1.0 What is Anthropology?

Remix Authors:

Vanessa Martínez, Holyoke Community College

Demetrios Brellas, Framingham State University

Original Authors:

Katie Nelson, Inver Hills Community College

Lara Braff, Grossmont College

Learning Objectives

- Identify the four subfields of anthropology and describe the kinds of research projects associated with each subfield.

- Describe how anthropology developed from early explorations of the world through the professionalization of the discipline in the 19th century.

- Discuss ethnocentrism and the role it played in early attempts to understand other cultures.

- Explain how the perspectives of holism, cultural relativism, comparison, and fieldwork, as well as both scientific and humanistic tendencies make anthropology a unique discipline.

- Examine the ways in which anthropology can be used to address current social, political, and economic issues.

1.1 Introduction

Vanessa’s Story

I remember the first anthropology class that I took in my second year of college. It was a cultural anthropology class taught by Dr. Sabine Hyland, an American anthropologist and ethnohistorian working in the Andes. It was challenging and exciting, and she was the first real mentor I ever had. Her research and teaching style allowed me to engage with topics and questions that I loved inside the college classroom. The way she taught brought you into the stories and research of the communities she highlighted, giving a rich understanding of our diverse world. A class really can change the trajectory of your life. This class did. I fell in love with anthropology and wanted to merge it with my interest in health and wellbeing. It was this class, and this professor, that made me see that there were many more options for degrees, and that medical anthropology could be my path. I am someone who wants to leave the world better than I found it. I found that with anthropology, a discipline devoted to better understanding of humanity as a whole, I could investigate questions that I was curious about and develop solutions to real world problems by centering humanity as cooperative and creative. Years later, I even wrote a recommendation letter for Dr. Hyland to receive tenure, which she did. One class and one mentor can make a difference in the trajectory of your life.

Demetri’s Story

I came to the field of anthropology completely by accident. I entered college at Stony Brook University in New York as a biology major and was considering a pre-med pathway. I always had a passion for science but admittedly the push towards medicine was largely because— well, because according to my parents who came from Greece in the late 70s, every “good Greek boy” had to become a doctor or lawyer (even though they both grew up in tiny agricultural villages). When I first met my R.A. during freshman orientation, I mentioned needing an elective course. He suggested taking cultural anthropology as the course would be fun and the professor was “a character”. Admittedly at the time, I had very little idea of what anthropology was, but the course description sounded interesting so I registered for it. This ended up being the very first college course I attended on the first day of my life as a college student. The professor, William Arens, was indeed eccentric. Although his somewhat controversial research on cannibalism (or lack thereof) in human societies has been met with almost universal criticism, he was one of the most vibrant and engaging professors I had as an undergraduate. The topics he discussed and the people he introduced us to were eye-opening. The way he casually discussed taboo topics and his use of narrative in the classroom really brought culture to life. Before I knew it, I was taking more anthropology courses on various topics, including: the anthropology of food, medical anthropology, physical anthropology, and many others. When I took my first Archaeology course, and subsequently my archaeological field school in Pompeii, Italy, I knew I wanted to become an archaeologist. Being able to connect with past cultures through their material remains is the closest human beings can get to a time machine. Once I felt that connection, I was in love. Luckily for me, I was able to combine my training in biology with my interest in archaeology, through the interpretation of animal remains, leading to my doctoral research in zooarchaeology.

If you are reading this textbook for your cultural anthropology course, you are likely wondering, much like we did, what anthropology is all about. Perhaps the course description appealed to you in some way, but you had a hard time articulating what exactly drove you to enroll. With this book, you are in the right place!

Self Reflection: What are you excited to learn about this semester in this class?

1.2 What is Anthropology?

Anthropology is the study of human beings. Anthropologists investigate everything and anything that makes us human– from culture, to language, to material remains and human evolution. Anthropologists examine every dimension of humanity by asking compelling questions like: How did we come to be human and who are our ancestors? Why do people look and act so differently throughout the world? What do we all have in common? How have we changed culturally and biologically over time? What factors influence diverse human beliefs and behaviors throughout the world?

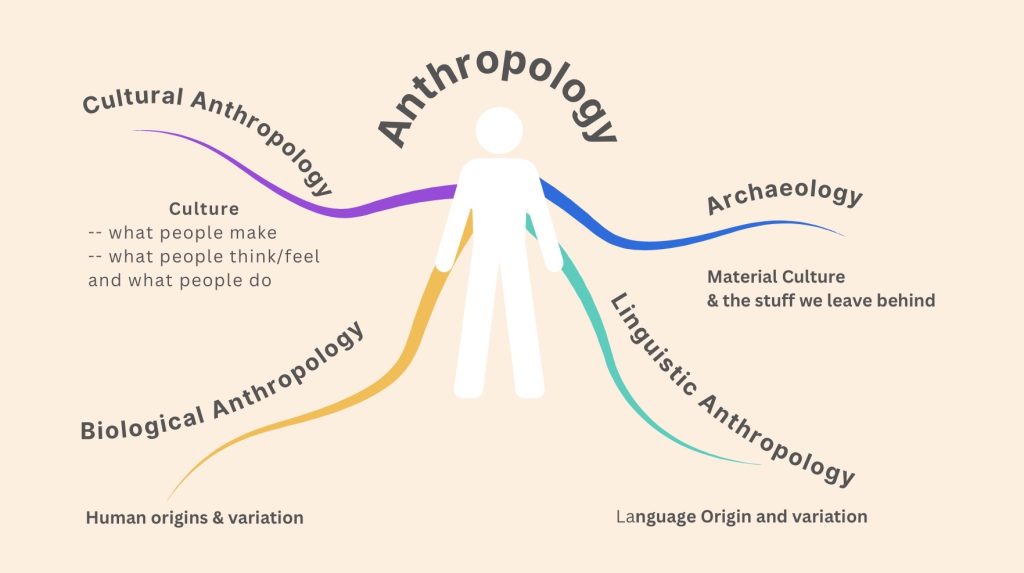

You may notice that these questions are very broad. Indeed, anthropology is an expansive field of study. It comprises four subfields that in the United States include cultural anthropology, archaeology, biological (or physical) anthropology, and linguistic anthropology. Together, the subfields provide a multi-faceted picture of the human condition.

