The Rise of Anti-Diet Culture

Ireena Haque

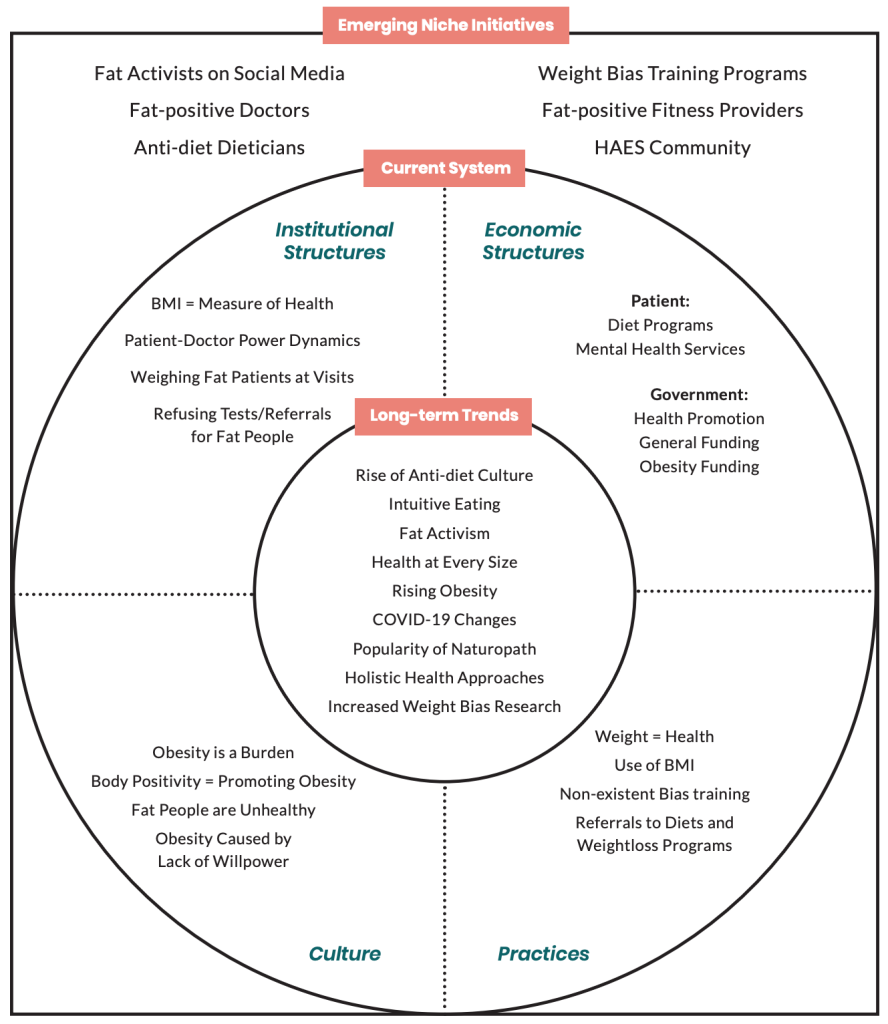

Rich Context Tool

Long-term Trends

Around the general landscape of weight bias, some long-term trends are emerging.

These could have a potential influence on the issue and a positive impact on fixing the issue. The trends include:

Rise of Anti-diet Culture

While the dieting industry in the United States is estimated to be worth 72 billion dollars (Market Data LLC, 2019), diet-culture resistance is a growing trend. The anti- diet movement spearheaded by intuitive eating practices is a way of thinking about eating that takes you back to babyhood when you ate what you wanted for as long as you wanted and when full, turned away (LaMotte, 2020). It discourages restricting food groups and food items, which is a standard in dieting plans. The notion is that if you allow yourself to eat everything whenever you crave it, you will be able to prevent yourself from overeating and falling into unhealthy eating habits. Dieting is standard advice given by doctors to their fat patients. Some doctors will give the usual “eat less, move more” lecture (“Obesity Not Defined,” 2020), and others will refer patients to specific dieting programs or clinics, whether the patients want to or not. However, the data show that 95% of people who go on diets fail at them, and if they have lost weight, two-thirds of them gain even more weight back (LaMotte, 2020). With the rise of this trend, patients are more exposed to intuitive eating habits and benefits. Therefore, it can have a positive effect on biased dieting advice from doctors, as more and more patients refuse to follow them.

Health at Every Size Ideologies

Anti-diet culture is one of the underpinnings of the Health at Every Size movement. It is a movement working to promote size acceptance, end weight discrimination, and lessen the cultural obsession with weight loss and thinness. The HAES movement promotes balanced eating, life- enhancing physical activity, and respect for the diversity of body shapes and sizes (Association of Size Diversity and Health, 2020).

Anti-diet culture is one of the underpinnings of the Health at Every Size movement. It is a movement working to promote size acceptance, end weight discrimination, and lessen the cultural obsession with weight loss and thinness. The HAES movement promotes balanced eating, life- enhancing physical activity, and respect for the diversity of body shapes and sizes (Association of Size Diversity and Health, 2020).

