Writing has a trajectory. You begin with an assignment or a desire to write, and you end with a final product. The in-between parts vary substantially from person to person and even task to task, which means that you may have multiple processes. But the overall trajectory for writing tasks is similar enough that we can talk about it.

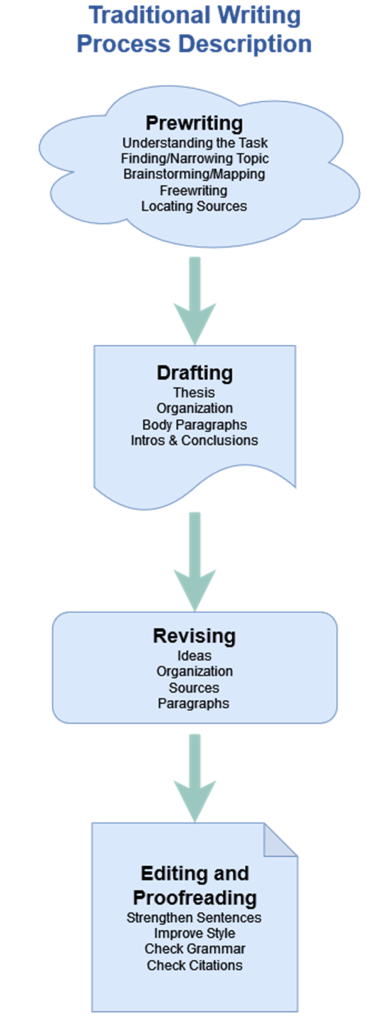

You may have seen diagrams of the process that look something like the one on the right. It’s a bit over simplified, but in general, the writing process has frequently been described in relatively linear terms as a movement from prewriting to drafting to revising to editing and proofreading.

You may also have heard that this process is recursive. This means that writers frequently go back to earlier stages when, for example, they discover a new idea that needs additional prewriting and drafting work before it can be incorporated in a revision. Sometimes such recursion will appear as arrows linking the stages in reverse.

Some models will include feedback from readers, usually in between the drafting and revising stage. Feedback at this stage usually helps writers refine their drafts and produce better revisions.

Audio Explanation of the Traditional Writing Process Diagram

Transcript of Audio for the Traditional Writing Process Description

The traditional writing process is usually drawn as a series of four or five stages, usually represented linearly.

The first stage is prewriting, and this is where the writer determines the task, narrows it down, identifies their topic, does brainstorming, free writing, locating sources, those kinds of things. The second stage is usually drafting, and this is the stage where text is actually produced, where the author puts together their thesis, they write body paragraphs, they produce an introduction and conclusion, and put it all together in a draft. The third stage is revising, and this is where the writer takes the ideas that they have in their draft and reconsiders them. True revising is looking at the ideas, the organization, the sources. How are you putting together those ideas? Will it make sense to somebody outside of yourself? The fourth stage is editing and proofreading, and this is where a writer goes in to strengthen their sentences and improve their style. This is also where grammar checking will happen and proofreading as well happens in this stage. Sometimes that’s treated as a separate item.

You will frequently hear the word recursive around this process model and that is intended to indicate that, at any given point, the writer may go back to what is considered an earlier phase and need to do some work. So, for example, in the midst of revising, a writer might discover that they need another source, and so they will go back to the prewriting phase to identify the source and add it in to their work.

This image presents a relatively neat process, and it implies that if you just follow the steps, you’ll come out with a finished project. But the process is rarely this neat—or even neat at all.