It is important to note that in other parts of the world, anthropology is structured differently. For instance, in the United Kingdom and many European countries, the subfield of cultural anthropology is referred to as social (or socio-cultural) anthropology. Archaeology, biological anthropology, and linguistic anthropology are frequently considered to be part of different disciplines. In some countries, like Mexico, anthropology tends to focus on the cultural and indigenous heritage of groups within the country rather than on comparative research. In Canada, some university anthropology departments mirror the British social anthropology model by combining sociology and anthropology. As noted above, in the United States and most commonly in Canada, anthropology is organized as a four-field discipline. You will read more about the development of this four-field approach in the Doing Fieldwork chapter (chapter three).

Applied anthropology is another area of specialization within or between the anthropological subfields. It aims to solve specific practical problems in collaboration with governmental, non-profit, and community organizations as well as businesses and corporations.

1.3 What is Cultural Anthropology?

The focus of this textbook is cultural anthropology, the largest of the subfields in the United States as measured by the number of people who graduate with PhDs each year.[1] Cultural anthropologists study the similarities and differences among living societies and cultural groups. Through immersive fieldwork, living and working with the people one is studying, cultural anthropologists suspend their own sense of what is “normal” in order to understand other people’s perspectives. Beyond describing another way of life, anthropologists ask broader questions about humankind: Are human emotions universal or culturally specific? Does globalization make us all the same, or do people maintain cultural differences? For cultural anthropologists, no aspect of human life is outside their purview. They study art, religion, healing, natural disasters, and even pet cemeteries. While many anthropologists are at first intrigued by human diversity, they come to realize that people around the world share much in common.

Cultural anthropologists often study social groups that differ from their own, based on the view that fresh insights are generated by an outsider trying to understand the insider point of view. For example, beginning in the 1960s Jean Briggs (1929-2016) immersed herself in the life of Inuit people in the central Canadian arctic territory of Nunavut. She arrived knowing only a few words of their language but ready to brave sub-zero temperatures to learn about this remote, rarely studied group of people. In her most famous book, Never in Anger: Portrait of an Eskimo Family (1970), she argued that anger and strong negative emotions are not expressed among families that live together in small igloos amid harsh environmental conditions for much of the year. In contrast to scholars who see anger as an innate emotion, Briggs’ fieldwork and research shows that all human emotions develop through culturally specific child-rearing practices that foster some emotions and not others.

While cultural anthropologists traditionally conduct fieldwork in faraway places, they are increasingly turning their gaze inward to observe their own societies or subgroups within them. For instance, in the 1980s, American anthropologist Philippe Bourgois sought to understand why pockets of extreme poverty persist amid the wealth and overall high quality of life in the United States. To answer this question, he lived with Puerto Rican crack dealers in East Harlem, New York. He contextualized their experiences both historically in terms of their Puerto Rican roots and migration to the U.S., and in the present as they experienced social marginalization and institutional racism. Rather than blame the crack dealers for their poor choices or blame our society for perpetuating inequality, he argued that both individual choices and social structures can trap people in the overlapping worlds of drugs and poverty (Bourgois 2003).

1.4 Beyond Cultural Anthropology

1.4.1 What is Biological Anthropology?

Biological anthropology is the study of human origins, evolution, and variation. Some biological anthropologists focus on our closest living relatives, monkeys and apes. They examine the biological and behavioral similarities and differences between nonhuman primates and human primates (us!). For example, Jane Goodall has devoted her life to studying wild chimpanzees (Goodall 1996). When she began her research in Tanzania in the 1960s, Goodall challenged widely held assumptions about the inherent differences between humans and apes. At the time, it was assumed that monkeys and apes lacked the social and emotional traits that made human beings such exceptional creatures. However, Goodall discovered that, like humans, chimpanzees also make tools, socialize their young, have intense emotional lives, and form strong maternal-infant bonds. Her work highlights the value of field-based research in natural settings that can help us understand the complex lives of nonhuman primates.

Other biological anthropologists focus on extinct human species, asking questions like: What did our ancestors look like? What did they eat? When did they start to speak? How did they adapt to new environments? In 2013, a team of women scientists excavated a trove of fossilized bones in the Dinaledi Chamber of the Rising Star Cave system in South Africa. The bones turned out to belong to a previously unknown hominin species that was later named Homo naledi. With over 1,550 specimens from at least fifteen individuals, the site is the largest collection of a single hominin species found in Africa (Berger, 2015). Researchers are still working to determine how the bones were left in the deep, hard to access cave and whether or not they were deliberately placed there. Here is a short National Geographic clip that discusses this. They also want to know what Homo naledi ate, if this species made and used tools, and how they are related to other Homo species. Biological anthropologists who study ancient human relatives are called paleoanthropologists. The field of paleoanthropology changes rapidly as fossil discoveries and refined dating techniques offer new clues into our past.

