Findings

Ireena Haque

As the participants navigated through each of the Horizon spaces and accompanying questions, the following findings emerged:

Horizon 1

What are the challenges fat patients face today when accessing healthcare?

- A lack of empathy from their doctors.

- A myriad of assumptions about their health habits and past weight loss attempts.

- Constant recommendation of losing weight no matter what the illness is.

- Fear of misdiagnoses.

- A battle to get referred for tests or to specialists.

- Mistrust from doctors on health habits and activities.

- Medical appointments being ‘hijacked’ by weight loss.

- Anxiety and hesitancy to get check-ups.

- A lot of exhausting efforts to research and prepare before appointments.

- Formal diagnoses on eating disorders.

- Physical barriers, particularly gowns, chairs and blood pressure cuffs.

Horizon 3

What is the desired future? What kind of changes do we want to see to make healthcare better for fat patients?

- Removal of BMI as a health assessment.

- Doctors who understand the harm of diet culture and fatphobia.

- Doctors who listen to fat people and show more empathy.

- Switching from an outcome-oriented healthcare model (weight loss) to a behavior- oriented one (healthy choices).

- Change in language around obesity. Neutralizing use of the word ‘fat.’

- Changed curriculum in medical school and extra required certification for existing doctors.

- Eating disorder diagnoses based on behaviors, not physical appearance.

- More qualitative research before obesity is listed as a risk factor in a disease. An example of this is the hasty decision to list obesity as a risk factor for COVID-19 with very little research on other factors such as race, socio-economic status, quality of care or other health conditions an individual might have (Byrne, 2020).

Horizon 2

What do we need to start doing to get to that desired future? What steps need to be taken, and who needs to take them?

- Bias training programs should focus on increasing empathy for fat patients in doctors.

- Health at Every Size training should be offered in medical schools or through continuing education.

- Change in curriculum in medical schools should be made to mandate a certain number of hours in weight bias training.

- Advocacy on a grassroots level and from healthcare providers is required.

- Recognizing fat healthcare workers, their contribution and experiences in the system.

- Academic research from all fields (social, economic, science) on weight bias.

- More education around eating disorders on all bodies is crucial.

- Removing morality from the discussion of health.

- Drafting health policy proposals to fight weight bias.

Secondary Spaces

What changes from our desired future are present today? Is change starting to happen?

- Empathetic fat-positive doctors already exist in some capacity.

- More and more advocacy is happening around condemning weight bias in healthcare.

- More fat inclusive languages are slowly being used in all settings.

Are there any aspects of the present day that we want to continue into our desired future?

- Academic research into weight bias has been rising in the last 15 years. Continuation of this research is required to fight the issue.

- Continuation of advocacy is essential to tackling the issue as there is a lot of pushback from society.

Who is already working to help us get to our desired future?

- The HAES community educates people on the importance of health, healthy living and behavior for all body sizes and weight.

- Canadian Eating Disorder Association makes people aware of the ‘atypical’ forms of eating disorder which include all the symptoms but in those who don’t match the physical description of the condition (“Other Specified,” 2019).

- Social media influencers use their platform to fight the issue and encourage fat positivity.

- Fat-positive fitness professionals who offer fitness coaching and classes for all bodies, making it easier for fat individuals to stay active.

- BalancedView BC provides online weight bias training program for the province’s health professionals (Balanced View, 2015).

Three Horizons Framework for Family Doctor

To complement the fat patient-centric framework, the Three Horizons exercise was also completed from a family doctor’s perspective. Since this was done individually by the researcher rather than in a workshop setting with doctor participants, some of the points are presumptive. Secondary research such as a detailed blog post written by an Ontario family doctor and news articles were used to produce the findings.

These sources contained information on the challenges family doctors face and how it negatively affects their practice. This helped in filling out the first horizon about today’s challenges. The desired future and transition points were then hypothesized based on these challenges. The main purpose of this exercise was to build more empathy for the family doctors and interpret their struggles and desires better.

What are the challenges family doctors in Ontario face today?

- Overwhelming workload. Too many patients and not enough family doctors, particularly outside of urban centers (Alam, 2018).

- Ongoing funding cuts by the Ontario government (Alam, 2018).

- Fewer medical school students are opting for family medicine, particularly clinic- based practice (Ray, 2017).

- Less integrated patient data system, especially in small towns (Alam, 2018).

