) license

- Hello, Central! phone display © Image by J.J. Sylvia IV is licensed under a CC BY-NC-SA (Attribution NonCommercial ShareAlike) license

- Hello Central cover © Wikipedia is licensed under a Public Domain license

- Bryant Pond Telephone © Image by J.J. Sylvia IV is licensed under a CC BY-NC-SA (Attribution NonCommercial ShareAlike) license

- Phone number © Image by J.J. Sylvia IV is licensed under a CC BY-NC-SA (Attribution NonCommercial ShareAlike) license

- New Hampshire Telephone Museum, NHTM (Version 2.2), [Mobile App]. App Store. https://apps.apple.com/us/app/nhtm/id1076102853. ↵

- ibid ↵

- Boettinger, H. M. The Telephone Book: Bell, Watson, Vail and American Life, 1876-1976. Croton-on-Hudson, N.Y: Riverwood Publishers, 1977. ↵

- New Hampshire Telephone Museum, NHTM (Version 2.2), [Mobile App]. App Store. https://apps.apple.com/us/app/nhtm/id1076102853. ↵

- Boettinger, H. M. The Telephone Book: Bell, Watson, Vail and American Life, 1876-1976. Croton-on-Hudson, N.Y: Riverwood Publishers, 1977. ↵

- New Hampshire Telephone Museum, NHTM (Version 2.2), [Mobile App]. App Store. https://apps.apple.com/us/app/nhtm/id1076102853. ↵

- Boettinger, H. M. The Telephone Book: Bell, Watson, Vail and American Life, 1876-1976. Croton-on-Hudson, N.Y: Riverwood Publishers, 1977. ↵

- ibid. p. 102 ↵

- ibid. ↵

- New Hampshire Telephone Museum, NHTM (Version 2.2), [Mobile App]. App Store. https://apps.apple.com/us/app/nhtm/id1076102853. ↵

- Gifford, Clive, ed. Media & Communication. Eyewitness Books 104. London: Dorling Kindersley, 2000. ↵

- Boettinger, H. M. The Telephone Book: Bell, Watson, Vail and American Life, 1876-1976. Croton-on-Hudson, N.Y: Riverwood Publishers, 1977, p. 106 ↵

- New Hampshire Telephone Museum, NHTM (Version 2.2), [Mobile App]. App Store. https://apps.apple.com/us/app/nhtm/id1076102853. ↵

- Smith. “First Commercial Telephone Exchange – Today in History: January 28 - Connecticut History | a CTHumanities Project.” Connecticut History | a CTHumanities Project - Stories about the people, traditions, innovations, and events that make up Connecticut’s rich history., January 28, 2020. https://connecticuthistory.org/the-first-commercial-telephone-exchange-today-in-history/. ↵

- Object label for Telephone Exchange Photos at the New Hampshire Telephone Museum, Warner, NH. Seen on: August 8, 2023. ↵

- ibid ↵

- New Hampshire Telephone Museum, NHTM (Version 2.2), [Mobile App]. App Store. https://apps.apple.com/us/app/nhtm/id1076102853. ↵

- ibid ↵

- Leddy, Michael. “The Anti-Digit Dialing League.” Orange Crate Art (blog), April 12, 2012. https://mleddy.blogspot.com/2012/04/anti-digit-dialing-league.html ↵

- TIME.com. “The TIME Vault: July 13, 1962.” Accessed September 2, 2023. http://time.com/vault/issue/1962-07-13/. ↵

- ibid ↵

- Leddy, Michael. “Phones Are For People.” Orange Crate Art (blog), April 23, 2012. https://mleddy.blogspot.com/2012/04/phones-are-for-people.html. ↵

- Anti Digit Dialing League. Phones Are For People, 1962. (as quoted in Leddy). ↵

- Marvin, Carolyn. When Old Technologies Were New: Thinking about Electric Communication in the Late Nineteenth Century. 1. issued as an Oxford Univ. Press paperback, 9. print. New York, NY: Oxford Univ. Press, 1990. ↵