Other biological anthropologists focus on humans in the present including their genetic and phenotypic (observable) variation. For instance, Nina Jablonski has conducted research on human skin tone, asking why dark skin pigmentation is prevalent in places, like Central Africa, where there is high ultraviolet (UV) radiation from sunlight, while light skin pigmentation is prevalent in places, like Nordic countries, where there is low UV radiation. She explains this pattern in terms of the interplay between skin pigmentation, UV radiation, folic acid, and vitamin D. In brief, too much UV radiation can break down folic acid, which is essential to DNA and cell production. Dark skin helps block UV, thereby protecting the body’s folic acid reserves in high-UV contexts. Light skin evolved as humans migrated out of Africa to low-UV con texts, where dark skin would block too much UV radiation, compromising the body’s ability to absorb vitamin D from the sun. Vitamin D is essential to calcium absorption and a healthy skeleton. Jablonski’s research shows that the spectrum of skin pigmentation we see today evolved to balance UV exposure with the body’s need for vitamin D and folic acid (Jablonski 2012). For more information regarding Jablonski’s work please review The Evolution of Skin Color website.

Quick Reading Check: What types of questions are biological anthropologists interested in and why?

1.4.2 What does it mean to be an archaeologist? What is material culture?

Take a look around you, chances are you are surrounded by “stuff”. From the clothing you are wearing to the screen you are staring at and the vessel from which you are drinking, much of our culture plays out in the material world in some form. After all, it is this stuff or what anthropologists call material culture which separates us from other living things on earth. Now picture if all that was left of your existence is the stuff surrounding you. This is the situation that archaeologists often face when trying to examine culture. Archaeologists focus on the material past: the tools, food, pottery, art, shelters, seeds, and other objects left behind by people. Prehistoric archaeologists recover and analyze these materials to reconstruct the lifeways of past societies that lacked writing. They ask specific questions like: How did people in a particular area live? What did they eat? Why did their societies change over time? They also ask general questions about humankind: When and why did humans first develop agriculture? How did cities first develop? How did prehistoric people interact with their neighbors? The method that archaeologists use to answer their questions is excavation—the careful digging and removal of dirt and stones to uncover material remains while recording their context. Archaeological research spans millions of years from human origins to the present. For example, British archaeologist Kathleen Kenyon (1906-1978), was one of few female archaeologists in the 1940s. She famously studied the city structures and cemeteries of Jericho, an ancient city dating back to the Early Bronze Age (3,200 years before the present) located in what is today the West Bank. Based on her findings, she argued that Jericho is the oldest city in the world and has been continuously occupied by different groups for over 10,000 years (Kenyon 1979).

Historical archaeologists study recent societies using material remains to complement the written record. The Garbage Project, which began in the 1970s, is an example of a historic archaeological project based in Tucson, Arizona. It involves excavating a contemporary landfill as if it were a conventional archaeology site. Archaeologists have found discrepancies between what people say they throw out and what is actually in their trash. In fact, many landfills hold large amounts of paper products and construction debris (Rathje and Murphy 1992). This finding has practical implications for creating environmentally sustainable waste disposal practices.

In 1991, while working on an office building in New York City, construction workers came across human skeletons buried just 30 feet below the city streets. Archaeologists were called in to investigate. Upon further excavation, they discovered a six-acre burial ground, containing 15,000 skeletons of free and enslaved Africans who helped build the city during the colonial era. The “African Burial Ground,” which dates from 1630 to 1795, contains a trove of information about how free and enslaved Africans lived and died. The site is now a national monument where people can learn about the history of slavery in the U.S.[2]

Quick Reading Check: What type of research archaeologists do and what aspects of humanity do they study?

1.4.3 What is Linguistic Anthropology?

Language is a defining cultural trait of human beings. While other animals have communication systems, only humans have complex, symbolic languages—over 6,000 of them! Human language makes it possible to teach and learn, to plan and think abstractly, to coordinate our efforts, and even to contemplate our own demise. Linguistic anthropologists ask questions like: How did language first emerge? How has it evolved and diversified over time? How has language helped us succeed as a species? How can language convey one’s social identity? How does language influence our views of the world?

If you speak two or more languages, you may have experienced how language affects you. For example, in English, we say: “I love you.” But Spanish speakers use different terms—te amo, te adoro, te quiero, and so on—to convey different kinds of love: romantic love, platonic love, maternal love, etc. The Spanish language arguably expresses more nuanced views of love than the English language.

One intriguing line of linguistic anthropological research focuses on the relationship between language, thought, and culture. It may seem intuitive that our thoughts come first; after all, we like to say: “Think before you speak.” However, according to the Sapir-Whorf Hypothesis (also known as linguistic relativity), the language you speak allows you to think about some things and not others. When Benjamin Whorf (1897-1941) studied the Hopi language, he found not just word-level differences, but grammatical differences between Hopi and English. He wrote that Hopi has no grammatical tenses to convey the passage of time. Rather, the Hopi language indicates whether or not something has “manifested.” Whorf argued that English grammatical tenses (past, present, future) inspire a linear sense of time, while Hopi language, with its lack of tenses, inspires a cyclical experience of time (Whorf 1956).

Some critics, like German-American linguist Ekkehart Malotki, refute Whorf’s theory, arguing that Hopi do have linguistic terms for time and that a linear sense of time is natural and perhaps universal. At the same time, Malotki recognized that English and Hopi tenses differ, albeit in ways less pronounced than Whorf proposed (Malotki 1983). Other linguistic anthropologists track the emergence and diversification of languages, while others focus on language use in today’s social contexts. Still others explore how language is crucial to socialization: children learn their culture and social identity through language and nonverbal forms of communication (Ochs and Schieffelin 2012).

Quick Reading Check: What is linguistic anthropology and what elements of communication are they interested in?

1.4.4 Applied Anthropology

Applied anthropology involves the application of anthropological theories, methods, and findings to solve practical problems. Applied anthropologists are employed outside of academic settings, in both the public and private sectors, including business or consulting firms, advertising companies, city government, law enforcement, the medical field, non governmental organizations, and even the military.

Applied anthropologists span all four of the subfields. An applied archaeologist might work in cultural resource management to assess a potentially significant archaeological site unearthed during a construction project. An applied cultural anthropologist could work at a technology company that seeks to understand the human-technology interface in order to design better tools.