- Family clinics are not backed up by a large institution, unlike hospitals (Kupfer, 2020).

- COVID-19 pandemic changes, particularly around personal protective equipment (PPE) shortage and adapting to virtual care (Kupfer, 2020).

What is the desired future? What kind of changes will improve family medicine?

- More new doctors in family practice.

- More medical school graduates specializing in family practice.

- More time to give to patients.

- Increased government funding focused on family medicine.

- A detailed, sophisticated data management system.

- More PPE during the pandemic and support from the government for post-pandemic changes.

What do we need to start doing to get to that desired future? What steps need to be taken, and who needs to take them?

- Medical school incentives to pursue family medicine.

- More funding and grants to start up a family practice.

- Research and funding to explore healthcare data management innovations.

- Start designing post-pandemic plans to anticipate changes and necessary resources.

Secondary Spaces

What changes from our desired future are present today? Is change starting to happen?

- Pandemic response and plans are being carried out by individual practitioners (Kupfer, 2020).

Are there any aspects of the present day that we want to continue into our desired future?

- Virtual care could continue on some level, depending on the patient issue, as it saves time and makes the clinic more efficient.

Who is already working to help us get to our desired future?

- Family clinics are banding together and forming support groups to help each other out.

Insights from Step 4

Completion of the Three Horizon frameworks, from the perspective of both primary actors, resulted in the following insights:

- The current challenges for fat patients are mostly embedded in assumptions made by healthcare providers and the mistrust between them and their fat patients.

- The desired future for fat patients is built on trust and understanding. Weight bias destroys that between a patient and their doctor. First and foremost, these patients want a better relationship with their doctors, followed by policy and protocol changes.

- The education sector and the government need to step into a more active role regarding this issue. The future can only be achieved with all nodes in the system working together.

- Current initiatives are only happening through individuals. Currently, there is no collective, collaborative change-making on the horizon.

- The desired future for family doctors is efficiency and more time for their patients. They want to run their practice and help their patients without the worries of funding cuts, a low number of family doctors, and a slow data management system.

Before diving into Step 5, it is critical to recap the last four steps and the insights they generated –

Step 1 analyzed the weight bias landscape by identifying structures, practices, trends, and stakeholders. This framed the project to focus on the two primary actors: fat patients and healthcare providers, and investigate how the other stakeholders affect them.

Step 2 investigated the primary actors through primary research and created Empathy Maps to better comprehend their perspectives and experiences with the issue of weight bias. Healthcare providers were further specified to be family doctors since primary research revealed that they are the biggest perpetrators of weight bias. This step generated insights about how external factors often augment doctors’ biased attitudes and that the most prominent tension between the doctor and the fat patient comes at the moment of diagnosis when the appointment is overpowered by talk of weight and weight loss.

Step 3 explored the main actors’ relationships with the secondary and examined the deeper causes of the issue. At the end of this step, it was evident that research around obesity was not perfect, focusing on quantitative figures rather than qualitative attributes. It was also exposed that there is a massive disconnect between the weight bias issue’s advocacy aspect and the scientific side of it.

Step 4 probed into the future state of the issue and what kind of changes are desired by the two primary actors. This step constructed the notion that the ultimate desired future is to have a more positive relationship between fat patients and their doctors.

While changes will need to be made in education and regulation, the betterment of the human relationship and partnership between the two primary actors is most coveted.

Now, in Step 5, with the help of the findings and insights discovered in the previous steps, possible ideas are formulated to address this project’s research question.

Intervention Strategy Model

The exploration of possibility spaces is initiated by using the Intervention Strategy Model from the Systemic Design Toolkit. This tool is based on the intervention levels determined by Donella Meadows. They refer to critical areas in a system in which one can intervene (Meadows, 1999). By exploring different possible interventions, one can make sure the future combination of interventions will cover the big picture (Systemic Design Toolkit, 2020). These intervention areas include the following: constants, parameters, buffering capacities, physical and digital structures, delays, balancing and reinforcing feedback loops, information flows, rules, self-organization, goals, and paradigms.

Possible Solution Spaces

The conglomeration of the insights from previous steps has ultimately led to the creation of four possible solution spaces.