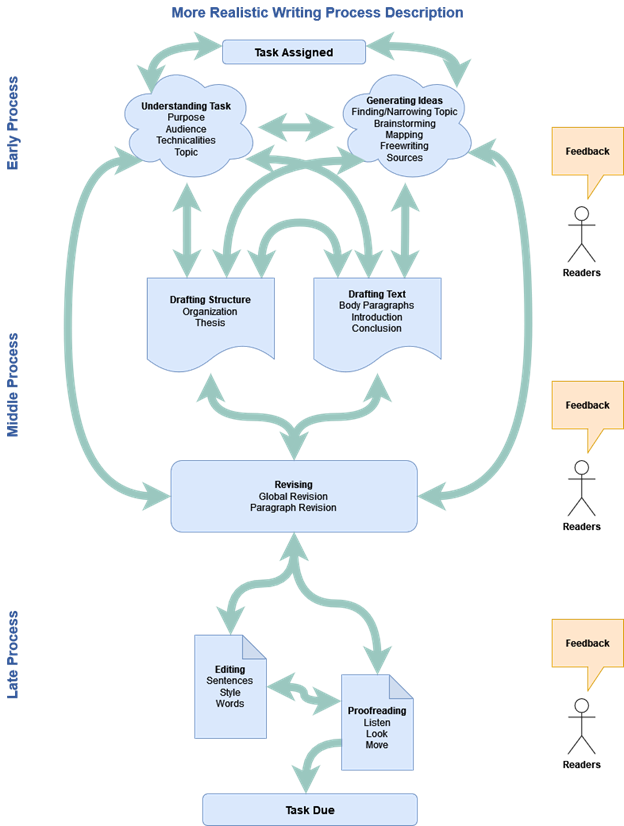

Compare this with the model depicted in the image below. The trajectory stays the same (assignment to final version), but there can be a lot of variation as we move through the “stages” in between:

- Some writers like to get their ideas out on paper or screen quickly, folding prewriting into writing and revising.

- Some writers like to think long and hard about what they are going to write before ever touching the keyboard.

- Some writers like to write the perfect introduction before they do anything else.

- Some like to skip the introduction until the end of the first draft.

- Some want to read everything they are going to write about first; some want to read as they go.

None of these approaches is “right” or “wrong.”

Audio Explanation of the More Realistic Writing Process Diagram

Transcript of Audio for the Realistic Writing Process Description

I have developed a model of the writing process that I consider to be more realistic than the traditional model I describe earlier in this chapter. This model bears some resemblance to that traditional model, but I believe it does a better job acknowledging the complexity of any writing task.

I have divided the process into three phases: early, middle, and late.

In the early phase, the writer either identifies a writing task or is given such a task, and they work to understand that task – determining their audience and purpose, as well as their topic. They also start generating ideas, whether through brainstorming or locating sources. Early phase work may also involve drafting, including developing a working thesis statement or starting to shape ideas into paragraphs.

My model has no clear dividing line between the early and middle phases, but at some point, a writer is producing text more than gathering ideas. At this point, a writer might, for example, concentrate on fully developing paragraphs to explain their ideas and drafting an introduction and conclusion.

Revision work bridges the middle and late process in this model. Revision is the phase where a writer is more concerned with reworking ideas than generating new ones, and where they are likely to focus more fully on making their ideas clear for a reader.

Editing and proofreading are decidedly late phase work because they happen as the deadline approaches, whether the deadline is imposed by an instructor, by a boss, or by themselves. This is where a writer turns to strengthening their sentences more than their ideas, including focusing on their style and word choice, as well as proofreading their work to eliminate error.

There are two aspects to the model I’ve developed that differ substantially from the more linear, traditional model described earlier in this chapter. The first is the role of feedback. Often, feedback is left out of descriptions of the traditional model, though when it appears, it usually appears in the late-middle or late phases. This model includes feedback at any point in the process, even early as the writer is understanding the task and gathering ideas. Some kinds of feedback work better on a draft piece of text, but not all of them, and sometimes a writer needs input early.

The second difference is the integration of recursion. Throughout the model, arrows point back and forth, connecting various elements. The arrows are most interconnected early in the process, when, for example, a writer may realize as they are organizing their ideas that they have not yet explained a key point, one that requires a return to some of their sources. Part of the intent of all of the arrows in the diagram is to indicate that there is no one path to creating a piece of writing.

At the same time, there are relatively few arrows connecting the late-process work to earlier phases. As a deadline approaches, a writer really must turn to shaping the text they have generated, which means focusing on editing and proofreading, perhaps with some revision to ideas.