Medical anthropology is an example of both an applied and theoretical area of study that draws on all four subdisciplines to understand the interrelationship of health, illness, and culture. Rather than assume that disease resides only within the individual body, medical anthropologists explore the environmental, social, and cultural conditions that impact the experience of illness. For example, in some cultures, people believe illness is caused by an imbalance within the community. Therefore, a communal response, such as a healing ceremony, is necessary to restore both the health of the person and the group. This approach differs from the one used in mainstream U.S. healthcare, whereby people go to a doctor to find the biological cause of an illness and then take medicine to restore the individual body. Trained as both a physician and medical anthropologist, the late Paul Farmer demonstrates the applied potential of anthropology. During his college years in North Carolina, Farmer’s interest in the Haitian migrants working on nearby farms inspired him to visit Haiti. There, he was struck by the poor living conditions and lack of health care facilities. Later, as a physician, he would return to Haiti to treat individuals suffering from diseases like tuberculosis and cholera that were rarely seen in the United States. As an anthropologist, he would contextualize the experiences of his Haitian patients in relation to the historical, social, and political forces that impact Haiti, the poorest country in the Western Hemisphere (Farmer 2006). He died in February 2022, but his academic writing and his activism in the world live on through the people he has inspired and the work of Partners in Health, a nonprofit organization that he co-founded. He helped open health clinics in many resource-poor countries and trained local staff to administer care. In this way, he applied his medical and anthropological training to improve people’s lives.

Quick Reading Check: How does applied anthropology differ from academic anthropology?

1.5 How Did Anthropology Come to Be?

Imagine you are living several thousand years ago. Maybe you are a parent of three children. Maybe you are a young individual eager to start your own family. Maybe you are a prominent religious leader, or maybe you are a respected healer. Your family has, for as long as people can remember, lived the way you do. You learned to act, eat, hunt, talk, pray, and live the way you do from your parents, your extended family, and your small community. Suddenly, you encounter a new group of people who have a different way of living, speak strangely, and eat in an unusual manner. They have a different way of addressing the supernatural and caring for their sick. What do you make of these differences? These are the questions that have faced people for tens of thousands of years as human groups have moved around and settled in different parts of the world.

One of the first examples of someone who attempted to systematically study and document cultural differences is Zhang Qian (164 BC – 113 BC). Born in the second century BCE in Hanzhong, China, Zhang was a military officer who was assigned by Emperor Wu of Han to travel through Central Asia, going as far as what is today Uzbekistan. He spent more than twenty-five years traveling and recording his observations of the peoples and cultures of Central Asia (Wood 2004). The Emperor used this information to establish new relationships and cultural connections with China’s neighbors to the West. Zhang discovered many of the trade routes used in the Silk Road and introduced several new cultural ideas, including Buddhism, into Chinese culture. Another early traveler of note was Abu Abdullah Muhammad Ibn Battuta, known most widely as Ibn Battuta, (1304-1369). Ibn Battuta was an Amazigh (Berber) Moroccan Muslim scholar. During the fourteenth century, he traveled for a period of nearly thirty years, covering almost the whole of the Islamic world, including parts of Europe, sub-Saharan Africa, India, and China. Upon his return to the Kingdom of Morocco, he documented the customs and traditions of the people he encountered in a book called Tuhfat al-anzar fi gharaaib al-amsar wa aja’ib al-asfar (A Gift to those who Contemplate the Wonders of Cities and the Marvels of Traveling), a book commonly known as Al Rihla, which means “travels” in Arabic (Mackintosh-Smith 2003: ix). This book became part of a genre of Arabic literature that included descriptions of the people and places visited along with commentary about the cultures encountered. Some scholars consider Al Rihla to be among the first examples of early pre-anthropological writing.[3]

The stories of Zhang Qian and Abu Abdullah Muhammad are particularly important for us to learn about because of the common erasure of non-white, non-European, and non-Greco-Roman peoples in the telling of history and in the development of many of our academic disciplines. Even I (Vanessa Martinez) only recently learned about these two scholars and their importance to anthropological history and I have been a professor of anthropology for over sixteen years.

Later, from the 1400s through the1700s, during the so-called “Age of Discovery,” Europeans began to explore the world and then colonize it. Europeans exploited natural resources and human labor in other parts of the world, exerting social and political control over the people they encountered. New trade routes along with the slave trade fueled a growing European empire while forever disrupting previously independent cultures in the Old World. European ethnocentrism—the belief that one’s own culture is better than others—was used to justify the subjugation of non-European societies on the alleged basis that these groups were socially and even biologically inferior. Indeed, the emerging anthropological practices of this time were ethnocentric and often supported colonial projects. As European empires expanded, new ways of understanding the world and its people arose. Beginning in the eighteenth century in Europe, the Age of the Enlightenment was a social and philosophical movement that privileged science, rationality, and experience while critiquing religious authority. This crucial period of intellectual development planted the seeds for many academic disciplines, including anthropology. It gave ordinary people the capacity to learn the “truth” through observation and experience: anyone could ask questions and use rational thought to discover things about the natural and social world.

For example, geologist Sir Charles Lyell (1797-1875) observed layers of rock and argued that the earth’s surface must have changed gradually over long periods of time. He disputed the Young Earth theory, which was popular at the time and used Biblical information to date the earth as only 6,000 years old, Charles Darwin (1809-1882), a naturalist and biologist, observed similarities between fossils and living specimens, leading him to argue that all life is descended from a common ancestor. Philosopher John Locke (1632-1704) contemplated the origins of society itself, proposing that people historically had lived in relative isolation until they agreed to form a society in which the government would protect their personal property.