Solution Space 1

Ontario Public Health policies regarding how overweight patients are treated in family medicine

The research has revealed that fat patients’ experience with their family doctors is brimming with weight bias. From physical barriers to staff attitudes and doctor diagnoses, every aspect is stressful, frustrating, and unfair for fat patients. However, there are currently no interventions present from a policy perspective to tackle the issue. By implementing formal guidelines on weight bias consequences and policies on tackling weight bias at the doctor’s office, fat patients can achieve fair treatment. This has the potential to decrease obesity mortality rates and advance the livelihoods of fat patients. The types of policies that can be introduced include simple notions such as:

- Weight cannot be the principal diagnosis for a fat patient’s issue since weight is not the sole cause of any illness. While obesity is considered a risk factor for many illnesses, not all people with obesity have the illnesses (“Health Risks Related,” n.d.).

- Non-invasive tests and referrals to specialists should be given without hesitation. The rule is simple. If the doctor is not referring the patient to tests or specialists because they think it is just a weight issue, then it is not a valid reason. This was a major complaint from the study participants.

- Adopt a behavior-oriented treatment model rather than an outcome-focused one. This remarkable idea was shared by one of the study participants. They described this model as doctors focusing more on their patients’ lifelong healthy behaviors versus pushing weight loss goals on them.

An underlying aim of policy development is to address health inequities and lessen the health gap (Bergeron, 2018), and biased treatment of a large portion of the population, resulting in many dire consequences, is undoubtedly a case of inequities in healthcare.

Solution Space 2

Adding in a weight bias curriculum in family medicine education across Ontario

There are currently six medical schools in Ontario (“Medical Schools,” 2020). After reviewing the publicly available foundational curriculum of all six schools, there was no evidence found of weight bias training or even courses on treating patients with obesity. With obesity rates in Ontario at over 26% (Statistics Canada, 2019), it is alarming that medical students coming out of schools in the province do not get any empathy training on treating fat patients.

The solution space prioritizes adding a weight bias curriculum in family medicine programs in Ontario medical schools. It can be passed on to other specializations later on. While the inclusion of this training should be mandatory, it can be part of electives to start with. This ensures that future graduates are more informed on the issue. For current professionals and those who fulfill medical education in other provinces or overseas, the proposal is to create weight bias certification courses through Continuing Studies at certain schools.

Solution Space 3

Increasing qualitative research on obesity as a condition and risk factor.

This possibility space puts forward the notion of slowing down and including more qualitative research into obesity as a risk factor. More research into social conditions, secondary illnesses, medical history, and economic conditions should be conducted before listing obesity as a risk factor for new diseases and further stigmatizing fat patients.

Solution Space 4

Removing weight management/dieting competing interests from any report or research on obesity

Weight management competing interests in research reports and health guidelines for obesity redact these materials’ academic validity. They contribute to sustained, biased healthcare. Removing these competing interests and avoiding contributions from such individuals or corporations will result in more dependable and viable research/ guidelines or, at least, maintain their scientific dignity.

The four solution spaces delve into four different sectors of the system – governance, education, research, and corporate involvement. If progress could be made in all these subsystems, overwhelming results could be achieved for the issue as a whole. However, if we travel back to the original research question, it aims to find answers to reducing weight bias in Ontario’s healthcare. Therefore, while solution spaces 3 and 4 champion significant proposals, they are much broader and not specific to Ontario. Solution spaces 1 and 2, on the other hand, include strategies that can definitely be put into action with stakeholders and resources in the province. Hence, this project will move forward with Solutions 1 and 2.

