Different Types of Respiratory Systems

Section Goals

By the end of this section, you will be able to do the following:

- Discuss the respiratory processes used by animals without lungs

- Identify structures in mammalian respiratory systems and their functions

- Describe the passage of air from the outside environment to the lungs

The primary function of the respiratory system is to deliver oxygen to the cells of the body’s tissues and remove carbon dioxide, a cell waste product.

All aerobic organisms require oxygen to carry out their metabolic functions. Along the evolutionary tree, different organisms have devised different means of obtaining oxygen from the surrounding atmosphere. The environment in which the animal lives greatly determines how an animal respires. The complexity of the respiratory system is correlated with the size of the organism. As animal size increases, diffusion distances increase and the ratio of surface area to volume drops. In unicellular organisms, diffusion across the cell membrane is sufficient for supplying oxygen to the cell (Figure 1).

Diffusion is a slow, passive transport process. In order for diffusion to be a feasible means of providing oxygen to the cell, the rate of oxygen uptake must match the rate of diffusion across the membrane. In other words, if the cell were very large or thick, diffusion would not be able to provide oxygen quickly enough to the inside of the cell. Therefore, dependence on diffusion as a means of obtaining oxygen and removing carbon dioxide remains feasible only for small organisms or those with highly-flattened bodies, such as many flatworms (Platyhelminthes). Larger organisms had to evolve specialized respiratory tissues, such as gills, lungs, and respiratory passages accompanied by complex circulatory systems, to transport oxygen throughout their entire body.

Direct Diffusion

For small multicellular organisms, diffusion across the outer membrane is sufficient to meet their oxygen needs. Gas exchange by direct diffusion across surface membranes is efficient for organisms less than 1 mm in diameter. In simple organisms, such as cnidarians and flatworms, every cell in the body is close to the external environment. Their cells are kept moist and gases diffuse quickly via direct diffusion. Flatworms are small, literally “flat” worms, which “breathe” through diffusion across the outer membrane (Figure 2).

The flat shape of these organisms increases the surface area for diffusion, ensuring that each cell within the body is close to the outer membrane surface and has access to oxygen. If the flatworm had a cylindrical body, then the cells in the center would not be able to get oxygen.

Skin and Gills

Earthworms and amphibians use their skin (integument) as a respiratory organ. A dense network of capillaries lies just below the skin and facilitates gas exchange between the external environment and the circulatory system. The respiratory surface must be kept moist in order for the gases to dissolve and diffuse across cell membranes.

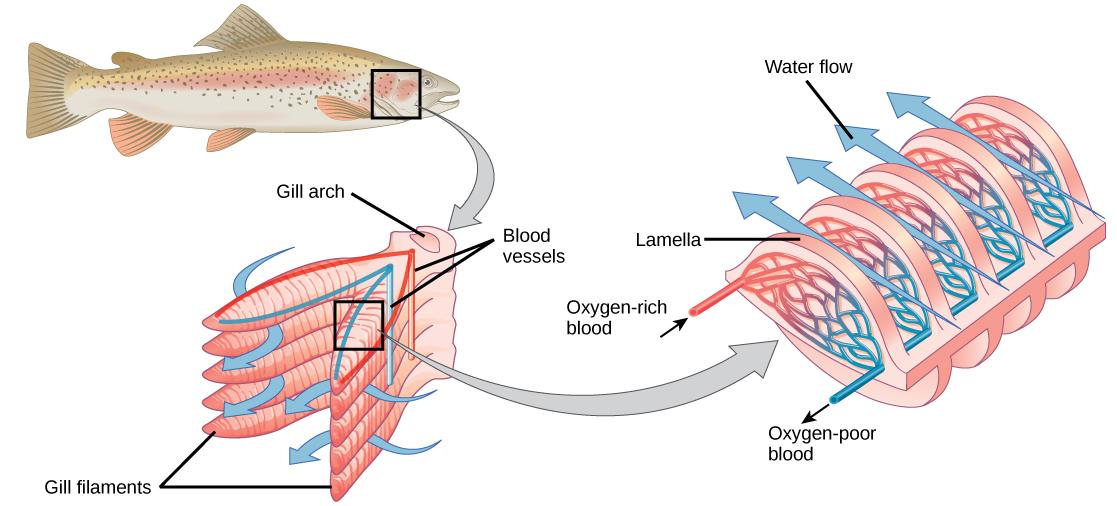

Organisms that live in water need to obtain oxygen from the water. Oxygen dissolves in water but at a lower concentration than in the atmosphere. The atmosphere has roughly 21 percent oxygen. In water, the oxygen concentration is much smaller than that. Fish and many other aquatic organisms have evolved gills to take up the dissolved oxygen from water (Figure 3).