I prefer this model because I believe it does a better job than the traditional model in acknowledging the complexity inherent in writing tasks.

This text describes a writing process trajectory as represented in this image. At each “stage,” I present a range of techniques and strategies for that kind of work.

As you use this text, try focusing more on what you are trying to accomplish by writing instead of the order of the stages. While it is important to keep making progress on an assignment, it is actually more important to recognize, for example, whether you are ready to revise or whether you need to go back to the assignment itself to focus on your purpose.

With each of the strategies I suggest, your mileage may vary. My recommendation is that you try them with an open mind, particularly the ones that your instructor recommends. Be ready to consider approaches that have not worked for you in the past or that you have never tried. You might find something new that will help you write more successfully.

Procrastination

Economy vs. Copia

Before we get too far into “the process,” I want to think about general attitudes and habits toward writing.

Let’s start with the “I hate writing” attitude that quite a few students have expressed to me over the years. If you hate writing now, I’m not going to promise that you’ll come out on the other side of this text or this course loving writing—or even necessarily hating it less. But I have designed this book to help you feel more comfortable with writing because you’ll know more about how to succeed in the writing tasks that you’ll be given in college.

Even if you don’t hate writing, you may have developed an attitude or habit around writing that is particularly harmful: economy in writing. Students are very busy people. Technically, if you are taking a full load of courses, you should be working more than forty hours a week on your academics. As a result, students tend to think that they should only write only to the minimum word count and then stop.

More than 40 hours?

According to federal regulation 34 CFR 600.2, a credit hour is defined as one hour of instruction plus two hours of work outside of instruction (Code). While there are adjustments and exceptions (for courses like labs), in short, this means that each credit hour requires three hours of work from you—generally one in the classroom with the instructor and two outside on your own.

I know this is a writing textbook, but let’s do a little math. If you are taking a 3-credit course, then, you should be putting in nine hours, and if you are taking a 4-credit course, you should be putting in twelve.

If you are taking five 3-credit courses (a typical full load in many institutions), you’re expected to put in 45 hours between class and preparation time.

If you are taking four 4-credit courses (again, a typical full load), you’re expected to put in 48 hours.

So, yes, really. More than 40 hours.

Students who write economically rarely produce more than a first draft. Remember what I said about one-night wonders? Those first drafts might be good enough, but they won’t be your best work. Not everything in our first drafts is really that good. In the process of writing this book, for example, I have probably thrown out nearly as many words as I have written—if not more.

In an economic approach, you end up turning in subpar work, keeping words you have produced just because you have produced them.

In copia (from Latin, meaning “abundance”), writers write a lot. They produce words freely, writing more than the assignment requires so that they can find the best 900 words in the 1500 that they have produced. When writers—including students—take this approach, we are able to produce better writing because we have more to choose from.

One key thing to know here is that copia doesn’t really take more time than economy. If you have ever written economically, think about how long you stared at a blank screen or piece of paper, agonizing over what to say and how to say it “right.” You probably didn’t save any time over jumping in and writing whatever you were thinking, even if those thoughts weren’t very coherent and didn’t quite fit into the project at hand.

If you had jumped in and started writing, you might have pushed your thinking into better territory faster, and some of what you wrote might have actually been good enough for your final version, even if you ended up throwing out a bunch of words.

If you have been an economic writer in the past, this might be a good moment for change.

Key Points: Thinking about Writing Process

- There is no single writing process.

- Your process is likely to be complex, but that’s not a problem.

- You will never produce your best writing at the last minute.

- If you allow yourself to produce more words than you need for the assignment, you will have choices.

In writing, the understanding that the process tends to loop back so that while a writer moves through stages, they also frequently come back to earlier stages to improve their writing.

An approach to writing in which a person only does as much writing as is required to complete the task and the person includes all of their writing in the final product. This approach stands in contrast to copia.

An approach to writing in which the writer generates a lot of writing and then selects the best, given their purpose and audience. This word is written in italics because it's a foreign word. This approach stands in contrast to economy.