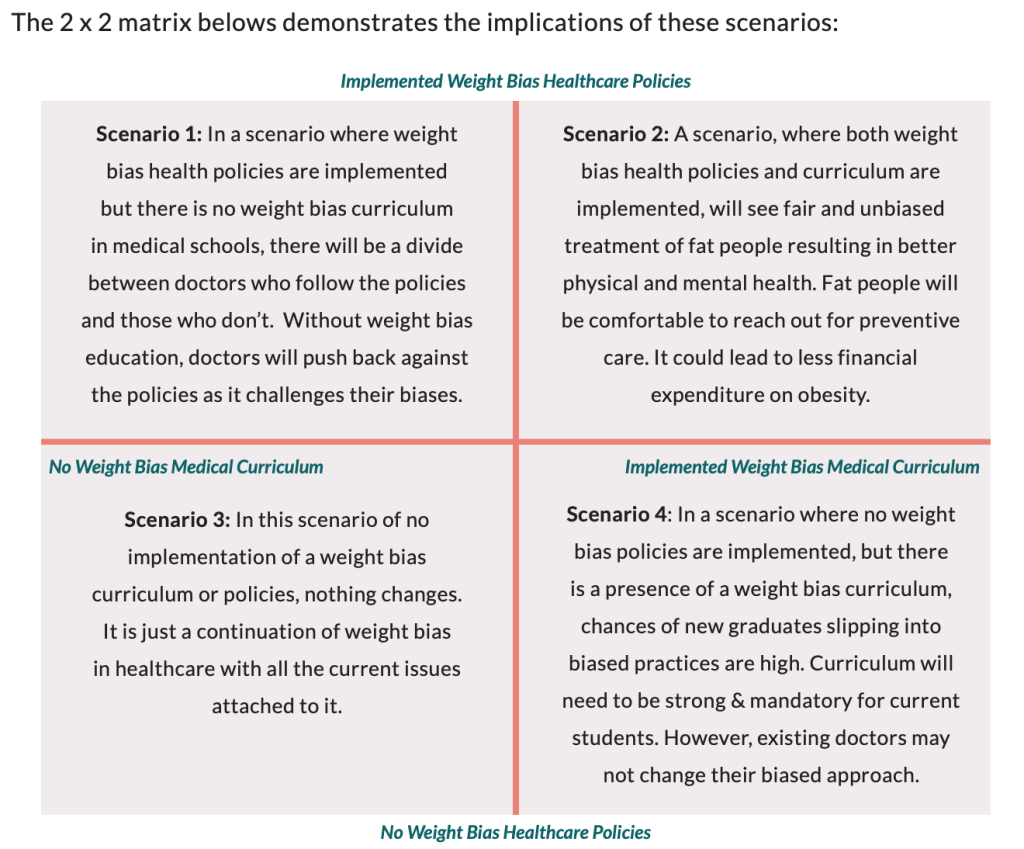

To further converge on a solution model, a quick future state scenario analysis was conducted through a 2 x 2 matrix to see what kind of scenarios are produced when one, both, or neither of the solutions are implemented.

The matrix consisted of an X-axis that ranged from no weight bias training existing in family medicine education to weight bias training implemented in family medicine education. The Y- axis ranged from no existence of healthcare policies in regards to weight bias in family medicine to healthcare policies of such sorts being implemented. Forecasting possible future states using these ranges resulted in the following scenarios:

Collaboration Model

Scenario 1: Implemented weight bias policies but no weight bias curriculum

In this scenario, Public Health Ontario puts out policies that set fair and appropriate care standards for fat patients by family doctors. Doctors in family practices across Ontario have to follow basic standards such as diagnosing beyond weight, referring to necessary tests and specialists despite weight and following a behavior-oriented treatment model. However, in this scenario, medical education continues using the current curriculum with no additional training on weight bias.

Scenario 2: Implemented weight bias policies and implemented weight bias curriculum

This scenario represents the desired future for this issue. Not only does Public Health Ontario put out the policies described in Scenario 1, medical schools also introduce weight bias training in their curriculum for current students, and through continuing education for existing professionals.

Scenario 3: No weight bias policies or weight bias training in the curriculum

This scenario represents the current state of things, with neither initiative being implemented in family medicine practices and education.

Scenario 4: Implemented weight bias curriculum but no weight bias healthcare policies

This scenario is the opposite of Scenario 1. Medical schools in Ontario revamp their curriculum to include weight-bias training and offer courses through continuing studies, but there is no policy-level intervention to complement this initiative in professional settings.

Looking at the four scenarios, one can deduce that to effectively reduce weight bias in family medicine, both solution spaces – creating new policies and adding a weight bias curriculum – will need to be considered. In the next steps, an intervention model and an implementation roadmap will be proposed to reach the goal of reducing weight bias in Ontario healthcare.