Gills are thin tissue filaments that are highly branched and folded. When water passes over the gills, the dissolved oxygen in water rapidly diffuses across the gills into the bloodstream. The circulatory system can then carry the oxygenated blood to the other parts of the body. In animals that contain coelomic fluid instead of blood, oxygen diffuses across the gill surfaces into the coelomic fluid. Gills are found in mollusks, annelids, and crustaceans.

The folded surfaces of the gills provide a large surface area to ensure that the fish gets sufficient oxygen. Diffusion is a process in which material travels from regions of high concentration to low concentration until equilibrium is reached. In this case, blood with a low concentration of oxygen molecules circulates through the gills. The concentration of oxygen molecules in water is higher than the concentration of oxygen molecules in gills. As a result, oxygen molecules diffuse from water (high concentration) to blood (low concentration), as shown in Figure 4. Similarly, carbon dioxide molecules in the blood diffuse from the blood (high concentration) to water (low concentration).

Tracheal Systems

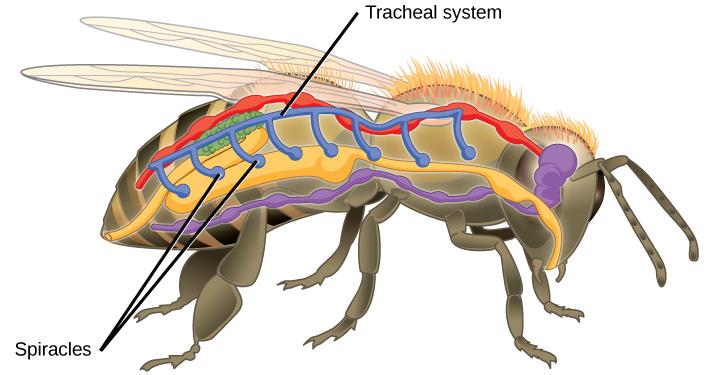

Insect respiration is independent of its circulatory system; therefore, the blood does not play a direct role in oxygen transport. Insects have a highly specialized type of respiratory system called the tracheal system, which consists of a network of small tubes that carries oxygen to the entire body. The tracheal system is the most direct and efficient respiratory system in active animals. The tubes in the tracheal system are made of a polymeric material called chitin.

Insect bodies have openings, called spiracles, along the thorax and abdomen. These openings connect to the tubular network, allowing oxygen to pass into the body (Figure 5) and regulating the diffusion of CO2 and water vapor. Air enters and leaves the tracheal system through the spiracles. Some insects can ventilate the tracheal system with body movements.

Did I Get It?

Mammalian Respiratory Systems

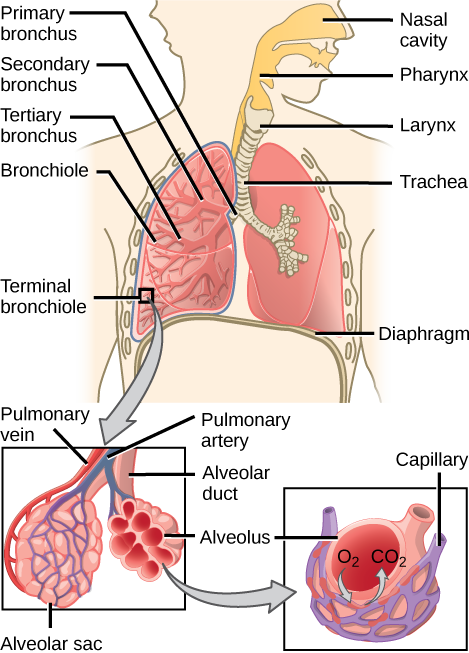

In mammals, pulmonary ventilation occurs via inhalation (breathing). During inhalation, air enters the body through the nasal cavity located just inside the nose (Figure 6). As air passes through the nasal cavity, the air is warmed to body temperature and humidified. The respiratory tract is coated with mucus to seal the tissues from direct contact with air. Mucus is high in water. As air crosses these surfaces of the mucous membranes, it picks up water. These processes help equilibrate the air to the body conditions, reducing any damage that cold, dry air can cause. Particulate matter that is floating in the air is removed in the nasal passages via mucus and cilia. The processes of warming, humidifying, and removing particles are important protective mechanisms that prevent damage to the trachea and lungs. Thus, inhalation serves several purposes in addition to bringing oxygen into the respiratory system.