These radical ideas about the earth, evolution, and society influenced early social scientists into the nineteenth century. Philosopher and anthropologist Herbert Spencer (1820-1903), inspired by scientific principles, used biological evolution as a model to understand social evolution. Just as biological life evolved from simple to complex multicellular organisms, he postulated that societies “evolve” to become larger and more complex. Like Herbert Spencer, anthropologist Lewis Henry Morgan (1818-1881) was a proponent of social evolution and argued that all societies “progress” through the same stages of development: savagery—barbarism—civilization. Societies were classified into these stages based on their family structure, technologies, and methods for acquiring food. So-called “savage” societies, ones that used stone tools and foraged for food, were said to be stalled in their social, mental, and even moral development.

Ethnocentric ideas like Spencer’s and Morgan’s were challenged by anthropologists in the early twentieth century in both Europe and the United States. During World War I, Bronislaw Malinowski (1884-1942), a Polish anthropologist, became stranded on the Trobriand Islands located north of Australia and Papua, New Guinea. While there, he started to develop participant-observation fieldwork: the method of immersive, long-term research that cultural anthropologists use today. By living with and observing the Trobriand Islanders, he realized that their culture was not “savage” but was well-suited to fulfill the needs of the people. He developed a theory to explain human cultural diversity: each culture functions to satisfy the specific biological and psychological needs of its people. While this theory has been critiqued as biological reductionism, it was an early attempt to view other cultures in more open-minded ways. Around the same time in the United States, Franz Boas (1858-1942), widely regarded as the founder of American anthropology, developed cultural relativism, the view that while cultures differ, they are not better or worse than one another. In his critique of ethnocentric views, Boas insisted that physical and behavioral differences among racial and ethnic groups in the United States were shaped by environmental and social conditions, not biology. In fact, he argued that culture and biology are distinct realms of experience: human behaviors are socially learned, contextual, and flexible but not innate. Further, Boas worked to transform anthropology into a professional and empirical academic discipline that integrated the four subdisciplines of cultural anthropology, linguistic anthropology, archaeology, and biological anthropology.

1.6 Picture of an Anthropologist: Anthony Kwame Harrison

I (Kwame) like to tell a story about how, on the last day of my first year at the University of Massachusetts, while sitting alone in my dorm room waiting to be picked up, I decided to figure out what my major would be. So, I opened the course catalog—back then it was a physical book—and started going through it alphabetically.

On days when I am feeling particularly playful, I say that after getting through the A’s, I knew anthropology was for me. In truth, I also considered Zoology. I was initially drawn to anthropology because of its traditional focus on exoticness and difference. I was born in Ghana, West Africa, where my American father had spent several years working with local artisans at the National Cultural Centre in Kumasi. My family moved to the United States when I was still a baby and I had witnessed my Asante mother struggle with adapting to certain aspects of life in America.

Studying anthropology, then, gave me a reason to learn more about the unusual artwork that filled my childhood home and to connect with a faraway side of my family that I hardly knew anything about.

Looking through that course catalog, I didn’t really know what anthropology was but resolved to test the waters by taking several classes the following year. As I flourished in these courses—two introductory level classes on cultural anthropology and archeology, a class called “Culture through Film,” and another on “Egalitarian Societies”—I envisioned a possible future as an anthropologist working in rural West Africa on topics like symbolic art and folklore. I never imagined I would earn a Ph.D. researching the mostly middle-class, largely multi-racial, independent hip-hop scene in the San Francisco Bay Area.

Through my anthropological training, I have made a career exploring how race influences our perceptions of popular music. I have written several pieces on racial identity and hip hop—most notably my 2009 book, Hip Hop Underground: The Integrity and Ethics of Racial Identification. I have also explored how race impacts people’s senses of belonging in various social spaces—for instance, African American participation in downhill skiing or the experiences of underrepresented students at historically white colleges and universities. In all these efforts, my attention is primarily on understanding the complexities, nuances, and significance of race. I use these other topics—music, recreation, and higher education—as avenues through which to explore race’s multiple meanings and unequal consequences.

Where a fascination with the exotic initially brought me to anthropology, it is the discipline’s ability to shed light on what many of us see as normal, common, and taken-for-granted that has kept me with it through three degrees (bachelor’s, master’s, and Ph.D.) and a fifteen-year career as a college professor. I am currently the Gloria D. Smith Professor of Africana Studies at Virginia Tech—a school that, oddly enough, does not have an anthropology program. Being an anthropologist at a major university that doesn’t have an anthropology program, I believe, gives me a unique perspective on the discipline’s key virtues.

One of the most important things that anthropology does is create a basis for questioning taken-for granted notions of progress. Does the Gillette Fusion Five Razor, with its five blades, really offer a better shave than the four-bladed Schick Quattro? I cannot say for sure, but as I’ve witnessed the move from twin-blade razors, to Mach 3s, to today (there is even a company offering “the world’s first and only” razor with “seven precision aligned blades)” there appears to be a presumption that more, in this case, razor-blades is better. I’ll admit that the razor-blade example is somewhat crude. Expanding out to the latest model automobile or smartphone, people seem to have a seldom questioned belief in the notion that newer technologies ultimately improve our lives. Anthropology places such ideas within the broader context of human lifeways, or what anthropologists call culture. What are the most crucial elements of human biological and social existence? What additional developments have brought communities the greatest levels of collective satisfaction, effective organization, and sustainability?