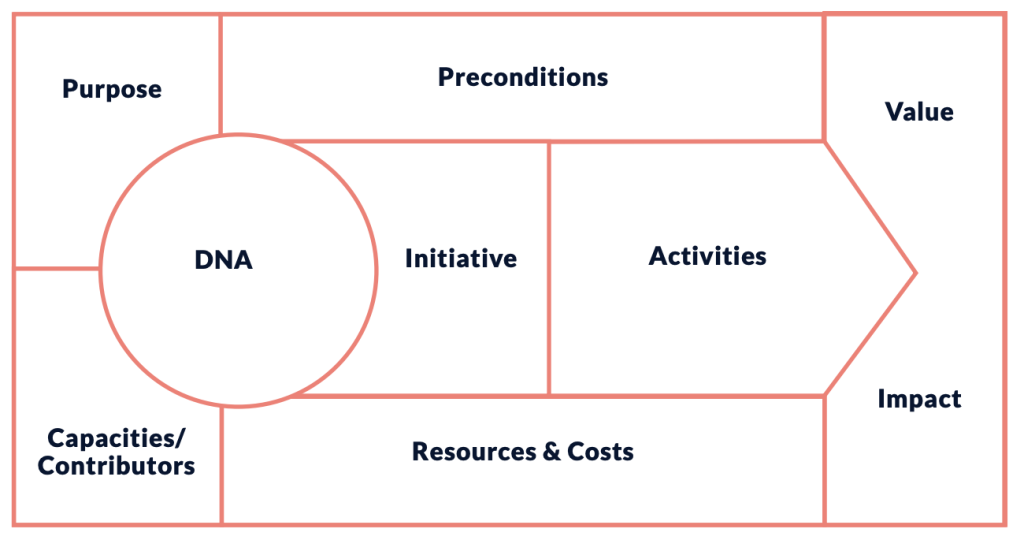

The model for change, also known as the intervention model, describes the DNA of change within a system; it contains the principles/activities that will enable change in the system (Systemic Design Toolkit, 2020). This step will combine the policy and curriculum solution spaces from the last step to create an intervention model that will seek to create change through governance and education. During Step 3 of this project, a key insight, which will be crucial for this new model, was discovered. This insight demonstrated a considerable disconnect between the scientific research side of weight bias and obesity and the social activism side. Both subsystems have the same goal. They both want to see better health and respect, proper treatment, and unbiased diagnoses of fat people in healthcare so that fat people can sustain their health and improve their livelihoods. Merging these two groups will form the backbone of this new strategy.

The key theme in this intervention model is collaboration. First, there is a collaboration of two different solution spaces: policy and curriculum. Second, there is the collaboration of different sub-systems – governance, education, and social activism – which is mandatory to make this initiative possible. Therefore, the best way to present this model is to draft it on the Collaboration Model Canvas from the Systemic Design Toolkit.

The Collaboration Model is similar to a Business Model Canvas (BMC). The BMC allows businesses to design, describe, invent, and pivot their business model by determining core structures such as key activities, resources, partners, financials, values, etc. (Osterwalder et al, 2010). The Collaboration Model uses similar segments to build an intervention model, but with a focus on collaborators working on the solution, their capacities, values, and resources (Collaboration Model, n.d.).

Collaboration Model

DNA – What key characteristics will inspire the collaboration?

Purpose – What is the main purpose of the collaboration?

Capacities – Who will contribute? With what capacities?

Initiative – What is the purpose of the joint initiative? What changes do you want to achieve? For whom? What are the short-term and long-term goals?

Activities – What are the key activities?

Value/Impact – What is the value created in the short-term and long-term? What is the value for the collaborating organizations and community? How will this be measured?

Preconditions – Are there any regulations, processes or attitudes that should change to make the initiative possible or more impactful?

Resources and Costs – What resources and finances are required? Where will they come from?

Collaboration Model: Reducing Weight Bias in Ontario Healthcare

DNA

The key characteristics of this strategy are embedded in system-wide collaboration with the partnership of scientific researchers and social activists. The strategy promotes policy and curriculum changes to reach compassion and respect between family doctors and fat patients.

Purpose

This collaborative strategy aims to bring holistic change so that not only does it make a difference now, but that change also sustains. Introducing policy changes will tackle weight bias in the existing family medicine system, but intervening in the medical education system will improve the issue for the future. Social activism will get the engine running, but science will need to fuel that engine to bring validity to the claims.