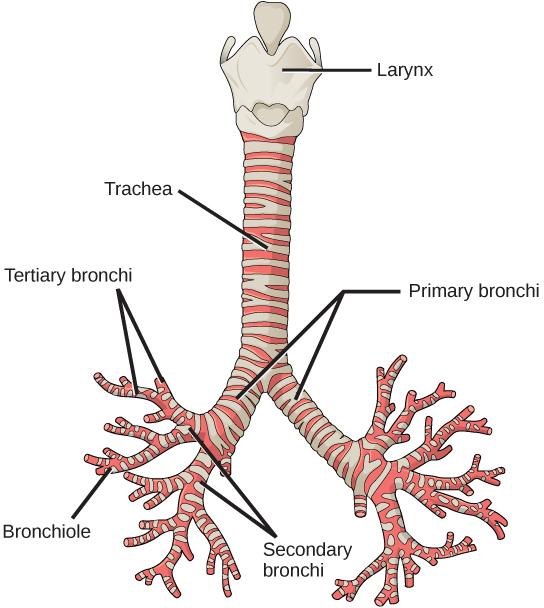

From the nasal cavity, air passes through the pharynx (throat) and the larynx (voice box), as it makes its way to the trachea (Figure 6). The main function of the trachea is to funnel the inhaled air to the lungs and the exhaled air back out of the body. The human trachea is a cylinder about 10 to 12 cm long and 2 cm in diameter that sits in front of the esophagus and extends from the larynx into the chest cavity where it divides into the two primary bronchi at the midthorax. It is made of incomplete rings of hyaline cartilage and smooth muscle (Figure 7).

The trachea is lined with mucus-producing goblet cells and ciliated epithelia. The cilia propel foreign particles trapped in the mucus toward the pharynx. The cartilage provides strength and support to the trachea to keep the passage open. The smooth muscle can contract, decreasing the trachea’s diameter, which causes expired air to rush upwards from the lungs at a great force. The forced exhalation helps expel mucus when we cough. Smooth muscle can contract or relax, depending on stimuli from the external environment or the body’s nervous system.

Lungs: Bronchi and Alveoli

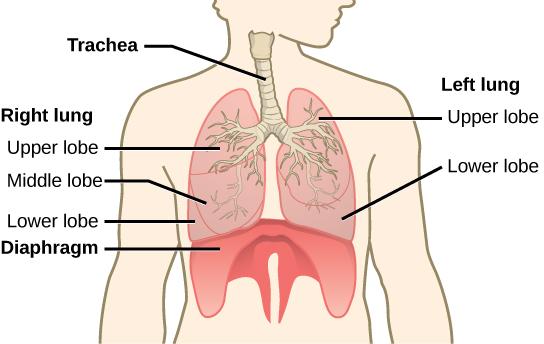

The end of the trachea bifurcates (divides) to the right and left lungs. The lungs are not identical. The right lung is larger and contains three lobes, whereas the smaller left lung contains two lobes (Figure 8). The muscular diaphragm, which facilitates breathing, is inferior (below) to the lungs and marks the end of the thoracic cavity.

In the lungs, air is diverted into smaller and smaller passages, or bronchi. Air enters the lungs through the two primary (main) bronchi (singular: bronchus). Each bronchus divides into secondary bronchi, then into tertiary bronchi, which in turn divide, creating smaller and smaller diameter bronchioles as they split and spread through the lung. Like the trachea, the bronchi are made of cartilage and smooth muscle. At the bronchioles, the cartilage is replaced with elastic fibers. Bronchi are innervated by nerves of both the parasympathetic and sympathetic nervous systems that control muscle contraction (parasympathetic) or relaxation (sympathetic) in the bronchi and bronchioles, depending on the nervous system’s cues. In humans, bronchioles with a diameter smaller than 0.5 mm are the respiratory bronchioles. They lack cartilage and therefore rely on inhaled air to support their shape. As the passageways decrease in diameter, the relative amount of smooth muscle increases.