Anthropology has taught me to view the contemporary American lifestyle that I grew up think ing was normal through the wider frame of humanity’s long history. How does our perspective change upon learning that for the vast majority of human history—some say as much as ninety nine percent of it—people lived a foraging lifestyle (commonly referred to as “hunting and gathering”)? Although I am not calling for a mass return to foraging, when we consider the significant worldwide issues that humans face today—such things as global warming, the threat of nuclear war, accelerating ethnic conflicts, and a world population that has grown from one billion to nearly eight billion over the past two hundred years—we are left with difficult questions about whether 10,000 years of agriculture and a couple hundred years of industrialization have been in humanity’s best long-term interests. All of this is to say that anthropology offers one of the most biting critiques of modernity, which challenges us to slow down and think about whether the new technologies we are constantly being presented with make sense. Similarly, the anthropological concept of ethnocentrism is incredibly useful when paired with different examples of how people define family, recognize leadership, decide what is and is not edible, and the like.Using my own anthropological biography as an illustration, I want to stress that the discipline does not showcase diverse human lifeways to further exoticize those who live differently from us. In contrast, anthropology showcases cultural variation to illustrate the possibilities and potential for human life, and to demonstrate that the way of doing things we know best is neither normal nor necessarily right. It is just one way among a multitude of others. “Everybody does it but we all do it different”; this is culture.

Quick Reading Check: What did you learn about the discipline of anthropology by reading Kwame’s story?

1.7 What Makes Anthropology Unique From Other Social Sciences?

Humanity, while central to anthropology, is not only studied in anthropology. Other social sciences, sociology and psychology most notably often discuss similar concepts like the role of culture and ask similar questions about the past, societies, and human nature. Students often ask what is unique about anthropology and how it differs from the other social sciences. Anthropologists across the subfields use unique perspectives to conduct their research that make anthropology distinct from related disciplines — like history, sociology, and psychology.

These key anthropological perspectives are holism, relativism, comparison, and fieldwork. Important to all of these perspectives are how different anthropologists might use scientific strategies and humanistic frameworks to better understand the world, and at times, conflict with one another.

1.7.1 Holism

Anthropologists are interested in the whole of humanity and how various aspects of life interact. One cannot fully appreciate what it means to be human by studying a single aspect of our complex histories, languages, bodies, or societies. By using a holistic approach, anthropologists ask how different aspects of human life influence one another. For example, a cultural anthropologist studying the meaning of marriage in a small village in India might consider local gender norms, existing family networks, laws regarding marriage, religious rules, and economic factors. A biological anthropologist studying monkeys in South America might consider the species’ physical adaptations, foraging patterns, ecological conditions, and interactions with humans in order to answer questions about their social behaviors. By understanding how nonhuman primates behave, we discover more about ourselves (after all, humans are primates!). By using a holistic approach, anthropologists reveal the complexity of biological, social, or cultural phenomena.

Anthropology itself is a holistic discipline, composed in the United States (and in some other nations) of four major subfields: cultural anthropology, biological anthropology, linguistic anthropology, and archaeology. While anthropologists often specialize in one subfield, their specific research contributes to a broader understanding of the human condition, which is made up of culture, language, biological and social adaptations, as well as human origins and evolution.

1.7.2 Cultural Relativism (versus Ethnocentrism)

The guiding philosophy of modern anthropology is cultural relativism—the idea that we should seek to understand another person’s beliefs and behaviors from the perspective of their culture rather than our own. Anthropologists do not judge other cultures based on their values nor do they view other ways of doing things as inferior. Instead, anthropologists seek to understand people’s beliefs within the system they have for explaining things.

The opposite of cultural relativism is ethnocentrism, the tendency to view one’s own culture as the most important and correct and as a measuring stick by which to evaluate all other cultures that are largely seen as inferior and morally suspect. As it turns out, many people are ethnocentric to some degree; ethnocentrism is a common human experience. Why do we respond the way we do? Why do we behave the way we do? Why do we believe what we believe? Most people find these kinds of questions difficult to answer. Often the answer is simply “because that is how it is done.” But the answer should be expanded to – “that is the way it is done in our culture at this time” – acknowledging both its cultural context and its time-bound nature. People typically believe that their ways of thinking and acting are “normal”; however, at a more extreme level, some believe their ways are better than those of others.

Ethnocentrism is not a useful perspective in contexts in which people from different cultural backgrounds come into close contact with one another, as is the case in many cities and communities throughout the world. People increasingly find that they must adopt culturally relativistic perspectives in governing communities and as a guide for their interactions with members of the community. For anthropologists, cultural relativism is especially important. We must set aside our innate ethnocentric views in order to allow cultural relativism to guide our inquiries and interactions so that we can learn from others.

1.7.3 The Comparative Approach

Anthropologists of all the subfields use comparison to learn what humans have in common, how we differ, and how we change. Anthropologists ask questions like: How do chimpanzees differ from humans? How do different languages adapt to new technologies? How do countries respond differently to immigration? In cultural anthropology, we compare ideas, morals, practices, and systems within or between cultures. We might compare the roles of men and women in different societies or contrast how different religious groups conflict within a given society. Like other disciplines that use comparative approaches, such as sociology or psychology, anthropologists make comparisons between people in a given society. Unlike these other disciplines, anthropologists also compare across societie and between humans and other primates. In essence, anthropological comparisons span societies, cultures, time, place, and species. It is through comparison that we learn more about the range of possible responses to varying contexts and problems.

1.7.4 Fieldwork

Anthropologists conduct their research in the field with the species, civilization, or groups of people they are studying. In cultural anthropology, our fieldwork is referred to as ethnography, which is both the process and result of cultural anthropological research. The Greek term “ethno” refers to people, and “graphy” refers to writing. The ethnographic process involves the research method of participant observation fieldwork: you participate in people’s lives, while observing them and taking field notes that, along with interviews and surveys, constitute the research data. This research is inductive: based on day-to-day observations, the anthropologist asks increasingly specific questions about the group or about the human condition more broadly. Oftentimes, informants actively participate in the research process, helping the anthropologist ask better questions and understand different perspectives.

The word ethnography also refers to the end result of our fieldwork. Cultural anthropologists do not write “novels,” rather they write ethnographies, descriptive accounts of culture that weave detailed observations with theory. After all, anthropologists are social scientists. While we study a particular culture to learn more about it and to answer specific research questions, we are also exploring fundamental questions about human society, behavior, or experiences.