This approach proposes that any intervention strategy for obesity should be one that promotes the development of a healthy lifestyle (Penney & Kirk, 2015). While many critics might accuse this way of thinking as ‘glorifying’ obesity, which they only see as unhealthy, the HAES culture is slowly trending upwards and giving fat patients more empowerment to stand up for their health and body in biased settings.

Test Your Understanding

Fat-positive Activism

The rise of anti-diet and HAES movements has propelled the rise of fat-positive activism. Fat-positive or fat acceptance movements have been around since the 1960s. It has been around through different waves and forms for about 50 years, but currently, fat acceptance is a social justice movement aiming to make body culture more inclusive and diverse in all its forms (Severson, 2019).

The rise of anti-diet and HAES movements has propelled the rise of fat-positive activism. Fat-positive or fat acceptance movements have been around since the 1960s. It has been around through different waves and forms for about 50 years, but currently, fat acceptance is a social justice movement aiming to make body culture more inclusive and diverse in all its forms (Severson, 2019).

With the rise of social media and influencer roles, the movement has skyrocketed in popularity. Fat acceptance supports the equal rights of fat bodies in all aspects of life, including healthcare. Hence, it has the ability to have immense effects on the stigmatized treatment of larger bodies by healthcare providers.

Rising Rates of Obesity

The rise of positive movements has not yet made its effect on the daily systemic structures in which fat people face prejudice because of their weight. Weight bias is more ubiquitous than ever, especially in healthcare, with providers and researchers believing they are taking the right approach. However, rates of obesity continue to rise. If diets work, weight loss programs work, and ‘tough-love’ care works, why is obesity continuing to increase? The rate of obesity has tripled over the past three decades in Canada, and now about one-in-four Canadians are obese, according to Statistics Canada (“Obesity not defined,” 2020). Furthermore, is obesity really the issue since it is a construct of BMI? Or, could we attribute the issue to the poor health of fat people caused by biased healthcare, socio-economic factors and societal stigma that prevents them from living and sustaining healthy lives? That is a conundrum that warrants a different research question, but it nevertheless influences this landscape.

Pandemic as a Catalyst for Healthcare Innovation

Lastly, the COVID-19 pandemic has completely revamped healthcare. It has revealed the gaps and shortcomings in the province’s healthcare system. In the past few months, the world has seen the pace of healthcare innovation accelerate rapidly, with the typical timeline of years becoming weeks or days. Under normal circumstances, healthcare innovation is costly and time-consuming. However, COVID-19 has pushed healthcare innovation to develop at unprecedented speed, with individuals focusing on solving real-world problems and collaborating with cross-functional teams (Palanica & Fossat, 2020). This is a fundamental shift that can positively affect the issue of weight bias. If this healthcare prioritization rate continues, the implementation of weight bias interventions will be much smoother.

Current System

In the current system of weight bias, the tool revealed the following structures and practices:

Economic Structures

The economic structures can be divided into two categories – patient expenses and government expenses. Due to weight bias, the patient may face additional costs in accessing dieting programs that doctors recommend. They may also face the cost of mental health resources that they require to treat harmful emotional effects from biased care. On the government side, rising rates of obesity are increasing expenditure. It is estimated that the economic costs of obesity in Canada range from $4.6 billion to $7.1 billion annually (Public Health Agency of Canada, 2011).

Cultural Structures

The cultural notions that exist in the current system include a plethora of biased beliefs that antagonize fat people. It is a common assumption that fat people are lazy and have no control over their appetite. They lack willpower, lead very unhealthy lives and are at high risk of mortality because of their own failures. Doctors’ explicit impressions of patients with obesity tend to be that they are non-compliant and sloppy (Alberga et al, 2016).

Institutional Structures

The structures in play that encourage weight bias in healthcare settings include the power dynamics between doctors and their patients. Doctors often exert control over their fat patients in the form of tests or referral refusal. This can be caused by an implicit bias rooted in another institutional structure that BMI is an accurate representation of health. This belief is strengthened in medical education. Studies show that explicit weight bias in medical students increases significantly during medical school (Phelan et al, 2015).

The structures in play that encourage weight bias in healthcare settings include the power dynamics between doctors and their patients. Doctors often exert control over their fat patients in the form of tests or referral refusal. This can be caused by an implicit bias rooted in another institutional structure that BMI is an accurate representation of health. This belief is strengthened in medical education. Studies show that explicit weight bias in medical students increases significantly during medical school (Phelan et al, 2015).

Practices

Common practices in the system currently are based on the belief that weight determines the health status of a patient. Referrals to diet and weight loss programs are expected and encouraged for all fat patients. Medical schools lack weight bias training, and there are currently no educational interventions actively at play (Poustchi et al, 2013).

Emerging Initiatives

While the current system appears to be discouraging regarding weight bias reduction actions, there are emerging initiatives on the horizon carried out by stakeholder groups such as influencers, HAES fitness providers and dieticians, and fat-positive doctors. There is no system-wide collaborative push, but individuals are working hard in the space to bring change.