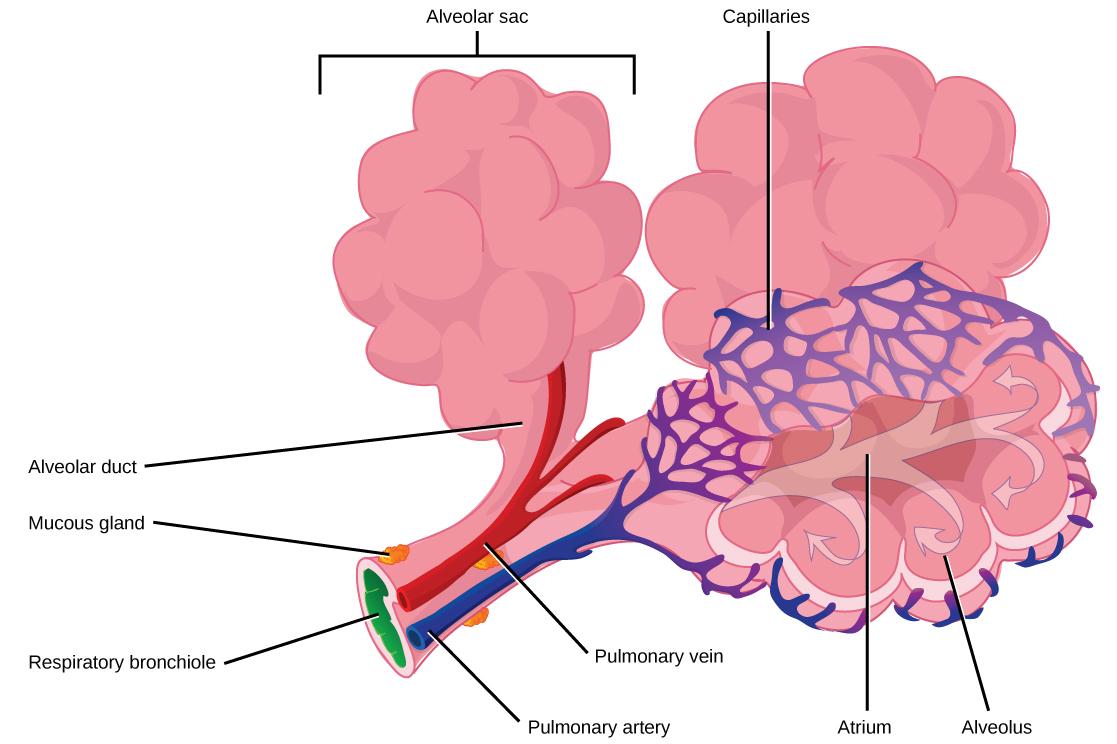

The terminal bronchioles subdivide into microscopic branches called respiratory bronchioles. The respiratory bronchioles subdivide into several alveolar ducts. Numerous alveoli and alveolar sacs surround the alveolar ducts. The alveolar sacs resemble bunches of grapes tethered to the end of the bronchioles (Figure 9).

In the acinar region, the alveolar ducts are attached to the end of each bronchiole. At the end of each duct are approximately 100 alveolar sacs, each containing 20 to 30 alveoli that are 200 to 300 microns in diameter. Gas exchange occurs only in alveoli. Alveoli are made of thin-walled parenchymal cells, typically one-cell thick, that look like tiny bubbles within the sacs. Alveoli are in direct contact with capillaries (one-cell thick) of the circulatory system. Such intimate contact ensures that oxygen will diffuse from alveoli into the blood and be distributed to the cells of the body. In addition, the carbon dioxide that was produced by cells as a waste product will diffuse from the blood into alveoli to be exhaled. The anatomical arrangement of capillaries and alveoli emphasizes the structural and functional relationship of the respiratory and circulatory systems. Because there are so many alveoli (~300 million per lung) within each alveolar sac and so many sacs at the end of each alveolar duct, the lungs have a sponge-like consistency. This organization produces a very large surface area that is available for gas exchange. The surface area of alveoli in the lungs is approximately 75 m2. This large surface area, combined with the thin-walled nature of the alveolar parenchymal cells, allows gases to easily diffuse across the cells.

In the next video, watch as educator Sal Khan draws and explains the journey of our breath as it travels into the body, through the lungs, and ultimately delivers oxygen to our bloodstream.

Did I Get It?

CC Licensed Content, Shared Previously, Included in An Introduction to Animal Physiology

- Biology 2e. Authors: Mary Ann Clark, Matthew Douglas and Jung Choi. Provided by: OpenStax CNX. Located at: Biology 2e. License: CC BY: Attribution 4.0.

- Biology for Majors II. Authors: Shelly Carter and Monisha Scott. Provided by: Lumen Learning. Located at: Biology for Majors II | Simple Book Production. License: CC BY: Attribution 4.0.

- The lungs and pulmonary system. Provided by: Khan Academy. Located at: The lungs and pulmonary system (video) | Circulatory and pulmonary systems | Khan Academy. License: CC BY-NC-SA 4.0