In the course of conducting fieldwork with human subjects, anthropologists invariably encounter ethical dilemmas: Who might be harmed by conducting or publishing this research? What are the costs and benefits of identifying individuals involved in this study? How should one resolve competing interests of the funding agency and the community? To address these questions, anthropologists are obligated to follow a professional code of ethics that guide us through ethical considerations in our research.[4]

Quick Reading Check: What are the four anthropological perspectives that are used to distinguish anthropology from other social sciences?

1.7.5 Scientific vs Humanistic Approaches

As you may have noticed from the above discussion of the anthropological sub-disciplines, anthropologists are not unified in what they study or how they conduct research. Some sub-disciplines, like biological anthropology and archaeology, use a deductive, scientific approach. Through hypothesis testing, they collect and analyze material data (e.g. bones, tools, seeds, etc.) to answer questions about human origins and evolution. Other subdisciplines, like cultural anthropology and linguistic anthropology, use humanistic and/or inductive approaches to their collection and analysis of nonmaterial data, such as observations of everyday life or language in use.

At times, tension has arisen between the scientific subfields and the humanistic ones. For example, in 2010, some cultural anthropologists critiqued the American Anthropological Association’s mission statement, which stated that the discipline’s goal was “to advance anthropology as the science that studies humankind in all its aspects.”[5] These scholars wanted to replace the word “science” with “public understanding.” They argued that some anthropologists do not use the scientific method of inquiry; instead, they rely more on narratives and interpretations of meaning. After much debate, the word “science” remains in the mission statement and, throughout the United States, anthropology is predominantly categorized as a social science.

1.8 Why is Anthropology Important?

As we hope you have learned thus far, anthropology is an exciting and multifaceted field of study. Because of its breadth, students who study anthropology go on to work in a wide variety of careers in medicine, museums, field archaeology, historical preservation, education, international business, documentary filmmaking, management, foreign service, law, and many more. Beyond preparing students for a particular career, anthropology helps people develop essential skills that are transferable to many career choices, life paths, and interpersonal relationships. Studying anthropology fosters broad knowledge of other cultures, skills in observation and analysis, critical thinking, clear communication, and applied problem-solving. Anthropology encourages us to extend our perspectives beyond familiar social contexts to view things from the perspectives of others. As one former cultural anthropology student observed, “I believe an anthropology course has one basic goal: to eliminate ethnocentrism. A lot of issues we have today (racism, xenophobia, etc.) stem from the toxic idea that people are ‘other’. We must put that idea aside and learn to value different cultures.”[6] This anthropological perspective is an essential skill for nearly any career in today’s globalized world.

Discussion Questions

1. This chapter emphasizes how broad the discipline of anthropology is and how many different kinds of research questions anthropologists in the four subdisciplines pursue. What do you think are the strengths or unique opportunities of being such a broad discipline? What are some challenges or difficulties that could develop in a discipline that studies so many different things?

2. Cultural anthropologists focus on the way beliefs, practices, and symbols bind groups of people together and shape their worldview and lifeways. Thinking about your own culture, what is an example of a belief, practice, or symbol that would be interesting to study anthropologically? What do you think could be learned by studying the example you have selected?

3. Discuss the definition of culture proposed in this chapter. How is it similar or different from other ideas about culture that you have encountered in other classes or in everyday life?

4. In this chapter, Anthony Kwame Harrison describes how he first became interested in anthropology and how he has used his training in anthropology to conduct research in different parts of the world. How do you think the participant-observation fieldwork he described leads to information that would otherwise be difficult or impossible to learn?

5. In this chapter, [blank] and [blank], former anthropology students, discuss the lifelong lessons learned in their anthropology courses and the “pay it forward” effect it has had in their communities. Whose story resonated with you and why? Are you open to letting a course change your life?

Glossary

Cultural relativism: the idea that we should seek to understand another person’s beliefs and behaviors from the perspective of their own culture and not our own.

Deductive: reasoning from the general to the specific; the inverse of inductive reasoning. Deductive research is more common in the natural sciences than in anthropology. In a deductive approach, the researcher creates a hypothesis and then designs a study to prove or disprove the hypothesis. The results of deductive research can be generalizable to other settings.

Enculturation: the process of learning the characteristics and expectations of a culture or group. Ethnocentrism: the tendency to view one’s own culture as most important and correct and as the ruler by which to measure all other cultures.

Ethnography: the in-depth study of the everyday practices and lives of a people.

Hominin: Humans (Homo sapiens) and their close relatives and immediate ancestors.

Inductive: a type of reasoning that uses specific information to draw general conclusions. In an inductive approach, the researcher seeks to collect evidence without trying to definitively prove or disprove a hypothesis. The researcher usually first spends time in the field to become familiar with the people before identifying a hypothesis or research question. Inductive research usually is not generalizable to other settings.

Paleoanthropologist: biological anthropologists who study ancient human relatives. Participant-observation: a type of observation in which the anthropologist observes while participating in the same activities in which her informants are engaged.

Bibliography

Berger, Lee R., Hawks, John, de Ruiter, Darryl J., Churchill, Steven E., Schmid, Peter, Delezene, Lucas K., Kivell, Tracy L., Garvin, Heather M., and Scott A. Williams. 2015. “Homo naledi, A New Species of the Genus Homo from the Dinaledi Chamber, South Africa.” eLife 4:e09560. doi: 10.7554/eLife.09560. Bourgois, Philippe. In Search of Respect: Selling Crack in El Barrio. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2003.

Briggs, Jean. Never in Anger: Portrait of an Eskimo Family. Cambridge: President and Fellows of Harvard College, 1970.

Farmer, Paul. AIDS and Accusation: Haiti and the Geography of Blame. Berkeley: University of California Press, 2006.