Contributors and their Capacities

This strategy’s main contributors are weight bias researchers, obesity researchers, fat activists and influencers, health policy-makers, the Ontario government, and medical school faculties. Weight bias researchers will need to continue providing studies on weight stigma. Obesity researchers will need to measure the different outcomes of reducing weight bias in healthcare, for example, whether proper care reduces the rate of mortality for fat patients. Fat liberation activists will be the driving force of the movement, bringing awareness and the attention of decision-makers to the issue. Health policymakers will need to investigate the problem and work through the policy development process to implement new policies. The Ontario government will need to support the policy-makers and ensure sufficient funding is available for family practices to allay other issues in the system. Lastly, medical school faculties will need to work within their institutions to convince the authorities to make curriculum changes.

Initiatives

The initiative encompasses three main goals, reducing weight bias in family clinics, increasing respect and empathy between the family doctors and fat patients, and working towards a behavior-focused care model rather than outcomes. These will advance and improve healthcare for all fat patients. The short-term goals are to gain momentum and support for policy and curriculum changes and see an increase in the number of fat-positive clinics and family doctors. The long-term goal is to see the policy changes enacted and weight bias curriculum added, and a province-wide decrease of weight bias in family medicine.

Activities

The key activities are divided into two streams – education and policy. Both streams begin with organizing fat activists, obesity and weight bias researchers and family doctors who already support the cause. The next step is to collaborate with influential stakeholders in each stream to draft and present proposals that build a case for the problem. From there on, continuous efforts are required from activists, researchers, and partners to build a curriculum and place the issue on the table of Public Health Ontario’s policy-makers. A more detailed glance at the activities and future steps will be provided in Step 7’s roadmap.

Value Created/ Measuring Impact

The strategy produces incredible value for fat patients by creating judgment-free health experiences and better physical and mental health due to respectful healthcare. It also creates value for the healthcare community, whose worry is the ‘obesity epidemic’ and its effects. Evidence abounds that health can be improved through physical activity, maintaining proper nutrition, and reducing stress, even in the absence of weight loss (Mann et al, 2015). Therefore, if family doctors in the province adopt the behavior-centric model of treating their fat patients, the negative results from obesity can be mitigated. In fact, a non-biased healthcare approach towards fat people will eliminate their hesitancy to access preventive care. More preventive care could further reduce fat people’s health problems, thus lengthening their lives and possibly reducing the morbidity levels attached to obesity. There are a few possible ways to measure the impact of this strategy long term. Obesity rates, depression rates in fat people, and eating disorder rates would be good indicators of change. Expansion of the strategy federally and globally would prove its ability to reduce weight bias.

Preconditions

Certain attitudes will need to change to implement this model. Incredible perseverance and continued efforts are required consistently throughout the process. Once the ball is rolling, contributors will need to move from the awareness stage to the action phase without stopping awareness. An open-minded and positive attitude is necessary because ideas and efforts might get shut down, considering how accepting weight bias is in this society. Ultimately, negative attitudes about fat people and being fat will need to be kept in check, as they creep up very quickly.

Resources and Costs

The strategy will require a lot of time and energy from activists and researchers. It needs the support of organizations with financial capability already working towards similar issues. Free, earned, and shared media is critical to gain momentum as well as GoFundMe campaigns and other grants. In the later stages, the government will need to allocate funding to implement the health policies, and universities will need to budget expenditures on running weight bias training courses. This comprehensive education and governance strategy driven by the partnership of activism and research sets up a strong foundation toward decreasing weight bias in Ontario family clinics. In the next step, a roadmap will be introduced to demonstrate the implementation procedure.

Step 7 of the Systemic Design toolkit involves creating a transition plan to implement the new intervention strategy. This step utilizes the Roadmap for Transition tool, which plans the implementation of the interventions so that change occurs by design. It is used to map the transition toward the desired goal by planning and growing the intervention model in time and space (Systemic Design Toolkit, 2020).

Media Attributions

- Plus size people in room © AllGo - An App For Plus Size People via. Unsplash is licensed under a CC0 (Creative Commons Zero) license

- Woman in classroom © AllGo - An App For Plus Size People via. Unsplash is licensed under a CC0 (Creative Commons Zero) license

- 2×2 matrix © "Dismantling Weight Bias Towards Overweight Patients in Ontario Healthcare" by Ireena Haque is licensed under a CC BY-NC-SA (Attribution NonCommercial ShareAlike) license

- Collaboration Model © "Dismantling Weight Bias Towards Overweight Patients in Ontario Healthcare" by Ireena Haque is licensed under a CC BY-NC-SA (Attribution NonCommercial ShareAlike) license