Goodall, Jane. My Life with the Chimpanzees. New York: Aladdin Paperbacks, 1996. Harrison, Anthony Kwame. Hip Hop Underground: The Integrity and Ethics of Racial Identification. Philadel phia: Temple University Press, 2009.

Jablonski, Nina. Living Color: The Biological and Social Meaning of Skin Color. Berkeley: University of Cal ifornia Press, 2012.

Kenyon, Kathleen. Excavations at Jericho – Volume II Tombs Excavated in 1955-8, London: British School of Archaeology, 1965.

Kwiatkowski, Lynn. Struggling with Development: The Politics of Hunger and Gender in the Philippines. Boulder: Westview Press, 1998.

Mackintosh-Smith, Tim, ed. The Travels of Ibn Battutah. London: Picador, 2003.

Malotki, Ekkehart. Hopi Time: A Linguistic Analysis of the Temporal Concepts in the Hopi Language. Trends in Linguistics. Studies and Monographs. 20. New York: Mouton Publishers, 1983. Mackintosh-Smith, Tim, ed. The Travels of Ibn Battutah. London: Picador, 2003.

Ochs, Elinor, and Bambi B. Schieffelin. 2012. “The Theory of Language Socialization.” In The Handbook of Language Socialization edited by Alessandro Duranti, Elinor Ochs, and Bambi Schieffelin, 1–21. Malden, MA: Wiley-Blackwell, 2012.

Rathje, William and Cullen Murphy. Rubbish: The Archaeology of Garbage. New York: HarperCollins Pub lishers, 1992.

Whorf, Benjamin Lee. Language, Thought, and Reality: Selected writings of Benjamin Lee Whorf. Edited by J.B. Carroll. Cambridge: M.I.T Press, 1956.

Wood, Frances. The Silk Road: Two Thousand Years in the Heart of Asia. Berkeley: University of California Press, 2004.

About the Original Authors

Katie Nelson is an instructor of anthropology at Inver Hills Community College. Her research focuses on migration, identity, belonging, and citizenship(s) in human history and in the contemporary United States, Mexico, and Morocco. She received her B.A. in anthropology and Latin American studies from Macalester College, her M.A. in anthropology from the University of California, Santa Barbara, an M.A. in education and instructional technology from the University of Saint Thomas, and her Ph.D. from CIESAS Occidente (Centro de Investigaciones y Estudios Superiores en Antropologia Social –Center for Research and Higher Education in Social Anthropology), based in Guadalajara, Mexico.

Katie views teaching and learning as central to her practice as an anthropologist and as mutually reinforcing elements of her professional life. She is the former chair of the Teaching Anthropology Interest Group (2016–2018) of the General Anthropology Division of the American Anthropological Association and currently serves as the online content editor for the Teaching and Learning Anthropology Journal. She has contributed to several open access textbook projects, both as an author and an editor, and views the affordability of quality learning materials as an important piece of the equity and inclusion puzzle in higher education.10

Lara Braff is an instructor of anthropology at Grossmont College, where she teaches cultural and biological anthropology courses. She received her B.A. in anthropology and Spanish from the University of California at Berkeley and both her M.A. and Ph.D. in comparative human development from the University of Chicago, where she specialized in cultural and medical anthropology. Her research has focused on social identities and disparities in the context of reproduction and medicine in both Mexico and the U.S.

Lara’s concern about social inequality has guided her research projects, teaching practices, and involvement in open access projects like this textbook. In an effort to make college more accessible to all students, she serves as co-coordinator of Grossmont College’s Open Educational Resources (OER) and Zero Textbook Cost (ZTC) initiatives.

Media Attributions

- Private: Anthropology subfields © Vanessa Martínez is licensed under a CC BY-NC-SA (Attribution NonCommercial ShareAlike) license

- Private: Anthony Kwame Harrison © Virginia Tech University is licensed under a All Rights Reserved license

- Private: Harrison Perform © Kwame Harrison is licensed under a All Rights Reserved license

- Private: Katie Nelson fieldwork © Katie Nelson is licensed under a CC BY-NC (Attribution NonCommercial) license

- Private: Katie Nelson © Katie Nelson is licensed under a CC BY-NC-SA (Attribution NonCommercial ShareAlike) license

- See: https://www.americananthro.org/LearnAndTeach/ResourceDetail.aspx?ItemNumber=1499). ↵

- https://www.nps.gov/afbg/index.htm ↵

- Lahcen Mourad (Arabic scholar) in discussion with Katie Nelson, December, 2018. ↵

- See the American Anthropological Association’s Code of Ethics: http://ethics.americananthro.org/category/statement/ ↵

- See: American Anthropological Association Statement of Purpose: https://www.americananthro.org/Con nectWithAAA/Content.aspx?ItemNumber=1650 ↵

- This quote is taken from a survey of students in an Introduction to Cultural Anthropology course at the Community College of Baltimore County, 2018. ↵

Humans (Homo sapiens) and their close relatives and immediate ancestors.

biological anthropologists who study ancient human relatives. Participant-observation: a type of observation in which the anthropologist observes while participating in the same activities in which her informants are engaged.

The idea that we should seek to understand another person’s beliefs and behaviors from the perspective of their own culture and not our own.

the in-depth study of the everyday practices and lives of a people.

a type of reasoning that uses specific information to draw general conclusions. In an inductive approach, the researcher seeks to collect evidence without trying to definitively prove or disprove a hypothesis. The researcher usually first spends time in the field to become familiar with the people before identifying a hypothesis or research question. Inductive research usually is not generalizable to other settings.

reasoning from the general to the specific; the inverse of inductive reasoning. Deductive research is more common in the natural sciences than in anthropology. In a deductive approach, the researcher creates a hypothesis and then designs a study to prove or disprove the hypothesis. The results of deductive research can be generalizable to other settings.